«At its inception, George Grey Barnard's Cloisters museum, located at 700 Fort Washington Avenue in New York, was conceived to provide American art students with access to examples of medieval craftsmanship. A stone carver and collector of medieval art, Barnard promoted the educational value of looking at original stone monuments from Europe. This "Gothic dream," as he called it, now constitutes the core collection of The Met Cloisters.»

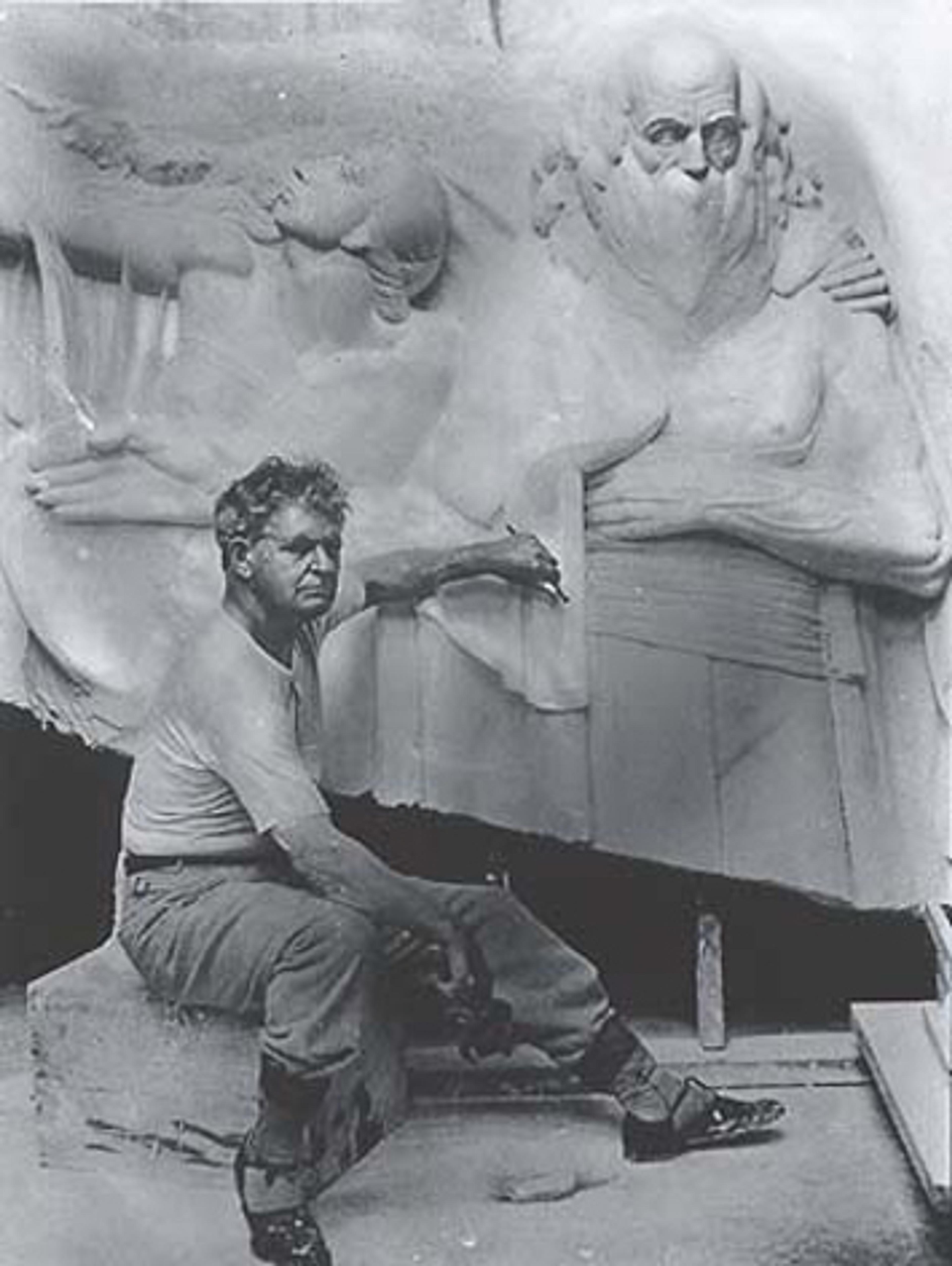

Left: George Grey Barnard (1863–1938) at work in his studio. Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum J0001282

Today, The Met Cloisters incorporates architectural elements within its structure, including arcades from a Benedictine priory in Froville, in northeastern France.

