Modeling the World: Ancient Architectural Models Now on View

This small platform surmounted by a temple with a peaked roof may have once served as the lid for an incense burner. Temple model, 200 B.C.–A.D. 300. Colima, Mexico. Ceramic; H. 7 1/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, From the Collection of Nina and Gordon Bunshaft, Bequest of Nina Bunshaft, 1994 (1995.63.5)

«The Metropolitan Museum's permanent collection is unusually rich in archaeological architectural effigies—often called models—from around the globe, including works from Middle Bronze Age Syria, Ancient Egypt, and Han Dynasty China. Now, joining these remarkable works under the Met's roof are the fifty Precolumbian models featured in the exhibition Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view through September 18, 2016.»

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods in Europe, architectural models were, as they still are now, an important tool in the collaboration between architects and patrons. An architect's scale representation of a structure was a means to work out ideas, show patrons design possibilities, provide a platform for negotiations, or sometimes even to function as guides for builders. Most archaeological models, in contrast, do not seem to have served such purposes, or if they did so, then only rarely. Some Ancient Near Eastern and Precolumbian models served primarily as ritual vessels, essential features of funerary practice. Other ancient architectural effigies, such as those of the Eastern Han dynasty, were about ensuring favorable conditions in an afterlife—prototypes only in the sense that they were intended to provide comfortable accommodations for the deceased in the great beyond.

One of the oldest examples in the Museum is a striking Middle Bronze Age vessel from Syria that depicts a figure grasping the hindquarters of two lions at the top of a two-story building. Pierced from top to bottom, the model allowed for the flow of liquid libations during religious rites held in a temple or sanctuary.

Left: Cult vessel in the form of a tower with cylinder seal impressions near the top, ca. 19th century B.C. Middle Bronze Age. Syria. Ceramic; H. 31.4 cm, W. 8.3 cm, D. 11.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1968 (68.155)

Clay models from ancient Egypt, often called "soul houses," are also thought to be a type of offering vessel designed to receive libations. Soul houses and other larger models in wood from ancient Egypt are now on view through January 24, 2016, in the exhibition Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom. Unlike the clay soul houses, which are associated with simple graves, the wood models were more commonly found inside elaborate burials and tombs.

