Vajra Flaying Knife, ca. 15th century. Tibet. Steel inlaid with gold and silver; L. 22 11/16 in. (57.7 cm); W. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Polsky, 1985 (1985.397)

«Looking closely at historical artifacts is one of the chief privileges and joys of being an art conservator, and I am thrilled to share with you a close look at one of the extraordinary objects currently on view in the exhibition Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas. While this ritual blade is immediately striking in its sinuous form and elaborate decoration, closer examination reveals an inspiring display of technical skill and master artistry.»

The knife's long, single-edged steel blade is set by a short tang into a chiseled and pierced iron-alloy hilt, emerging from the open mouth of a sculpted makara head with a mane of coiled hair. The tongue of this auspicious mythic sea creature extends onto the surface of the blade, where it is engulfed in lavish foliage suggesting abundance, an elaborate image that continues down the top of the blade. The knife is extensively ornamented with silver- and gold-wire overlay damascening, with detail and texture added selectively through delicate chasing and punchwork.

Detail of open-mouthed makara-head hilt leading into foliage on the knife's blade

The magnificent sculpted hilt is formed from solid pieces of iron alloy which have been heated, hammered, and carved to shape. The laborious process of forging, piercing, and carving solid iron elements delivers a powerful sculptural depth of pierced voids and overlapping layers within the vajra and makara head. Elaboration of details and textures, such as the fine circular scales of the makara, is achieved by surface chasing and dapping—a technique in which punches with chiseled or patterned ends are selectively hammered to mark the metal's surface.

Detail of chiseled depth and chased texture in iron alloy of makara-head hilt

From the lush coiled mane of the makara to the delicate budding flowers spilling onto the blade, all of the gold and silver decoration on this knife is created through the wire-overlay damascening process, whereby decorative surface layers of gold or silver are attached to an underlying base metal. A fine pattern of crosshatched lines is cut into the top surface of the base metal, and gold or silver wires are hammered into and adhere to this roughened surface. Once in place, the gold or silver wires are pressed and smoothed to create an even, bright surface. The use of this technique can be determined by noting the crosshatch pattern underneath the overlay damascening visible under magnification in areas of wear.

Microscopic view of wire damascening evident in crosshatching wear pattern (right) and individual wire-hair coils (left), as well as of textured scales imparted through circular punches visible on right

