Poetry, Pavilions, and Patterns: Dominga Visits The Astor Chinese Garden Court

Dominga, age 12, and David Bowles, assistant educator for School and Educator Programs, in The Astor Chinese Garden Court. Photo by Emily Sutter

«What would it be like to travel back in time 400 years and visit a Chinese garden court? Dominga, age 12, visited The Astor Chinese Garden Court to find out. While there, she wrote a poem and learned that Chinese scholars liked writing poetry in garden courts, too! Join Dominga and David Bowles, assistant educator for School and Educator Programs, on their visit.»

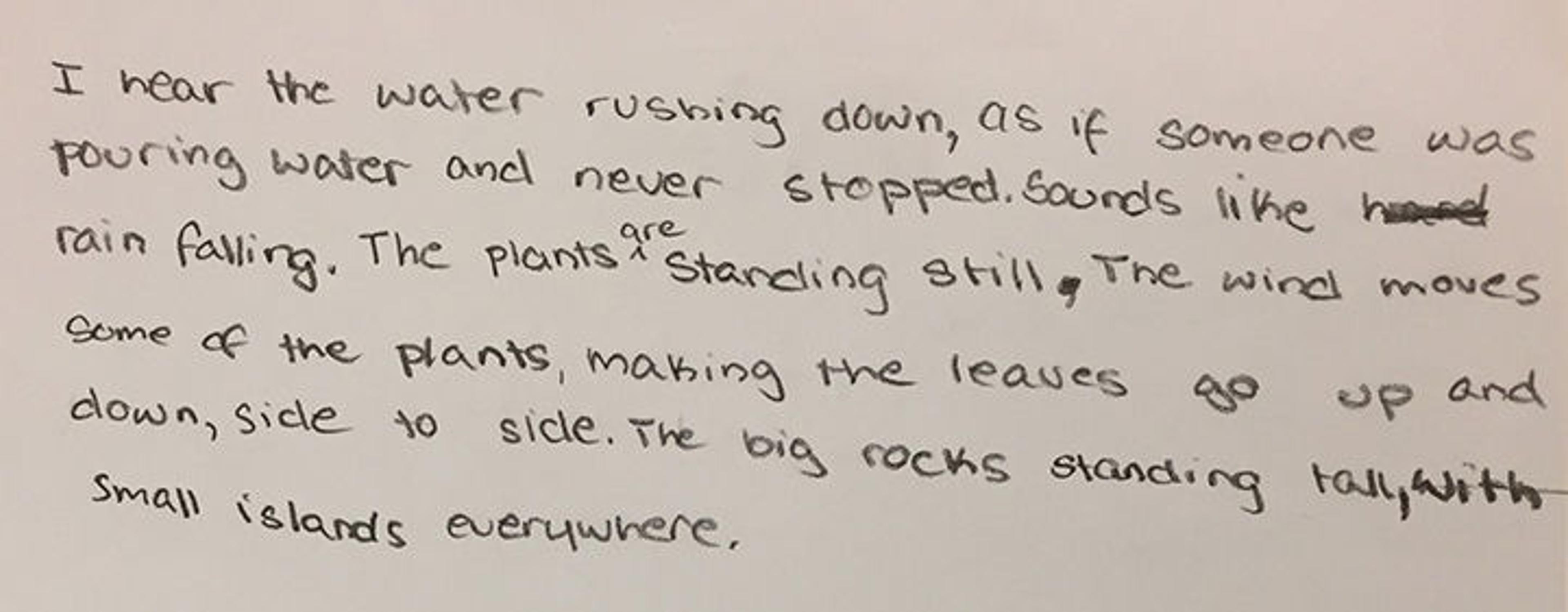

"I hear the water rushing down, as if someone was pouring water and never stopped. Sounds like rain falling. The plants are standing still. The wind moves some of the plants, making the leaves go up and down, side to side. The big rocks standing tall, small islands everywhere." Poem by Dominga

Dominga and David Bowles sit near the coy pond and write poetry inspired by the nature around them. Photo by Emily Sutter

David Bowles: I love the idea of a poetry party. I guess if you're a Ming dynasty Chinese scholar that makes perfect sense.