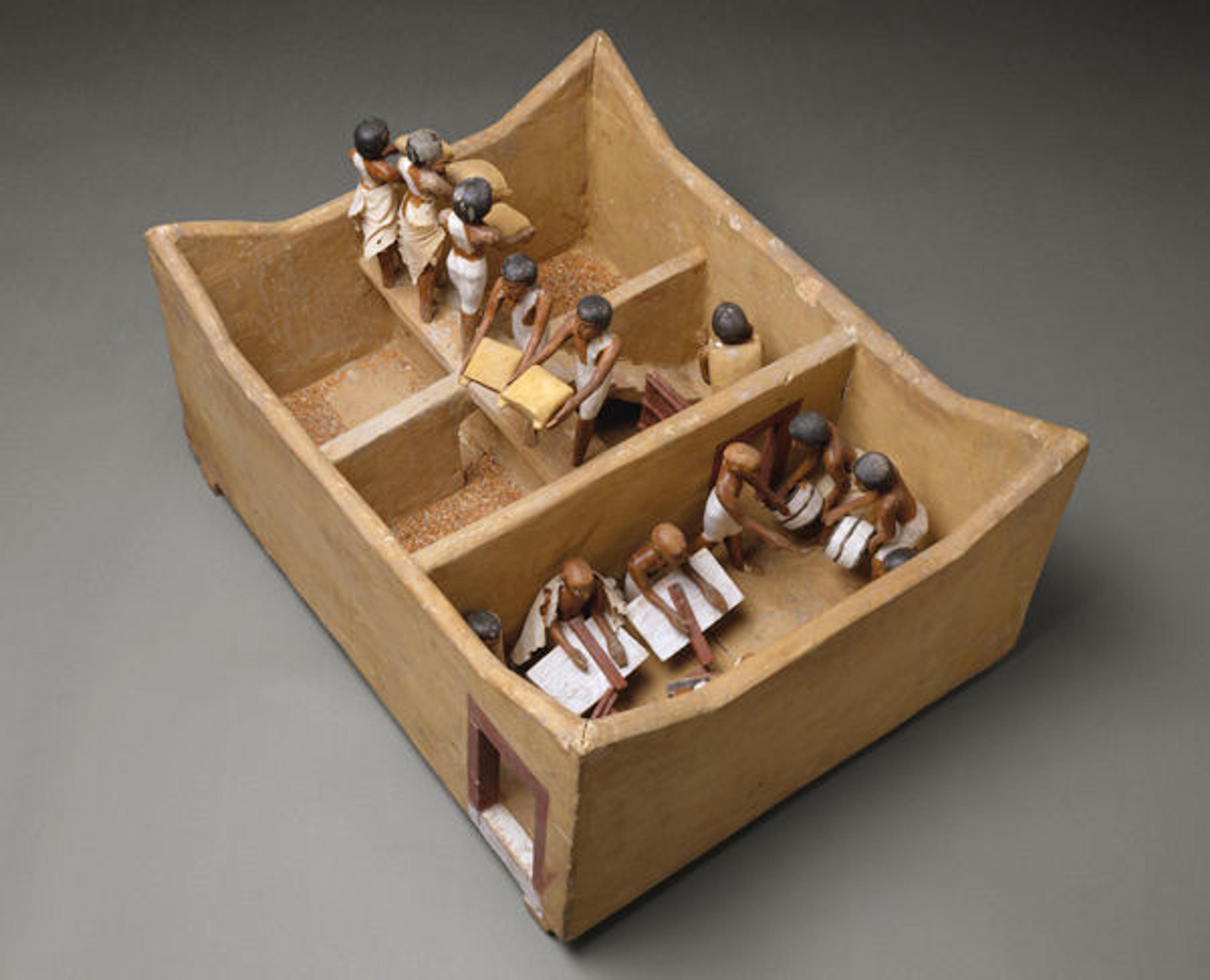

Several remarkable models from the tomb of Meketre, a royal steward who served under King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II ( ca. 2051–2000 B.C.) until the early reign of Amenemhat I (ca. 1981–1975 B.C.), depict a range of activities and spaces, including a granary, stable, and garden. These beautifully detailed models seem to have been made to provide the prosperous deceased a comfortable afterlife, and they speak to us of the standard of living of the upper echelons of Middle Kingdom society as well as to the labor necessary to maintain that lifestyle.

Model of a Granary with Scribes. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of Amenemhat I (ca. 1981–1975 B.C.). Wood, plaster, paint, linen, grain; L. 74.9 (29 1/2 in.), W. 56 cm (22 1/16 in.), H. 36.5 (14 3/8 in.), average height of figures: 20 cm (7 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920 (20.3.11)

The Met's collection also includes exquisitely detailed architectural models from Han dynasty China (206 B.C.–A.D. 220), which appear to have been placed in tombs for use in the afterlife. As with the wood examples from Egypt, Eastern Han models were designed to emulate full-scale architecture and serve as stand-ins for the real thing, ensuring the comfort of the elite deceased. As with the Egyptian models mentioned above, those from the Eastern Han likewise include such utilitarian agricultural structures such as wells, granaries, and pens for livestock, all essential elements in Han settlements. Multistoried watchtowers, a common security feature on larger estates, were also rendered as models, symbolizing the enduring power and prestige of the estate owners after death.

Right: Central watchtower, 1st–early 3rd century. China, Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 A.D.). Earthenware with green lead glaze; H. 104.1 cm (41 in.), W. 57.5 cm (22 5/8 in.), D. 29.8 cm (11 3/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Dr. and Mrs. John C. Weber Gift, 1984 (1984.397a, b)

Most Precolumbian architectural models were also presumably placed in burials, and some, such as the Nayarit models that depict feasts and ball games, were almost certainly conceived as embodiments of a desired afterlife similar to those from ancient Egypt and the Eastern Han. Others may have symbolically represented important buildings or other ritual architecture, or served as dwellings for divine beings. These models—in clay, stone, wood, and metal—were distillations of ideas about the symbolic significance of architecture: as the embodiment of political power, for example, or as the focus of ritual practice. These represent a variety of building types—from modest domestic structures to elaborate palaces, small temples to large ball courts—and range from exquisite small objects sculpted in hard stone using a minimum of detail, to larger representations in ceramic and wood "inhabited" by dozens of individuals.

