How Was It Made? The Process of Creating Art

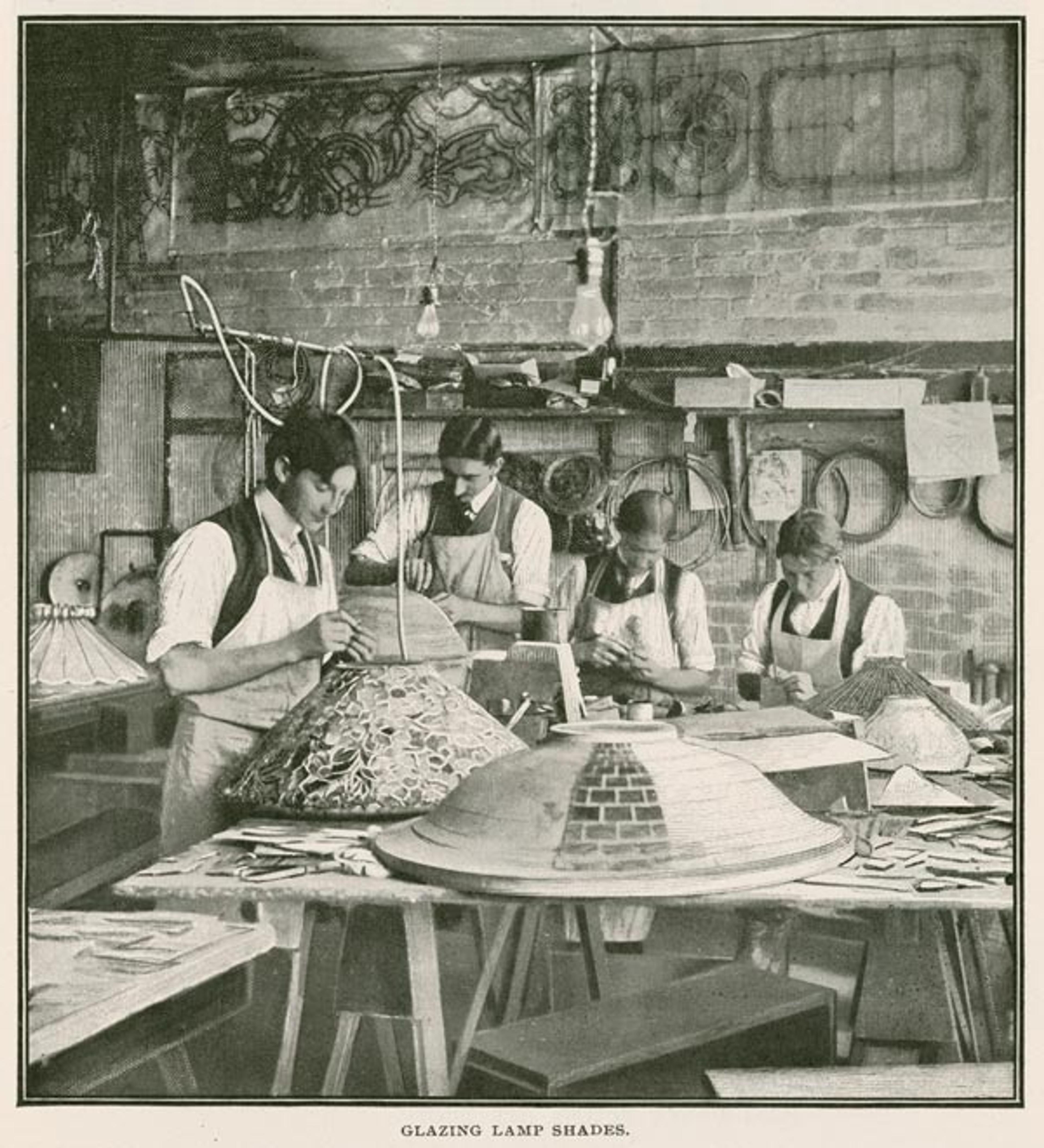

Workers in the Tiffany Studios lamp department ca. 1898, from The Cosmopolitan: A Monthly Illustrated Magazine, January 1899

«Have you ever viewed an artwork and wondered how it was made? The Met's collection is full of art that inspires us to ponder its creation, but the Museum rarely reveals the many steps that were taken to create the final work of art.»

