Exploring Art Deco Textile and Fashion Designs

«Pochoir, a stencil-based printing technique used to create multicolored prints, was particularly popular in the production of French illustrated pattern books from the late 19th century until the 1930s. The technique created lively images with crisp lines and vibrant colors, as seen in the design by Eugène Séguy at left (fig. 1), and was widely used in fashion journals and illustrated portfolios with designs for architecture, interiors, and textiles, many of which can be found in the collection of the Department of Drawings and Prints. A group of these publications devoted to textile and fashion designs from the Art Deco is in the process of being cataloged and digitized, giving us the opportunity to take a closer look at the idiosyncratic eclecticism of the textile designs in this period.»

Fig. 1. Eugène Alain Séguy (French, 1877–1951). PRISMES: 40 planches de dessins et coloris nouveaux, plate 20, [ca. 1930]. Pochoir, Sheet: 12 9/16 x 8 7/8 in. (31.9 x 22.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jane E. Andrews Fund, in memory of William Loring Andrews, 1933, transferred from the Library (1991.1073.196[20])

While the Art Deco was a decidedly a new style, it also maintained a strong dialogue with other artistic styles and periods, nurturing certain elements while turning away from or reacting to others. The Art Deco inherited various aspects from its direct predecessor, Art Nouveau, such as the use of geometric forms; the often flat and sometimes stylized naturalistic decorations; an predilection for exotic elements, often combined with the local; and a general interest in compositions consisting of multiple dimensions and perspectives. In line with the spirit of the times, the Art Deco also shared or adopted elements from other contemporary artistic movements. With Futurism it shared a fascination for technological advancements and the machine; with Cubism a predilection for repetition and geometric forms. A tendency towards distortion is often linked to German Expressionism, while the theatricality of the style finds a parallel in the costume and set designs for the Ballets Russes.

Textile design received much attention during this period, as fashion represented the second-largest export industry and was of great importance to the recovery of a devastated economy after World War I. This aspect is clearly reflected in the quantity of publications devoted to textile design issued in this period. The vibrancy of many of these designs can also be understood to reflect a spirit of revival and recuperation.