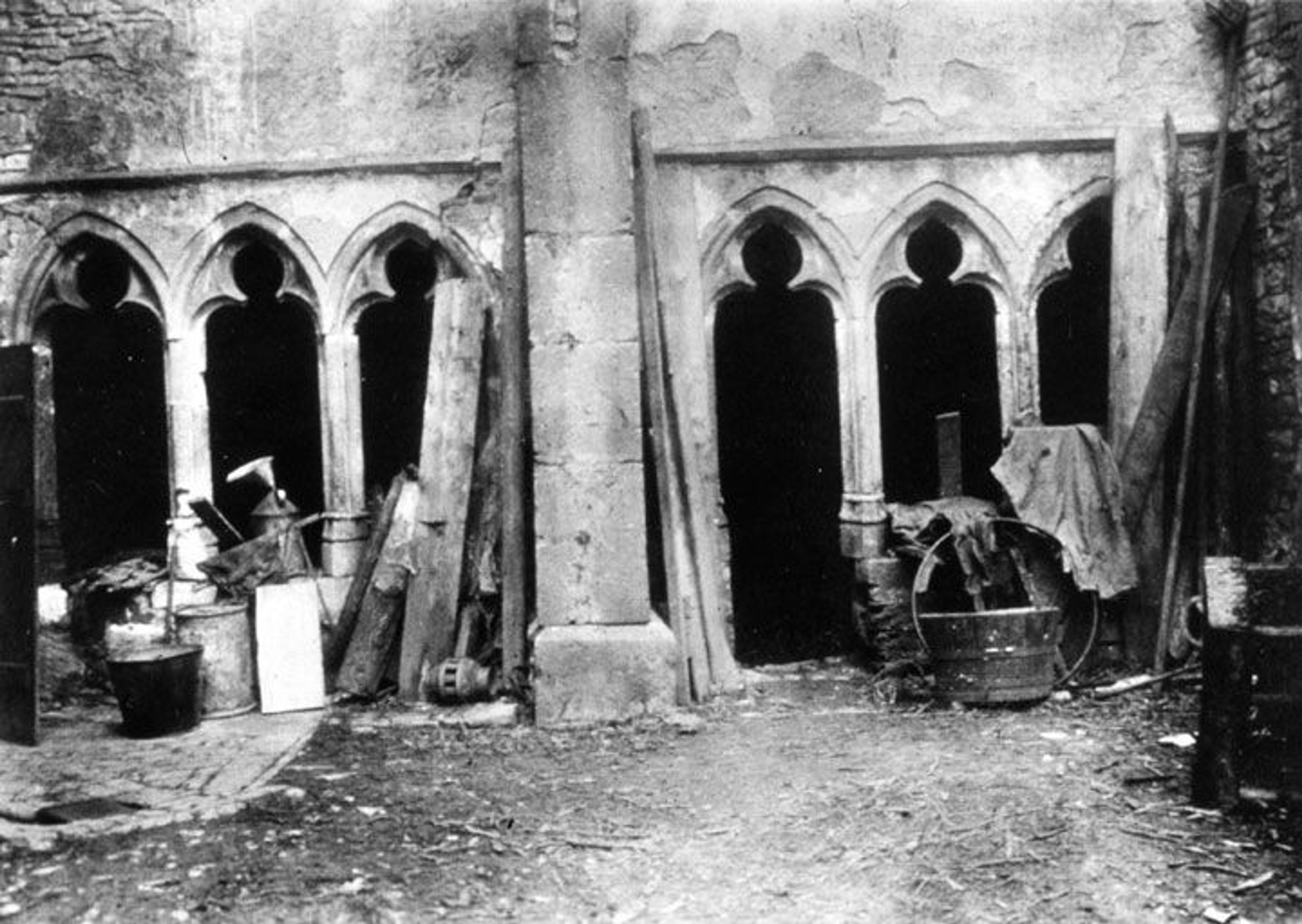

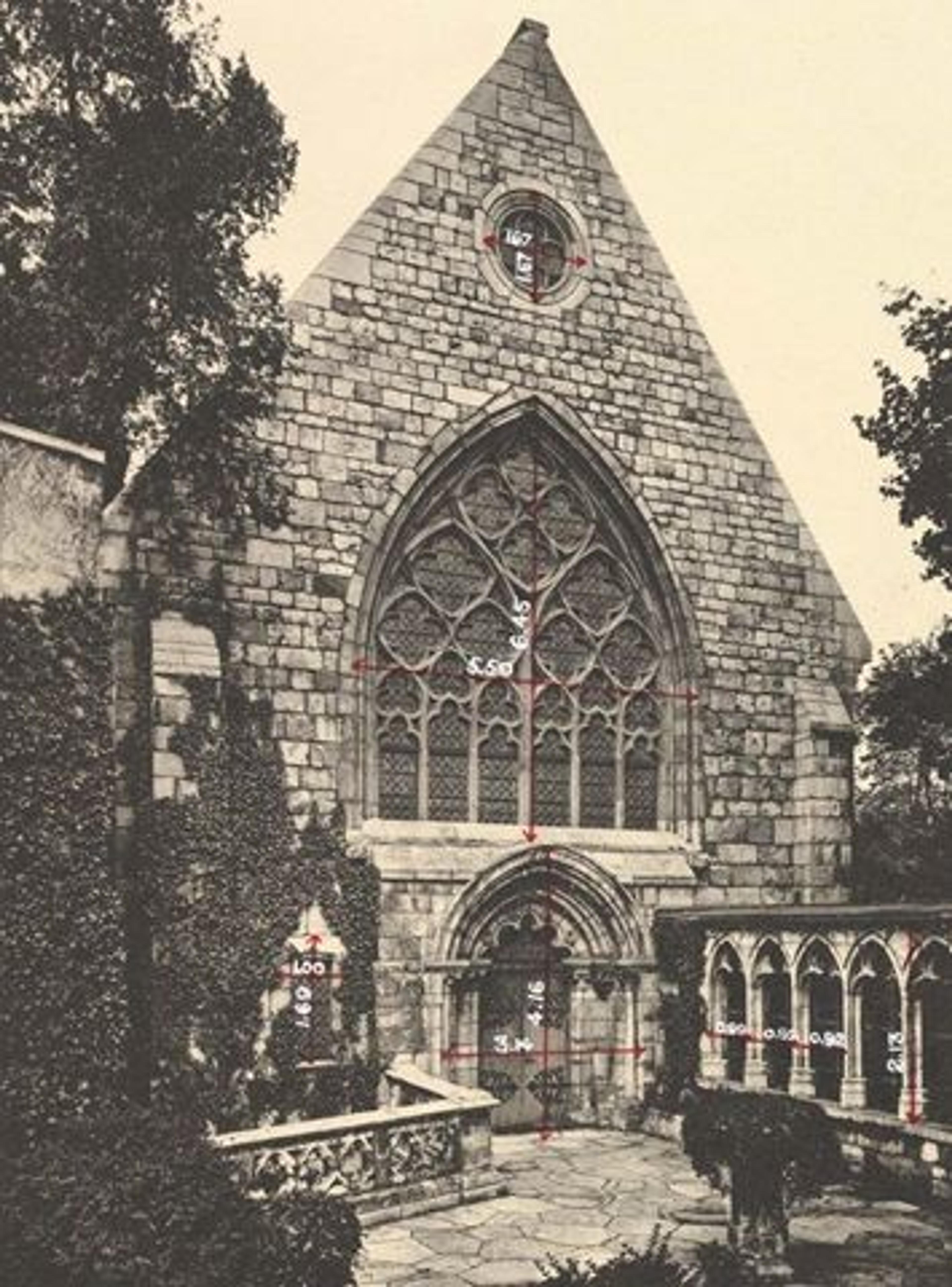

View of the Froville stone arcade at The Met Cloisters

Used as an agricultural building after the French Revolution, the 15th-century stone arcade was moved to Paris in the early 1920s to decorate the private home of the art collector and banker George Blumenthal.

Arcade from the cloister at Froville, France, prior to 1920

Donated to The Met in 1935, the three triple ogive bays have become a hallmark of The Met Cloisters' side entrance. To a select audience, this archway holds immense significance, representing materials from a region close to the heart of the collection, and artisanship from an illustrious past.

Right: George Blumenthal Salle de Musique in Paris, early 1920s. The arcades from Froville can be seen at bottom right. Photo courtesy of The Cloisters Library and Archives

The recent visit of a group of five laureate stone carvers and their professor from the Lyceum Claudel in Remiremont, France—a technical school near Froville—was one such occasion where The Met becomes a center of cultural exchange and friendship. As students in a five-year professional training program in stone carving, these carvers represent France's future generation of craftsmen capable of restoring certain elements of cathedrals or historical monuments. Besides experiencing the pride of seeing their patrimony displayed in a museum of international reputation, coming to The Met Cloisters was an occasion for them to share their expertise in stone carving using medieval techniques.

Although the students were hoping to provide a live demonstration of their skills to audiences at The Met Cloisters, stone carving is a particularly dusty venture. Within a museum environment, it presents heavy logistic issues, including risks from flying stone chips and the infiltration of dust into the collection. Dust, especially of stone origin, is abrasive on a microscopic scale, with tiny sharp mineral particles such as quartz. It is also hygroscopic, and if deposited on art will bring increased moisture to surfaces and possibly catalyze chemical reactions.