Some of the questions that often come to mind when walking through the galleries include: Who made this? What is it made of? How was it made? How long did it take? A small installation in gallery 774 aims to highlight the processes and tools that were used either to reproduce or create two important works in our collection: Tiffany & Co.'s 1875 masterwork, The Bryant Vase, a birthday gift for the journalist and poet William Cullen Bryant; and Tiffany Studios' leaded glass lampshade for the "Tulip" lamp.

Left: The Bryant Vase, 1875–76. Manufactured by Tiffany & Co. (1837–present). American. Silver; 33 1/2 x 14 x 11 5/16 in. (85.1 x 35.6 x 28.7 cm); diam. 11 5/16 in. (28.7cm); 452 oz. 16 dwt. (14084.2 g). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Cullen Bryant, 1877. Right: "Tulip" lamp, 1907–12. Tiffany Studios (1902–32). Leaded Favrile glass and patinated bronze with a reticulated blown glass base; 23 1/8 in. (58.7 cm); body diameter: 14 in. (35.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard L. Chilton Jr., 2011 (2011.99.3)

The installation features the molds that were used to replicate The Bryant Vase through a process called electrotyping, and an accompanying video illustrates this complex and fascinating technique. Scientifically inclined visitors might find it interesting that electricity and charged ions are central to this process.