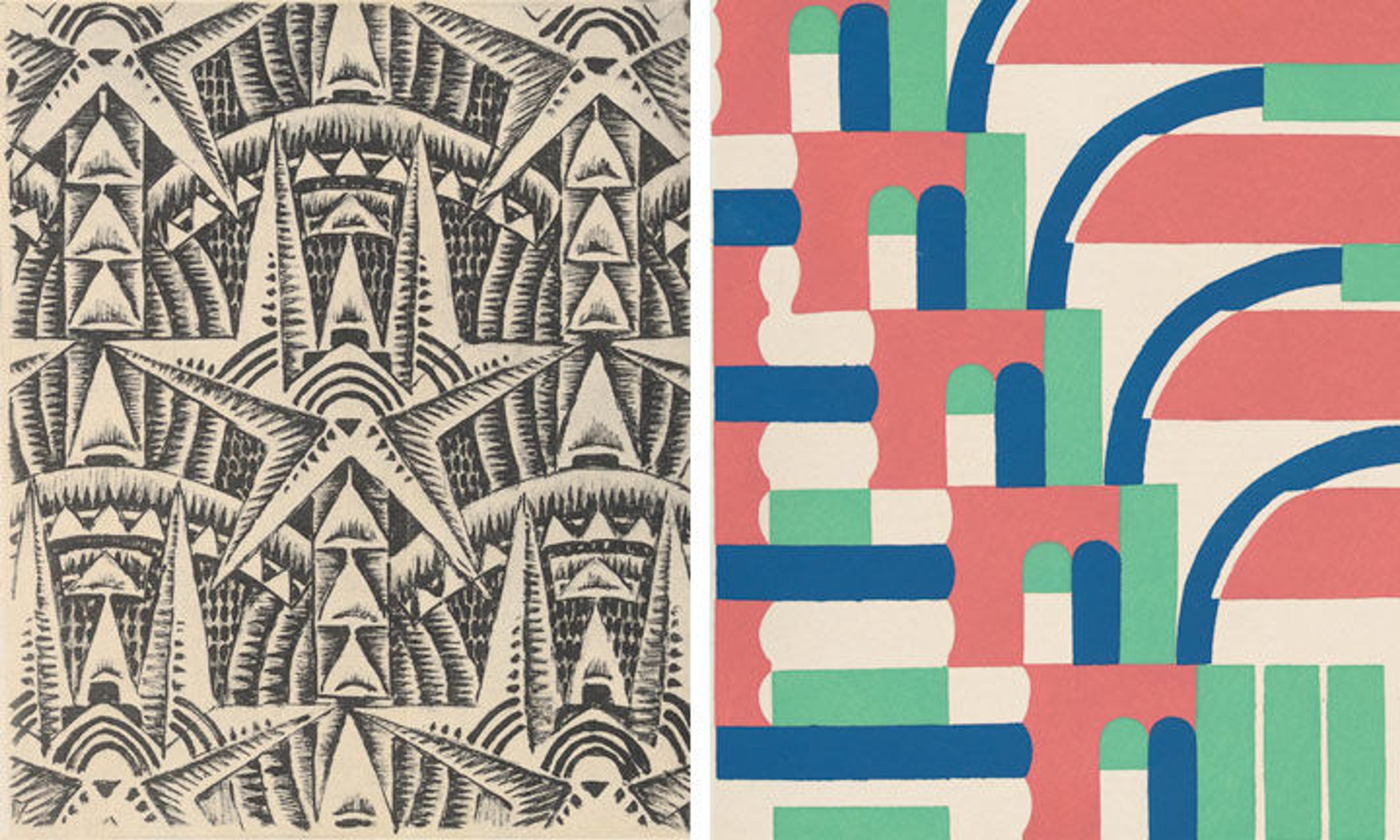

Left: Fig. 2. Jean-Émile Laboureur (French, 1877–1943). Papiers Peints et Tentures Modernes, plate 12, "Papier peint 'Le Marin,' composition de Laboureur," [1929]. Photo reproduction of a pochoir print, Sheet: 12 11/16 x 8 1/4 in. (32.3 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1929, Transferred from the Library (1991.1073.181[12]). Right: Fig. 3. Maurice-Jacques-Yvan Camus (French, born Angers, 1893–1971). Idées 1, plate 2 (detail), ca. 1933. Pochoir, Sheet: 15 in. x 11 1/16 in. (38.1 x 28.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jane E. Andrews Fund, in memory of William Loring Andrews, 1933, transferred from the Library, (1991.1073.39[1.2])

The above pattern designed by Jean-Émile Laboureur for the book Papiers Peints et Tentures (fig. 2) demonstrates the eclectic effect of the combination of elements of the various styles from which Art Deco artists took inspiration. In the repeat pattern, a French marine arrives with his sailing ship at unknown shores characterized by exotic plants, palm trees rich with fruits, and semi-savage, half-naked women who bring life to the jungle.

While a fascination with the female figure is common in both the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles, many art historians observe a transition from a rather overt sexuality in the former to the more subdued sensuous and playful semi-abstract forms of the female body, as represented in the design by Camus shown above (fig. 3).

Even more prevalent in the Art Deco designs is the association with the advancements of modern times and the machine age. An orientation toward the industrial and urban landscape—which translated into metallic color schemes and the clean ergonomic lines of industrially manufactured objects and vehicles—also invaded the realm of textiles and fashion. Details of cityscapes, Art Deco architecture, and the New York skyline, in particular, form important design motifs in the designs presented by Nicolas Sorokine in his Studio d'Arts Décoratifs (fig. 4).

Left: Fig. 4. Nicolas Sorokine. Studio d'Arts Décoratifs: Tissus par Nicolas Sorokine, plate 11, "Dessins de différents genres, de couleur sobre" (detail), [ca. 1930]. Pochoir, Sheet: 15 5/8 x 11 5/8 in. (39.7 x 29.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1925 and 1931, transferred from the Library, (1991.1073.33[1.11]). Right: Fig. 5. Serge Gladky (French, 1880–1930). Nouvelles Compositions Décoratives, 1re Série, plate 24 (detail), [ca. 1930]. Pochoir, Sheet: 12 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (32.4 x 24.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jane E. Andrews Fund, in memory of William Loring Andrews, 1943, transferred from the Library. (1991.1073.125[24])

The locomotive, other means of transportation, and new industrialized forms of production also became ubiquitous in the designs created by Serge Gladky (fig. 5).

Technological advances not only served as a subject for Art Deco designs, but also became essential in the physical production of art during the period. As such, the extensive use of pochoir as the printing technique of choice in the production of model books is not surprising, since it allowed for the creation of color illustrations with more facility than previously employed techniques such as hand-coloring, à la poupée printing, and chromolithography.