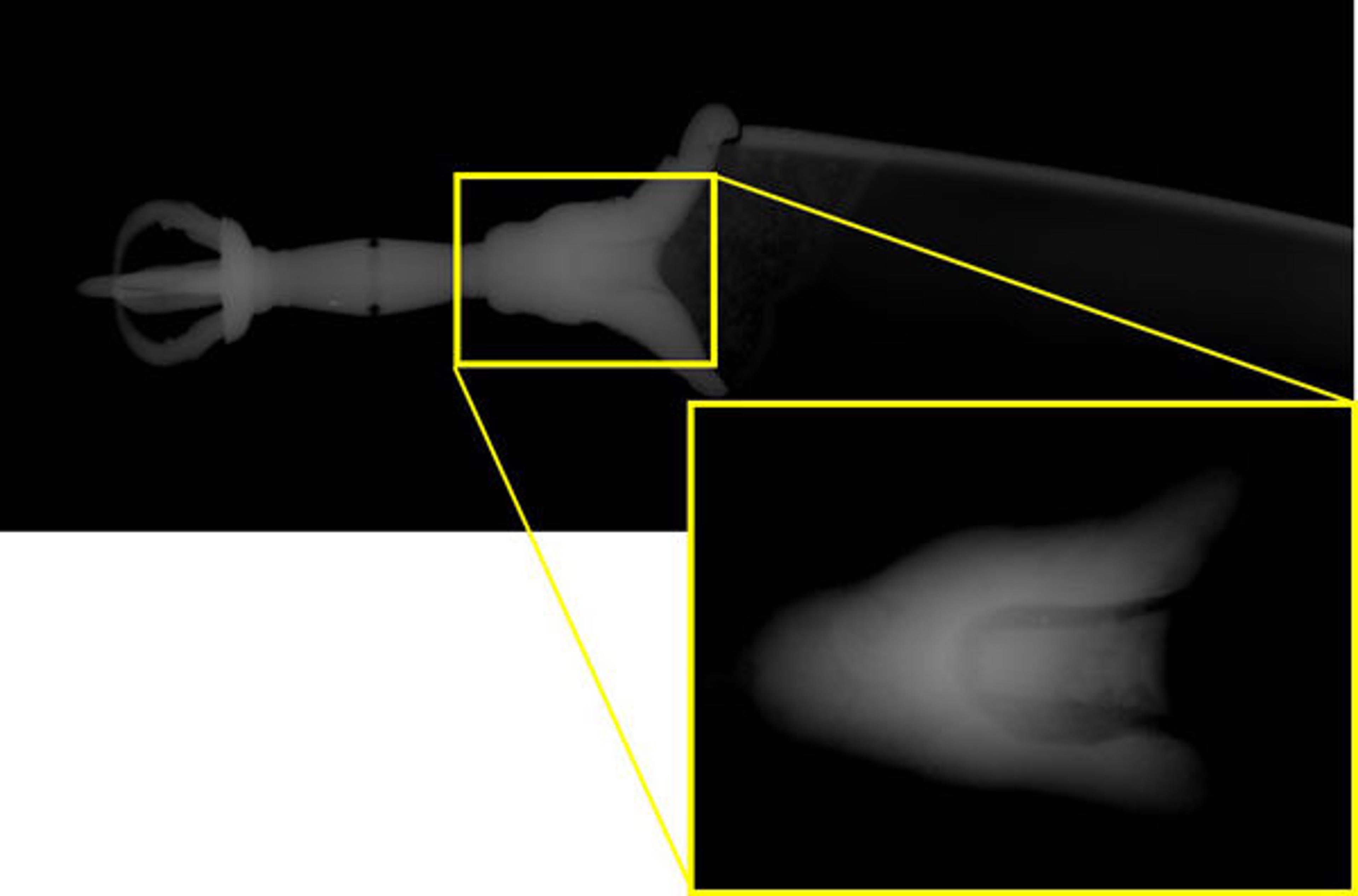

Prior to its installation in the Sacred Traditions exhibition, this blade came to the Department of Objects Conservation because corrosion and tarnishing of the different metals had obscured the skillful construction and beautiful surface embellishment. Before treatment, the piece was closely examined to better understand the material and techniques of its construction in order to assess its condition and stability. Examination in the conservation lab included X-radiography to investigate internal attachment of the blade to the hilt, and ultraviolet illumination to identify the various metals used to adorn the surface. The use of a stereomicroscope provided a magnified view of the knife's construction and allowed for a detailed mapping of its condition. After compiling extensive photographic and written documentation, a plan for treatment was determined that drew on the expertise of various conservators and curators.

X-radiographic detail of blade-tang attachment within hilt

The primary concern was the corrosion of the iron alloys. On the surface of the steel blade, patches of iron corrosion visually disrupted the bare steel and slowly turned the bright metal to rust. On the sculpted hilt, iron alloys functioned as the substrate for the elaborate gold- and silver-damascened decoration. Iron corrosion erupting underneath the noble metal overlays was physically displacing the overlay and covering the gold and silver designs with rust.

Microscopic view of gold-wire damascening lifting due to underlying iron corrosion (top arrow) and of iron-corrosion accumulation over gold damascening (bottom arrow)

Conservation treatment sought to return vibrancy to the knife's appearance while ensuring the preservation of the work's materials and construction. At the same time, the completed restoration work also needed to visually acknowledge the object's age and history.

To begin, surface soil and loose corrosion were reduced using solvents applied carefully on small cotton swabs. Next, working under microscopic magnification, accumulations of iron corrosion overlying the bare blade and damascened surfaces were gently removed using microtools and solvents. This corrosion reduction was performed with painstaking care so as to avoid scratching or dislodging the underlying metals. Over one hundred hours of microscopic work were devoted to the careful reduction of corrosion and tarnish on this knife. Finally, transparent coatings were applied to the metal surfaces to mitigate any future corrosion. These coatings will remain stable over time and can be easily removed in the future, so the object's surface remains unaltered.

Without the burden of corrosion, the beauty and artistry of this stunning object comes to life with renewed vibrancy.

Microscopic view of the pommel's decoration before conservation treatment (above) and after (below)

Photos of the knife pommel before conservation treatment (above) and after (below)

Photos of the knife before conservation treatment (above) and after (below)

View all blog articles related to Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas.

Follow the conversation: #SacredTraditions