Here I Sette My Thynge to Sprynge

Reticulated iris (Iris reticulata "Harmony"), left, and Narcissus, right, in the arcades of Cuxa Cloister. Photographs by Carly Still

«Although the vernal equinox is mere days away, this week is our first taste of spring. For most people, the start of spring is a celebrated event that signals longer days and warmer temperatures. In medieval Europe, spring was considered a highly auspicious time; in many parts of Western Europe, it marked the beginning of a new year and included one of the most important occasions, the Feast of the Annunciation (see "Lady Day" [March 25, 2011] on The Medieval Garden Enclosed).»

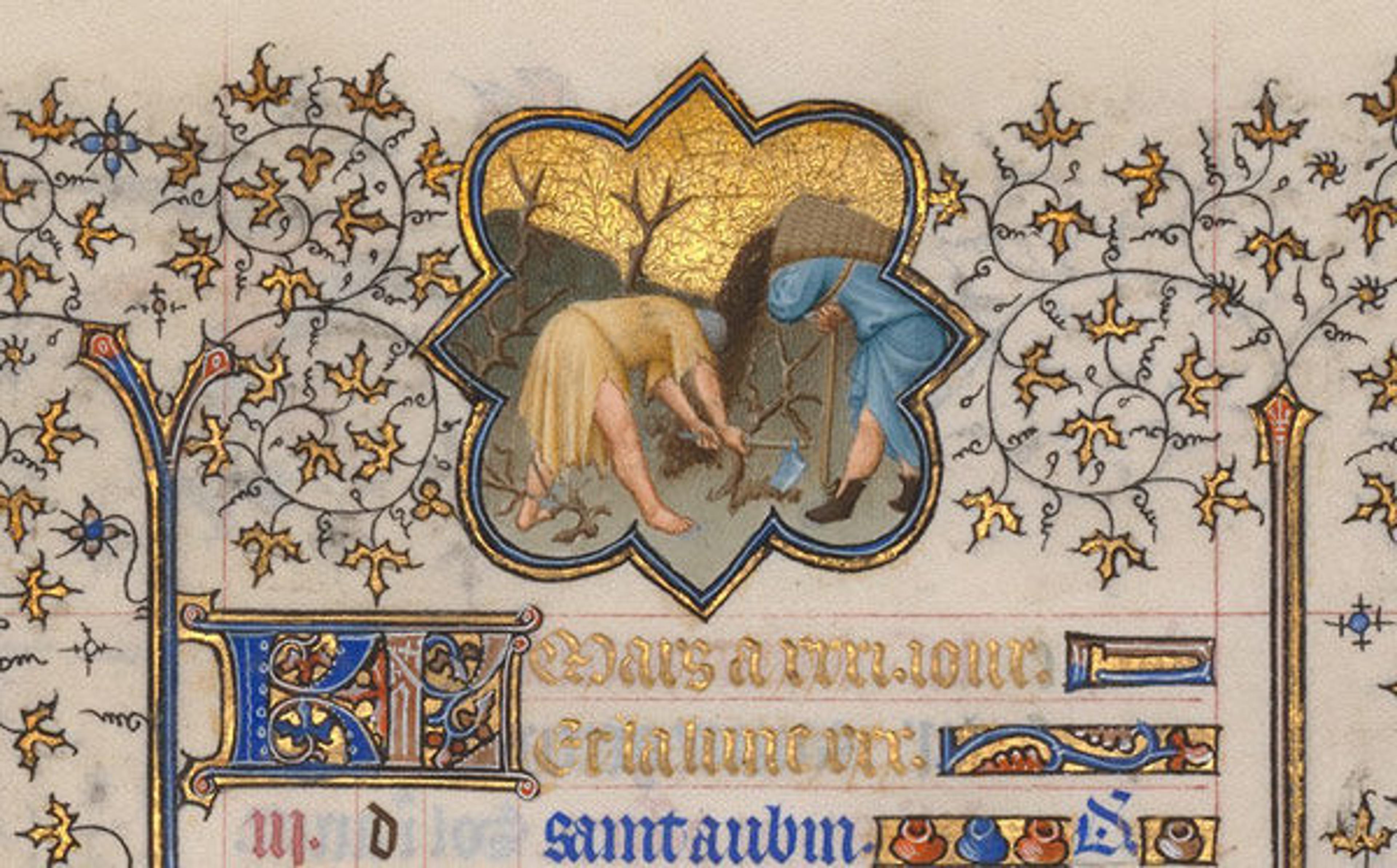

In the medieval calendar, spring also marked the resumption of outdoor activities. Medieval calendars were highly developed systems of timekeeping mainly concerned with marking important feast days for saints. These calendars were executed with a high degree of artistry and attention to detail. Each month was illuminated with the labors associated with the season. This constituted a well-known cycle of tasks that, despite widely different climates, varied little across continental Europe.

The romanticization of the season's labors was especially evident in many of the era's devotionals, known as books of hours. These followed a familiar format, which generally began with a calendar marking the important feast days of each month and the corresponding zodiac sign and illustration of the season's chores (see The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry). Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry (detail), 1405–1408/1409. Made in Paris, France. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

The majority of the tasks depicted are of peasants working the land. While life for those who toiled behind the plow was certainly harsh and unforgiving, especially for a peasant in the Middle Ages, the image wrought in the calendar scenes is one of idyllic solitude. From reaping the autumn's harvest to turning the soil, the season's tasks are imbued with an enduring sense of purpose and well-being that portrays a deep love of nature, albeit a highly manicured and managed one (Henisch 61).

Though the year was sprinkled with periods of respite from working the land, such as January's feast and February's time before the hearth, March saw the gardener busy in the garden. Tasks included manuring and turning the beds and pruning the vines. The gardens department at The Cloisters is also readying for a return to outdoor labors. Sheltered in the greenhouse and behind the seasonal glass panels protecting the arcades of Cuxa Cloister, we continue to tend our collection of tender, potted plants and prick out our seedlings. While the medieval gardener would not have had the advantages of this early start on the season, many of our tasks today remain the same.

Like the medieval gardener, for instance, we sharpen our blades in anticipation of spring pruning. The pollarded crab apples in Cuxa Cloister will be pruned back to their knuckles (see "Woodswoman, Pollard That Tree" [February 25, 2011] on The Medieval Garden Enclosed). Last year's growths, referred to as whips, provide stakes for our taller perennials for later in the summer. Any significant reduction pruning will be undertaken, and fresh mulch will be spread throughout the beds.

A few weeks ago, we tunneled into our cold frames and emerged with the first of our forced potted bulbs, which now grace the arcades surrounding Cuxa Cloister. These fragrant and colorful denizens of spring are a welcome sight. Reticulated iris, miniature daffodils, and hyacinths are among the first to flower. Under the blanket of snow, we know nature is awakening, following its circadian rhythm. Plants, whose cycle is principally ruled by warmth and day length, slowly resume growth.

Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis). Photograph from the Cloisters garden archives

Out in Bonnefont Herb Garden, the snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) are up, but they await the anticipated snow melt to reveal their nodding heads. As a small comfort to those suffering from the long winter, the snow provides many benefits to plants. It serves as a layer of insulation for the soil and moderates fluctuations of temperature, thereby allowing more water to seep into the ground. Winters with low precipitation can be as devastating to plants as summer droughts. (See the daily almanacs for the Northeast.)

Source

Henisch, Bridget Ann. The Medieval Calendar Year. University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Caleb Leech

Caleb Leech is the managing horticulturist at The Met Cloisters.