Along with industrialization, commercialization and mass production of design became the norm and also invaded the field of fashion. Paul Poiret, in particular, understood the theatrical appeal of fashion as a selling technique as early as 1911. Poiret crafted his early designs for a feminine figure who, now liberated from the corset, began to wear harem trousers, lampshade tunics, and hobble skirts.

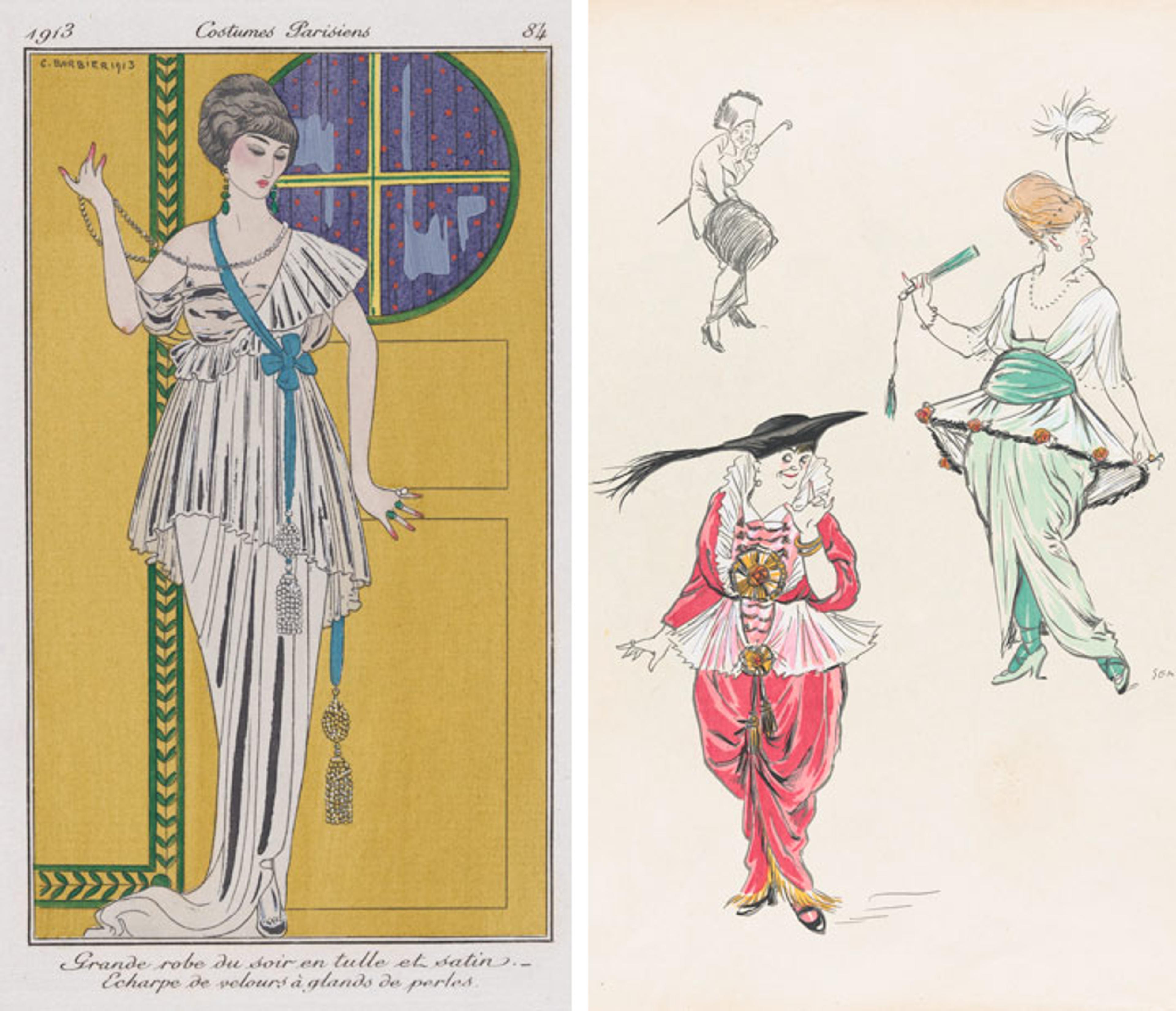

Left: Fig. 6. George Barbier (French, 1882–1932). Costumes Parisiens: "Grande robe du soir en tulle et satin; Echarpe de velours à glands de perles," 1913. Line engraving with gouache and water color, Sheet: 8 3/4 x 5 9/16 in. (22.2 x 14.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Millia Davenport, 1957 (57.546.1[2]). Right: Fig. 7. Georges Goursat [SEM] (French, 1863–1934). Le vrai et le faux chic: Musée des Erreurs, page 10, 1914. Line engraving and pochoir, Sheet: 17 7/8 x 12 13/16 in. (45.4 x 32.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1962 (62.652.7[11])

