Forgotten Scandal: Omene, the Suicide Club, and Celebrity Culture in 19th-Century America

«The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection of Printed Ephemera in the Department of Drawings and Prints contains 13 portraits of a woman named Omene. Now entirely forgotten in the history of dance and entertainment, Omene achieved an incredible level of celebrity in the national press of the 1890s as an early practitioner of belly dancing on the American stage. She was best known, however, for inciting scandal.»

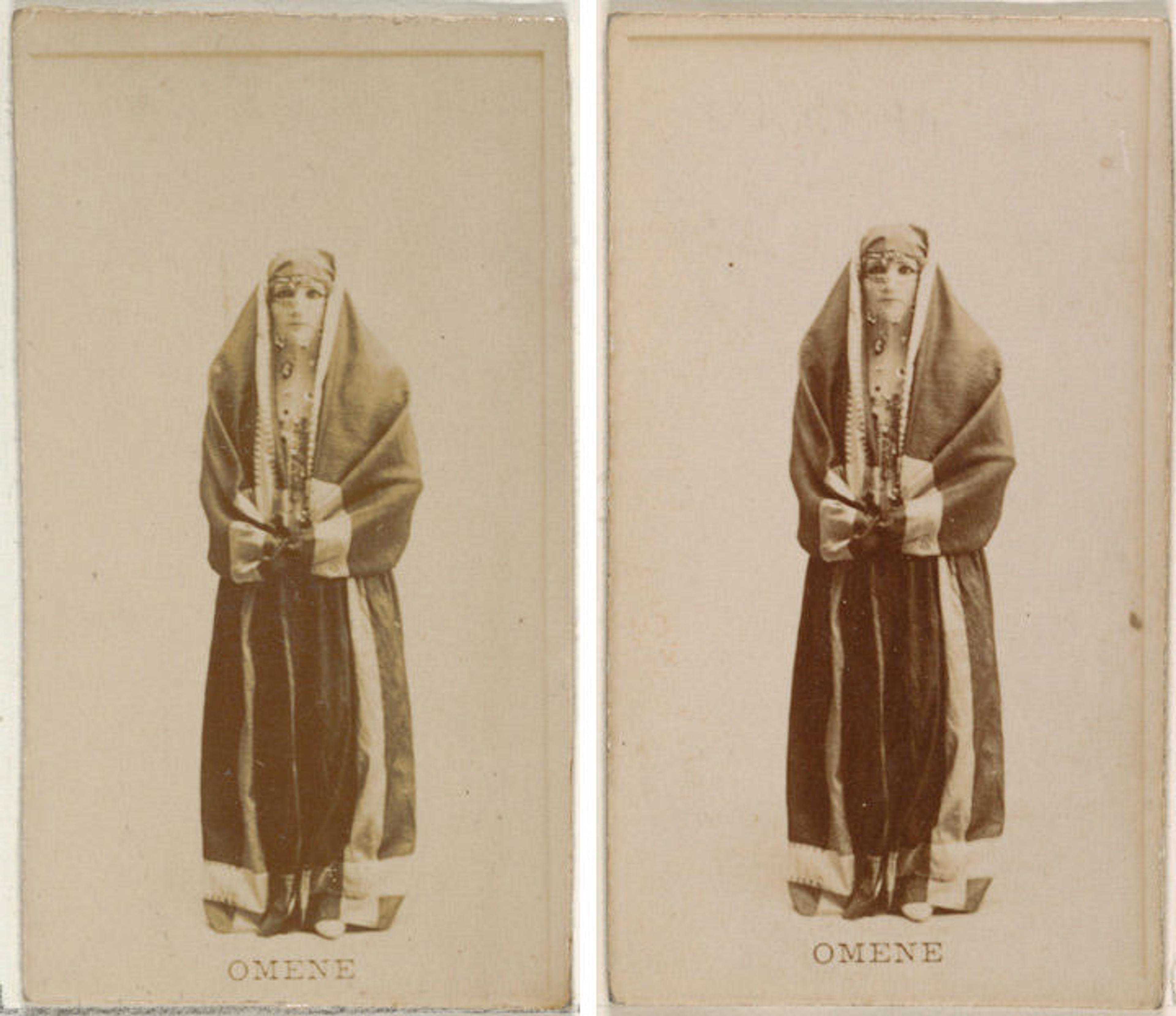

Left: Fig. 1. Issued by Kinney Brothers (American). Omene, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1890. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 1/2 x 1 7/16 in. (6.4 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.220.245.1402)

The 13 tobacco cards in the Burdick Collection that bear Omene's portrait stand as evidence of the proliferation and commodification of celebrity in late 19th-century America. Her portrait was highly sought after, to be purchased, consumed, and collected by a rapt national audience.

