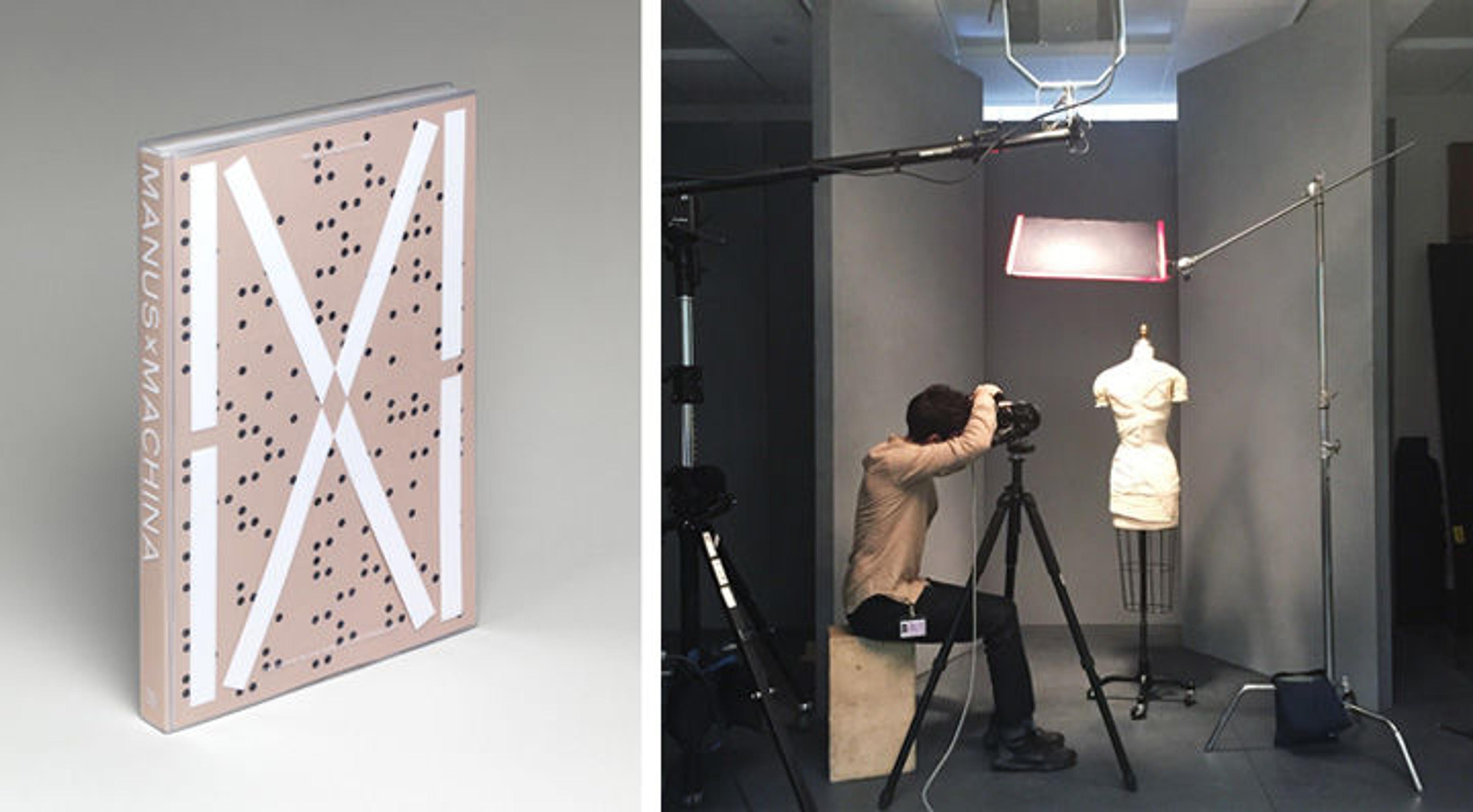

Left: Manus × Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology, by Andrew Bolton with photographs by Nicholas Alan Cope, features 178 images and accompanies the exhibition of the same name. A limited edition of 600 books comes in a hand-numbered, laser-cut box. Both are available at The Met Store. Photo by Peter Zeray. Right: Cope at work in The Met's Anna Wintour Costume Center. Photo by Francis Catania

«The catalogue for The Costume Institute's spring 2016 exhibition, Manus × Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology (open today through August 14, 2016), traces the evolution of fashion from the founding of the haute couture and the onset of mass production to the high-tech experimentation of the present day. In many ways, the process of putting together an exhibition catalogue is also a creative interaction between hand and machine.»

