Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Twenty-First Century

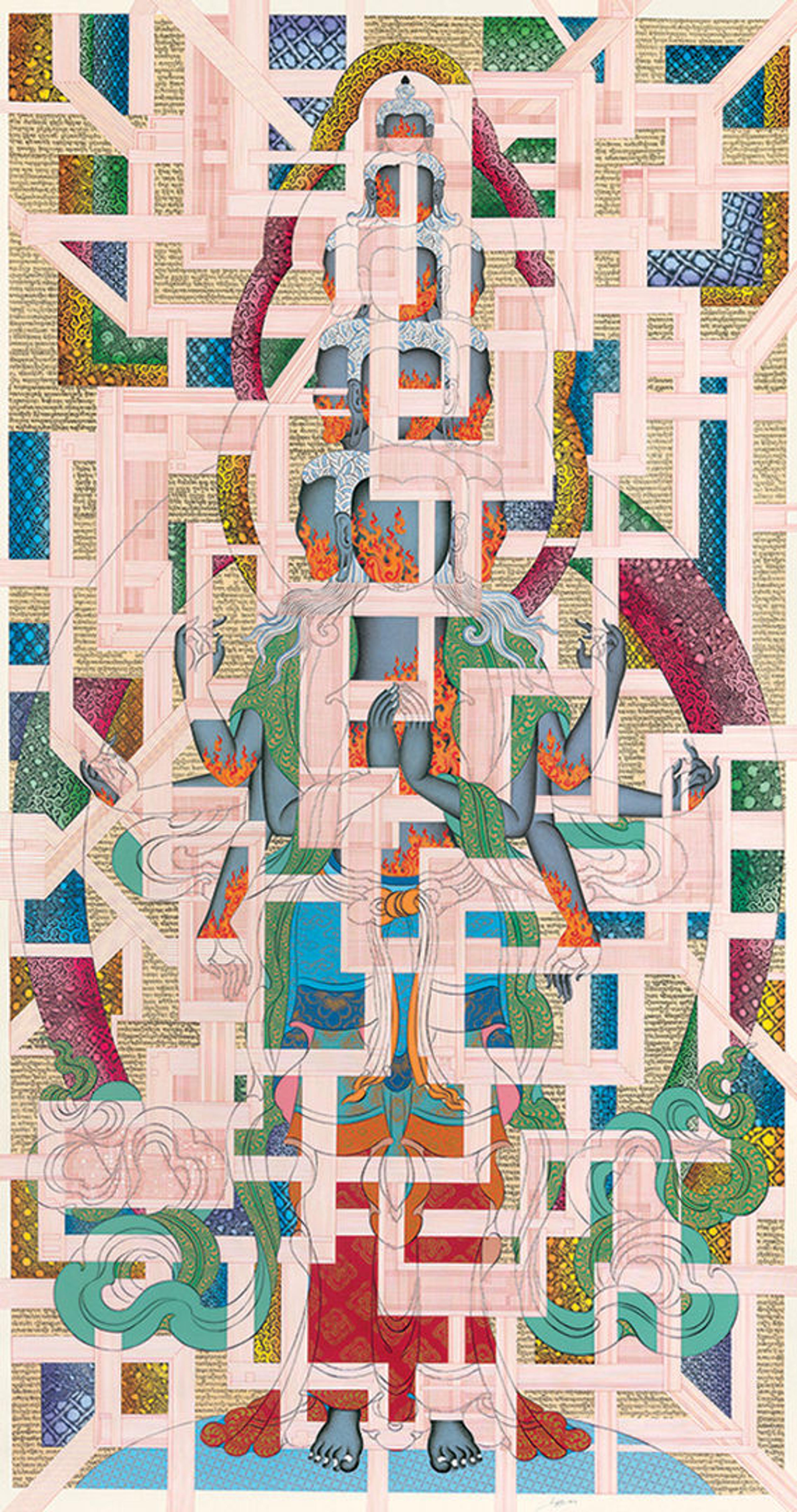

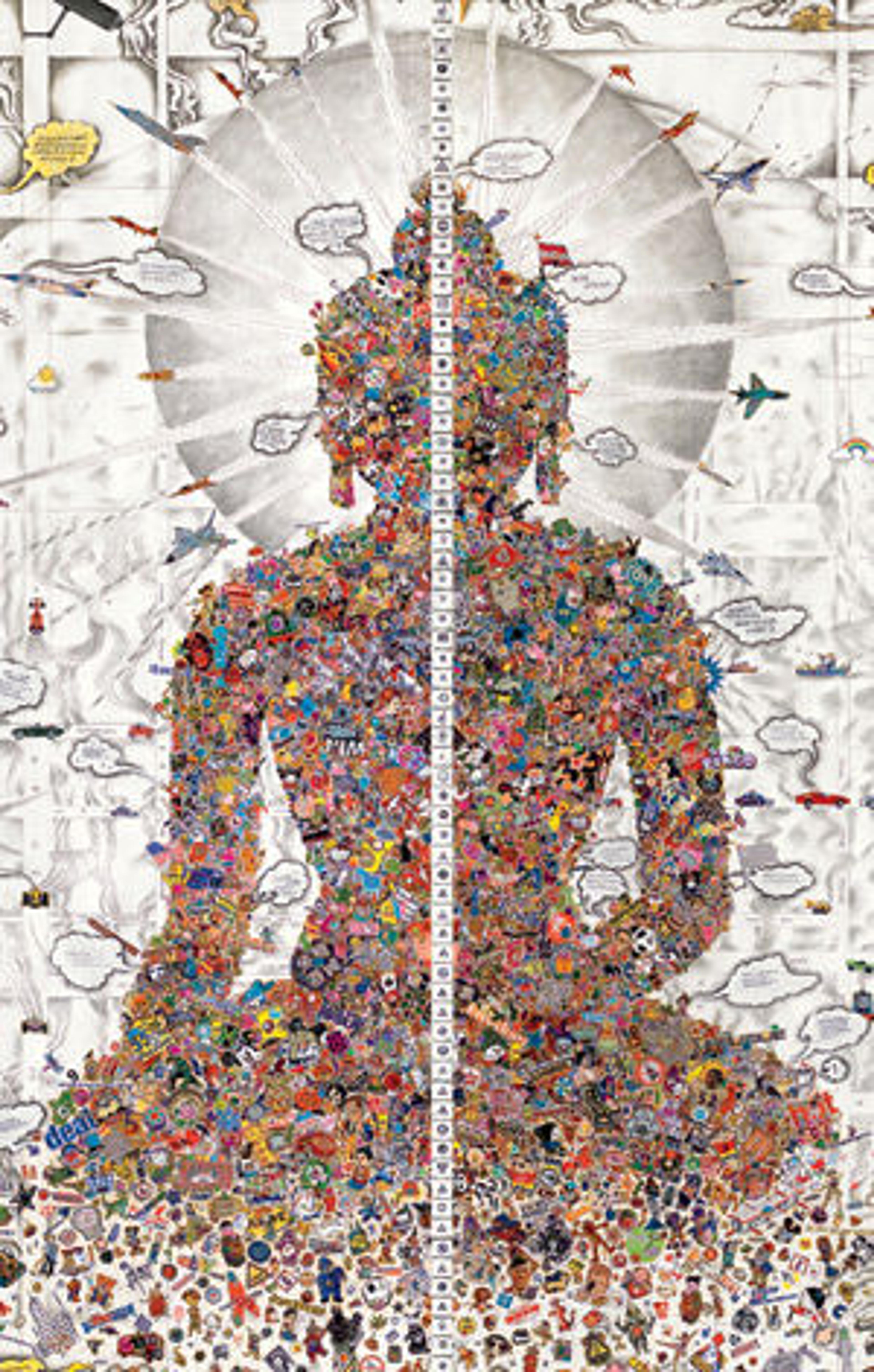

Tenzing Rigdol (born Kathmandu 1982). Pin Drop Silence: Eleven-Headed Avalokitesvara, 2013. Ink, pencil, acrylic, and pastel on paper; image: 91 5/8 x 49 1/8 in. (232.7 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Andrew Cohen, in honor of Tenzing Rigdol and Fabio Rossi, 2013 (2013.627)

«A rapidly evolving contemporary art movement has emerged both in Tibet and across the world in conjunction with the Tibetan diaspora, offering a wide range of perspectives on Buddhism and modern Buddhist practice. Two contemporary Tibetan artists currently featured in the exhibition Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations, Tenzing Rigdol and Gonkar Gyatso, both address Buddhist themes, but their intended audiences are global in scope, and their works are primarily vehicles of artistic expression and vision rather than objects of devotion. Nonetheless, merely presenting a Buddha or bodhisattva in a work of art charges it with a certain meaning, regardless of artistic intent. Buddhist ideas, traditional texts, and the current monastic tradition ground these images historically in a religious context, even if a contemporary viewer might not necessarily read them as "Buddhist art."»

