Installation view, French Tapestries, on view November 22, 1947–February 29, 1948

«During several visits to the recent exhibition Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry, I marveled at how the artist's inventive compositions guided my eyes through the dramatic, active scenes these artworks portray. The many fantastic details which augment each narrative rewarded repeated viewing and inspired a sense of awe for the unity of effort required to plan and create such massive, intricate images. At times I felt a bit overwhelmed by the immensity of the tapestries—all but one of them loaned from European museums and private collections—and wondered about the tremendous physical labor it must have taken to bring them to New York and install them here at the Metropolitan Museum.»

Curatorial staff in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, who coordinated the exhibition, shared part of this extraordinary story with visitors to the Museum's website on the exhibition's blog. Their experiences last year led me to research in the Museum's archives the Met's first great tapestry exhibition, which occurred nearly seventy years ago.

French Tapestries, on view at the Museum from November 22, 1947, to February 29, 1948, was a display of 138 wall hangings that illustrated the best of French weaving from the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries, together with 62 pieces created during the mid-twentieth century. Included in the exhibition were exceptional examples made in the renowned factories of Gobelins and Beauvais, a stunning sequence of panels from the Apocalypse series from the Museum of Tapestries at Angers, the six-tapestry Lady with a Unicorn series from the Cluny Museum, several modern works by artist Jean Lurçat, and even a 1946 piece designed by Henri Matisse titled Polynesia, the Sky. The unprecedented U.S. showing of such masterworks drew more than 140,000 visitors and was warmly praised by art critics and the press. A New York Times reviewer urged his readers to visit the show multiple times:

The collection . . . is so magnificent that it is difficult to discuss the event with restraint . . . This is not an exhibition to be taken in even superficially at one visit . . . Here in one display are collected priceless works which, if one were to go to France, would require weeks if not months of travel to see piecemeal in churches, cathedrals, museums and other collections. (New York Times, November 23, 1947)

Installation view, French Tapestries

Remarkably, this massive exhibition was installed in twenty-four galleries at the Metropolitan little more than a year after its conception. In the summer of 1946 the Louvre had organized a large Paris exhibition of the finest French tapestries then held in both public and private collections. Soon after, a selection of pieces from that show traveled to Amsterdam, Brussels, and London, an early indication of the significant role that cultural diplomacy would play in French foreign affairs during the postwar era. The idea to bring a version of this exhibition to the U.S. originated around the same time, through conversations between American museum leaders and George Salles, director of the Museums of France, who visited New York that year.

In January 1947, Metropolitan Museum Director Francis Henry Taylor followed up with a written proposal to the French government, transmitted through the French ambassador to the United States, Henri Bonnet. "The entire north wing of the Museum building, consisting of some twenty galleries, will be devoted to it," promised Taylor. He enclosed a wish list of tapestries, stressing that "the Apocalypse series from Angers and the Licorne series from the Cluny Museum . . . are considered essential."