A critical part of this process is the photography campaign. I recently had the opportunity to speak with photographer Nicholas Alan Cope about his work and the parallels between photography and the subject of the catalogue.

Rachel High: Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology explores the evolving relationship between hand and machine in fashion. How did you emphasize these two forces in the objects you photographed?

Nicholas Alan Cope: Andrew [Bolton, curator in charge of The Costume Institute] and I discussed creating pairings and showing echoes between hand and machine in fashion. A lot of it was achieved by doing the same thing twice, almost exactly. For example, I would shoot a handmade dress that was similar in design to a machine-made dress in the same setting, in the same lighting, and with detail work that compositionally mirrored the other. The shoot focused on creating the same environment so you can see the differences.

A spread from the publication showing Cope's strategy of photographing objects in similar ways to make a direct comparison between hand and machine. The garment on the left is made entirely by machine, whereas the ensemble on the right is pleated by hand. Left: Issey Miyake (Japanese, born 1938) for Miyake Design Studio (Japanese, founded 1970). "Flying Saucer" Dress, spring/summer 1994. Courtesy of The Miyake Issey Foundation. Right: Raf Simons (Belgian, born 1968) for House of Dior (French, founded 1947). Ensemble, spring/summer 2015 haute couture. Courtesy of Christian Dior Haute Couture. Photos © Nicholas Alan Cope

The main focus was exploring details from the same direction and in the same way to reveal the difference between the handmade and the machine-made. Some differences were more obvious than others—Hussein Chalayan's garments are so heavily involved in technology that it is apparent right away that a dress is made out of fiberglass, has actuators in it, and is a mechanical piece.

