A Decorated City Restitched in Time

The New York Public Library decorations, Japanese commission, September 27–29, 1917

«For a few days in the spring, summer, and fall of 1917, the buildings and public spaces of New York City were festooned with decorations to welcome the visiting commissions of America's wartime allies—namely the British, French, Italian, Russian, and Japanese war commissions. Watson Library has digitized four albums documenting these visits with photography by the Wurts Brothers Company, whose studio, founded in 1894, specialized in architectural photography.1 The photographs are fascinating both for the historical context in which they were produced—the United States had just entered the war on April 6, 1917—and for the evidence they provide of buildings and monuments which have remained, have been altered, or have disappeared altogether.»

Battery Park decorations, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

City Hall Park decorations, Russian commission, July 6–7, 1917

Though the albums contain no text and minimal captions, contemporary newspaper reports make it relatively easy to reconstruct the movement of the commissions within the city during their stay. Each commission generally followed the same route through Manhattan, commencing at The Battery, where they were met by Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, and from thence up Broadway to City Hall, where reception ceremonies were held in the Aldermanic Chamber. Reporting on the visit of the British and French commissions, the New York Times noted that "City Hall Park had been turned from a place made unsightly by the new subway construction into a beauty spot."2

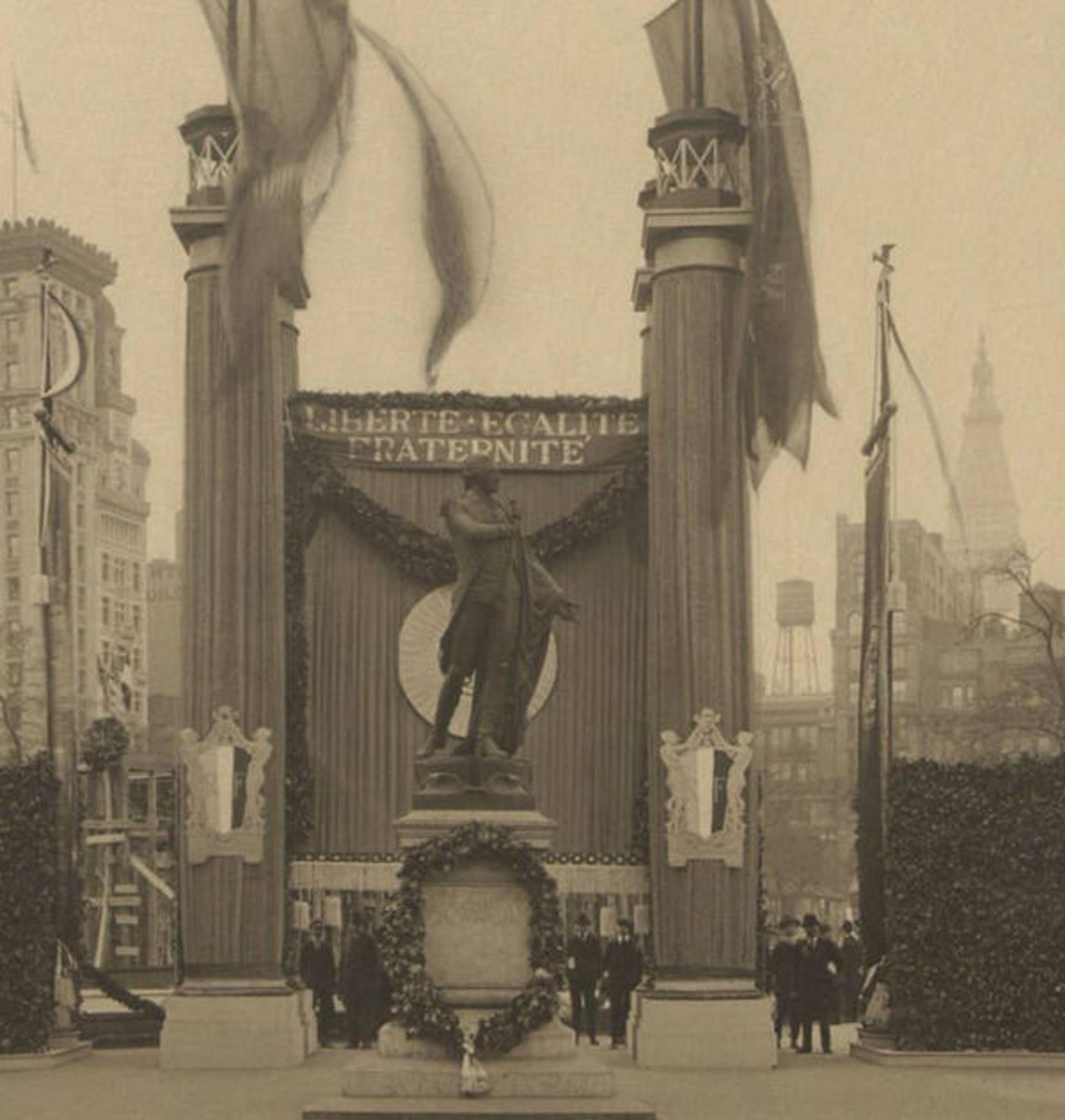

Lafayette statue, Union Square, French commission, May 9–13, 1917

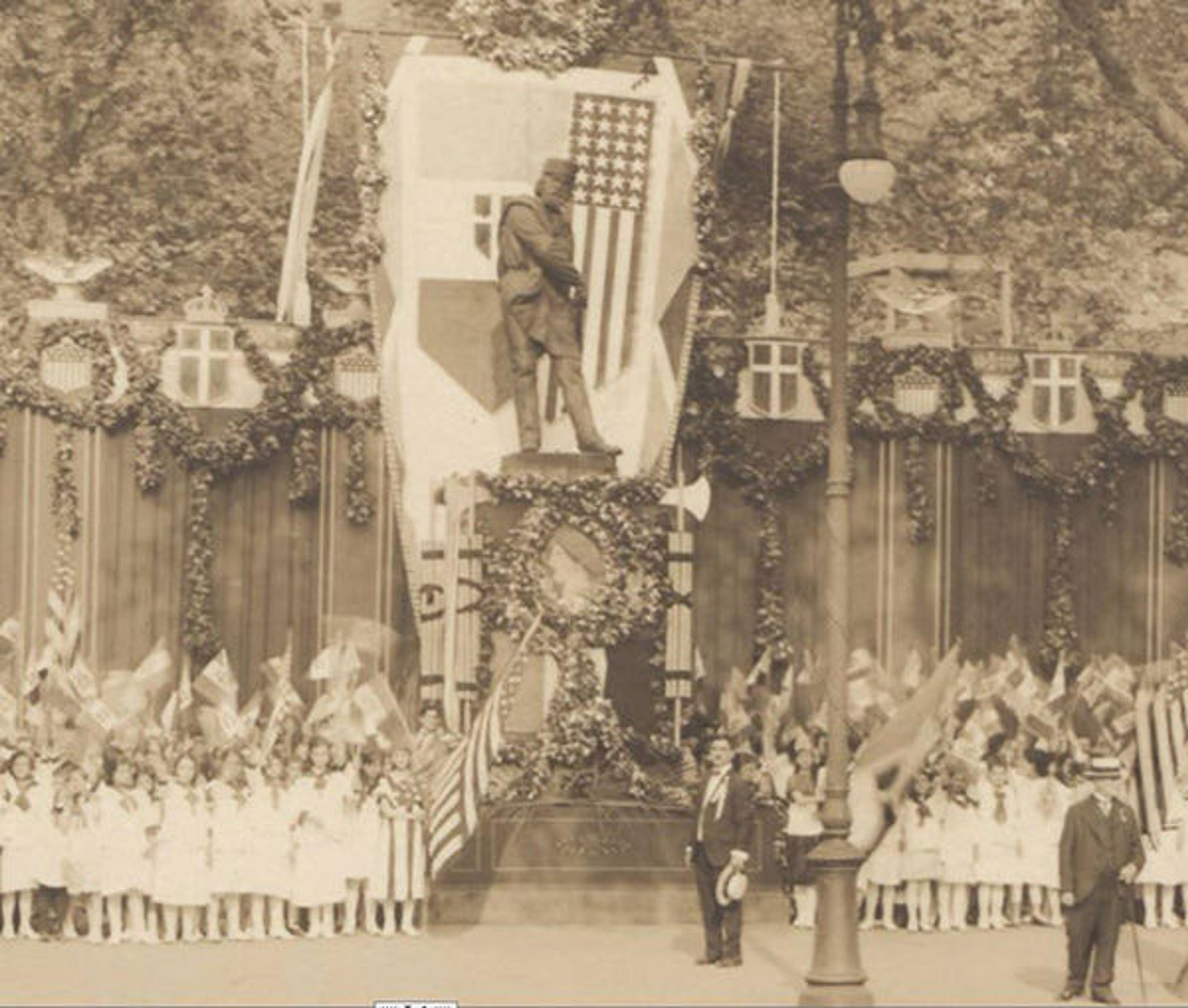

Garibaldi statue, Washington Square, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

