Playing with Paper: Suminagashi and Orizome

Japanese decorative paper techniques using kozo fiber paper and sumi ink

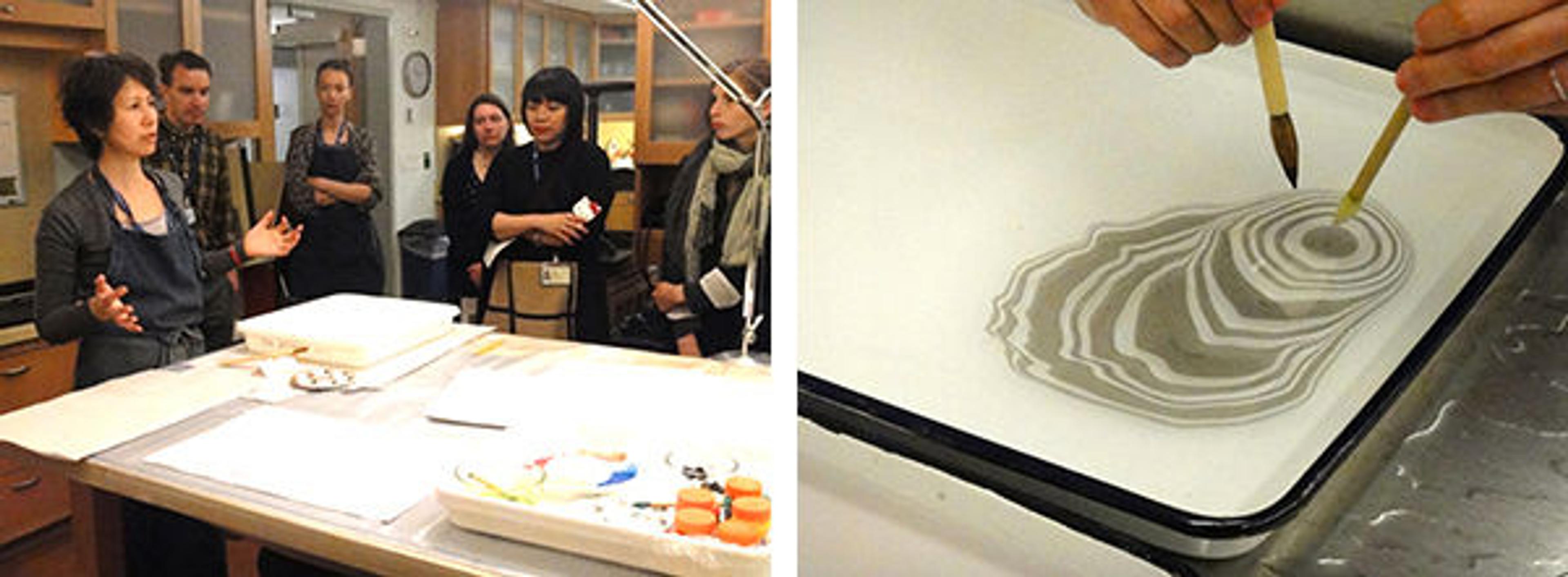

«The Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation hosts regular open houses for all staff, volunteers, and interns who work with the Museum's library collections. While usually focused on preservation-related themes, sometimes we host workshops related to books and paper in general, or to complement a theme or current exhibition. This year one focus has been Japanese books, and Book Conservation staff member Yukari Hayashida recently demonstrated two Japanese decorative paper techniques using kozo fiber paper and sumi ink.»

Left: Yukari Hayashida with Watson and other Museum staff; Right: suminagashi demonstration

