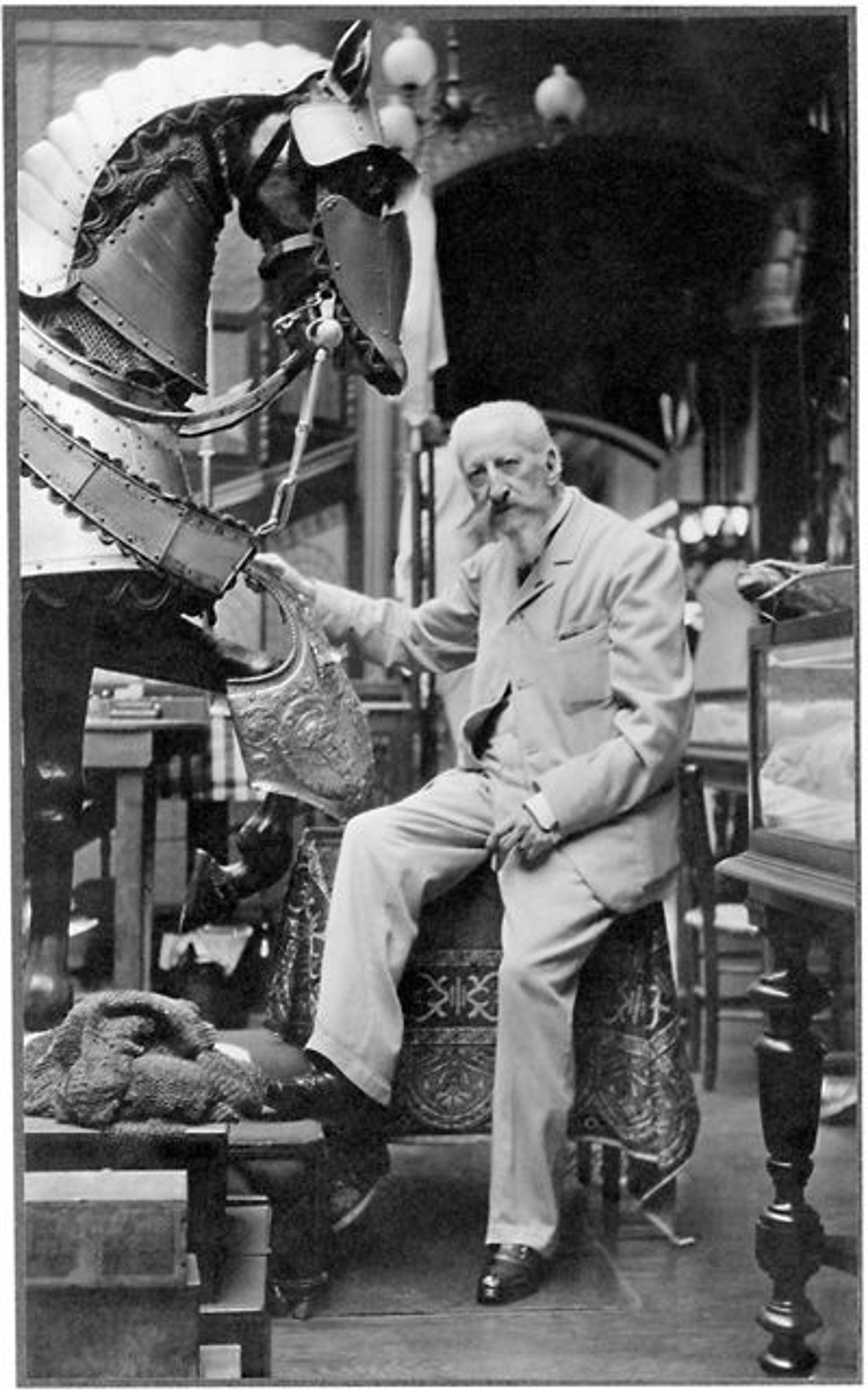

William H. Riggs in the armory at his Parisian townhouse at 13, rue Murillo, ca. 1913

«The current exhibition Bashford Dean and the Creation of the Arms and Armor Department features a number of pieces donated by William H. Riggs (1837–1924), a lifelong collector of arms and armor who assembled the finest private collection of his time before giving it to the Museum in 1913.»