Tenzing Rigdol's figure of Avalokiteshvara stands within a radiant mandorla, burning with the light of his enlightenment or nonexistence, while his eleven heads comment on many realms of knowledge and simultaneous realization.

Because the deity's face has been omitted, the viewer is denied any direct or emotionally charged devotional contact with this divine being, as eye contact is seen as the primary means of accessing the divine in this manner. By omitting the eyes, Tenzing has effectively taken the image out of a devotional context, forcing the viewer to consider it as an independent work of art—the creation of an individual.

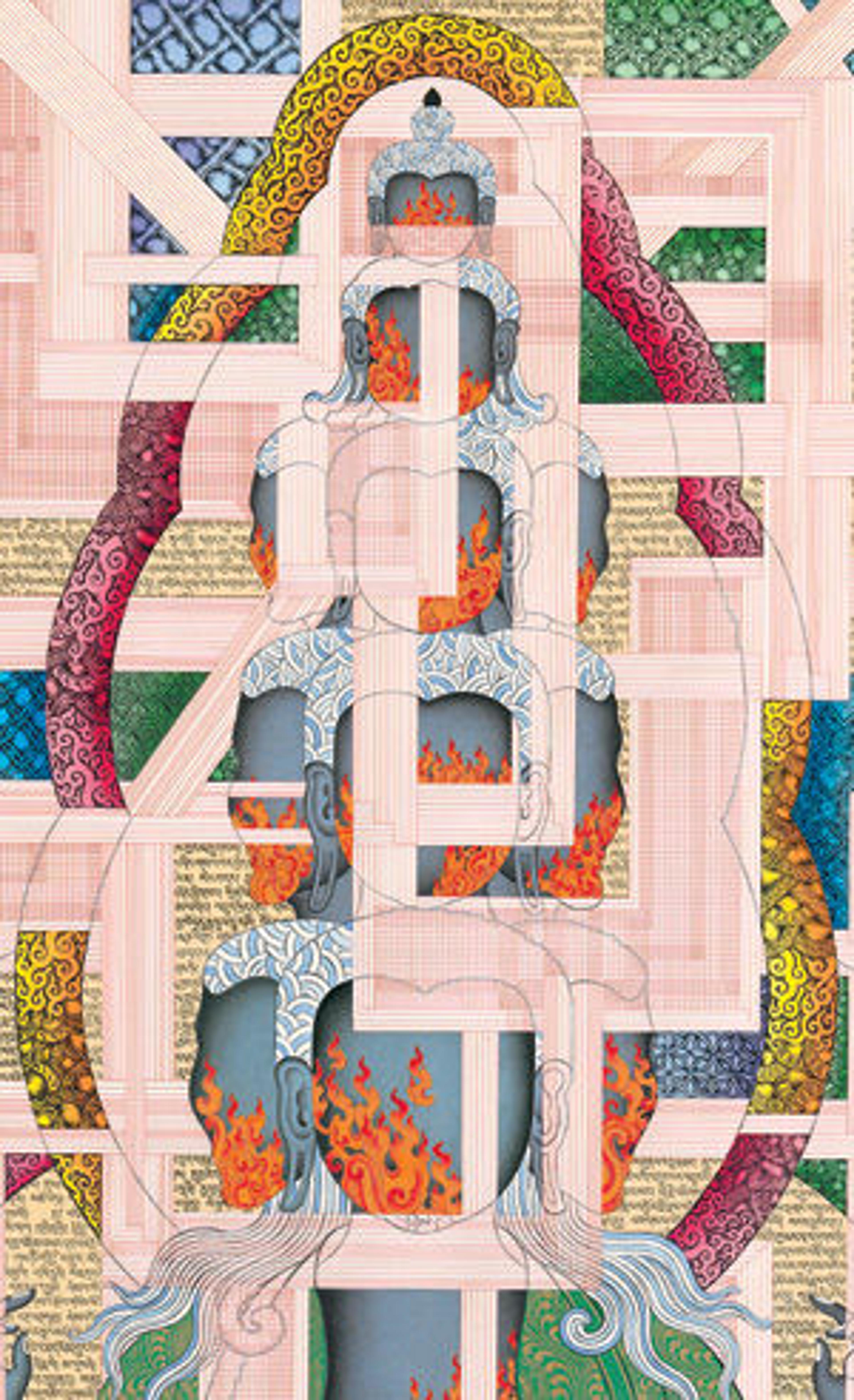

Since the seventeenth century, this type of deity has typically been shown in Tibetan paintings amid blue-green mountains, a mode of representation that comes out of the Chinese landscape tradition. Tenzing has instead fractured the traditional space and recontextualized Avalokiteshvara's place within it; his linear architecture creates zones filled with text and areas of vibrantly colored patterns. When asked about the grid of lines that unifies the figure and the faceted background space, Tenzing explained that he is trying to reveal the compassionate, human quality of Tibetan Buddhism through traditional means by showing the proportional structures that are part of the preparatory drawing for all tangka paintings, but usually hidden beneath the finished paint layer. Underlying the image's potency is Tenzing's personal iconography, which playfully relates to that of the established Buddhist tradition—in particular the transformed and abstracted human figure of Avalokiteshvara, without being either literal or reductive. The painting's charged layers of meaning can thus be openly interpreted by diverse audiences.

Tenzing Rigdol (born Kathmandu 1982). Pin Drop Silence: Eleven-Headed Avalokitesvara (detail), 2013. Ink, pencil, acrylic, and pastel on paper; image: 91 5/8 x 49 1/8 in. (232.7 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Andrew Cohen, in honor of Tenzing Rigdol and Fabio Rossi, 2013 (2013.627)

