Left: Faience sistrum inscribed with the name of Ptolemy I (305–282 B.C.) . Ptolemaic Period. From Egypt. Faience; H. 26.7 cm (10 1/2 in.); W. 7.5 cm (2 15/16 in.); D. 3.7 cm (1 7/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1950 (50.99). Right: Sistrum column in the pronaos of the Hathor temple of Dendera (Description de l'Egypte, vol. 4, pl. 12)

«On view in the newly renovated Ptolemaic galleries is a graceful, broken-off upper part of what is known as a Hathor column, inscribed with the names of Nectanebo I, who reigned from 380 to 362 B.C., that is, 30 years before the beginning of the Ptolemaic Period. According to the information passed on about its findspot at the time of its purchase in 1928, the column originates in the Delta in Egypt, although no specific location was given.»

The History of Hathor Columns

The multifaceted goddess Hathor, mother of the Horus king and mistress of dance and jubilation, was represented by a fetish-like emblem in the shape of a pole, featuring her head or face on the top. This Hathor head on a handle became the basic form of sistra played in Hathor rituals. As a musical instrument, the head carried a sound box holding crossbars with sounding plates, which created a rustling sound. The musical instrument so characteristically represented the goddess that it inspired temple builders of the 18th dynasty to use emblem-like columns in the temples of female deities.

