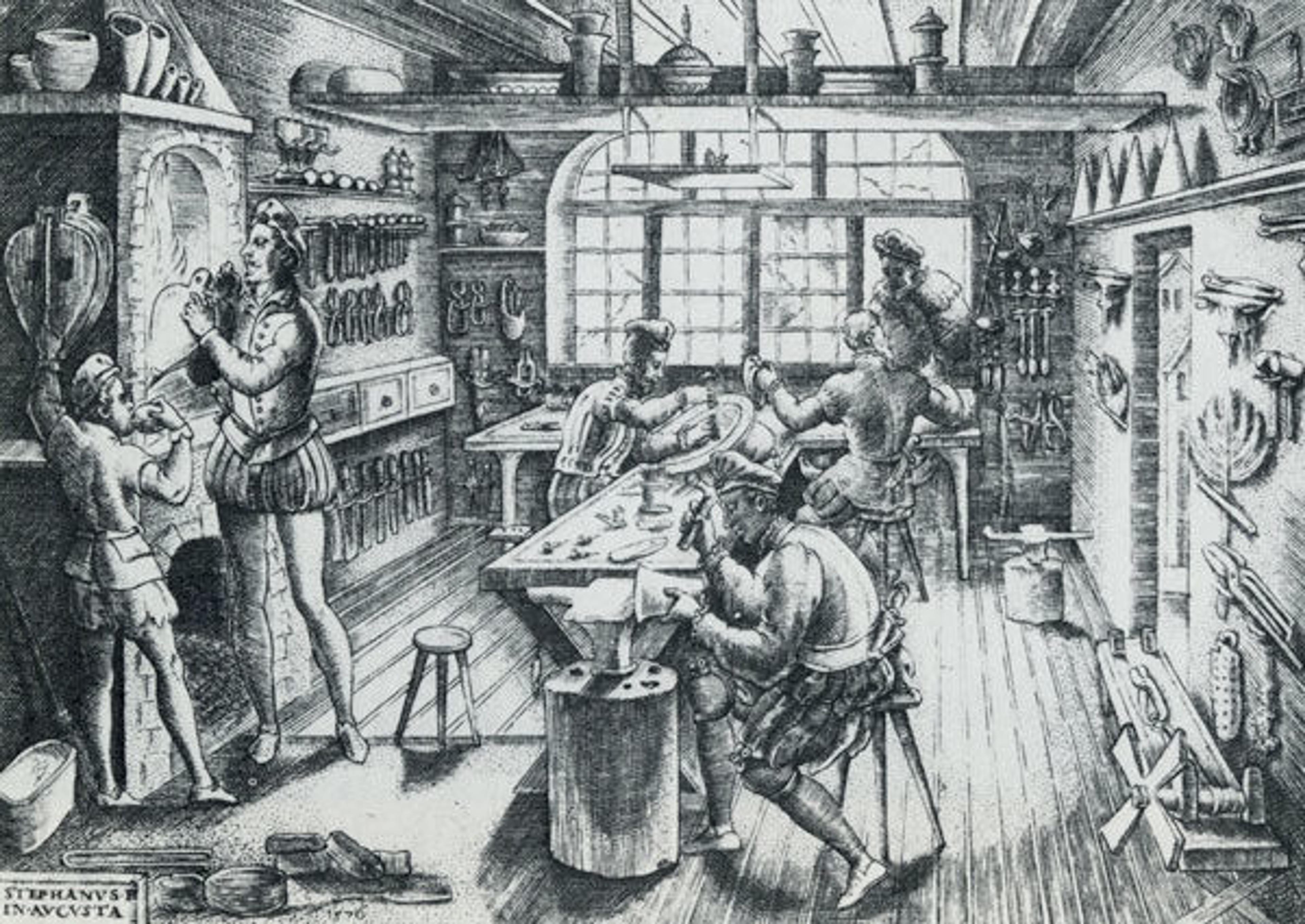

Engraving by Éttienne Delaune (1518–1583) of a goldsmith's workshop in Augsburg, Germany, 1576. From John F. Hayward, Virtuoso Goldsmiths and the Triumph of Mannerism, 1540–1620 (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications, 1976), plate 3.

«Munich, June 21, 1868: The premiere of Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg—an opera portraying the well-known and respected guild of the Meistersingers, who entertained German audiences with poetry and song from the fourteenth through the sixteenth century. While it wouldn't be a proper opera without some romance and intrigue thrown in for good measure, it was the complex Renaissance guild system that provided such rich fodder for one of Wagner's only original plotlines. The story highlights an essential tension within the guilds, between artistic spontaneity and strict regulation, and illustrates how this tension was transcended to create incredible art.»

The objects featured in Hungarian Treasure: Silver from the Nicolas M. Salgo Collection, on view through October 25, also demonstrate the fruits of this system. Goldsmiths throughout Europe worked within the rigid constraints of their guild, carrying out only approved commissions and performing the tasks which they were permitted. Despite working within a seemingly oppressive system—one in which workers were threatened with heavy fines for violations, or even expulsion from the guild altogether—there arose an output of spectacular, enduring works of art.

Medieval craftsman were the first to band together in groups called guilds, in an attempt to protect their livelihoods and maintain the integrity of their craft. Goldsmith guilds were established as early as the fourteenth century. Due in large part to the high value of their raw materials, used for coinage as well as works of art (as discussed in my previous post, "Worth Their Weight"), the goldsmith guilds were among the most highly respected throughout Europe. Although guild membership was a professional endeavor, these organizations were involved in many parts of their members' daily lives: elderly masters, the sick, and widows of deceased members were cared for by the membership, and disputes could be settled at weekly guild meetings.