A mold used to replicate The Bryant Vase, on display in gallery 774

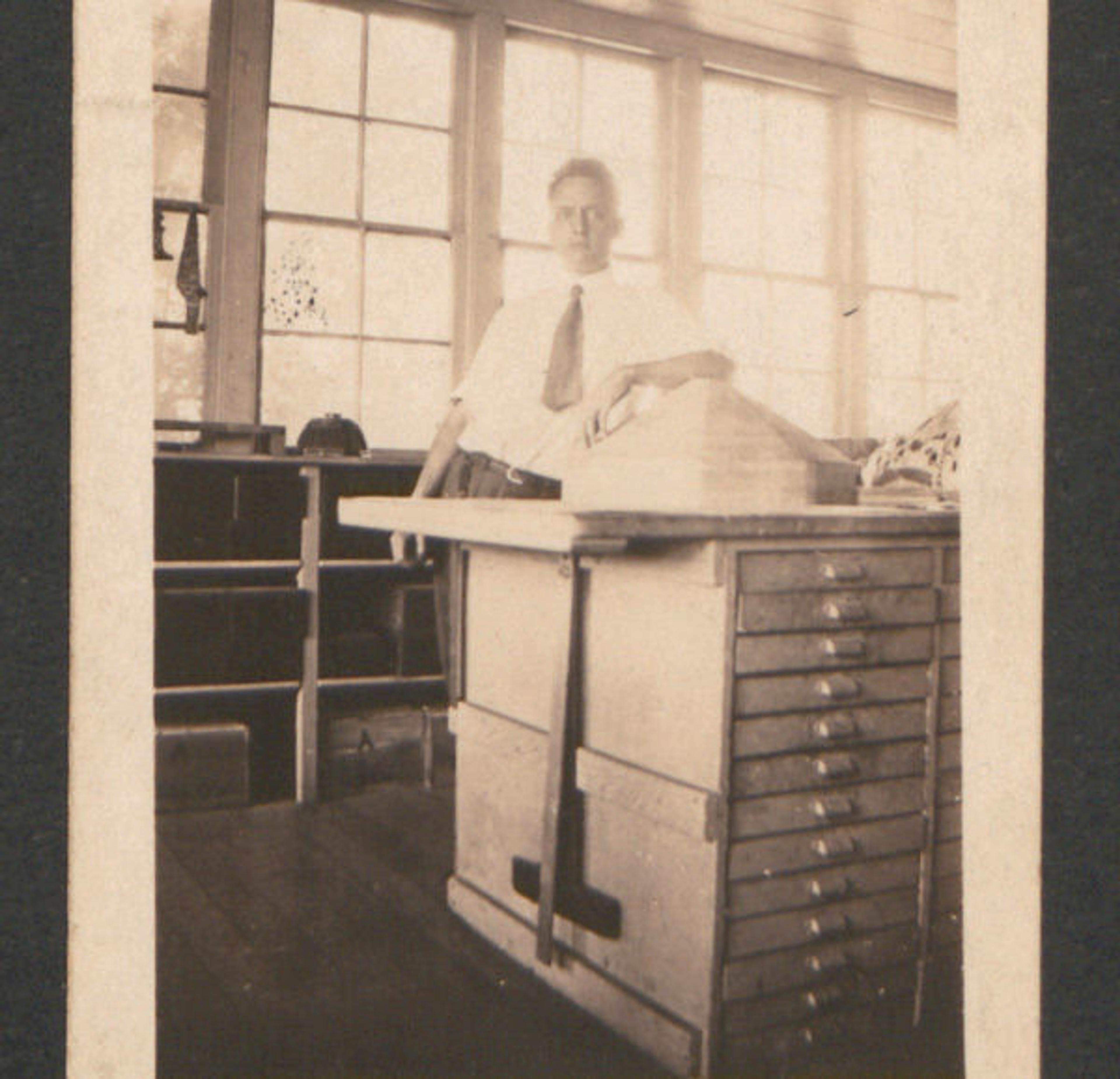

Nearby, the workbench and tools utilized by John Dikeman—the last head of the Tiffany Studios lampshade shop—help us to visualize the studio in which Tiffany lamps were produced.

John Dikeman at his work bench, Tiffany Studios, 1921. Photograph, Department of American Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

