You are walking through a museum, your mind lost in thought (your feet perhaps aching ever so slightly), when suddenly you look up and see a fascinating object. You immediately begin trying to identify the specimen set before you: it's a fabric . . . no, it's an embroidery . . . wait . . . it's . . . the wall label says it's a tapestry! A tapestry?

If you have ever had this experience, you're not alone. Tapestries—particularly European tapestries woven prior to the twentieth century—are relatively rare, and therefore not the types of art usually viewed on a daily basis; so, when we do finally see a tapestry, it may be challenging to identify and understand. Adding to the confusion is the fact that tapestries may seem to resemble other types of artwork such as paintings on canvas, murals, large drawings, or printed fabrics.

In the face of all this tapestry confusion, how can you determine what exactly is a tapestry? We here at #tapestrytuesday assembled a short explanation to help you to understand what, in fact, makes a tapestry a tapestry!

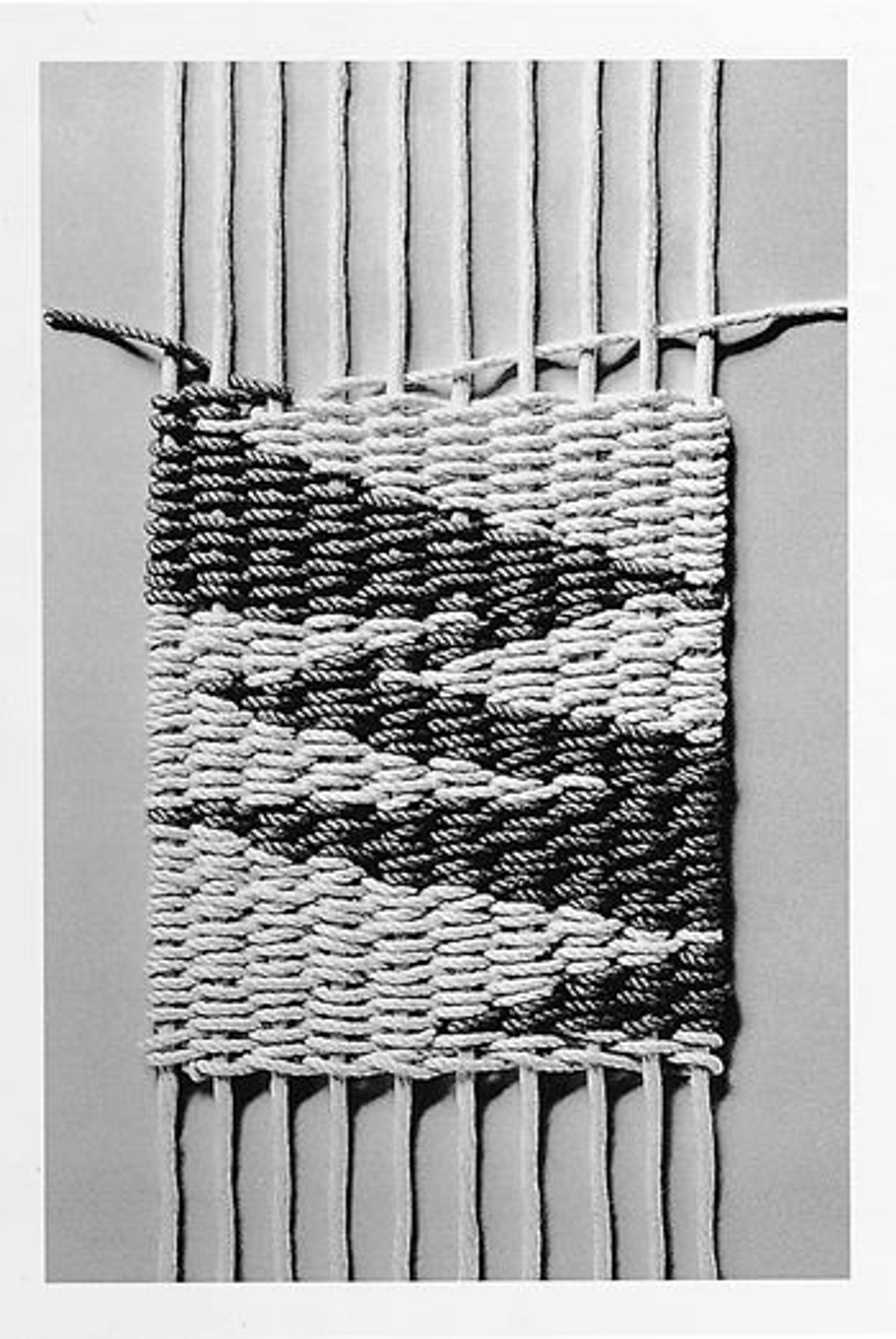

Left: Model of weft-faced tapestry weave

By definition, a tapestry is a weft-faced plain weave with discontinuous wefts that conceal all of its warps. Simply weave the warp and weft threads together, and voila—you have a tapestry! It's just that easy! Or not. If you are shaking your head in confusion while mouthing the words "weft" and "warp," we understand.

Let's break it down: At its core, tapestry-weaving is a matter of simple math. Think of a tapestry as a grid composed of threads that are fixed on a large frame (known as a loom). The vertical threads are known as warps, and the horizontal threads are known as wefts. The wefts are actually a collection of lots of separate pieces of wool or silk threads, all in different colors. A tapestry is made by repeatedly weaving the horizontal (weft) threads over and under the vertical (warp) threads, then squishing (or tamping) those horizontal threads down so they are very close together, thus completely hiding the vertical threads from view.