The newly founded Metropolitan Museum of Art had begun courting Riggs in hopes of securing his collection as early as the 1870s but initially met with little success. By 1904, however, Bashford Dean was regularly corresponding with and visiting Riggs to discuss their shared love for arms and armor. Riggs became Dean's friend and mentor and shared with him his vast knowledge of European collectors, dealers, and restorers. In 1913, thanks in large part to Dean's involvement, Riggs donated his collection and specialized reference library to the Museum, the majority as a gift in 1913 and the remainder as a bequest in 1925. The Riggs gift, in concert with the Museum's earlier purchase of the Duc de Dino Collection in 1904, secured the position of the Department of Arms and Armor as one of the top collections in the world.

In 1915, to showcase the Riggs gift, the Museum constructed a suite of new arms and armor galleries designed by the architecture firm McKim, Mead, and White. In addition to arranging the displays and supervising their installation, Dean wrote a handbook that gave a detailed overview of the entire collection, which then totaled approximately 4,600 items (about one-third of the size it is today). The handbook featured the recent Riggs gift but also included the Dino Collection, the 1896 Ellis bequest (the first European arms and armor acquired by the Museum), and contributions by Dean and others to the Japanese holdings. The book is a model collection catalogue for the period; it includes the sources of the collection; a general history of European, Japanese, and select aspects of Asian arms and armor; discussions of objects by type, period, and culture; a gallery map; and indices. At the time of its publication, it was the most broad-ranging and comprehensive catalogue of an arms and armor collection ever written.

The gallery known as the Hall of Princes, newly installed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1915 and featuring the Riggs collection

Hundreds of pieces from the Riggs gift remain part of the permanent display of the Arms and Armor galleries today. They include many iconic symbols of the Museum's collection, such as a unique breastplate signed by the Milanese armorer Giovan Paolo Negroli (which Riggs is holding fondly in his portrait above) and a double-barreled wheellock pistol that belonged to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Left: Giovan Paolo Negroli (Italian, ca. 1513–1569). Breastplate, ca. 1540–45. Embossed and etched steel with faint traces of gilding. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.1855). Right: Peter Peck (German, 1503–1596). Double-Barreled Wheellock Pistol Made for Emperor Charles V (reigned 1519–56), ca. 1540–45. Steel, etched and gilt; wood, inlaid with engraved staghorn. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.1425)

Yet the exhibition Bashford Dean and the Creation of the Arms and Armor Department has allowed us to draw from the great depth of the Riggs collection to display some additional pieces for the first time in decades. Each is rare and important in its own distinct way.

Left: Close Helmet for a Boy, ca. 1530–40. German (Augsburg). Steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.621). Right: Hand-and-a-Half Sword, 15th century. European. Steel, leather, wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.1196)

Armor was sometimes made for the children of the nobility as a sign of the rank and status they would assume in adulthood; one example is the close helmet shown above. Although they didn't go to war, young boys wearing armor occasionally participated in tournaments fought on foot during important ceremonial events. The form and decoration of this boy's helmet relate very closely to the late work of Kolman Helmschmid (1470–1532) and early pieces by his son Desiderius (1513–1579), both leading armorers who worked for the Habsburg court in Augsburg, Germany. The etching is in the style of Daniel Hopfer (1471–1536), a prolific Augsburg printmaker and armor decorator. Although the original owner of this helmet is unknown, he must have been the son of a very important noble family.

The sword shown above is called a hand-and-a-half, or bastard, sword, referring to the length of the grip, which allows the sword to be wielded with one or two hands. We can trace the provenance of this particular sword back to the early 1800s. Before being acquired by Riggs, it was in the collection of Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick (1783–1848), founder of the modern study of arms and armor. Meyrick had purchased it from a London dealer in 1818. It was included in a watercolor sketch by the French painter Eugène Delacroix (1797–1863), which he made during a visit to Meyrick's collection in 1825. The sword was catalogued in the early nineteenth century as possibly being English, but where it was actually made remains uncertain.

Combination Dagger and Wheellock Pistol, ca. 1575–1600. German (possibly Saxony). Steel, wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.1280)

Combination weapons like this dagger-pistol were created as technical novelties and showpieces and thus were often highly decorated. The finely etched strapwork pattern on this particular piece is found on the some of the best German firearms, edged weapons, and armor of the late sixteenth century. Before one could fire this dagger-pistol, the tip of the blade had to be removed in order to reveal the muzzle of the gun barrel.