Belly dancing, or the danse du ventre, did not reach theaters in America, for the most part, until the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. From its introduction, audiences considered the dance scandalous because of the dancers' gyrating hips and corset-less costumes. Too shocking for upscale theater audiences, burlesque shows and carnivals quickly became the dance's showcase. Belly dancing drew large numbers of gawkers seeking the notorious dance moves and costumes. The danse du ventre soon evolved into the "hoochie coochie" and "couchee couchee" in Victorian-era America.

Right: Fig. 2. Issued by Allen & Ginter (American, Richmond, Virginia). Omene, from the Actors and Actresses series (N45, Type 8) for Virginia Brights Cigarettes, ca. 1888. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 5/8 x 1 1/2 in. (6.6 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.203.45.1375)

Omene's arrival as a belly dancer on the American stage, in 1889, predated the Chicago World's Fair by four years. She came to New York in the company of a Japanese illusionist named Yank-Hoe, performing for their first American audience at the Union Square Theatre that August. Interviewed by the National Police Gazette, Omene distinguished her traditional dance from the performances of the burlesque pretenders: "I saw the abortion which the dancers of the Midway presented to the public, and it filled me with heartache and loathing . . . Their dance was but a low-bred copy, designed to excite coarse men" (May 5, 1894).

Omene claimed the following story of origin. She was born in Istanbul, the daughter of a Turkish army officer father and a mother who was a professional dancer. Beginning at the age of eight, Omene learned the art of belly dancing from her mother, but was married off to an English army officer at the age of twelve. The unnamed officer took Omene to Egypt, and they soon had a daughter, Nadine. After the officer abandoned Omene and Nadine, the two moved to London, and Omene began performing traditional Turkish dance for English audiences. While in London, Omene fell in love with Yank-Hoe, who brought her and Nadine to America.

Omene's love affairs became popular topics in the national news. Newspapers duly reported her escapades of love gained and lost, and Omene became better known for melodrama than dancing; one besotted newspaper reporter even committed suicide. Omene and Yank-Hoe's relationship was highly combustible. In 1892, Omene reported Yank-Hoe to the police for stealing her costumes and clothing in order to keep her from leaving him. As a result, Yank-Hoe was imprisoned for a short time and forced to return the items to Omene. The couple reunited soon after.

One year later, Omene became entangled with the Marquis Edmundo de Olivieri of Hoboken, New Jersey. When the affair soured, the marquis accused Omene of stealing valuable objects including diamond jewelry and a snuff box set with precious stones. Omene rebuked the accusation, stating that the marquis had given Omene the objects as gifts after asking her to marry him.

Left: Fig. 3. Issued by Kinney Brothers (American). Omene, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1890. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 1/2 x 1 7/16 in. (6.4 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.220.245.1401)

Omene's most notorious scandal had to do with a press club in Chicago called the Whitechapel Club. As much a secret society as press club, the Whitechapel Club—also known as the Suicide Club—was founded by a group of Chicago newspapermen in 1889. The club was named after the area of London where Jack the Ripper prowled for victims, and the legendary serial killer was named (absentee) president.

The club's quarters were a testament to the grotesque. The walls were decorated with pistols and knives that had been used for murder, human skeletons were hung above the central table, and skulls were fitted as shades for the gas-lighting fixtures. The bloody slipper of a Chinese merchant killed by a streetcar was nailed to a wall, donated by the San Francisco police force. Goblets were made from skulls of local prostitutes.

Although the Suicide Club engaged in traditions and decorations both morbid and grotesque, a wide variety of celebrities sought entrance as honored guests. Future presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William McKinley both spent time at the club. Women were strictly forbidden—in fact, Omene was the only female to enter in the club's history. Already a favorite subject of reporters, Omene was asked to dine with the members and perform a dance. Although sworn to secrecy, the savvy self-promoter readily brought her story to the San Francisco Morning Call (June 10, 1893) and eagerly revealed the secrets she discovered in the inner sanctum.

Omene described the furniture built from coffins as well as the instruments of murder mounted on the walls. She was asked to perform on top of a stage created from a coffin and, in keeping with the theme and audience enthusiasm, danced with a skull and bones in her hands. Omene was already famous by the time she visited the Whitechapel Club, but her "Coffin Dance"—discussed in newspapers across the country—made her infamous.

Readers had no idea what Omene actually looked like because the coverage predated published photographs in newspapers. The primary vehicle by which audiences were able to see her image was through collectible tobacco-card inserts. Tobacco cards, inserted into packs of cigarettes and packages of loose-leaf tobacco, were intended to be collected and traded much like baseball cards.