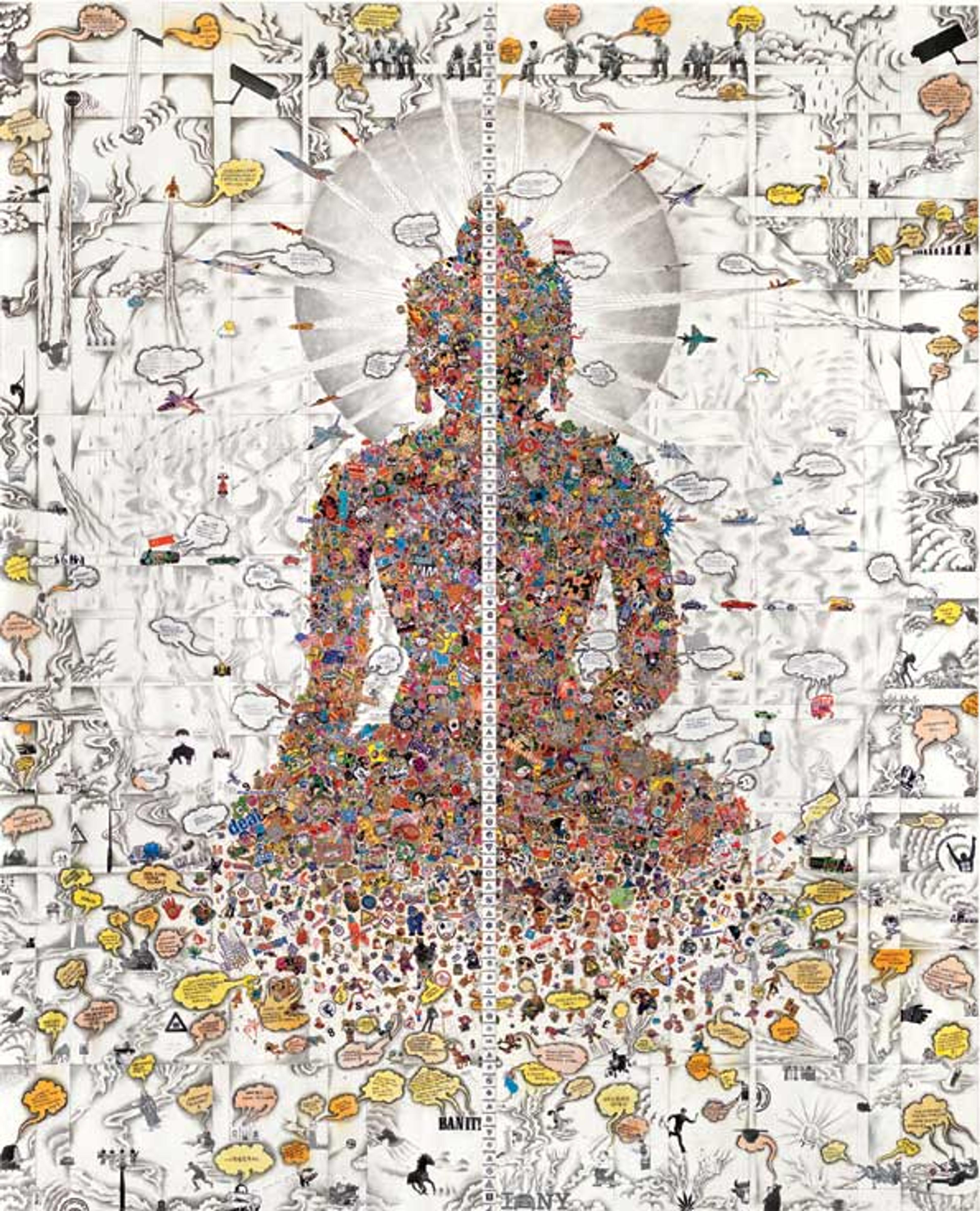

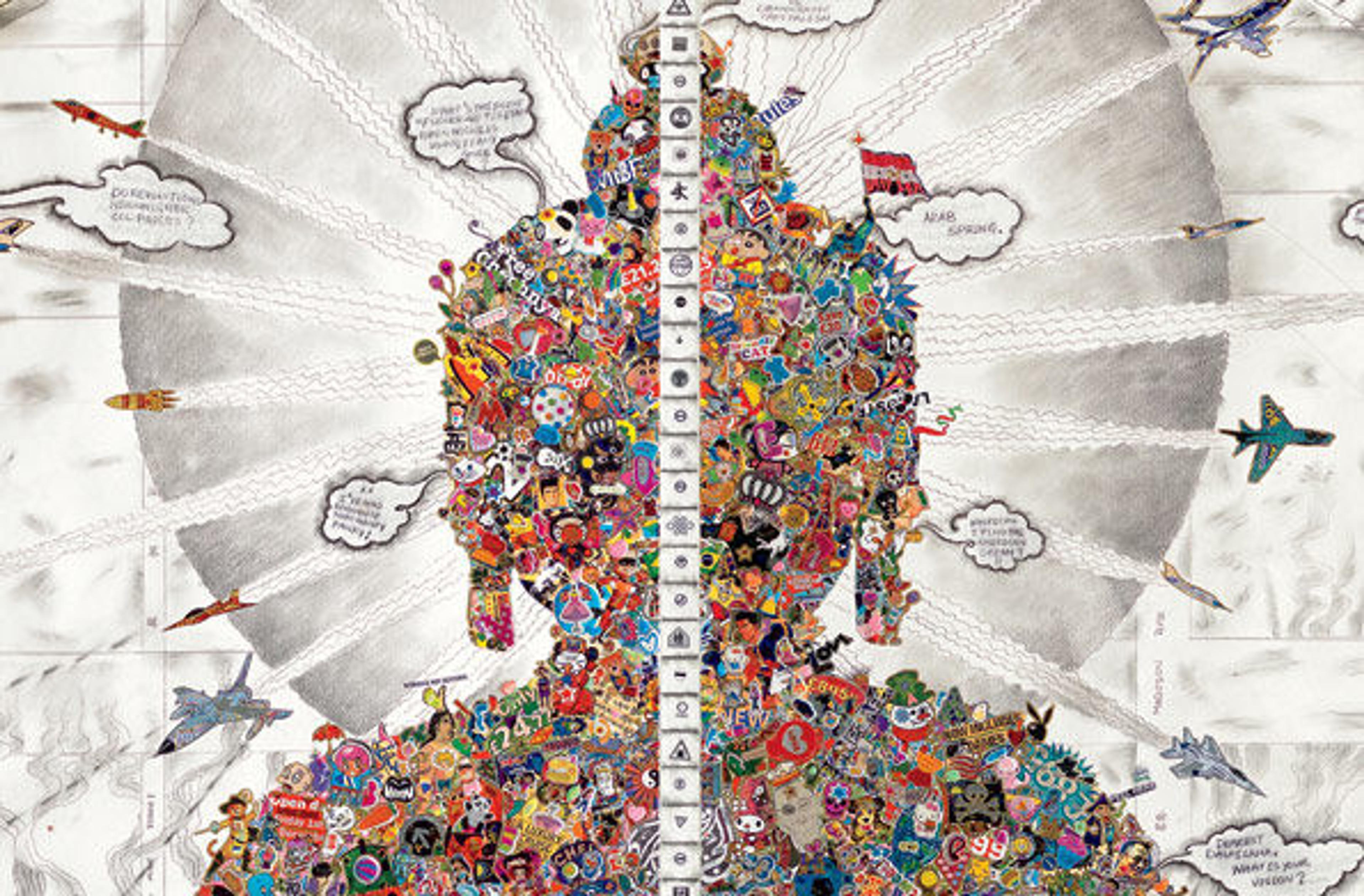

Gonkar Gyatso (born Lhasa 1961). Dissected Buddha, 2011. Collage, stickers, pencil and colored pencil, and acrylic on paper; 9 ft. 2 1/4 in. x 90 1/2 in. (280 x 229.9 cm). Promised Gift of Margaret Scott and David Teplitzky. © Gonkar Gyatso

Gonkar Gyatso's massive collage, Dissected Buddha, could not be more different from Tenzing's Avalokiteshvara in terms of conception and facture, but he, too, tempts the modern viewer by initially showing us what we might expect from a "Buddhist" image: in this case, the Buddha reaching down to touch the earth at the moment of his enlightenment, following long-established models.

