Journeys to Divinity: A Preview

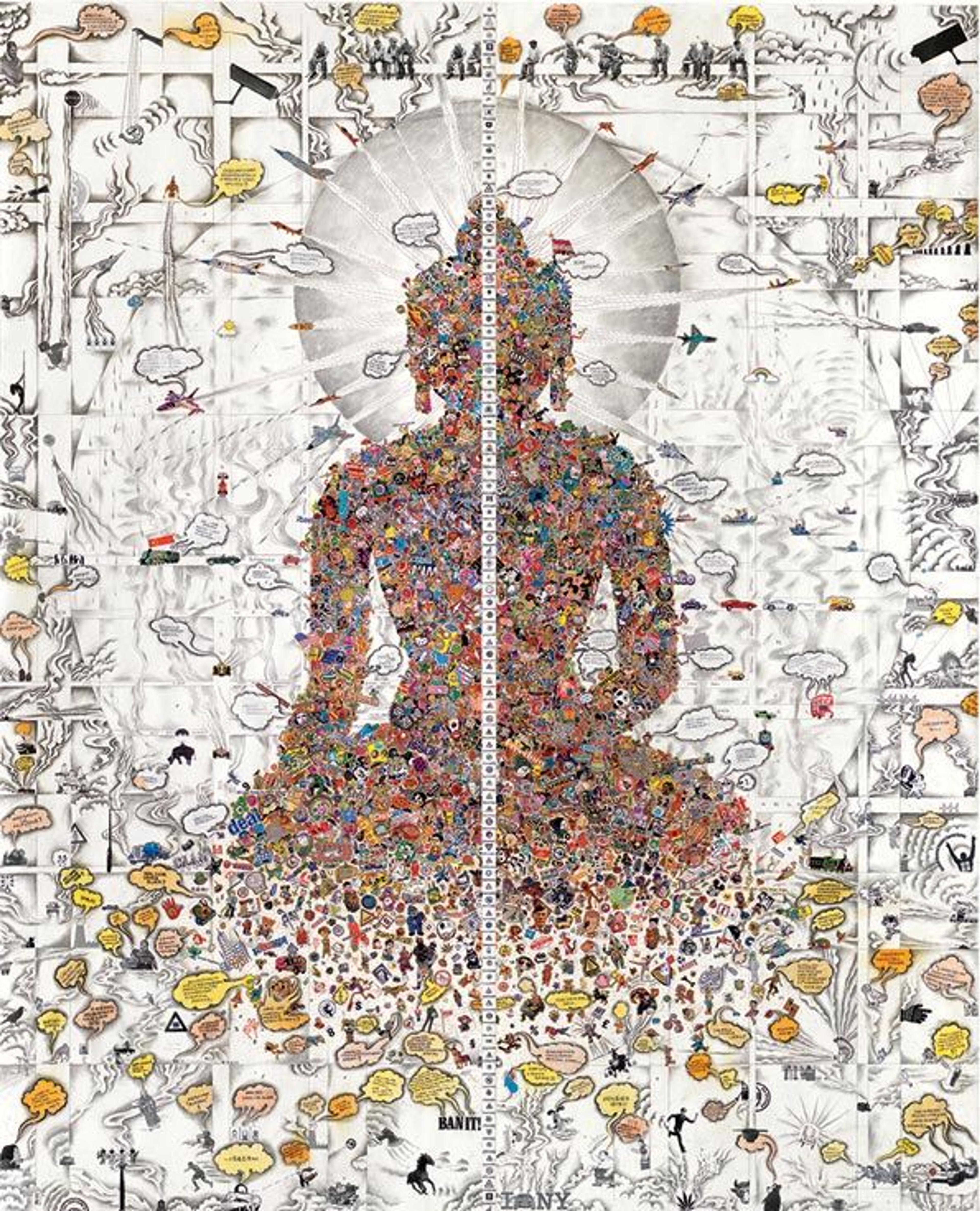

Gonkar Gyatso (born Lhasa 1961). Dissected Buddha, 2011. Collage, stickers, pencil and colored pencil, and acrylic on paper; 9 ft. 2 1/4 in. x 90 1/2 in. (280 x 229.9 cm). Promised Gift of Margaret Scott and David Teplitzky. © Gonkar Gyatso

«The upcoming Met Museum Presents talk Journeys to Divinity, along with the current exhibition Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations, touch on how imagery functions to convey complex social and religious meanings—a concept occurring today in a myriad of contexts, as the Internet penetrates deeper into our communal experience. Gonkar Gyatso considers just such media in his construction Dissected Buddha, which draws from fragments of pop culture, mass media, and advertising in a way that appeals to a broad audience and breaks down both language and geographic boundaries.»