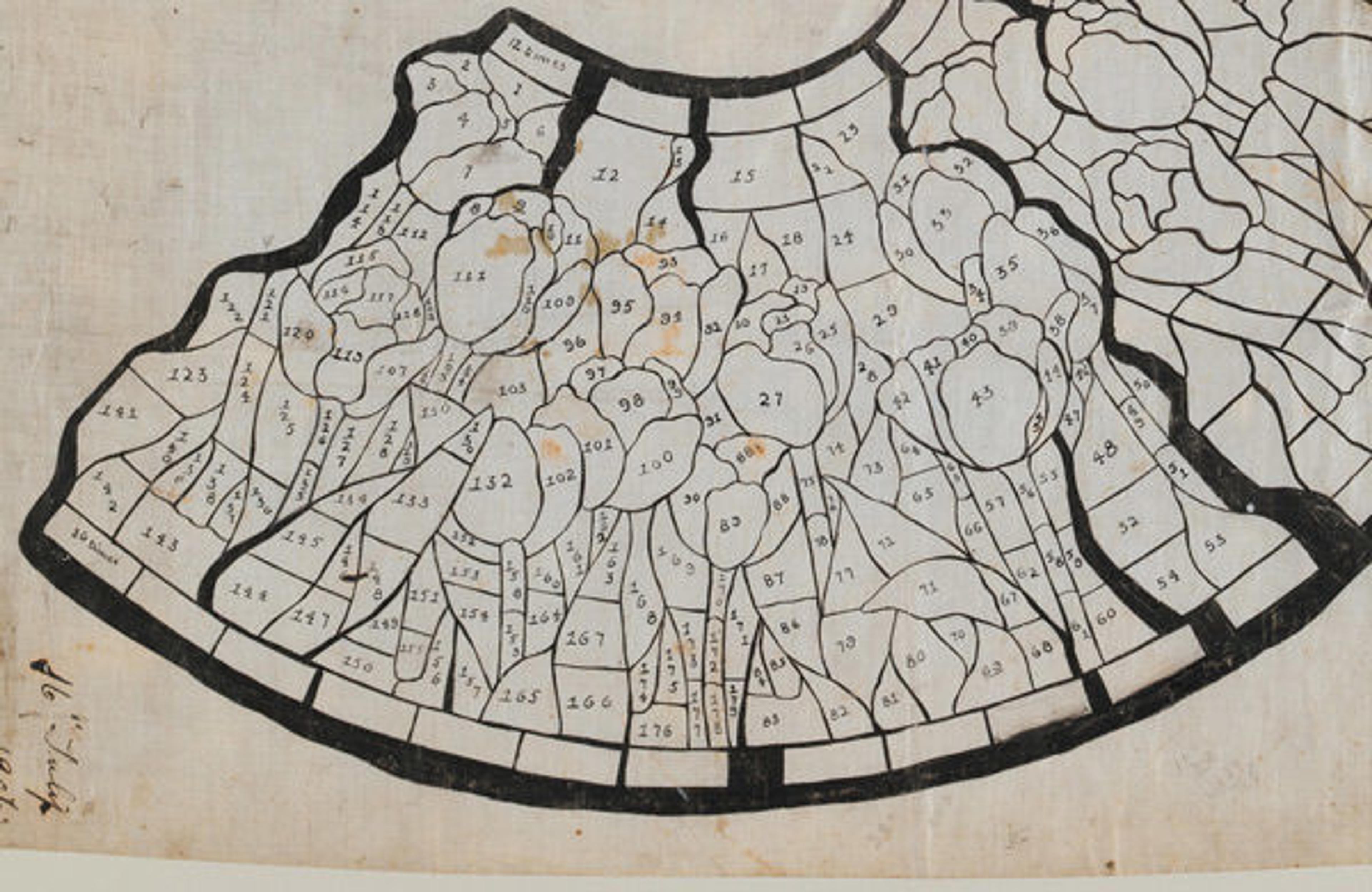

Long before any pieces of glass were cut and assembled on a wooden mold, like the one Dikeman is leaning on in the photograph above, an approved watercolor design of the shade was translated into a cartoon and sample pattern, which suggested a color for each piece of glass.

Notice how the cartoon is numbered; these numbers correspond to the individual cardboard or brass templates used to cut the glass. Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933). Cartoon for tulip shade, ca. 1906. Tiffany Studios (1902–32). Ink on glazed fabric; 25 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. (64.1 x 74.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Fred and Nancylee Dikeman, in memory of his father, John Dikeman, 1980 (1980.497.14)

An artist, usually a woman, was responsible for the selection and cutting of glass, and a craftsman, most likely a man, was in charge of soldering the pieces together.

Sample pattern for a lamp shade, 1900–1907. Tiffany Studios (1902–32). American. Metal, cloth, glass; a: 9 1/2 x 16 1/16 in. (24.1 x 40.8 cm); b: 9 9/16 x 5 1/2 in. (24.3 x 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Fred and Nancylee Dikeman, in memory of his father, John Dikeman, 1980 (1980.497.5)

We hope that shedding some light on the process of how these artworks were made will make them even more interesting. Come and see it for yourself!

Adrienne Spinozzi

Adrienne Spinozzi joined the American Wing in 2007 and oversees the museum’s American redware, stoneware, and art pottery collections. She recently curated Shapes from out of Nowhere: Ceramics from the Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection (2021), an exhibition of 20th- and 21st-century ceramics. Her current project is Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina (2022), a presentation of 19th-century stoneware with a focus on the contributions of enslaved potters. She is a graduate of Hartwick College and the Bard Graduate Center in decorative arts, design history, and material culture.

Selected publications

MetPublications: Selected Publications by Adrienne Spinozzi

Met Articles: Articles by Adrienne Spinozzi

Medill Harvey

Medill Higgins Harvey oversees the collections of American silver, jewelry, and other metalwork, as well as mid-nineteenth-century furniture. She joined the staff of the American Wing to direct research for the exhibition Art and The Empire City (2000). She is co-author of Early American Silver in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013) and contributed to the 2011 and 2009 reinstallations of the American silver and jewelry collections, as well as the exhibition, Silversmiths to the Nation (2007). Her current project is Collecting Inspiration: Edward C. Moore at Tiffany & Co. (2024). She holds a BA in art history from Dartmouth College and was awarded an MA in decorative art history by the Cooper-Hewitt Museum/Parsons.

Selected publications

MetPublications: Selected publications by Medill Higgins Harvey