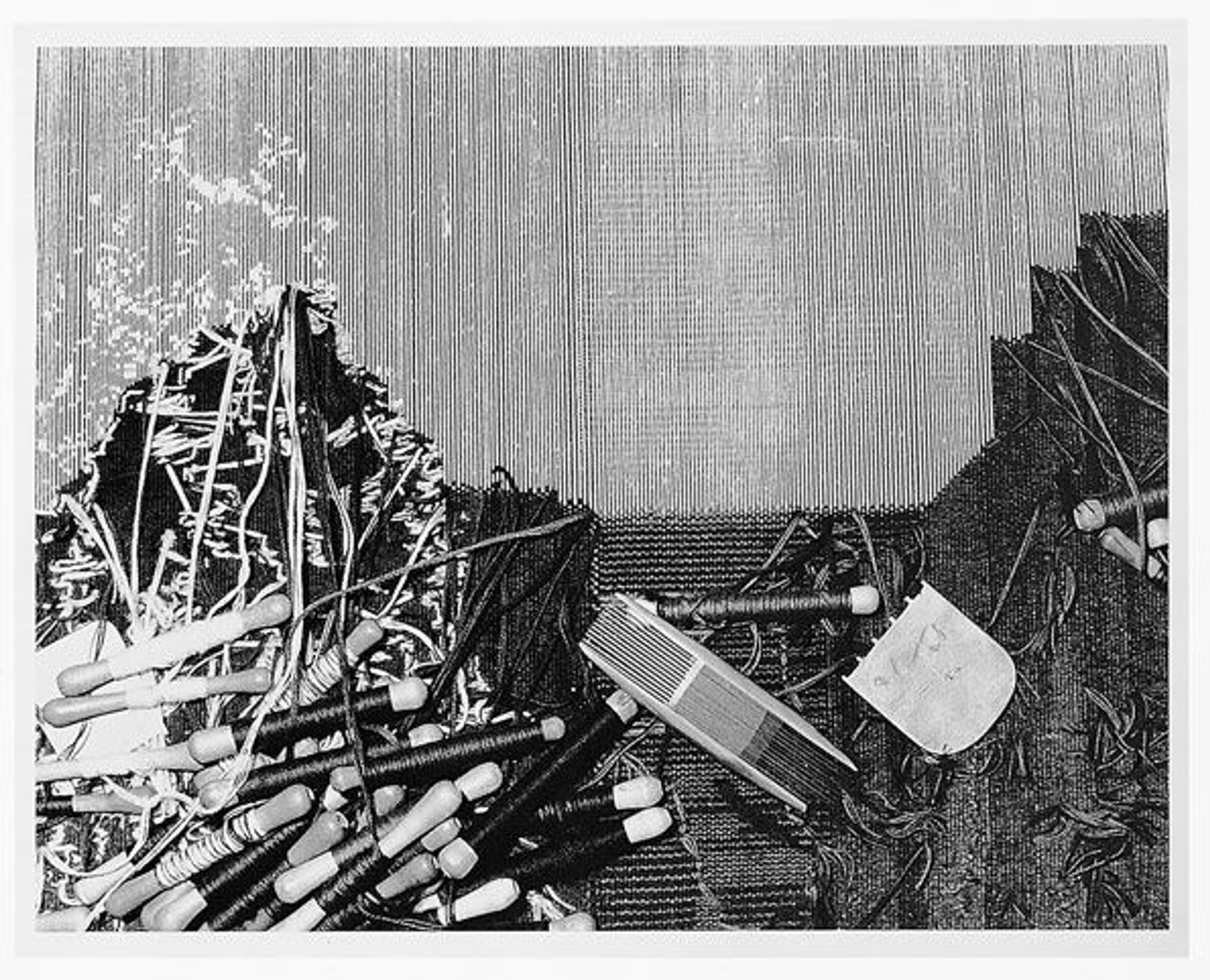

Although you cannot see them in a finished tapestry, the vertical warp threads are vital components of each piece—they are the backbone of every tapestry, and provide the support for the weft threads. Think of the warps like a blank canvas and the wefts like strokes of paint on that canvas. In other words, the weft threads are the colors which gradually build up to form a tapestry's picture. Wefts don't weave in and out across all the warps—they are only introduced where the design demands a patch of that particular color. Then they are knotted in place, their loose ends snipped off or tucked in, and another color is introduced with a different weft thread; this is why these are called "discontinuous wefts." The image below illustrates the complex array of colored weft threads partly woven onto the warp, hanging down and attached to wooden spools (or "shuttles") visible on the reverse of a tapestry during weaving.

View of the back of a tapestry being woven on a low-warp loom

Because the colored wefts entirely cover the warps, the figurative design they've built up will be visible on the front and back of the tapestry. For example, the pictures below show the front and back of a tapestry: the back, shown on top, is almost as neat at the front, shown on the bottom. Notice how the back of the tapestry is more colorful than the front; a tapestry's back, because it is rarely exposed to sunlight, is usually less faded than its front.

Anonymous Flemish weavers. Hunters in a Landscape(details; back and front), ca. 1575–95. Wool, silk; H. 70 7/8 x W. 181 7/8 in. (180 x 462 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter and Leonore Annenberg Acquisitions Endowment Fund, Rosetta Larsen Trust Gift, and Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, 2009 (2009.280)