Left: Fig. 4. Issued by Allen & Ginter (American, Richmond, Virginia). Omene, from the Actors and Actresses series (N45, Type 8) for Virginia Brights Cigarettes, ca. 1888. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 5/8 x 1 1/2 in. (6.6 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.203.45.1514). Right: Fig. 5. Issued by Kinney Brothers (American). Omene, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1890. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 1/2 x 1 7/16 in. (6.4 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.220.245.1406)

Tobacco cards constituted an organic outgrowth of a photographic fad called "cartomania" or "cardomania." Celebrity studio portraits were mass-produced and sold in order to confirm and bestow celebrity on a national scale. Hundreds of millions of cabinet card and carte-de-visite studio portraits depicting politicians, actors, authors, artists, and preachers were published, distributed, and collected from the 1870s through the 1890s.

Collectible tobacco insert cards displaying entertainers' portraits constituted a natural outgrowth of these widely distributed celebrity-card photographs. Apply a tobacco brand name onto the back of the image, and the photographic portrait transformed into an advertisement—the next logical step in perpetuating and solidifying celebrity status.

The Met's Burdick Collection includes over 6,000 tobacco insert cards from the late 1800s that depict theater performers of various levels of celebrity and notoriety. Two companies issued the 13 portraits of Omene in the collection as part of two larger series: Allen & Ginter produced four portraits in 1890 to promote their Virginia Brights Cigarettes; and Kinney Brothers issued nine portraits in the same year to advertise their Sweet Caporal Cigarettes.

What becomes immediately clear is that the two tobacco companies procured their imagery from the same sources. All four portraits of Omene published by Allen & Ginter were also duplicated by Kinney Brothers. Although the versos of the cards display differing advertisements, the presentation of Omene's portrait is exactly the same on each company's card, as seen in figures 4 and 5 above.

Right: Fig. 6. Issued by Kinney Brothers (American). Omene, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1890. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 2 1/2 x 1 7/16 in. (6.4 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.220.245.1408)

Considering that this portrait is the first public glimpse of the infamous dancer, Omene made a number of deliberate choices in cementing and propelling her celebrity persona. She dressed modestly to an extreme (fig. 6), the antithesis of her popular portrayal as a woman notorious for baring skin and not wearing a corset. Omene kept her hands and hair masked beneath a hooded cloak, and a veil obscured her face. Her heavily charcoaled eyes thus become the instant focus of the frame. Omene chose to emphasize her foreignness to the American audience, underscoring the mystery of her Eastern roots. In this manner, Omene demanded attention and yet contradicted the popular newspaper portrayals of her skin-baring performances.

Whereas Allen & Ginter published four quite disparate portraits of Omene—dancing as well as formal portraits in both traditional Turkish and modern American clothing—Kinney Brothers published multiple poses from these same portrait sittings. For example, Allen & Ginter published one image of Omene dancing (fig. 2). Kinney Brothers published this same image alongside others from the same studio sitting, creating not only more of a story line within the series but also a more compelling motive to collect the whole series by purchasing packs of cigarettes.

The series of Omene dancing lies in stark contrast to her more modest portrait session seen in figure 4, and features Omene dressed in her revealing stage costume. Rather than displaying traditional dance poses, Omene clowns on the empty stage, balancing a fan on her head (fig. 3), bowing (fig. 1), and, finally, lounging seductively on cushions placed on the studio floor (fig. 7). Here Omene displays a range of her coy and seductive powers that initially led the newspapermen, in great numbers, to seek her interviews.

Fig. 7. Issued by Kinney Brothers (American). Omene, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1890. Albumen photograph; Sheet: 1 7/16 x 2 1/2 in. (3.7 x 6.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.220.245.1409)

Omene was able to construct a popular and well-known mythology within American culture of the 1890s. She set herself above the "hoochie coochie" dancers with her Turkish roots, dancing pedigree, and ability to create and disseminate scandal and attention through the newspapers. But how much of this mythology was true? How much of Omene's celebrity character was a creation for self-promotion?

Two police reports belie Omene's constructed identity. The first incident, reported in the Salt Lake Herald in 1891, cites a Madge Hargreaves, known as Omene, accusing Yank-Hoe, her legal husband, of stealing her performance costumes during a lovers' quarrel (October 3, 1891). Yank-Hoe, whose name was reported as Ercole Castignonie, was required to return the stolen goods. A year later, in 1892, the New York Times noted that Nadine Osborne, better known as Omene, was jailed at New York's Jefferson Market Police Court for stealing valuable jewelry from her lover Edmundo de Olivieri (May 24, 1892).

With these police reports, we learn that Omene was an entirely constructed identity, a performer who understood self-promotion on the Victorian stage. Omene/Madge/Nadine's true identity, however, still remains a mystery—exactly as Omene would hope. She died of cancer in Montreal in 1899. Although reported as less than 30 years old at the time, this most likely constitutes another of Omene's biographical fabrications. Completely lost to history one century later, Omene is the ideal example of a performer who truly understood the power of the media to create a brandable identity that was profitable, far-reaching, and greater than the sum of its parts.

Related Link

The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection of Printed Ephemera

Rebekah Abramovich

Rebekah Burgess Abramovich is the collections management assistant in the Department of Drawings and Prints.