The American Wing as Memory Palace: An Interview with Nate DiMeo

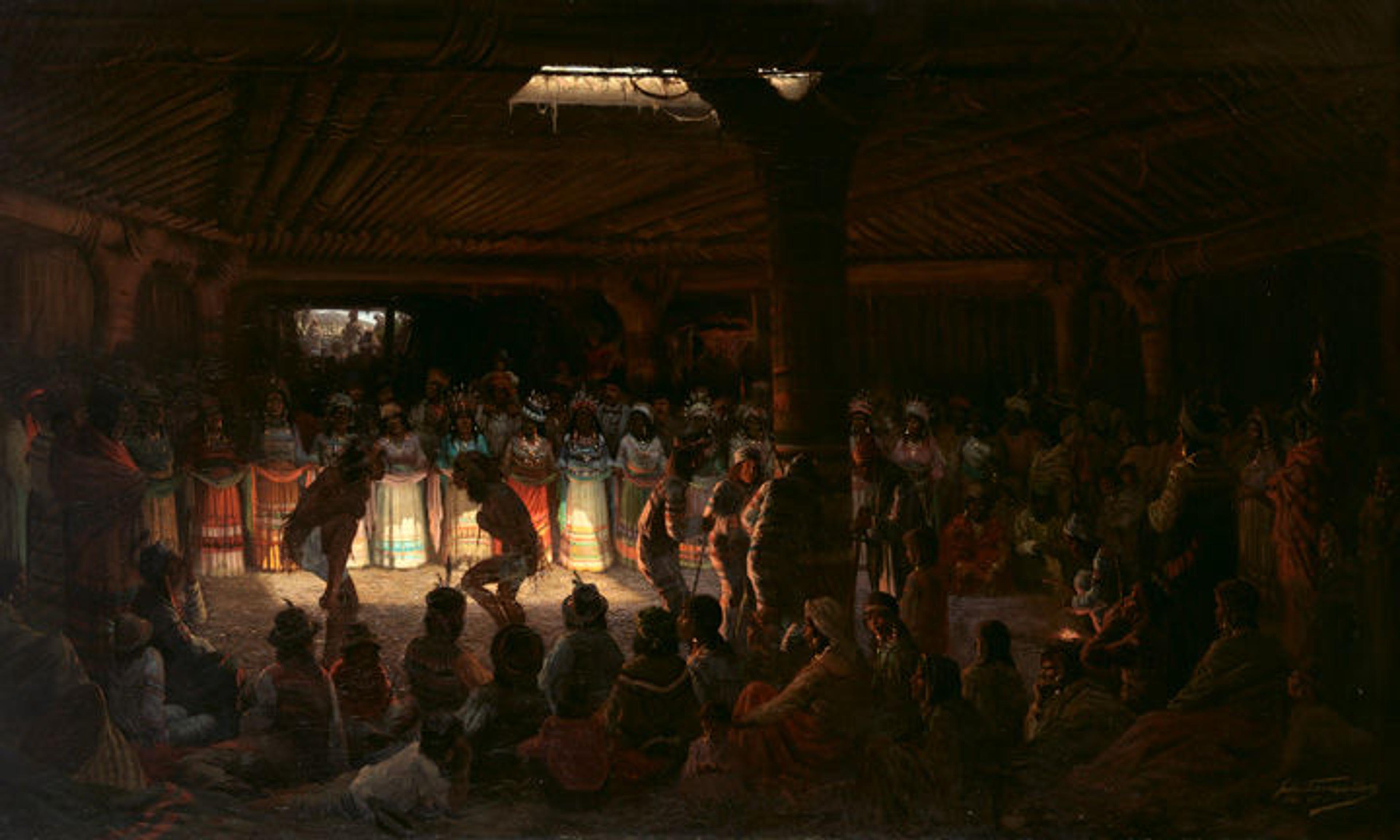

Among the artworks discussed in the first Memory Palace episode of Nate DiMeo's residency, "New Acquisition," is Jules Tavernier's Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California. Jules Tavernier (American, born France, 1844–1889). Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California, 1878. Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 1/4 in. (121.9 x 183.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2016 (2016.135)

«Throughout his 2016–17 residency, MetLiveArts Artist in Residence Nate DiMeo has released five beautiful episodes as part of his popular podcast, The Memory Palace. As everyone had hoped, DiMeo drew listeners into some of the less familiar works of art in The American Wing to reveal their exciting and moving stories. As we walk through the galleries, we often don't acknowledge that each piece of art truly does have its own fascinating history, but DiMeo knows how to dive right into each work's personal narrative.»

DiMeo will now bring his signature storytelling to The Met during a special event on May 19, The Memory Palace Live. The evening will feature DiMeo spinning his tales to a live audience in The Charles Engelhard Court, accompanied by guitarist and composer Brandon Ross. Ahead of this event, I recently had the chance to speak with DiMeo to discuss his creative process and how each episode was inspired and developed.