Tapestries, though they may look like they are crafted from brushstrokes, are not painted. In fact, using paint on the surface of a tapestry was once considered a crime punishable by a large fine or worse. Though sometimes a tapestry's basic weave is altered slightly in an attempt to imitate, but not recreate, the look of other types of textiles such as silks, damasks, velvets, or embroidered fabrics.

Historically, weavers worked while facing what would be the back of the tapestry. They copied with their colored weft threads the tapestry's design. The design, referred to as the "cartoon," took the form of a painting—made on cloth or paper, the same size as the planned tapestry. This cartoon was either temporarily attached to the loom, flush against the backs of the warp threads, and visible in the gaps between the warps; or it was hung on the wall behind the weavers, who followed it by looking at its reflection in a mirror behind the warps. Because weavers copied the cartoon facing on the back of the tapestry, when the piece was finished, removed from the loom, and turned around to reveal the front, the woven image on the front of the tapestry was the mirror image of the cartoon shown. Weavers could avoid this reversal of the design by using the mirror method to copy the cartoon's design. The cartoon was not physically part of the completed tapestry, and could be reused multiple times in order to make duplicate tapestries.

Tapestries were woven by hand for centuries, but late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century technological innovations introduced the possibility of machine-woven tapestries. Today, workshops and manufactories still produce hand-woven and machine-woven tapestries. Some tapestry weavers still follow the traditional process, copying a painted cartoon; other tapestry weavers take complete creative control, even improvising their design as they weave.

Related Links

The Unicorn Tapestries: Weaving a Tapestry interactive feature

European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600 on Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1600–1800 on Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History