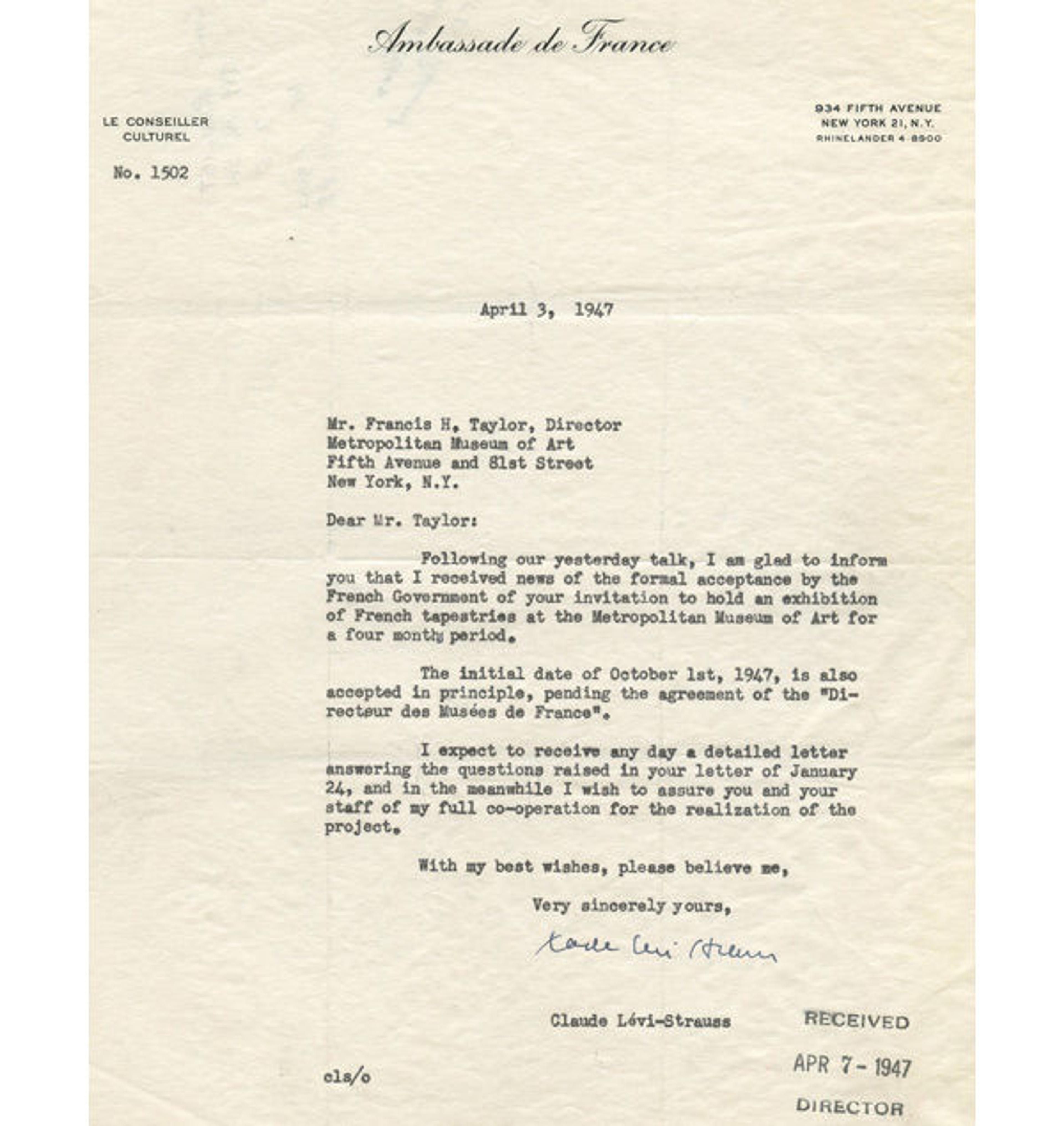

Letter, Claude Levi-Strauss to Francis Henry Taylor, April 3, 1947. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

The French reply was delivered, via a surprising cameo, by the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who then lived in New York and taught at the New School for Social Research while also serving on the staff of the French Consulate. In the latter capacity he met and corresponded with Taylor in the spring of 1946, and was first to share with him the good news "of the formal acceptance by the French Government of your invitation to hold an exhibition of French tapestries . . ."

Soon after, Henri Bonnet delivered an agreement that assigned the Met with responsibility to pay for advertising and a catalogue, while the Association Francaise d'Action Artistique would coordinate transportation of the artwork from Paris to New York. Bonnet also informed the Metropolitan that Pierre Verlet, curator in chief of the Department of Decorative Arts at the Louvre, would develop a display sequence and installation plan, and would travel to New York to oversee preparations in collaboration with Met staff. Levi-Strauss separately confirmed a rather significant detail—that French President Vincent Auriol had approved the use of a French warship to transport the tapestries to America.

Verlet traveled to New York in May to see the proposed exhibition space, to discuss possible gallery arrangements of the tapestries, and to review the budget. Inevitably, there were disagreements over costs, and as the weeks flew by, the French grew impatient with the minor revisions proposed by Taylor's staff. "We have prepared this exhibition on the grand scale for New York for it is there and in your museum that we are counting above all on presenting it," implored Salles in July.

The Museum eventually accepted detailed advice from Verlet and Salles regarding money-saving installation methods implemented in Europe—in particular, the use of "tubular framework" scaffolding to mount portions of the show—that would preserve the integrity of the curatorial vision. "It now seems possible to keep precisely to Verlet's original selection allotment of space and arrangement of exhibition," telegrammed Metropolitan staff member Horace Jayne to Salles at the end of July. The basic plan for the New York presentation of French tapestries was settled, though haggling over insurance costs continued for several more weeks.

