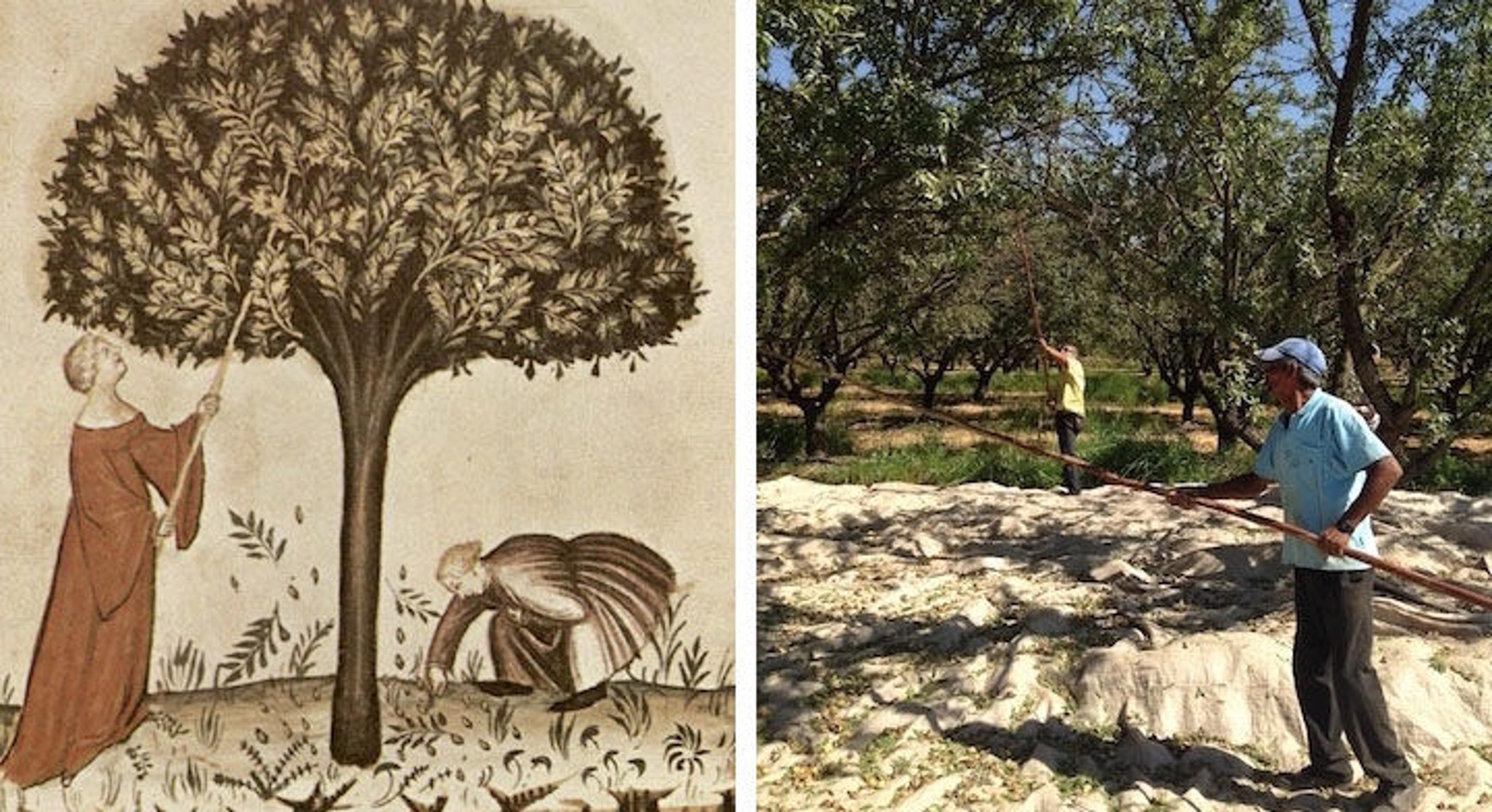

Mis suegros, Jorge and Anita Garcia-Huidobro, on their lovely almond orchard in Huelquen, Chile. They have been growing almonds and much more since 1963. Photo by Sebastian Garcia-Huidobro

«I've recently returned from the mystical land of Chile, where my in-laws manage an almond orchard that was in the midst of its annual harvest. Their lovely land also cultivates, among other things, peaches, apricots, and plums (which are all relatives of the almond), along with quinces, apples, grapefruits, oranges, lemons, avocados, a mixture of delicious vegetables, and, my personal favorite, raspberries.»

Their main production, however, is the highly prized sweet almond (Prunus dulcis), which thrives in the central region of Chile, a dry Mediterranean climate with a maddeningly intense sun. The valued sweet almond is not only productive, but also ornamental, adorned with elegant pinkish-white flowers. It's nothing short of a dream to see their orchard in bloom.

Left: Illustration of an almond from The Grete Herball, printed in 1526 by Peter Treveris. Currently on view in the exhibition Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures, on view at The Met Cloisters through May 21

It takes approximately seven months for the fruit to mature after it has been pollinated by the lovely honeybees. An almond is technically not a true nut, but a drupe, or stone fruit. A drupe, which comes from the Latin druppa, meaning overripe olive, is composed of a fleshy or pulpy outer layer with a hard shell inside that holds a seed. Once the outer hull splits open, it's time to harvest the valued "nut" inside.

A relatively small tree, Prunus dulcis will reach approximately 15 feet tall and grow the same in width. Although native to Central-Western Asia, these trees can grow wherever favorable conditions allow. In fact, the earliest evidence of wild almonds being gathered and eaten were seen in caves in southern Greece that date to the Stone Age, nearly 10,000 years ago. California now ranks highest on the list of almond producers, accounting for approximately 70 percent of the world's almonds.

The sweet almond was domesticated from the wild almond, or bitter almond, which was known to be poisonous. Seeds were saved from the almond trees that tasted "sweet" and lacked the dangerous prussic acid. In medieval Europe, sweet almonds were used in stews and made into almond milk and butter, which were important substitutes during religious occasions when animal products were not consumed. Oil extracted from the bitter almond also serves as a common ingredient in baking sweets such as marzipan.

Left: "Almonds, Amigdale dulces," from The Four Seasons, The House of Cerruti, which states: "In the month of August, when the outer shell begins to crack, the almonds are knocked down from the trees. The large, sweet ones are the best and they have singular qualities; they overcome anxiety, remove freckles, and eaten before drinking, they prevent drunkenness . . ." Right: Things haven’t changed all that much: these two hard-working men have been harvesting almonds for decades. Photo by Sebastian Garcia-Huidobro

At the orchard, workers still harvest in the traditional manner: they shake the branches! Blankets are laid beneath the almond trees, which are then shaken or beaten with long sticks, and the fruit is gathered on the cloth and then placed in a cart. The blanket is pulled from tree to tree and workers harvest row by row. The almonds are then carted to an open field where they are spread thinly on the ground to dry in the sun for a few days. The crew of five men work for nearly two months to complete the harvest of 4,000 trees, which yields them approximately 15,000 kilos of almonds!

After watching the men tirelessly harvest these fine delicacies, I'll never moan over the high cost of an almond again. Perhaps their beauty and bounty explain the Roman tradition of tossing almonds at newlyweds for fertility, good health, and fortune.

Almonds drying in the sun after harvest. In the company of my daughter, Fiona Iris, the harvesters and the resident dogs are hard at work. Photo by Sebastian Garcia-Huidobro

Resource

Roberts, Jonathan. The Origins of Fruits and Vegetables. New York: Universe Publishing, 2001.

Related Article

In Season: "Acres of Acorns" (November 5, 2015)