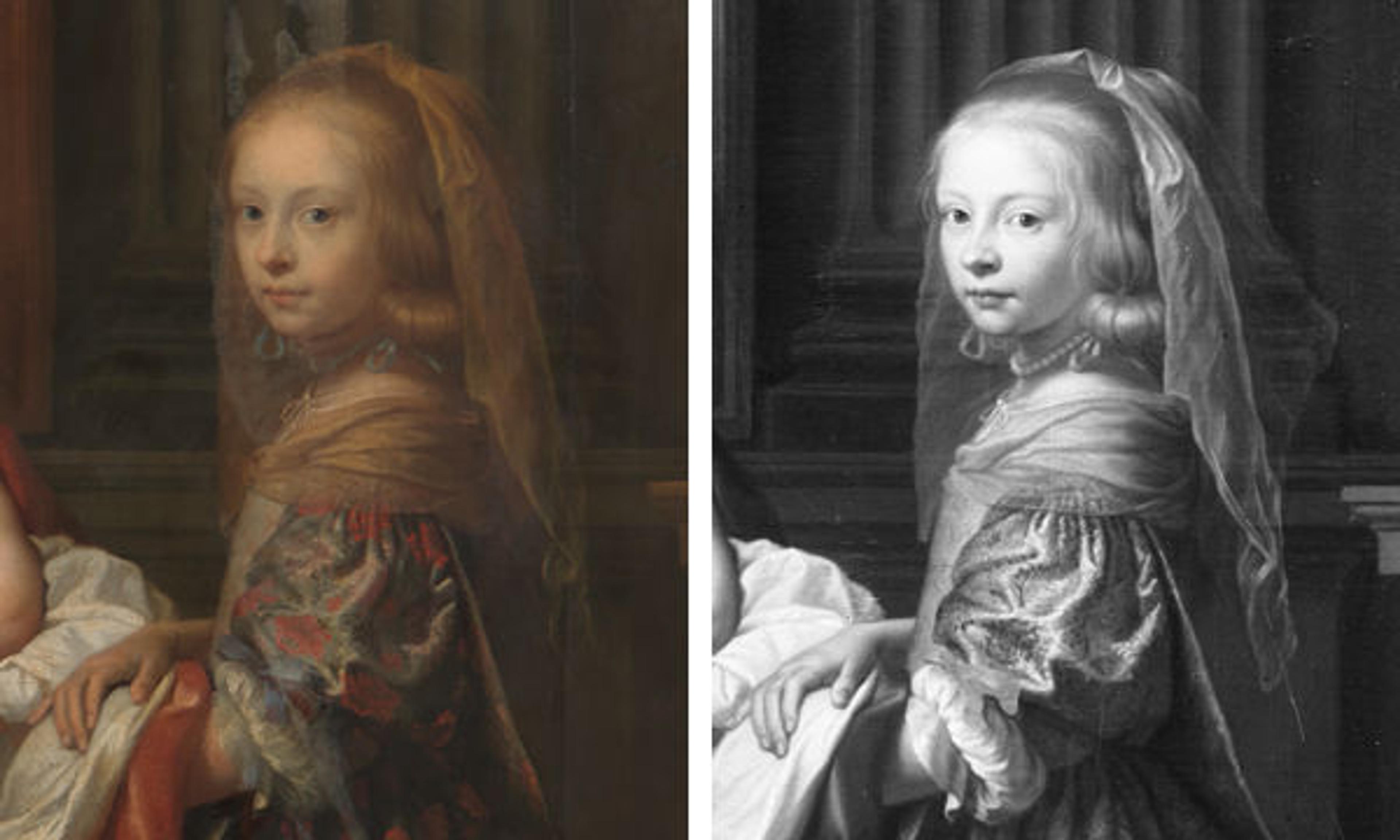

Left: Charles Le Brun (French, 1619–1690). Everhard Jabach (1618–1695) and His Family, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 110 1/4 x 129 1/8 in. (280 x 328 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 2014 (2014.250). Right: Charles Le Brun (French, 1619–1690). Everhard Jabach (1618–1695) and His Family. Formerly Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Berlin (destroyed in World War II)

«Well, if you live in New York and work at the Metropolitan Museum, there's really only one acceptable answer to that question! But what happens when two versions of a picture exist, as is the case with the Metropolitan's new painting by Charles Le Brun of the German banker Everhard Jabach (1618–1695)? I worried about this as we entered into negotiations for the purchase of the picture.»

Normally, the best way to resolve such a question is to examine both paintings and come to some conclusion about the superiority of one over the other. But there was a complication: in this case the other version, which belonged to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, was destroyed in World War II. Fortunately, the glass negative of a black-and-white photograph of it survived.

Charles Le Brun (French, 1619–1690). Everhard Jabach (1618–1695) and His Family. Formerly Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Berlin (destroyed in World War II)

As in any pulp detective story, we began by assembling the known facts about each picture. Our findings are summarized in the work's catalogue entry, which you can find on the painting's object record. It turns out that one version—the one the Metropolitan has acquired—was painted for Jabach himself. It hung in his grand mansion in Paris and was moved to the family house in Cologne following his death. The other version was evidently intended for his brother-in-law and was sent back to his wife's family house, also in Cologne. Obviously, the one for Jabach must have come first and was the superior version, right? Not so fast.

There are differences between the two paintings, and if you compare the images of each, you'll see quite clearly that a different bust of Minerva—the ochre-colored piece of sculpture that presides over the other assorted objects in the stunning still life—is shown in each painting. The arrangement of the books is also different. And there are other, less immediately obvious differences that you can find for yourself.

The bust of Minerva and arrangement of books at its base differ between the Met's painting (at left, before conservation) and the Berlin version (now destroyed).

So the two pictures were variants, not exact replicas, of each other. Very intriguing. But what about their respective quality? At this point in our investigation, I turned to my colleagues in Berlin in an effort to get a better image of the Berlin painting than was otherwise available. They kindly scanned the glass negative of the destroyed painting and sent the high-resolution image that you now see above.

Note how eleven-year-old Anna Maria's alert but poised attitude in the Met's painting (at left, before conservation) becomes somewhat bland in the destroyed version in Berlin.

If you make the same comparisons between the two works that I did, I think you'll agree that the quality of the Berlin painting is vastly inferior: the figures have a smooth, almost airbrushed quality and lack the expressive liveliness of those in the Metropolitan's version. No wonder that in the eighteenth century, the Metropolitan's painting became a principal sight in Cologne—it's noted in guidebooks to the city and was seen by the great poet-philosopher Goethe as well as by the British painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. In contrast, the Berlin version was reputed to have been painted in part by the workshop.

But this is not the end of the story. As the cleaning of the Metropolitan's painting has proceeded, the relationship of the two pictures and the order in which they were painted has become more and more intriguing. But that's for another time.