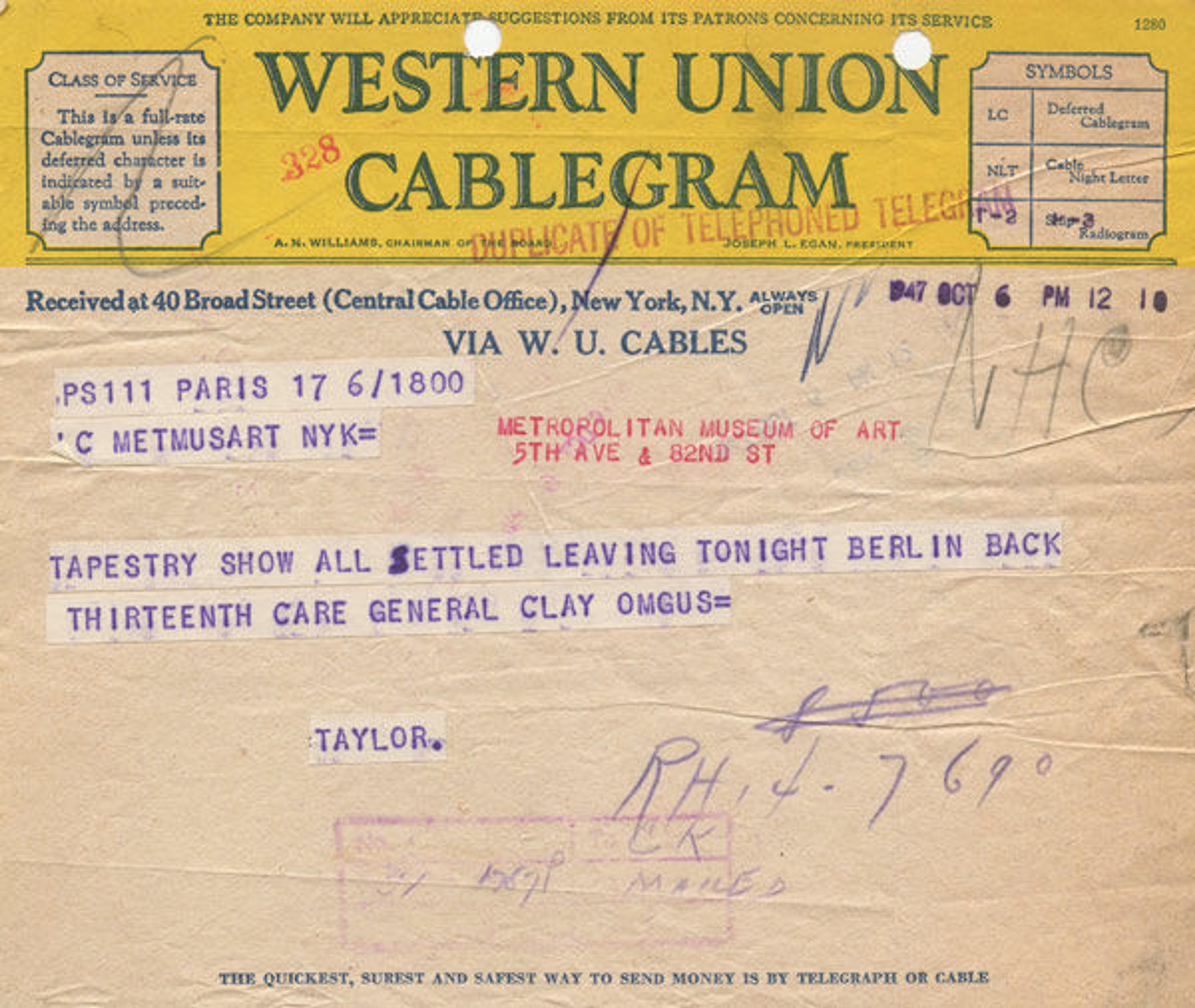

Cablegram, Francis Henry Taylor to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 6, 1947. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

During September and October, Francis Henry Taylor traveled in Europe with Met Curator Theodore Rousseau, and the pair were able to finalize several remaining details. Back in New York, the Museum issued a press release announcing the exhibition schedule, with a private opening slated for Friday, November 21, followed by a public opening the next morning. It was also reported that staff were "clearing twenty-four galleries in the second floor of the North Wing" to make way for the show. Museum workers were by this time well-seasoned in the intricacies of special-exhibition installation, because the Metropolitan had hosted several other loan shows during the World War II years, when much of its permanent collection was stored outside of New York for safekeeping. Also by this time, the editing and production of an associated sixty-page illustrated catalogue was well underway. The next significant task to accomplish was the transport of the tapestries.