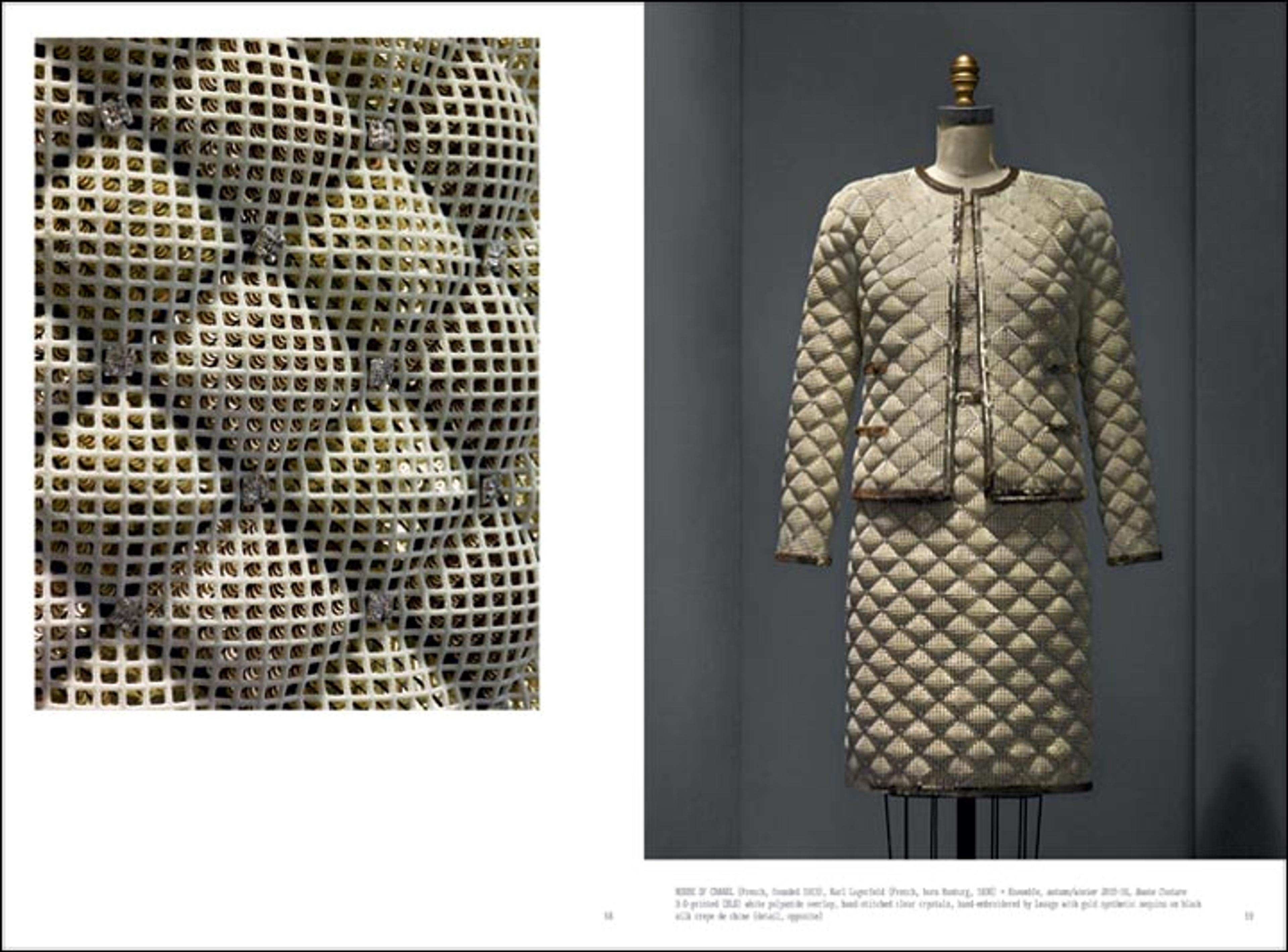

Sometimes the differences were subtle—some of the pleating work was very similar, and in the machine-made the only differences would be color or texture. Lagerfeld's designs for Chanel presented the most complex look at the difference. The 3D-printed Chanel suit takes the most time to understand because of the complexity of the piece—you really have to look at it. At first it looks like a typical quilted Chanel suit, but then you see the detail and there are sequins layered underneath it in opposing patterns. It is really intricate.

A spread from the publication with Lagerfeld's 3D-printed Chanel suit includes a detail showing the sequin pattern underneath. Karl Lagerfeld (French, born Hamburg, 1938) for House of Chanel (French, founded 1913). Ensemble, autumn/winter 2015–2016 haute couture. Courtesy of CHANEL Patrimoine Collection. Photo © Nicholas Alan Cope

Rachel High: Photography as a medium is literally the interaction of hand and the machine. The book contains "DNA" captions that show the reader what aspects of a garment are machine-made and which are handmade. Could you talk about the DNA of the photo shoot? What hand and machine elements went into producing the photographs?

Nicholas Alan Cope: The interesting thing about photography is the detail that goes into it. What separates photographers from each other is the subtlety of their approach. Lighting something at a slightly different angle or using different materials to create your set makes all the difference in the world. The approach is organic and you have to come up with a different way of doing something each time that treats the object properly, but on the other hand you have technology which has totally taken over photography—shooting digitally and capturing straight to a computer—and now there's cleanup work that happens in Photoshop to fix imperfections, dirt, and dust.

This project was all about creating a setting that would fit the subject and could be manipulated without changing the feel. Andrew and I designed a set together that we could change up so you could feel like you were in the same space but the structure would be slightly different every time. After that it is about decisions in lighting and composition of details. We picked a dramatic overhead lighting that felt appropriate for the dresses overall. The detail work was the real creative challenge. Each dress is so unique and so complex; it's a new puzzle for each dress.

This time-lapse video shows the process of photographing one of the garments. Video by Thomas Ling

Cope at work in The Met's Anna Wintour Costume Center. Photo by Francis Catania

Rachel High: In the past, you've specialized in architectural photography. Can you speak to how your background influenced your approach to photographing the garments in the book?

Nicholas Alan Cope: I started in architectural photography on my own and created a series on Los Angeles architecture which spread out into the rest of my work. Architecture has been the common thread throughout my short career. It is kind of my default; if I have some spare time and a camera, I will go walk around any city and take pictures of the architecture. I think that came into this project in the setting. Andrew wanted to integrate some of my experience with architecture into the project; it was a bit of a challenge to find a nice balance that was interesting but not distracting.

Cope with a behind-the-scenes view of the set created for the photo shoot. Photo by Francis Catania

Rachel High: Was there a specific piece featured in the catalogue that captivated you? If so, what hallmarks of the hand or machine made it engaging to you?

Nicholas Alan Cope: Iris van Herpen's ensembles are some of my favorites. I think of her more as a sculptor rather than specifically a fashion designer. I think she exemplifies fashion in new media by doing 3D printing and laser cutting and all of the other processes she's brought to fashion.

Two ensembles by Iris van Herpen that epitomize her sculptural approach to fashion. While the ensembles appear to be entirely machine made, several aspects are done by hand. On the left, the individual laser-cut feathers were sewn and placed by hand. On the right, the fringe surrounding the skirt was cut by hand. Left: Iris van Herpen (Dutch, born 1984). Dress, autumn/winter 2013–14 haute couture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2015 (2016.14). Right: Iris van Herpen (Dutch, born 1984). Ensemble, spring/summer 2010 haute couture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2015 (2016.16a, b). Photos © Nicholas Alan Cope