I would argue that the imagery Tibetans encountered in the eleventh and twelfth centuries in North India had a related type of impact. Tibet was looking to India to purify their understanding of Buddhism, and the sculpture and painting they encountered were effective in expressing ideas of enlightenment, in the sense that an image of great beauty and refined form has the potential to evocatively capture sentiment and make it apparent to a new audience.

Left: Seated Buddha Reaching Enlightenment. Central Tibet, 11th–12th century. Brass with color pigments; H. 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm); W. 10 7/16 in. (26.5 cm); D. 8 5/8 in. (21.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Oscar L. Tang, Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wang and Annette de la Renta Gifts, 2012 (2012.458)

The idea that the perfected form of the Buddha was an expression of his refined actions undertaken over the course of countless lifetimes is indeed a powerful one. Or, to put it another way, perfect control of one's body is fundamentally the same as control over one's mind; thus, enlightenment can be expressed by physical perfection. Historians also look to the textual tradition to understand the Buddhist ideology of the time, and fortunately a wealth of such sources survive. Still, it is always difficult to fully understand how such texts were used and understood.

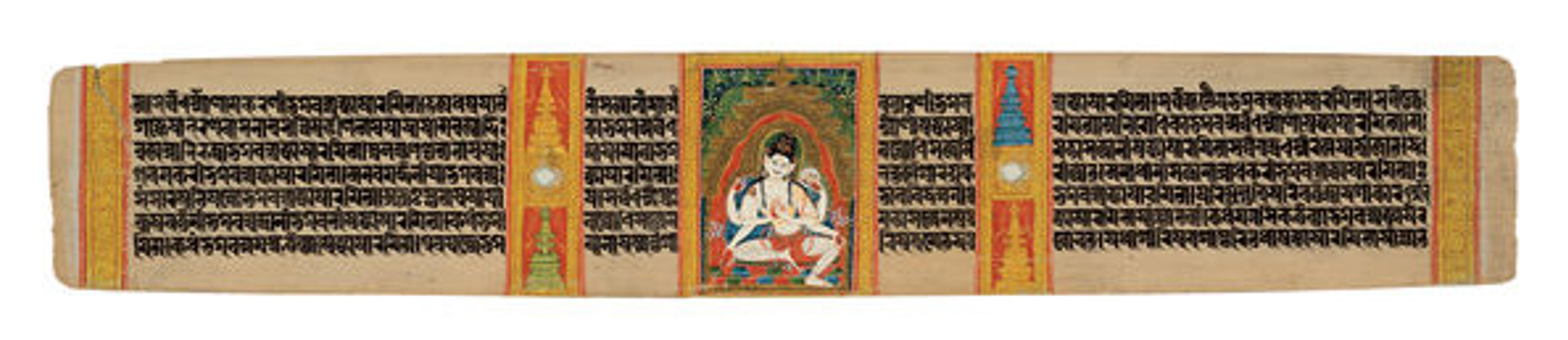

Six-Armed Avalokitesvara Expounding the Dharma: Folio from a Manuscript of the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom). India (West Bengal) or Bangladesh, early 12th century. Opaque watercolor on palm leaf; 2 3/4 x 16 1/2 in. (7 x 41.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2001 (2001.445j)

Lavishly illuminated texts were produced in North India, and many of these were brought to Tibet, where they were translated and interpreted. In fact, the Tibetan libraries of this period preserve a wealth of Buddhist sources that would otherwise not be known. The embedded imagery in the North Indian palm leaf manuscripts probably also had a profound impact on the emerging painting traditions of Tibet.