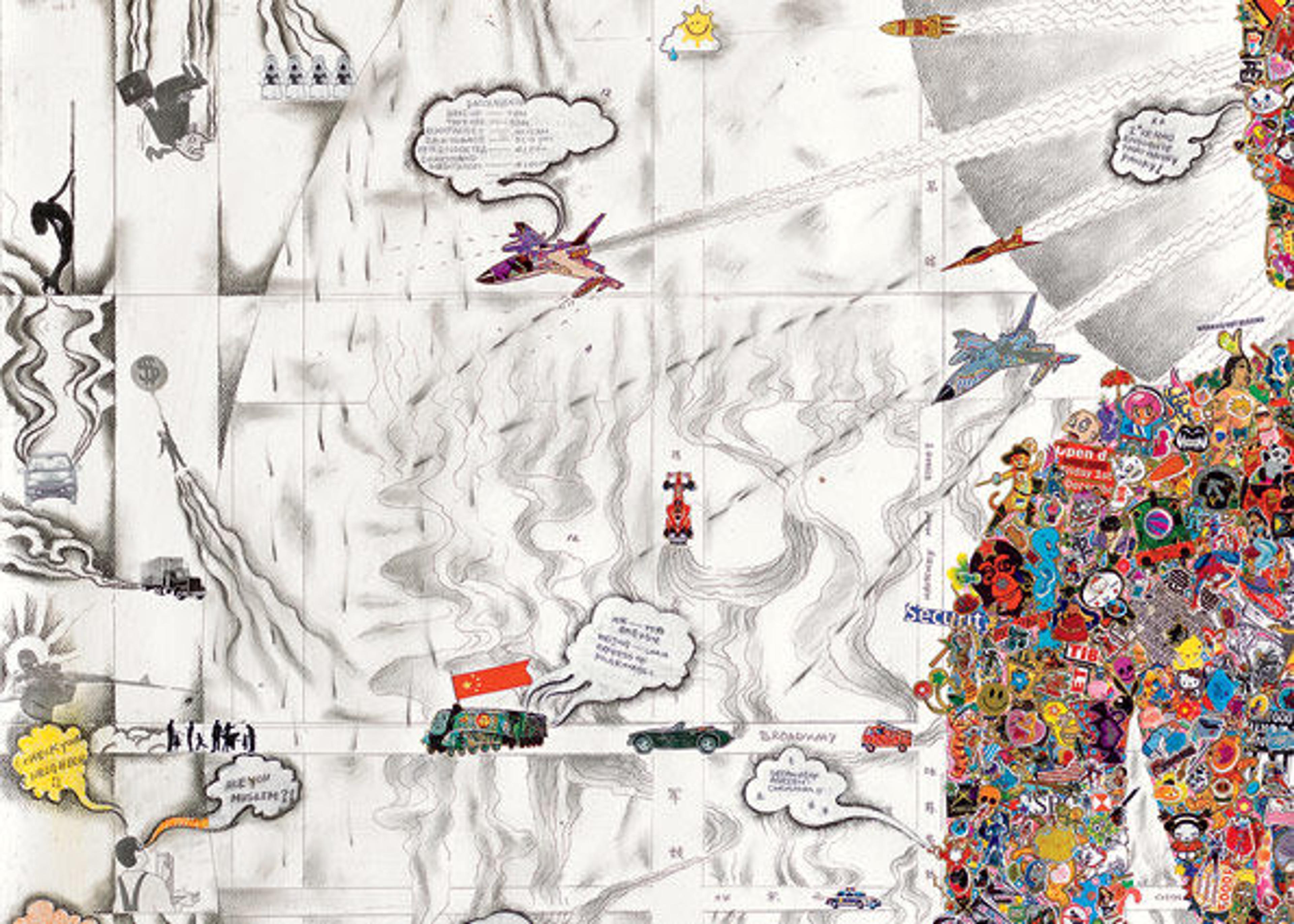

Gonkar Gyatso (born Lhasa 1961). Dissected Buddha (detail), 2011. Collage, stickers, pencil and colored pencil, and acrylic on paper; 9 ft. 2 1/4 in. x 90 1/2 in. (280 x 229.9 cm). Promised Gift of Margaret Scott and David Teplitzky. © Gonkar Gyatso

The grid of streets into which the Buddha is set quickly transmogrifies, however, into an architectural framework teeming with airplanes, rockets, and other vehicles traveling out from and across his halo. The Buddha's body, meanwhile, dissolves into a cacophony of stickers and blurbs, many of them irreverent comments on the state of the world. From a purely Buddhist standpoint, the figures surrounding the Buddha could reference the attack of Mara—ruler of the realm of illusion and the endless cycle of rebirth—who, at the moment of enlightenment, sent his army to stop the Buddha by tempting him with material desires, lust, and passions, all of which ultimately took the form of violence. In this climactic moment, the Buddha touched the earth, recalling his many past meritorious actions, thereby vanquishing Mara's army and attaining enlightenment.

Left: Gonkar Gyatso (born Lhasa 1961). Dissected Buddha (detail), 2011. Collage, stickers, pencil and colored pencil, and acrylic on paper; 9 ft. 2 1/4 in. x 90 1/2 in. (280 x 229.9 cm). Promised Gift of Margaret Scott and David Teplitzky. © Gonkar Gyatso

One could also argue that Dissected Buddha addresses how technology and mass-produced pop culture impair our ability to apprehend the Buddha's enlightened form. This perspective offers a frame for understanding the fractured collage that makes up the Buddha's figure, with its candy-colored stickers and visually appealing cartoon characters, consumer goods, and sinister political figures. The bright, textually dense mass touches upon many diverse, easily dissected aspects of everyday life, including the ubiquitous mass marketing heaped upon us by the Internet. In the end, we may appreciate this imagery, in part, because it entertains us and delivers the same products and ideas that drive today's global society.