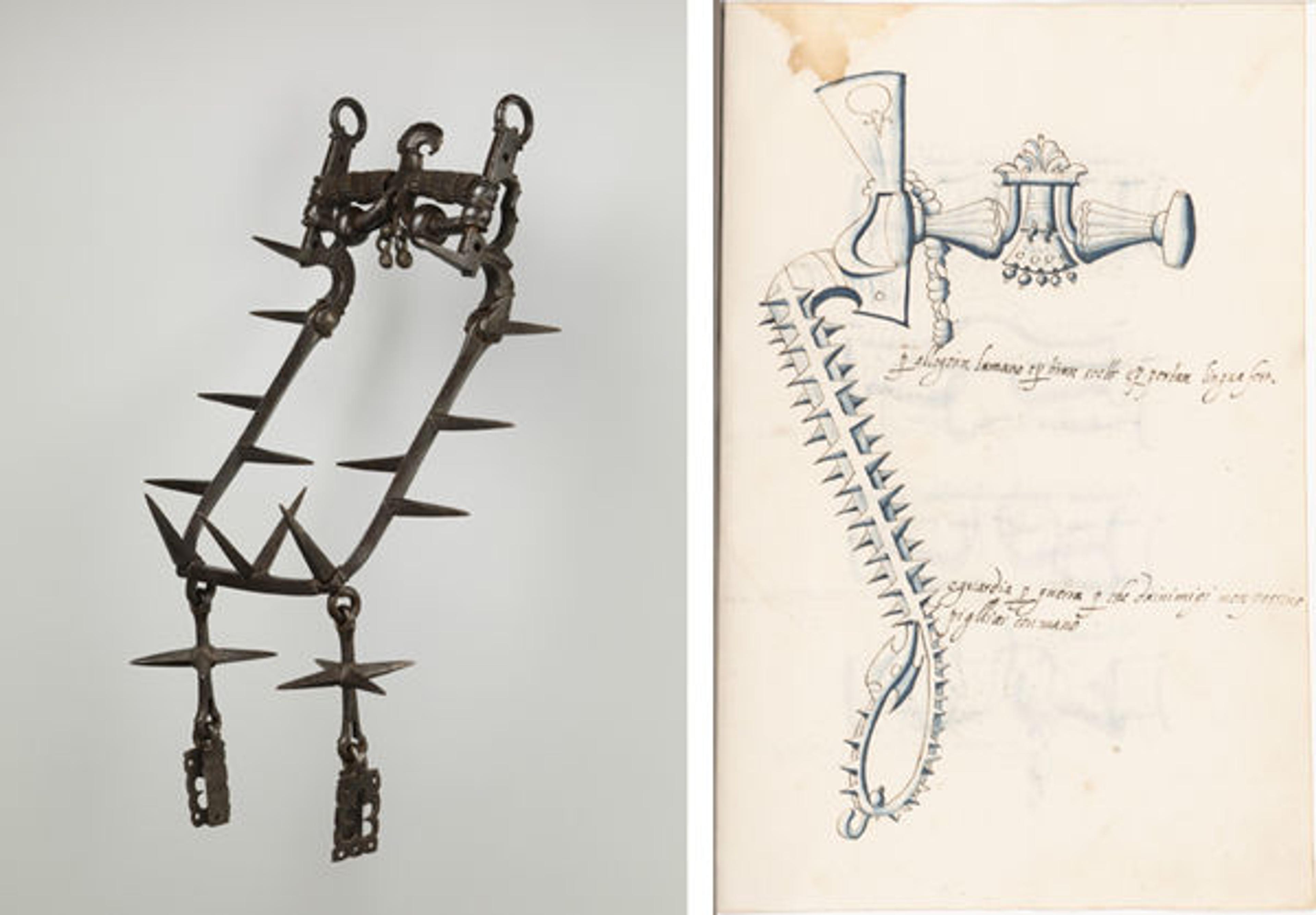

Left: Curb Bit, 16th century. Possibly French. Iron. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913 (14.25.1800). Right: Spiked Curb Bit. Illustration from an anonymous 16th-century Italian manuscript. Pen and wash on paper. Library of the Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Horses were an important part of European culture for centuries. Their breeding, care, and training were both a practical interest and favorite pastime of the nobility throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The rare type of bit shown above is described in a sixteenth-century treatise as "a defense in time of war so that the enemy cannot grab onto it with his hand." Grabbing the bit, or pulling it out of the mouth of an opponent's horse, would make it difficult or impossible for a rider to control his horse in the press of battle, potentially leading to his defeat or death.

All of these pieces represent only a small sample of those in the Riggs gift, but they give an idea of the great richness this collection has added to the Arms and Armor galleries for the past one hundred years.

Related Post

Now at the Met—"The Devoted Collector: William H. Riggs and the Department of Arms and Armor" (January 16, 2013)