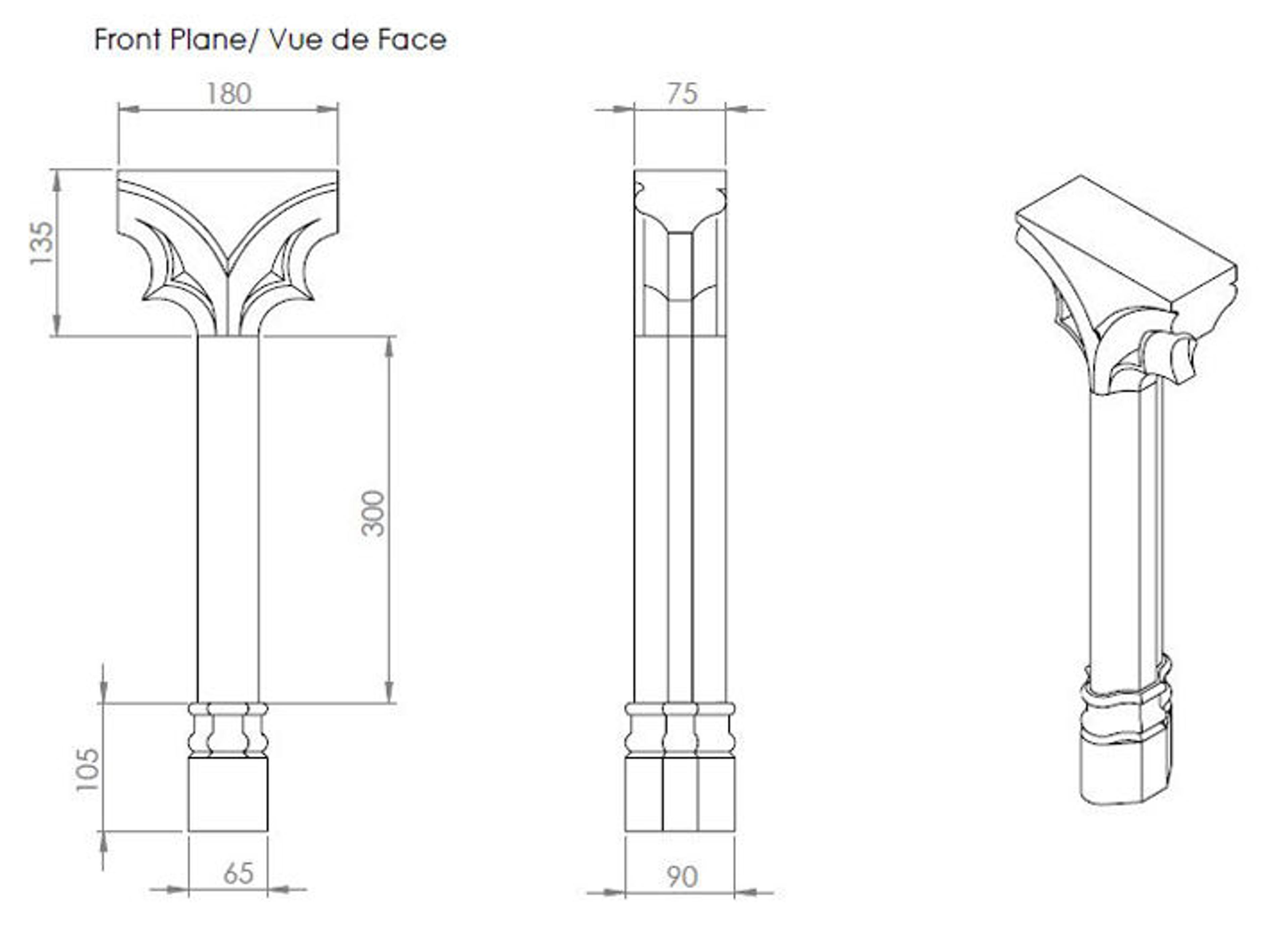

In order to bring to reality the French carvers' aspirations to create a miniature reproduction of the Froville stone arcade, the Museum collaborated with a sculpture center in New York, The Compleat Sculptor, to provide an appropriate space to carve stone and adequate material. Masters of their trade, the group first drew careful plans with measurements of the various sections.

One of the plans created by the French students

Starting from rectangular blocks of Indiana limestone, they roughed out the arcade's main shapes previously drawn onto the stone, chiseled more delicate designs of molding, and finalized the finish with rasps and sand paper (sand and cloth, or even shark skin, would have been used in the Middle Ages).

The students at work. Photo by Nicolas Lemé, stone carving professor at the Lyceum Claudel

Video by Nicolas Lemé

The completed exercise was exhibited for an afternoon in the Fuentidueña Chapel, where the group gathered for an informal discussion with the public.

Left: The students display their work and speak with visitors in the Fuentidueña Chapel. Photo by the author

The visit of these French students could not have been more appropriate for The Met Cloisters collection. Beyond providing sheer aesthetic pleasure and an encyclopedic display of works of art, the Museum serves an important role—as a powerful link to art and to sculptural traditions from foreign lands. Ultimately the project fulfilled Barnard's goals of bringing medieval art to an American audience, and using these works as a teaching tool for current artists.