The mass defies comprehension, but one is seductively drawn in all the same and rewarded with a rich tapestry of familiar forms—a collage of whimsical texts and captions questioning the political status quo. The swarm of minutiae demands (and deserves) the viewer's careful attention, but in the process it rapidly distracts from the whole. This is the key to Gonkar's work: making us experience losing sight of the Buddha amid the irrelevant but glittering fragments of mass-produced consumer media.

Gonkar Gyatso (born Lhasa 1961). Dissected Buddha (detail), 2011. Collage, stickers, pencil and colored pencil, and acrylic on paper; 9 ft. 2 1/4 in. x 90 1/2 in. (280 x 229.9 cm). Promised Gift of Margaret Scott and David Teplitzky. © Gonkar Gyatso

Although Gonkar addresses issues relevant to Tibet, his outlook is both culturally and linguistically complex, and truly international. With respect to the image of the Buddha, a central motif of Gonkar's work for the past twenty years, the artist questions its meaning as a symbol of enlightenment in the twenty-first century. "An artist should be free to use the form of the Buddha like a canvas," he says. "Just because it is in the shape of the Buddha does not make it the Buddha." While this kind of statement could be construed as a threat to tradition, it is philosophically grounded in the longstanding idea that the image of the Buddha is nothing more than a mental projection, without inherent reality. As Gonkar puts it, "When is the Buddha not the Buddha?"

Related Link

Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations

Kurt Behrendt

Kurt Behrendt is an associate curator in the Department of Asian Art.