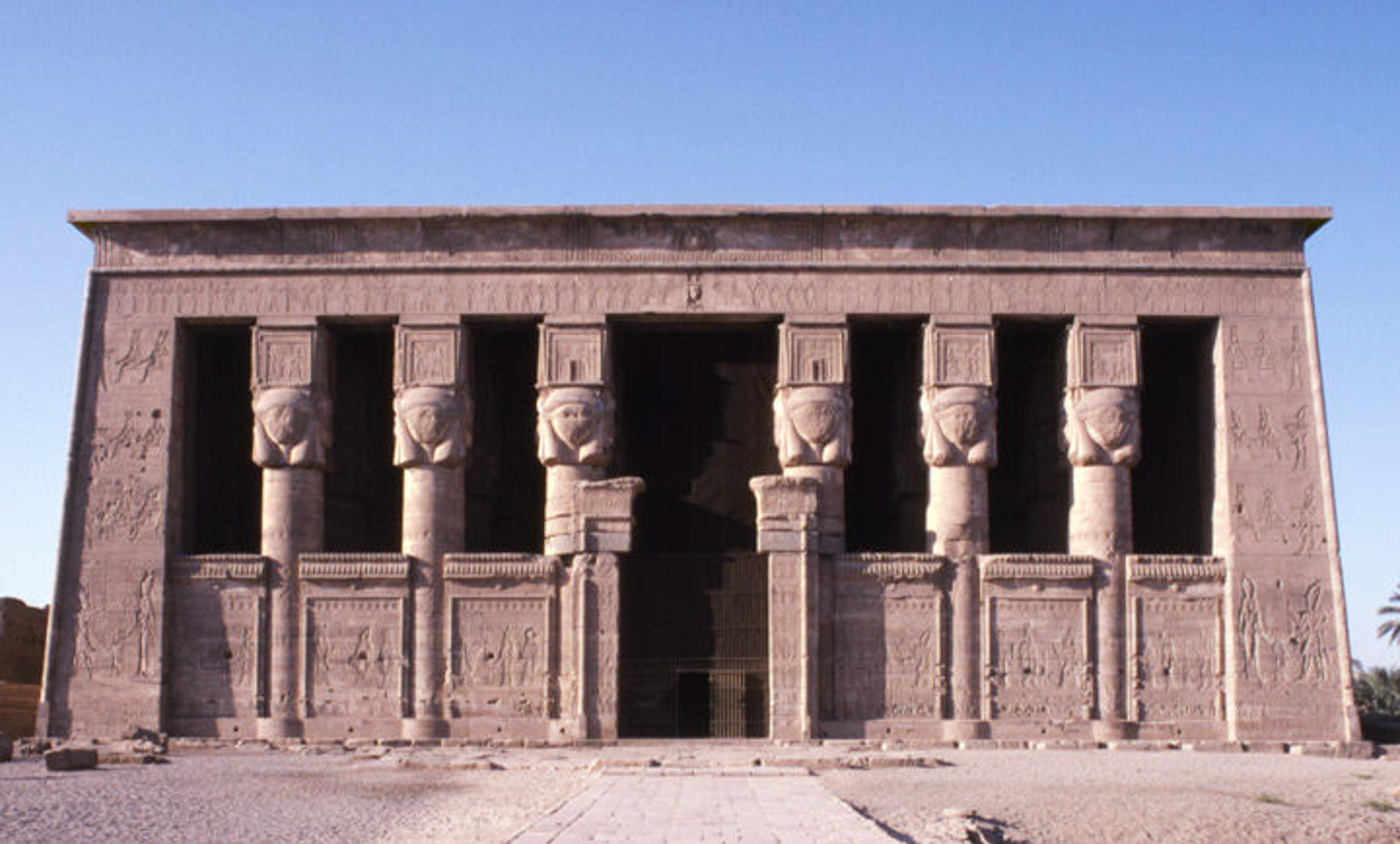

The most dramatic still-standing building with Hathor columns is the pronaos of the Dendera temple, with its 17-meter-high sistrum columns. Photo by Adela Oppenheim