French cruiser Georges Leygues in the 1940s, U.S. Navy All Hands magazine, January 1948, 13. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons

The vessel assigned to carry this precious cargo to New York was the Georges Leygues, a cruiser named for a politician who had briefly served as French prime minister during the 1920s. This ship had played an active role during the war, including support for the June 1944 Allied landing at Normandy. She departed on October 21 from Toulon, where Theodore Rousseau served as the Met's representative at the embarkation ceremony.

Georges Leygues crossed the Atlantic with more than just an irreplaceable collection of tapestries. Also in her hold was a shipment of French gold, valued at more than eighty million dollars, to be exchanged with the U.S. Treasury for cash needed to purchase commodities in short supply in postwar Europe. In addition, she carried a collection of paintings and drawings by French marine artists including Luc-Marie Bayle and Herve Baille, which were later displayed at the Associated American Artists Gallery on Fifth Avenue. Happily, the Georges Leygues made a safe passage and arrived in New York on November 1, and was docked at Hudson River Pier 26 near the foot of Canal Street.

At the disembarkation ceremony Henri Bonnet formally turned over the art cargo to New York Mayor William O'Dwyer, who noted: "While the countries of the world are thinking in terms of war, France is thinking in terms of culture." The president of the Met's Board of Trustees, Roland L. Redmond, then accepted the tapestries on behalf of the Museum. Director Francis Henry Taylor was present, as was exhibition curator Pierre Verlet's young son, Bruno, who was that year attending school in Philadelphia.

Soon after the ceremony, three trucks with a police escort moved the tapestries—packed in forty-four crates—uptown to the Metropolitan. A few days later Roland Redmond ordered the delivery of a gift-wrapped pound of chocolate to each of the six hundred crew members of Georges Leygues. On November 6, a large contingent of the ship's sailors and officers, including her captain, Jacques Willaume, marched up Broadway from the Battery to City Hall for another celebration of her safe arrival.