Dominga: Yeah, we learned the definition of dynasty. It's like a powerful family.

David Bowles: Yeah, a dynasty is the name when one family is sort of ruling an entire country.

The Astor Garden Court was built in 1980 by Chinese craftsmen, who used traditional building materials they brought from China. There are no nails holding everything together here—traditional woodworking techniques do it all! Photo by Emily Sutter

Dominga: Why was the pavilion designed with a curved roof?

David Bowles: It's actually got a cool reason. The Chinese people at the time thought evil spirits, like demons that could cause trouble for you, could only move in straight lines.

Dominga: Well, then they can't come in because it's curved.

David Bowles: If you believed in evil spirits, then you might believe that those curved lines could actually help them keep the demons away. So yeah, all of those curved lines up there are also meant to make demons sort of bounce off.

Curved roof tiles and triangular drip tiles on the pavilion. Photo by Emily Sutter

Dominga: They're kind of the same, like on the top of the roof.

David Bowles: I also think it has to do with rain, too. Don't you think? Like if the rain was falling on these buildings?

Dominga: Oh yeah, because then it won't fall straight.

David Bowles: I bet it curves the rain. Do you see these funny little triangles? They're actually meant to gather the rain as it falls. And they could . . .

Dominga: Fall into an interesting pattern.

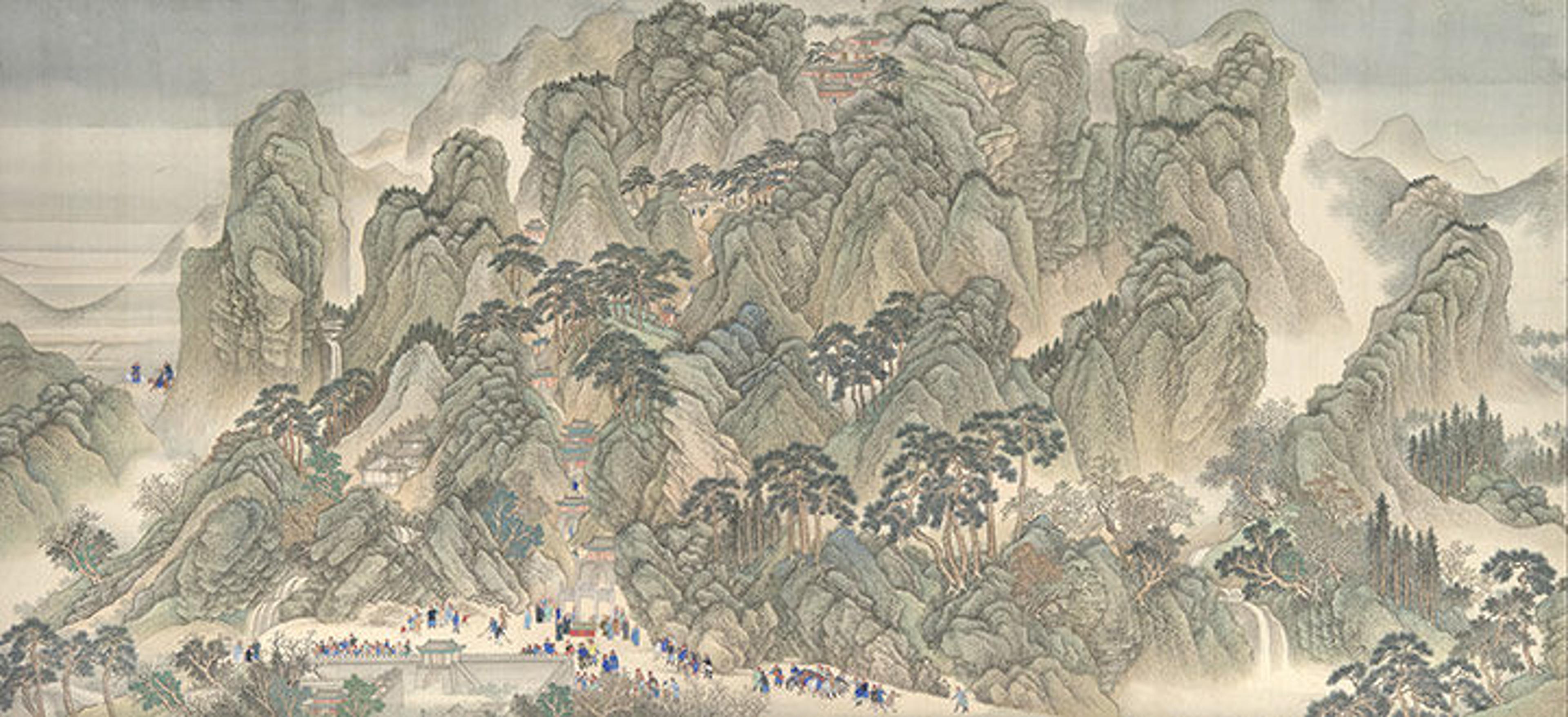

Chinese gardeners tried to recreate a landscape that would have looked similar to this scroll by using the limestone rocks to look like mountains. Wang Hui (Chinese, 1632–1717) and assistants. The Kangxi Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll Three: Ji'nan to Mount Tai, datable to 1698. Chinese, Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). Handscroll; ink and color on silk, Image: 26 3/4 in. x 45 ft. 8 3/4 in. (67.9 x 1393.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1979 (1979.5a–d)

Dominga: Are there certain types of plants in the Astor Court that make the place more refreshing and quiet?

David Bowles: Chinese garden designers want you to feel like you are looking at a landscape. So they choose plants that make you think that they might be really big trees, even though they are kind of small. They'll usually choose little bushes, but if you just switch your scale around and imagine someone three inches tall, you could imagine that being a whole forest.