The commission route then continued to points north, including Washington Square, Union Square, the New York Public Library, the Plaza Hotel, Columbia University, and Grant's Tomb. Wreaths were placed by the French commission on the Marquis de Lafayette statue in Union Square and by the Italian commission on the Giuseppe Garibaldi statue in Washington Square. Both the Lafayette and Garibaldi statues can still be found in their original locations.

Fifth Avenue decorations, British and French commission, May 9–13, 1917

Fifth Avenue illuminated, Japanese commission, September 27–29, 1917

On their way to the Plaza Hotel, the commissions would have witnessed Fifth Avenue elaborately bedecked with flags, banners, and bunting displaying their national colors, whilst in the evening, they would have enjoyed the Avenue as an illuminated "golden way."3

The Metropolitan Museum of Art facade, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Great Hall, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

Proceeding even further north, the Italian and Russian commissions visited The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The images above show the Museum's facade and Great Hall decorated for the reception of the Italian commission on June 21, 1917.4 The large plaster figures in between the facade's columns were made specifically for the occasion by Paul Manship,5 whose Group of Bears, among other works, continues to delight Museum visitors.

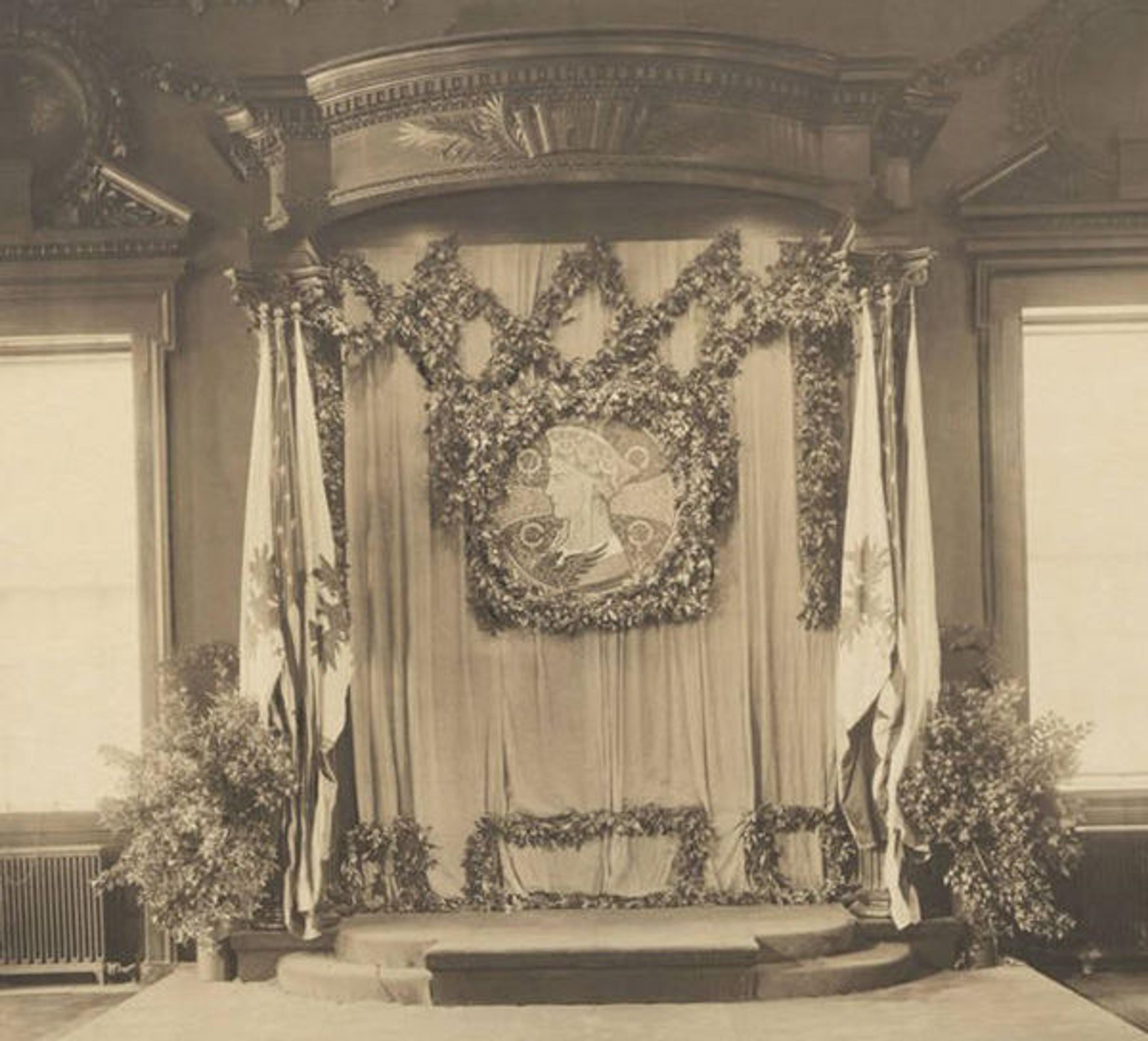

Edwin H. Blashfield, Russian medallion, Aldermanic Chamber, City Hall, Russian commission, July 6–7, 1917

Banquet Hall decorations, Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

In addition to Manship, several other American artists were involved in the planning and execution of the city's decoration. Cass Gilbert, for instance, was the chairman of the city's Committee on Decoration,6 Edwin H. Blashfield designed the Russian medallion that hung in the Aldermanic Chamber at City Hall, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens's figure of Liberty, used on the twenty-dollar gold coin in 1911, was reused for a medal cast on the occasion of the commissions' visits.7 Lloyd Warren, the architect who founded the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design,8 was responsible for decorating the Banquet Hall of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel for the Italian commission dinner.9

Waldorf Astoria Hotel exterior, corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