Meryl Cates: All but one of the episodes you created throughout your residency were inspired by The American Wing. Why this area of the Museum, of all The Met's galleries? What inspires you about this collection in particular?

Nate DiMeo: I have an abiding fascination with what makes the past "Historical" and what cultural forces come into play to capitalize that "H": the events, people, and moments in the past that resonate, enduringly or otherwise. Now, I'm a sucker for any collection of American art. I love its history, and I love much of the work itself. But what fascinates me about The Met's American Wing in particular is how this institution—through what it has chosen to purchase and display and how—plays an active role in capitalizing that "H." Washington Crossing the Delaware is a big deal, in part, because it's a big deal here at The Met. The Museum has been the ideal place to explore these ideas.

DiMeo's second Memory Palace episode created during his residency, "One Bottle, Any Bottle," takes a close look at this 19th-century pocket bottle. Left: Pocket bottle, 1815–40. American, possibly made in Pennsylvania, United States; probably made in Ohio, United States. Blown-molded glass, H. 5 in. (12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Henry G. Schiff, 1980 (1980.502.62)

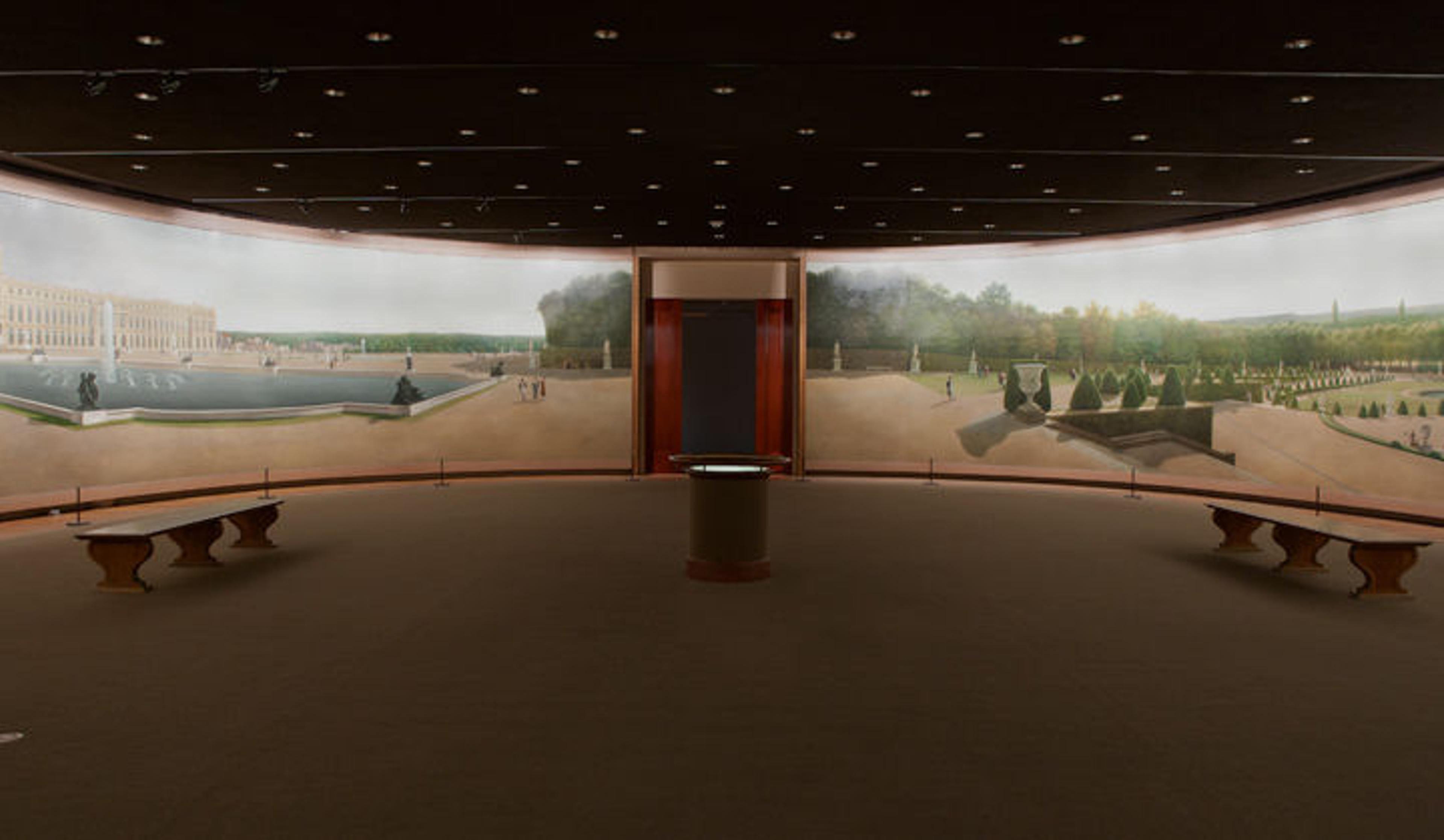

Meryl Cates: You have explored a Jules Tavernier painting, glass bottles, and the Vanderlyn panorama, just to name a few. How do you select your topic for each episode? Are you drawn to the artwork right away?