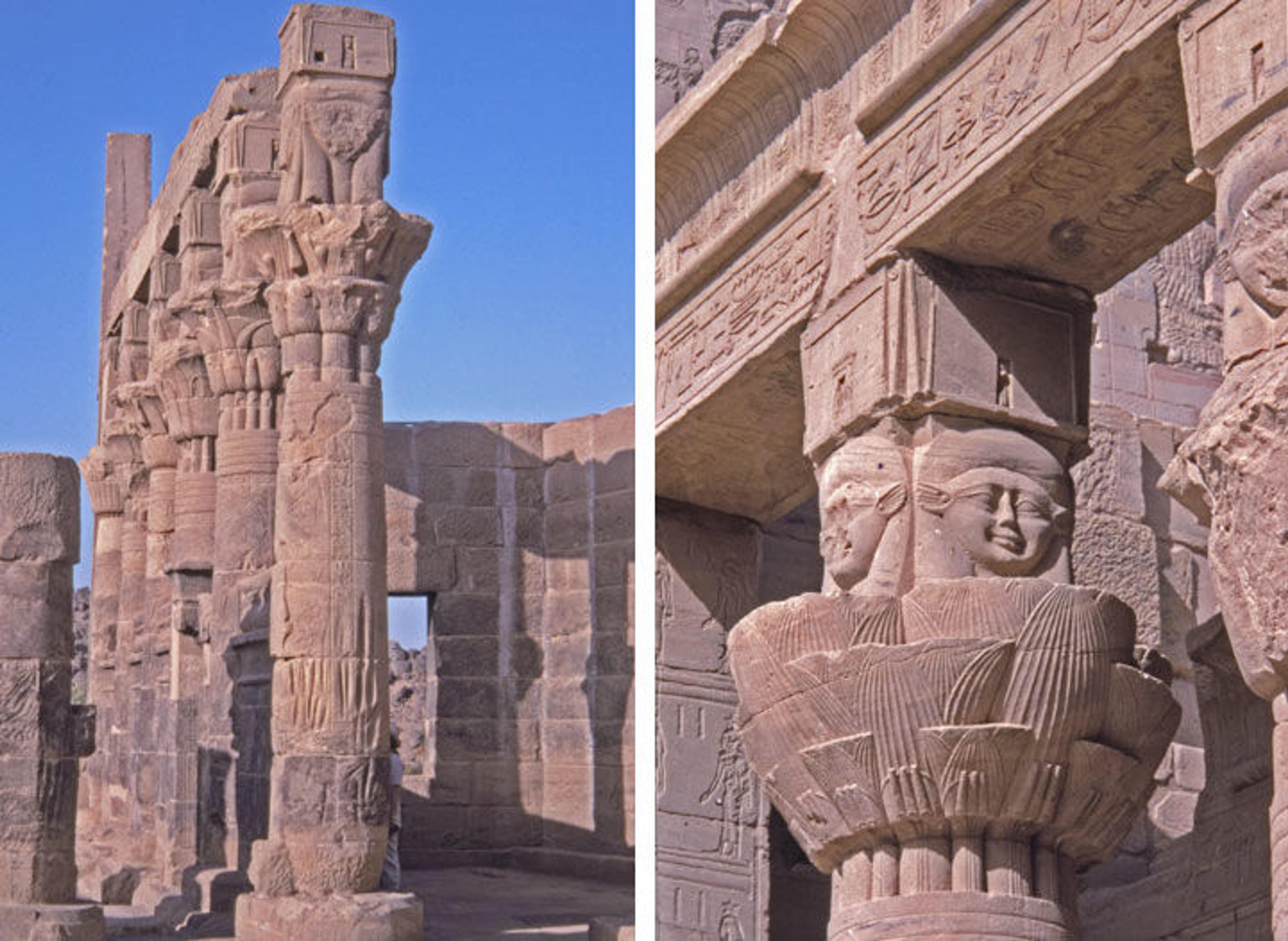

The basic form of the sistrum capital also appears in numerous variations and combinations with other capital shapes on columns and square pillars. Rows of such sistrum columns could also be understood as a kind of "petrified sound barrier," gently playing music around the sanctuary of Hathor and magically conjuring the goddess's appearance.

The kiosk of Nectanebo I (380–62 B.C.) and the birth house of Ptolemy III (246–21 B.C.) on Philae. Photos by Adela Oppenheim

Within the temples of female deities, sistrum columns appear mainly in two building types. Most examples are found in the mammisi temples (birth houses), where the birth of a young king was celebrated. These sanctuaries are surrounded by ambulatories lined with sistrum columns. The columns also appear in elegant chapels that stand on temple rooftops, with the purpose of exposing the cult images to sunlight for regeneration.

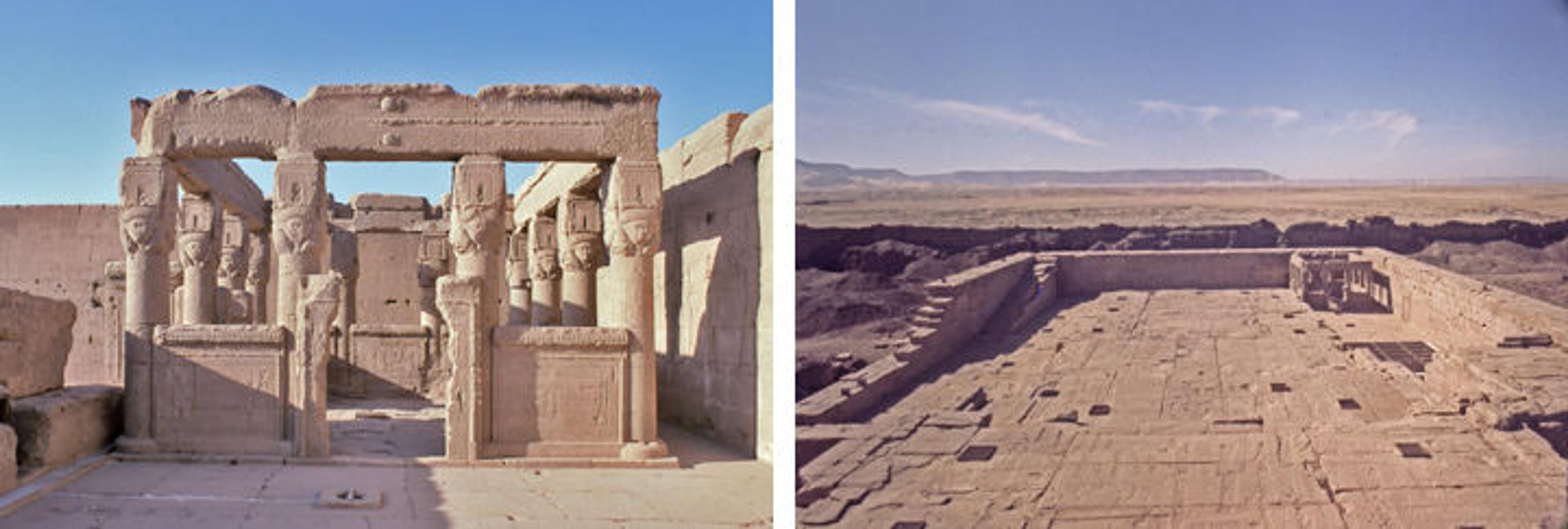

Left: The chapel on the roof of the Hathor temple of Ptolemy XII (80–51 B.C.) at Dendera. Photo by Adela Oppenheim. Right: Another view of the chapel on the roof of the Hathor temple. (Archival photo, Egyptian Department)

