Introducing #tapestrytuesday

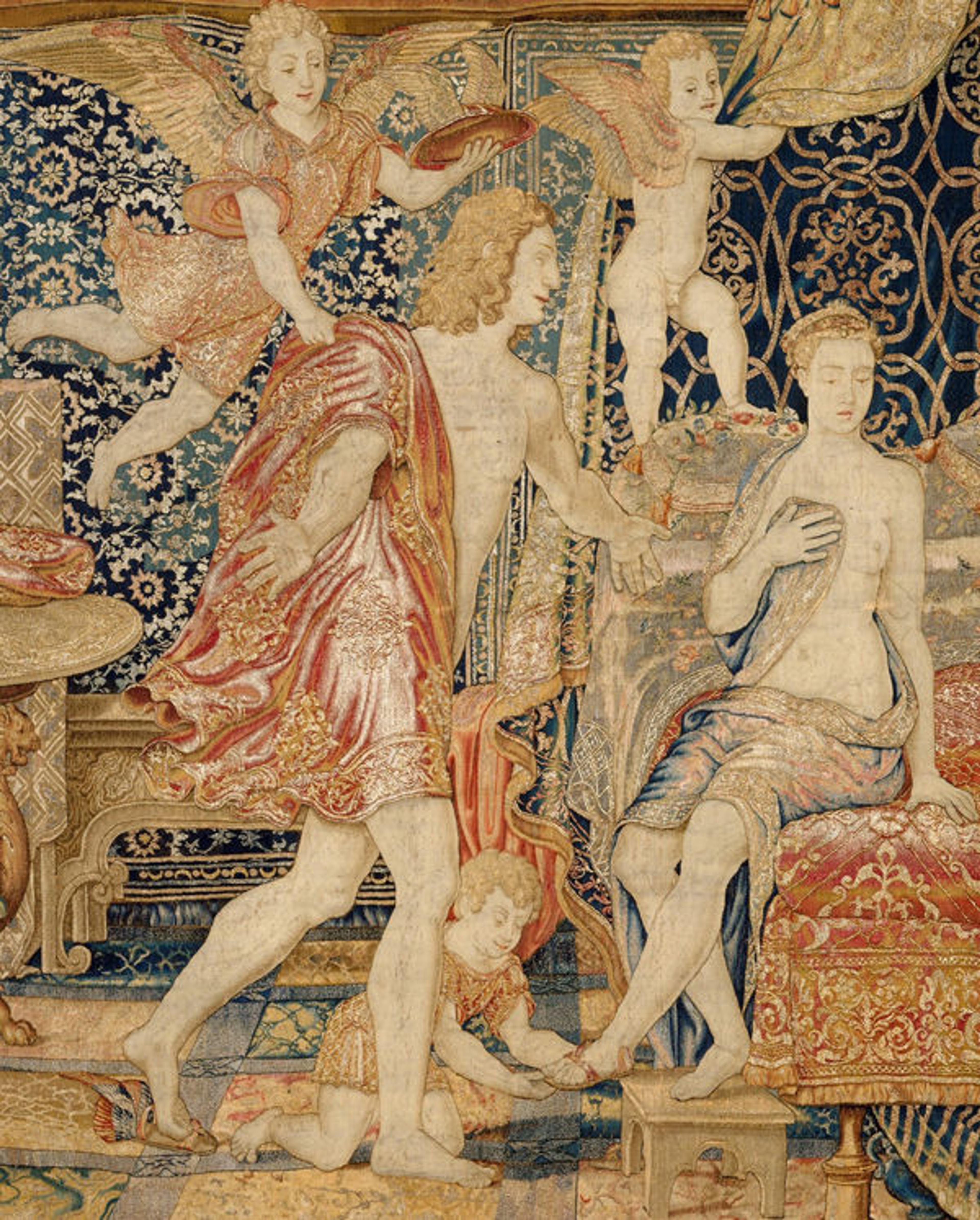

The Bridal Chamber of Herse, from a set of eight tapestries depicting the Story of Mercury and Herse (detail), ca. 1550. Design attributed to Giovanni Battista Lodi da Cremona (Italian, active 1540–52). Weaving workshop directed by Willem de Pannemaker (Flemish, active Brussels, 1535–78, died 1581). Flemish. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.190.135)

«A riddle, if you will: What type of artwork did Henry VIII love so much that he owned at least 2,500 examples, and Louis XIV and the Medici family value so immensely that they each established their own production workshops?»

Need a hint? They can be made of wool, silk, and sometimes even gold and silver metal-wrapped threads; their designs were prized objects in artists' workshops; Napoleon asked that his favorite portrait be re-created as one; they are among some of Raphael's most important works; and, William Morris, Peter Paul Rubens, and Francois Boucher all created designs for them. They were, without question, among the most expensive pieces of art produced during the Renaissance.

What are these extraordinarily beautiful and important art objects of which we write? Tapestries, of course!

Surprised? Certainly, since very few tapestries survive, it is difficult for us to imagine how they were once an important and ubiquitous presence in many great churches, royal residences, and noble art collections. That's not to say that tapestries were simply background noise. They were, in fact, centerpieces—dynamic components of exquisite interior spaces. Tapestries covered the walls of grand palaces and cathedrals, they ornamented royal garments and liturgical vestments, and they even depicted contemporary events and controversial ideas. They were made to be gazed upon for indefinite amounts of time as the eye slowly took in the mind-boggling amount of exquisite detail and craftsmanship necessary to create such enormous objects (large tapestries, for example, took years to weave). Made for display, like proud peacocks showing off a dazzling array of colors and precious metals, they were intended to elicit a gasp of astonishment. Tapestries were also created for private devotion, their intricate beauty meant to free the human spirit and allow it to transcend the mortal world.

Tapestries are the product of what we might think of as a modern and collaborative design process, though it began in the fourteenth century (if not earlier). The first step is a designer's sketch, which is then developed into a to-scale painting (known as the cartoon) by several other artists. Weavers then use the cartoon to craft the tapestry, sometimes making their own set of changes to the piece. By the time a tapestry is complete, scores of artists and craftsmen have influenced the appearance of the resulting design. One very important tapestry designer, Pieter Coecke van Aelst (pronounced Peter Cook-uh van Ahhl-st), who lived and worked in Antwerp and Brussels between 1502 and 1550, used this exact process to create some of the world's most astounding tapestries. He was, in a sense, a tapestry designer to the stars, creating monumental, extravagant, and breathtakingly beautiful tapestries for a who's-who of Renaissance Europe, including Henry VIII, Charles V, and Francois Ier. In celebration of his work, the Museum will exhibit twenty rarely seen, royal tapestries in the exhibition Pieter Coecke van Aelst: Tapestry and Design in Renaissance Europe, opening October 7, 2014. This exhibition will not only feature some of Coecke's astounding tapestries and their accompanying drawings and cartoons, but also several of Coecke's paintings and prints.

In anticipation of the exhibition, and to celebrate the Met's incredible collection of European tapestries woven between 1500 and 1900, today we're launching #tapestrytuesday on our social media channels (Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram). Each week we'll feature a different work—some large, some small, representing a variety of functions and possessing a range of intricate details that are ripe for observation. While we know our journey may be full of twists and turns (pun intended), we hope you'll stick with us as we take a closer look at some of the most important works of art ever created.

Sarah Mallory

Sarah Mallory is a research assistant working with Associate Curator Elizabeth Cleland in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.