Nate DiMeo: Despite all the necessarily misty, ephemeral, epiphanic, alchemical whatnot that goes into creating episodes of The Memory Palace, my approach to finding subjects is the same: I wait to be moved.

I consume a lot of culture. I read a lot, and I watch a lot. Like anyone, I've got a million tabs open on my browser. We're all inundated with information and stories and noise, but every now and then one of these stories, one of these factoids, one of these links or videos jumps out of that stream of information and moves you. It changes your day. It hangs with you. It becomes the thing you can't wait to tell someone when they come home. It becomes the thing you remember weeks later out of the blue. Sometimes you're not even sure why, and I've learned to honor that. So, in practical terms, when something with a historical bent emerges from the noise to move me, I take a note of it and look to develop it as a possible story.

I've taken this same approach to my work at The Met. Swap out the overwhelming amount of information from our current day for the overwhelming experience of a day at The Met and you've got the idea. So I wander the halls and wait to be moved—waiting for a particular artwork or idea to grab me, and taking notes along the way. I'll then start to dig deeper, through research and asking questions of curators, to see if there's a story there.

For the third episode of his residency, "Full Circle," DiMeo focuses on John Vanderlyn's Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles. John Vanderlyn (American, 1775–1852). Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles, 1818–19. Oil on canvas, 12 x 165 ft. (3.6 x 49.5 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Senate House Association, Kingston, N.Y., 1952 (52.184)

Meryl Cates: Are some of the more subtle details that you discover and elaborate upon things you notice yourself and pop out to you, or do they reveal themselves after conversations with curators?

Nate DiMeo: Both. Making these pieces is ultimately about finding things that connect with me personally and then finding ways to create pieces that will connect with the listener. I am your guide, in a way, trying to draw out the wonder from a subject, which is not all that different from a curator's job. Over and over I'm struck by the fact that the real gift of being artist in residence at The Met is being able to turn to a curator and say, "This painting/sculpture/needlepoint is fascinating, tell me about it," and having them say, "Do you want to know what's really fascinating? Look here . . ."

Meryl Cates: In your research, do you ever discover any really fascinating details or backstories that don't make the final cut of the episode, either because it would send you too far down the rabbit hole or because you need to maintain a certain length to the episode? If so, what was one of the hardest cuts you've had to make for your Met episodes?

Nate DiMeo: I have an almost fetishistic relationship with concision. So every cut, I'd like to think, is earned—and weirdly welcome. I don't look at what's left out with any sort of longing, but there definitely have been a number of stories I just haven't been able to make work. That usually means I have trouble turning "Isn't that beautiful!" or "What a fascinating anecdote!" into a story, something that resonates more deeply. Often, that's just my failing.

Sometimes I realize there's just not much there once I start digging. For instance, I was sure I'd do a story about Randolph Rogers's sculpture Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii—so sure, in fact, that the folks at The Met used its image in materials promoting my residency! But having read and read about Rogers and about the sculpture's historical moment, I was never able to get deeper with it beyond the initial rush of fascination.

"A Portrait," the fourth Memory Palace episode DiMeo created during his residency, gives insight into Prince Demah Barnes's Portrait of William Duguid. Right: Prince Demah Barnes. Portrait of William Duguid, 1773. Made in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Oil on canvas, canvas: 20 3/4 x 15 3/4 x 1 1/8 in. (52.7 x 40 x 2.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 2010 (2010.105)

Meryl Cates: What's in store for The Memory Palace Live? Have you ever done a live podcast episode or listening experience?

Nate DiMeo: I do live performances fairly frequently. I've toured a bit with a live show in the United States and in Toronto, Canada. Earlier this year I even read stories while kind of DJ'ing music clips in the rain at a rock festival in Tasmania. This is an entirely different proposition though. There's a challenge here in performing pieces that are tied to specific artworks and rooms within the Museum while not actually standing with the art. I'm working on incorporating some visuals into the performance space that will provide context as necessary, but the feedback that I've gotten on the pieces from people who've never been to The Met makes me encouraged that the writing itself will be sufficiently transporting.

The secret weapon to this event will be the space itself: there's a magic to The Charles Engelhard Court. There are a number of works right there in the room—including Nydia—that I've explored as possible subjects. While they might not have taken hold enough to make a full piece, I'm going to use this live performance as a way to share some of what I love about those artworks. There will be several moments within the show that one might think of as mini Memory Palace episodes in which I hope I'll be able to draw out some of the wonder from the room and from The Met as an institution.

To purchase tickets to The Memory Palace Live or any MetLiveArts event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 11 am–3:30 pm.

Meryl Cates

Meryl Cates is a senior publicist in the Communications Department.