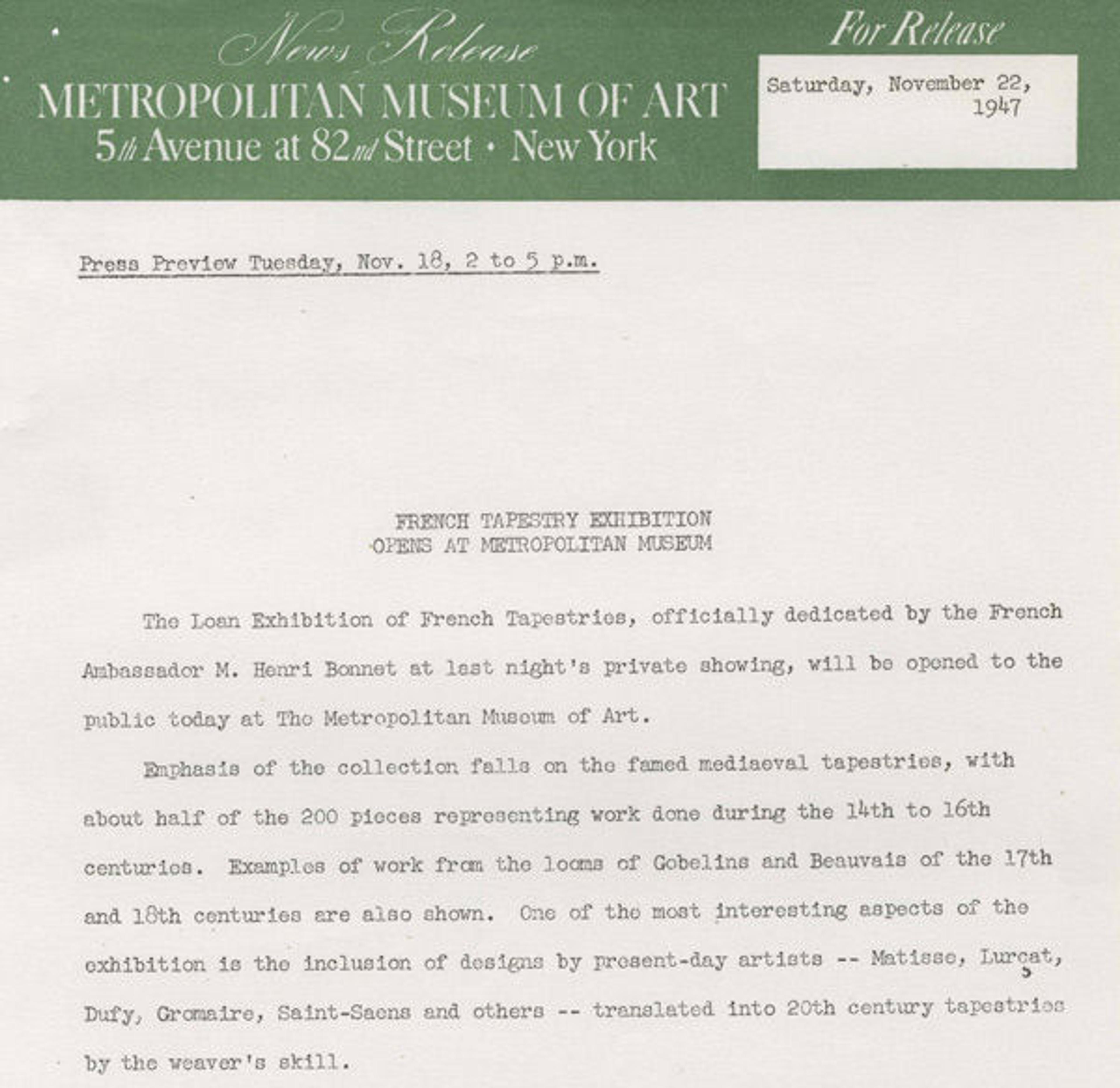

French Tapestries opening-day press release, November 22, 1947. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Over the next few weeks there was a flurry of activity at the Museum's north end as the tapestries were installed to Verlet's precise specifications. Many of these galleries normally housed objects from the Museum's collections of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern art; all of these were carefully packed and moved to storage for the duration of the exhibition.

The Metropolitan held its grand preview of French Tapestries on the evening of Friday, November 21, 1947. Eight thousand people attended, including Museum trustees and staff, city officials, and representatives of the French diplomatic corps and cultural community in New York. Redmond, Taylor, and Verlet addressed the gathering from the Museum's Great Hall balcony, and their remarks were broadcast on speakers positioned around the galleries. French Tapestries officially opened to the public the next morning, and more than ten thousand visitors passed through the galleries during the show's first week.