In his Le vrai et le faux chic: Musée des Erreurs (The True and False Chic: Museum of Errors) of 1914, Georges Goursat (better known as SEM) mocked the polemics of Art Deco fashion and, in particular, the style of Paul Poiret. He criticized the exotic, over-the-top fashions with their bold designs, and instead advocated for a simpler, slender form, plain fabrics, and subtle colors that would come to be known as the garçonne ("New Woman") of the Art Deco.

The development of the slender figure of the garçonne was a direct result of the changing position of women in society, especially after they were granted the right to vote by the United States in 1919. The "New Woman" had a taste for fashionable, androgynous, and more form-revealing clothing, which contemporaries simultaneously loved and criticized. The characteristic silhouette consisted of an elongated, boyish figure; tubular garments that revealed legs; imaginative, streamlined shoe designs created by the likes of Salvatore Ferragamo and Roger Vivier; a short haircut, covered by a cloche hat; and a long, dangling pearl necklace around the neck.

For Poiret, the garçonne was a symbol of the decay of French fashion, and he predicted it would severely damage its stature. Nevertheless, at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, the garçonne was chosen to symbolize the epitome of Parisian fashion.

Fig. 8. Sonia Delaunay, née Terk (French [born Russia], 1885–1979). Plate 2 from Sonia Delaunay: ses peintures, ses objets, ses tissus simultanés, ses modes, [1925]. Pochoir and relief process, Sheet: 14 15/16 x 21 15/16 in. (38 x 55.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1968 (68.580.1[2])

The designs of Sonia Delaunay (figs. 8, 9) seem to form a middle ground between the two opposites: promoting striking colorful, geometric patterns to create short dresses for a modern, active woman. Applying a painter's approach to textiles, the fashions of Delaunay's "simultaneous experiments" perfectly reflect the eclectic, abstract aesthetic of the late Art Deco.

Fig. 9. Sonia Delaunay, née Terk (French [born Russia], 1885–1979). Plate 18 from Sonia Delaunay: ses peintures, ses objets, ses tissus simultanés, ses modes, [1925]. Pochoir and relief process, Sheet: 14 15/16 x 21 15/16 in. (38 x 55.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1968 (68.580.1[18])

Both a reaction to and an escape from the perplexing contrasts of modern times as well as the monumental changes and apocalyptic events of the early 20th century, textile design maintained a sense of positivity and fantasy in the Art Deco period. This optimism—like the liberated, dancing figure of the garçonne—would disappear at the end of the 1930s when a second, even more devastating war shook the foundation of modern society.

Left: Fig. 10. G. Barbier (French, 1882–1932). Costumes Parisiens 112: Manteau de velours blanc brodé de perles; Robe de damas blanc; Souliers roses, 1913. Line engraving with gouache and water color, Sheet: 8 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (22.6 x 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Millia Davenport, 1957 (57.546.14[1]). Right: Fig. 11. André Stéfan (French, active early 20th century). Costumes Parisiens 138: Robe de satin pékiné à volants de nansouk, 1914. Line engraving with gouache and water color, Sheet: 8 7/8 x 5 9/16 in. (22.5 x 14.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Millia Davenport, 1957 (57.546.25[2])

The spirit of the times has been preserved, however, in the many artworks and design objects made in this period. The textile and fashion design publications, in which not only the designs but also their vibrant colors have been so beautifully preserved, form a kind of time capsule, giving us a glimpse of the Parisian lifestyle and the elegant eclecticism of the fashions during the heydays of the Art Deco period (figs. 10, 11).

Related Links

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "French Art Deco"

Now at The Met: "Discussing the Rise of French Art Deco with Author Jared Goss" (April 29, 2015)

Laura Beltran-Rubio

Laura Beltran-Rubio is a research volunteer in the Department of Drawings and Prints.