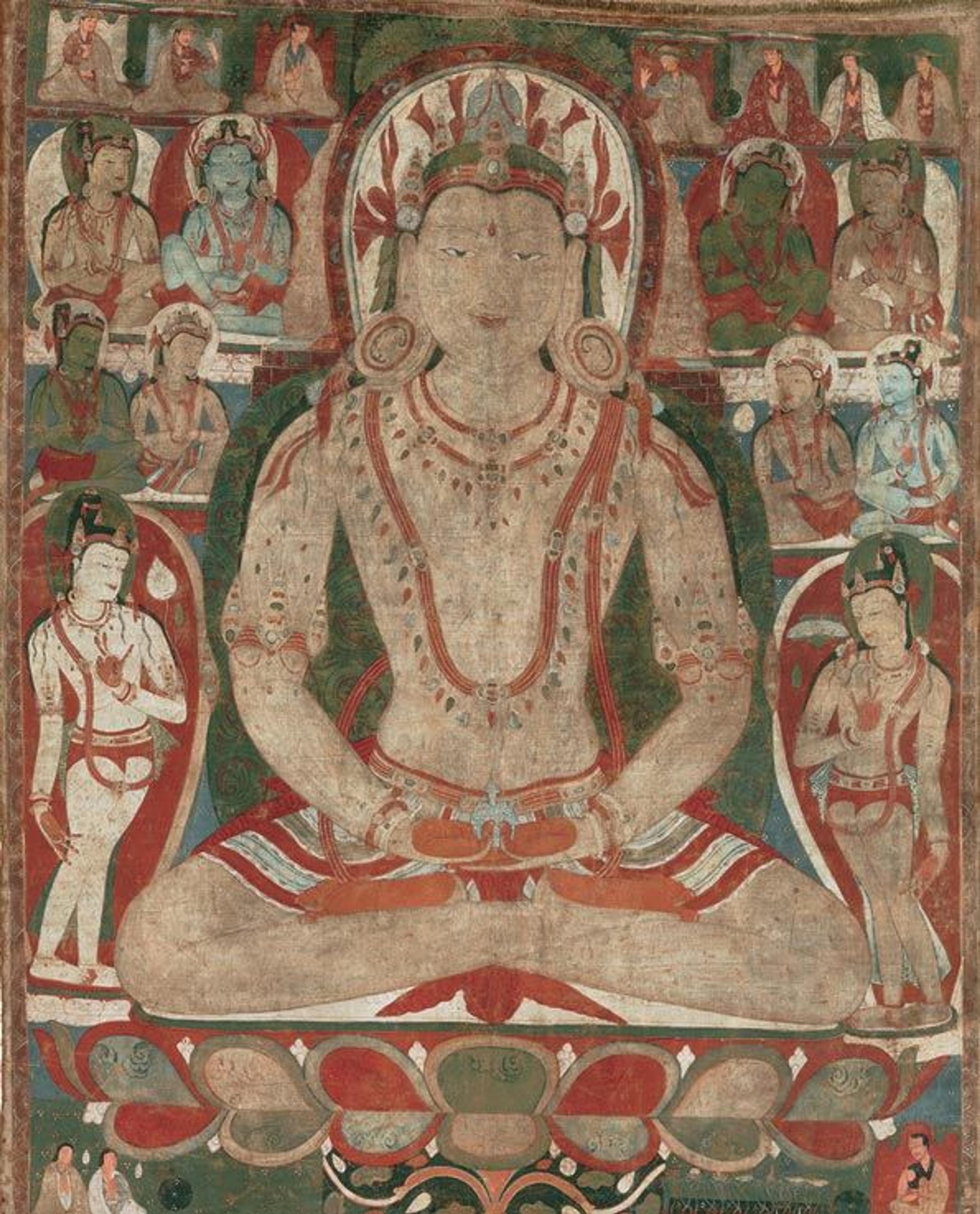

The Buddha Amitayus Attended by Bodhisattvas. Tibet, 11th or early 12th century. Mineral and organic pigments on cloth; Overall: 54 1/2 x 41 3/4 in. (138.4 x 106.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1989 (1989.284)

In this context we are fortunate that so many large and important paintings survive from the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Tibet. The power and dramatic presence of such works is undeniable, and it is easy to understand their importance for the growing Tibetan Buddhist public that encountered them.