Dominga: Did they put limestone rocks in the Astor Court so that when people went there, it would help them be calm and relaxed?

David Bowles: Yeah, the limestone rock is called a scholar stone. "Scholar" is a fancy way of saying somebody is a really, really knowledgeable teacher. Like, think about your teachers at school.

Dominga: Yeah, a scholar.

David Bowles: A scholar is somebody who spends all their time studying ideas and teaching about ideas and teaching other people about what they've studied.

Dominga: We've been learning about rocks for a cycle of a project, and we learned about limestone and how, like, some have large holes in them like that one.

David Bowles: Limestone to me is a really interesting rock because it is actually made of life forms.

Dominga: It is?

David Bowles: Yeah, limestone is made out of . . .

Dominga: Fossils?

David Bowles: Limestone is made out of old sea creatures that lived in the ocean millions and millions of years ago. When they died, all of their bodies fell down to the bottom of the ocean and over millions of years, layers and layers of that sediment piled on top of them.

Dominga: Just like a sedimentary rock.

David Bowles: Yeah, and eventually you get this strange rock form like this. And one of the cool things is that because it's made of many small things, it's really easy to have these cool shapes because it breaks apart really easily. So scholars in China really like these rocks because they feel that if you look at them, they could help you get cool new ideas.

Dominga and David discuss the shapes of the scholars' rocks. Photo by Emily Sutter

Dominga: I think that looks like a really big chair.

David Bowles: You know how sometimes people look up at the clouds and see different shapes? It's the same idea here. It's like with the scholars' rocks: you are supposed to look at it, think about it, imagine what it looks like, and see what kind of new ideas it gives you—especially for poetry. People in ancient China loved poetry, and gardens like this would be a place that you would come to try to write a poem about nature or life.

Dominga: In class we do creative writing. I like mostly to write about nature, because there are always different sounds that are in different places.

#MetKids would love to read your poems inspired by nature! Write a poem in the comments below or email your poem to metkids@metmuseum.org.

Emily Sutter

Emily Sutter is a producer and editor in the Digital Department.