Their governing bodies determined all operations of the craftsmen—including standards for the purity of their materials, the requirement of maker's marks, and even how many employees a master goldsmith could have and for how long. In Hungary, a master goldsmith (called a mester in Hungarian) could have two journeymen (legény) and two apprentices (inas) at any given time. Two masters in each guild were elected to the position of magister cehae, head of the guild, acting as wardens with great power over the organization. Among many other duties, they judged the masterpieces made by journeymen required for entrance to the guild and approved all finished objects before they left the workshop.

Silver that passed muster was stamped with a town mark, which, along with the maker's personal mark, now helps modern scholars to identify the town and workshop of origin of many objects. More importantly for the original owners of these objects, the town mark served as a guarantee of the quality of the piece, indicating that it met the town's standards for the purity of the silver. If the guild wardens found any silver to be of inferior quality, the master would be fined; a second infraction resulted in expulsion from the guild.

On the underside of this beaker, the town mark of Brassó (in present-day Romania) can be seen on the left, and the maker's mark of Michael May II on the right. Michael May II (active 1731–76). Beaker, ca. 1740. Hungarian, Brassó. Silver, partly gilded; Overall: 6 x 4 1/4 in. (15.3 x 10.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Salgo Trust for Education, New York, in memory of Nicolas M. Salgo, 2010 (2010.110.54)

The history of the goldsmith guilds, and indeed the guilds of most craftsmen, is a story of strict regulation, but it is also replete with appeals, loopholes, and rule-breakers. Powerful rulers appealed to the governing members of local guilds on behalf of their favored craftsmen, lobbying for their admission. A few craftsmen avoided the guild system entirely, choosing instead to work as "court artists" who fulfilled the whims of their particular patron. Some of the finest surviving silver objects from this period are entirely without marks to indicate by whom they were made, since these marks were not required or regulated outside of guild operations.

In the absence of royal intervention, and since anything from minor infractions to possessing inferior lineage could preclude one's admission to the guild, some rejected craftsman continued practicing in secret, persuading members who had attained master status to sell their work as the master's own. Ambitious journeymen who feared being relegated to such a fate might consider marrying the widow of a deceased master, which could greatly increase their chances of approval from the guild.

A typical apprenticeship lasted three to four years. During the next stage of their career, as journeymen, these craftsmen received hands-on work experience and, as their title suggests, were required to travel as part of their education, visiting other workshops and seeing the different styles employed by other artisans. When individual craftsmen acquired new patterns or engravings on these journeys, they became the property of his entire guild. It is surprising that despite the many restrictions on a goldsmith's professional activities, he was indeed allowed to publish his designs. It was this particular freedom, however, that allowed all of the guilds to mutually benefit from the innovations of their fellow craftsmen, thus enriching the entire European artistic community. Many such drawings survive, including an example by the Hungarian Andreas Tar of Kolozsvár (present day Cluj, in Romania), made around 1680 (below).

Andreas Tar (Hungarian, active 1677–1683). Floral Arrangement with Birds, ca. 1680. Museum of the City, Kolozsvár

A number of the objects included in Hungarian Treasure are decorated with this type of floral motif—a style particularly popular in the seventeenth century—manifested in textiles, enamel, wood, and, of course, gold and silver objects. The range and impact of this development cannot be overstated: Although these patterns were perhaps particularly popular in Hungary and Germany, their wide circulation and appreciation throughout the guild network is evidenced by examples made as far afield as Norway.

Left to right: Beaker, late 17th century. Hungarian, Rimaszombat. Silver, partly gilded; Overall: 4 1/2 x 4 in. (11.5 x 10.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Salgo Trust for Education, New York, in memory of Nicolas M. Salgo, 2010 (2010.110.50). Hanss Lambrecht III (German, active 1630–70). Tankard, ca. 1660. German, Hamburg. Silver, partly gilded; Height: 8 5/8 in. (21.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Collection of Giovanni P. Morosini, presented by his daughter Giulia, 1932 (32.75.83). Beaker, second half 17th century. Possibly Norwegian. Silver; Height: 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm); Diameter: 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1913 (13.42.18)

At the close of the final act of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Hans Sachs, one of the central characters, encourages Walther to accept an offer to join the revered guild of the Meistersingers, exhorting him to place his unconventional and novel talent within the seemingly antithetical context of the strict regulation of this particularly straight-laced guild. Sachs praises the guild for recognizing this new, fresh talent, while reminding Walther of the importance of tradition and the vital work done by the guild to protect and preserve their craft. He encourages Walther to become a part of this tradition, thereby putting his talent to the service of the entire German people and being part of a larger German artistic heritage, much greater than any individual contribution.

Sachs defines a master of their craft not by any particular set of guild rules or regulations. Anyone, he says, can succeed as an artist in the flush of their youth, inspired by the resplendent beauty of the world, but a true master is one who is able to maintain their talent and create objects of beauty throughout the gamut of life's travails. Wagner paints a picture of guilds as looking both forward and backward—honoring their rich traditions and maintaining a timeworn reputation, while also innovating, remaining on the cutting edge, and inspiring their clients with ever-fashionable and groundbreaking work. Silver objects from Hungary, like those on display in Hungarian Treasure, show how this particular group of craftsmen took advantage of their position in time, mixing tradition with innovation, as well as their geographic location at a crossroads in Europe, invigorating Western forms and motifs with exotic Ottoman influences.

Related Links

Hungarian Treasure: Silver from the Nicolas M. Salgo Collection, on view April 6–October 25, 2015

Read more about Nicolas M. Salgo and the traditions of Hungarian silver in "Nicolas M. Salgo: The Legacy of a Passionate Collector" by Wolfram Koeppe, Marina Kellen French Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and Oliver A. I. Botar, Professor of Art History at the School of Art, University of Manitoba.