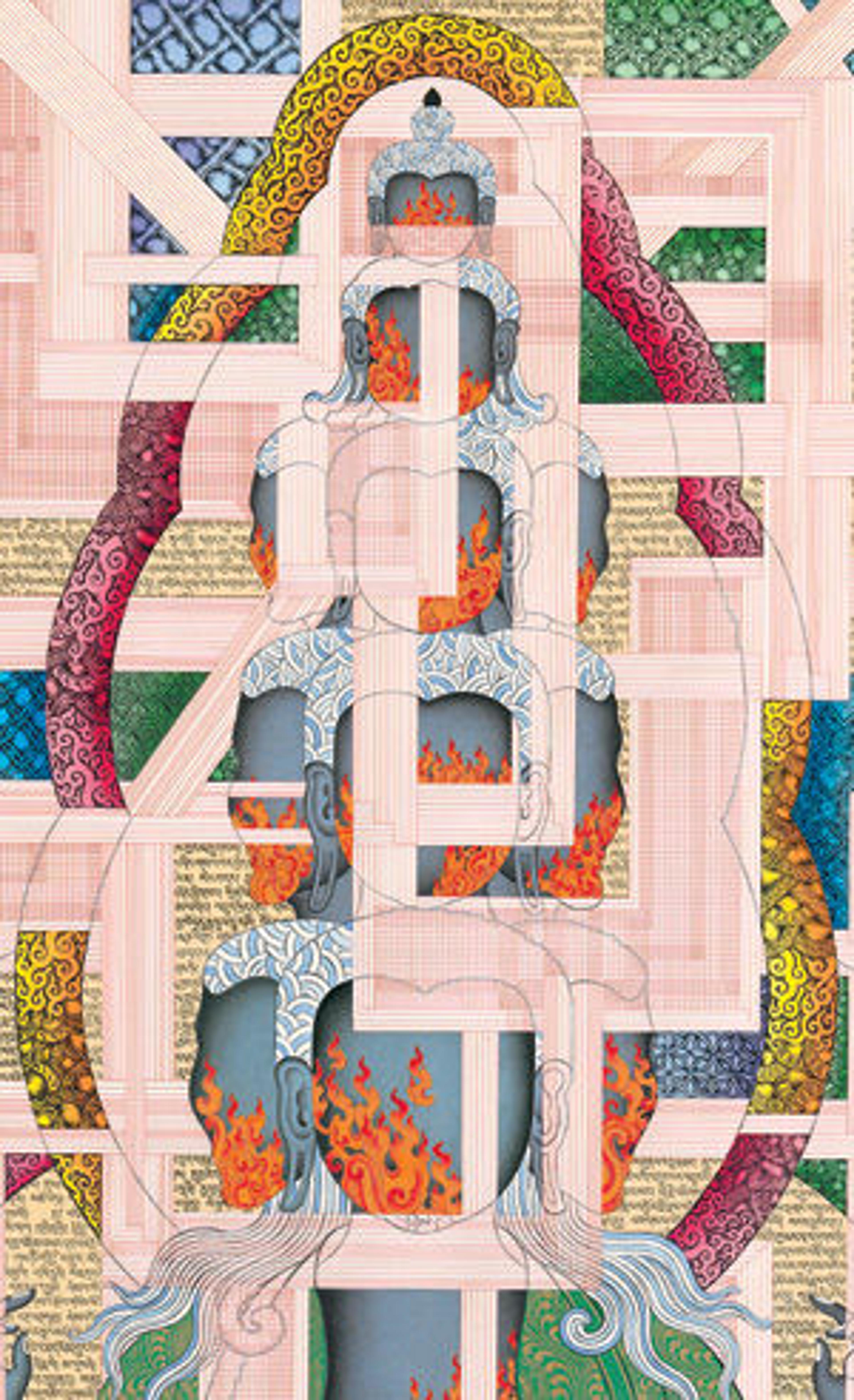

Left: Tenzing Rigdol (born Kathmandu 1982). Pin Drop Silence: Eleven-Headed Avalokitesvara (detail), 2013. Ink, pencil, acrylic, and pastel on paper; image: 91 5/8 x 49 1/8 in. (232.7 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Andrew Cohen, in honor of Tenzing Rigdol and Fabio Rossi, 2013 (2013.627)

Building on this longstanding and evocative tradition, Tenzing Rigdol's Avalokitesvara resonates with a similar kind of power. Although grounded in tradition, it is interesting to consider how he has chosen to personally express Buddhist ideas in new ways. Perhaps purposely enigmatic, we find his image lacks eyes and is fractured by a grid of red lines, which also act as the structure upon which the image is conceived. As in the twelfth century, Buddhist ideas are finding new expression as a reflection of changing times and an increasingly global audience.

To purchase tickets to Journeys to Divinity on May 20, 2014, at 11:00 a.m., or any other Met Museum Presents event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 11:00 a.m.–3:30 p.m.

Related Links

Now at the Met: Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Twenty-First Century

Kurt Behrendt

Kurt Behrendt has been at The Met since 2006. He has curated a series of exhibitions, including Bodhisattvas of Wisdom, Compassion and Power (2021), Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India (2018), Tibet and India (2014), and Buddhism along the Silk Road (2012), and has published widely on the Buddhist art of the Indian subcontinent. Ongoing field research in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Tibet provides a foundation for his exhibitions and publications. His 1997 PhD from UCLA was published as the book The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

Selected publications

Behrendt, Kurt. “Architectural Evidence for the Gandharan Tradition after the Third Century.” In Problems of Chronology in Gandharan Art: Proceeding of the First International Workshop of the Gandhara Connections Project, edited by Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart, 149-64. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2018.

———. “Buddhist Sculptures of Bihiar and Orissa from the 9th to 12th centuries: the Geographic Distribution of Iconographic types,” In Across South Asia: A Volume in Honor of Professor Robert L. Brown. edited by Rob Decaroli and Paul Lavy, New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2020.

MetPublications: Selected publications by Kurt Behrendt