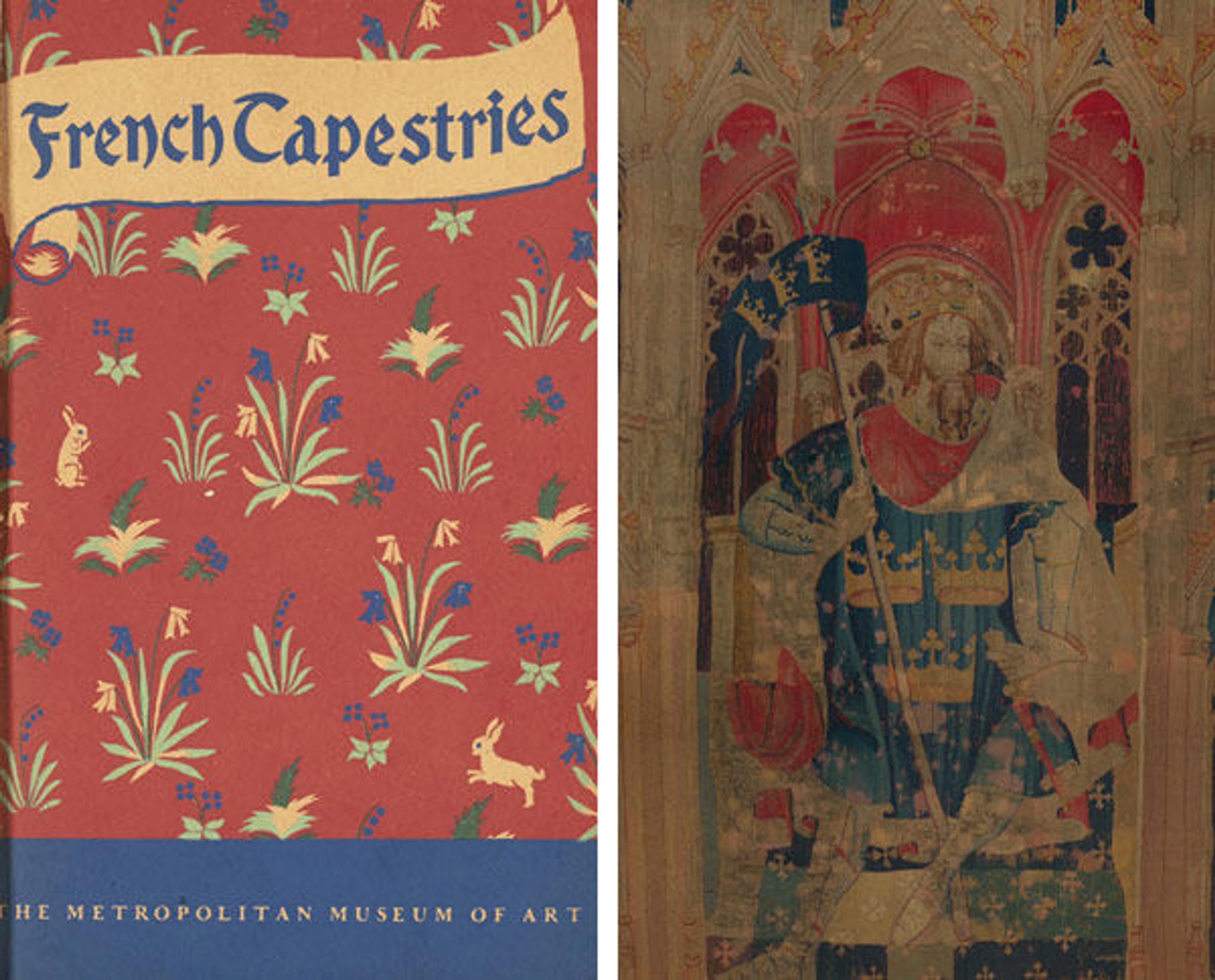

Left: Cover, French Tapestries exhibition catalogue. Right: "King Arthur and Two Attendants" (from the Nine Heroes Tapestries) (detail), ca. 1400. South Netherlandish. Wool warp, wool wefts. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Munsey Fund, 1932 (32.130.3a, b)

The unprecedented gathering of so many examples of fine European tapestries in one place inspired the Museum's curatorial staff to undertake fresh research on the Met's own holdings. Curator of Medieval art, and later Museum director, James Rorimer penned an essay for the Museum's November 1947 Bulletin that highlighted characteristics shared between several of the loaned Gothic-period tapestries and examples owned by the Met. At the time, gallery A16–17 was regularly used to display the Met's tapestry holdings. In conjunction with French Tapestries, the Museum's King Arthur panel (above) was specially installed there to encourage comparison with the French Angers series. The buzz generated by the exhibition also promoted new interest in the medium outside of the Museum; art dealers Duveen Brothers and French & Co. both installed in their galleries displays of tapestries from their stock during the exhibition's run.

French Tapestries closed on February 29, 1948. Over the next few days, all two hundred pieces were carefully taken down, repacked in shipping crates, and prepared for their next journey—an overland trip to the Art Institute of Chicago, where a selection of the objects were presented from March until May. They returned safely to France after the Chicago display.

Summarizing the views of his colleagues at the Metropolitan in a post-exhibition letter to the French Embassy, Francis Henry Taylor wrote: "We felt that the exhibition from every point of view was a most distinguished and successful venture. During my eight years at the Metropolitan I have never seen such a good audience." Taylor also alluded to the political significance of the show in the post–World War II era by suggesting that "there has never been an exhibition in this country that was more appreciated in the circles which the French Government is trying to reach." From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, French Tapestries appears as a landmark episode in cultural history—a story of skillful diplomacy, herculean effort, public acclaim, and a safe passage home that was itself worthy of being commemorated in a tapestry.

Related Links

#Tapestry Tuesday posts on Met Blogs

Join the conversation: #TapestryTuesday