The Column on View

Column with Hathor-emblem capital and names of Nectanebo I on the shaft. Late Period, Dynasty 30, reign of Nectanebo I (380–362 B.C.). Possibly from Delta; From Egypt. Limestone; H. 102 cm (40 3/16 in.); W. 34.3 cm (13 1/2 in.); D. 34.3 cm (13 1/2 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1928 (28.9.7)

The Hathor face and the sistrum sound box of the column on view in the Ptolemaic art galleries are four-sided, and the sistrum is topped by a plain square slab, the so-called abacus, which would have carried the architrave. Judging from the proportions of similar examples, the column would have been around 73 inches high, just enough to let a person pass under the architrave. The shaft is inscribed on all sides with the names of Nectanebo I, alternating between "Son of Re, Lord of Appearances Nectanebo"; "Lord of the Two Lands, Lord of Rituals, Nectanebo"; "The good god Kheperkare"; and "The King, Lord of the Two Lands Kheperkare."

The column is said to originate from the Delta. Temple buildings of Nectanebo I have been found in at least 10 Delta sites but were all destroyed, making it is impossible to connect this column to a specific one. Its small size implies that it did not belong to the principal part of temple architecture and must have been part of a tiny columned kiosk, perhaps sheltered inside a temple house or to the side of the main sanctuary.

Analyzing Pigment and Reconstructing Color

The visible remains of polychromy on the column piqued our interest. To the naked eye, especially on one side of the column, there are visible traces of blue and red in the headdress and some detail in the broad collar. We suspected the blue traces were made up of Egyptian blue, which is considered to be the oldest synthetically produced pigment in the world and also the most commonly used blue pigment in ancient Egypt.

We began analyzing the color by producing an image of the column with visible-induced infrared luminescence (VIL). This technique, which we have used with startling results in the past, takes advantage of the fact that even trace amounts of Egyptian blue, a calcium copper silicate (analogous to the mineral cuprorivaite), show a strong infrared emission when illuminated with visible light. Our VIL image revealed that Egyptian blue was indeed used to create the light blue, and that it was also used in the green paint and another paint that now appears almost black to the naked eye.

Left: Some of the visible polychromy on the Hathor head. Right: An image of the column using visible-induced infrared luminescence (VIL). Image courtesy of the author

We then took minute samples of the pigments and analyzed them using polarizing light microscopy (PLM), which harnesses visible and polarizing light to assess physical and optical properties of materials. The analysis confirmed that the green color is a mix of Egyptian blue and Egyptian green (a synthetic pigment similar to Egyptian blue), and that the other color, which probably originally was a dark blue, is a mixture of Egyptian blue and charcoal black. We also used PLM to identify the yellow ochre used for the skin and background, the red ochre in the decorative elements, and the white gypsum ground. The results helped us understand the palette used by ancient craftsmen and allowed us to reconstruct what the surface would have looked like in antiquity before the loss of paint.

Finally, based on close observation of the traces still visible to the naked eye and results from the technical analyses, we created digital reconstructions of the painted surface by overlaying colors onto photographs of the column, using the side with the best paint preservation. Due to the fragmentary state of the color remains and how they altered over time, some questions inevitably arose during the digital reconstruction: How do we adequately represent the results of the analysis digitally? How should we convey texture, saturation, and thickness of paint layers? We arrived at a number of possible representations by playing with different parameters.

The column with varying degrees of saturation. The digital reconstruction in the center is the best representation of what the column might have looked like. Images courtesy of the author

The column with varying amounts of visible texture. Again, the digital reconstruction in the center is the best representation of what the column might have looked like. Images courtesy of the author

We settled on one that best satisfied our sense of what an ancient painted stone surface might have looked like and allowed us to visualize how the column might have looked in antiquity with its original polychrome. In the new galleries, the color reconstruction is shown alongside the column, one of a number of instances in which the viewer is offered an understanding of ancient uses and appearances of the artworks.

Related Link

See all posts related to the new installation of the galleries for Egyptian Ptolemaic art.