The Waldorf Astoria was demolished in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building, but in 1917 it stood on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street,10 as seen in the above photograph. Look closely at the two men crossing the street together in this photograph and then at the magnified detail below.

Waldorf Astoria Hotel exterior (detail), Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

The magnification reveals that the blurred outline of the men has been retouched—rather cartoonishly, one might add. Mia Fineman, in her exhibition catalogue Faking It: Manipulated Photography before Photoshop, provides evidence that this sort of retouching was very common throughout photography's history. Fineman writes that "In early twentieth-century newspapers, photographs were altered—and sometimes fabricated in their entirety—to circumvent the camera's limitations as a reportorial tool."11

The Plaza Hotel and square opposite, facing south, Italian commission, June 21–23, 1917

I hope you will enjoy discovering similarly amusing surprises in these albums as you ponder the camera's ability to faithfully document a historically critical moment in time.

[1] "Treasures of The New York Public Library," accessed June 29, 2015, http://exhibitions.nypl.org/treasures/items/show/153.

[2] "Flags Bedeck City as if for Victory," The New York Times, May 10, 1917, 3.

[3] "New York to Greet Envoys," The New York Times, April 26, 1917, 2.

[4] Undated Index Card, [1917], Receptions—1917—Italian (Royal) War Commission, 1917-1918, Office of the Secretery Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

[5] Letter, Cass Gilbert to Conrad Hewitt, January 9, 1918, Receptions—1917—Italian (Royal) War Commission, 1917–1918, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

[6] "New York to Greet Envoys," The New York Times, April 26, 1917, 2.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Oxford Art Online,s.v. "Beaux-Arts Institute of Design," by Elizabeth Meredith Dowling, accessed June 29, 2015, http://0-www.oxfordartonline.com.library.metmuseum.org/.

[9] "Marconi Tells New War History at Italian Dinner," The New York Times, June 23, 1917, 1.

[10] "At Home on 5th Avenue," accessed June 29, 2015, http://www.hosttotheworld.com/omeka/exhibits/show/in-memoriam/fifth-avenue.

[11] Mia Fineman, Faking It: Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 143.

Deborah Vincelli

Deborah Vincelli was the instruction, French and Italian bibliographer, and online resources librarian in Thomas J. Watson Library.