Such a diverse group of objects likely served different intentions and functions, which we are only now beginning to interpret and, perhaps, understand. For example, advances in Maya epigraphy—the study of inscriptions—have made available new texts that shed light on Precolumbian models. Thanks to studies by David Stuart, Stephen Houston, and their colleagues, we now know that an inscription on a stone house form from Copan, Honduras, tells us that it is a "sleeping places for the gods" (waybil k'uh), showing explicitly that architectural models were seen as dwellings for the divine, temporary abodes for gods and goddesses while in the human world.

House form, A.D. 550–900. Honduras, Copan. Maya. Stone (Rhyolite); Height: 15 3/4 in. (40 cm), Width: 14 9/16 in. (37 cm). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge (92-49-20/C20, C21)

One of the most striking features of many architectural models from both Mesoamerica—the area spanning from central Mexico to northern Costa Rica—and the Andean region of South America is that they are also vessels. In a sense, such vessels are a play on the concept of architecture itself, which writ large is a type of "container." Yet many Precolumbian architectural models emulate the literal form of bottles, jars, and other vessels. Did they contain libations that were used in funerary ceremonies, or were they meant to contain sustenance for another life? Some of the vessel shapes, such as the stirrup-spout bottles of ancient Peru, are impractical for earthly substances—they are difficult either to fill or to empty—and it could be that at least some of these architectural vessels were meant to contain something more ethereal or evanescent, such as a divine essence, in the way that Maya gods were thought to inhabit their models.

This vessel is modeled in the shape of a spiral platform surmounted by an open-sided structure with a figure inside. Architectural vessel, A.D. 400–600. Peru. Moche. Ceramic; H. 8 7/16 x W. 5 1/2 in. (21.51 x 13.97 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Nathan Cummings, 1963 (63.226.13)

As diverse as the Metropolitan Museum's collection of ancient architectural models is, these engaging works all speak to an enduring tradition of capturing the character of key structures and their associated meanings in miniature. Intimately bound to ideas of time and place, these models leave us with indelible images of lost worlds.

Additional Reading

Aruz, Joan. "Sealing beyond the Storeroom Door in the Aegean and the Near East." In Studi in onore de Enrica Fiandra: Contributi di archaeologia ega e vicinorientale (Studi egei e vicinorientali 1), edited by Massimo Perna, 29–53. Naples: Institute for Aegean Prehistory, 2005.

Fash, Barbara W. The Copan Sculpture Museum: Ancient Maya Artistry in Stucco and Stone. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press, 2011.

Houston, Stephen, and David Stuart. "The Way Glyph: Evidence for Co-Essences among the Classic Maya." In Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 30. Washington, D.C.: Center for Maya Research, 1989.

Jones, Julie. Houses for the Hereafter: Funerary Temples from Guerrero, Mexico, from the Collection of Arthur M. Bullowa. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

Millon, Henry A., and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, eds. The Renaissance from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo: The Representation of Architecture. Milan: Bompiani, 1994.

Millon, Henry A., ed. The Triumph of the Baroque: Architecture in Europe, 1600–1750. Milan: Bompiani, 1999.

Oppenheim, Adela, Dorothea Arnold, Dieter Arnold, and Kei Yamamoto. Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Pardo, Cecilia, ed. Modelando el mundo: Imágenes de la arquitectura precolombina. Lima: Asociación Museo de Arte de Lima, 2011.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Patricia Sarro, James Doyle, and Juliet Wiersema. Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Related Links

Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view October 26, 2015–September 18, 2016

Now at the Met: "When Mummies Were the Life of the Party" (October 30, 2015)

Joanne Pillsbury

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of Ancient American Art, is a specialist in the art and archaeology of the Precolumbian Americas. Pillsbury earned her PhD from Columbia University. She was previously Associate Director of the Getty Research Institute and Director of Precolumbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks. She is the author, editor, or co-editor of numerous publications, including the three-volume Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900 (2008), the Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Award recipient Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks (2012), and Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas (2012), which was awarded the Association for Latin American Art Book Award.