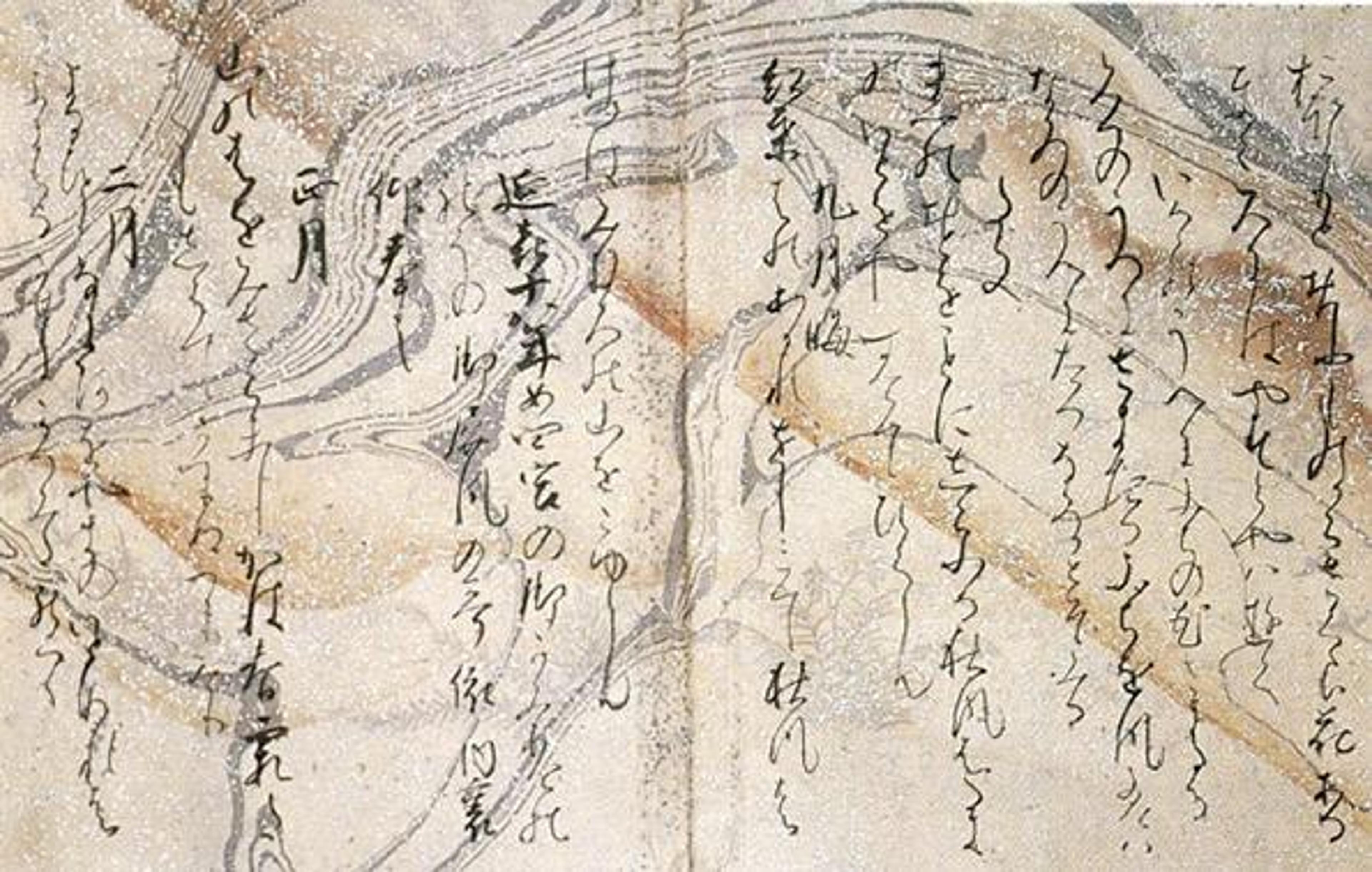

Decorative papers have a long relationship to the world of bookbinding. Marbling in particular is the most common technique associated with European books, often for the pastedowns and endpapers of handmade books. However, many people do not realize that Japanese forms of marbling existed well before the commonly known European, Turkish, or Persian methods. Currently the oldest suminagashi sample dates from the twelfth century, although references to the technique go back to as early as 825–880 c.e. in the poetry of Shigeharu.

Suminagashi is often translated as "floating ink." It has been used for various crafts including not only paper but fabrics, metal, and ceramics. Yukari is one of only a handful of people teaching this technique in this country. So far she has taught classes on it at Penland School of Crafts and, since 2008, at The Center for Book Arts.

Using two brushes with pointy ends, with ink on one tip and water/surfactant solution on the other, they are alternately dipped in the tray filled with water. This creates irregular circles of color and space, which then morph or may be manipulated by blowing or fanning on the subsequent patterns or concentric circles. When ready, paper is then placed carefully on top of the water, peeled off, and the pattern is transferred to the paper. Paper is then left to dry on a rack or flat surface.

Left: Meredith Friedman from the Menschel Photography Library; Right: Meredith, Ben Howell, and Andrijana Sajic

Orizome, which translates as "folded dyeing," is the other technique we played with. While it is most commonly known as a modern technique, simple enough in its basic form to be practiced even by school children, it can also be elaborate, and the craft can be highly developed. The general technique of clamping cloth or paper, itajime, and dyeing in symmetrical folds may go back to the sixth to ninth centuries in China and Japan, even before suminagashi. In any case, it is easy to learn, fun, and the results are often striking.

Paper is folded—usually in a symmetrical or geometric way, sandwiched between two rigid pieces of scrap board—then clamped with a binder clip or similar device, leaving one side of the paper exposed. This exposed side is then dipped directly into wide, shallow reservoirs of ink, or applied with a brush. Multiple sides may be exposed and dyed, depending on the desired effect. The paper is unclamped and left to slightly dry while still wet and fragile, and unfolded before completely dry to avoid the paper sticking together.

Left: Finished orizome; Right: Librarian Tamara Fultz showing off her final product

More on paper techniques and creative folding for orizome can be found in the book Decorative Paper by Diane Maurer-Mathison.

Through the open house we gained an expanded appreciation for decorative paper arts and learned quite a bit from Yukari's demonstration and experience. As you can see from one happily surprised librarian trying this technique for the first time, it was also fun to create these simple designs. The applications and uses are endless.

If you are interested in learning more about suminagashi, the book Suminagashi: The Japanese Art of Marbling: A Practical Guide, by Anne Chambers, is also available at Watson Library.

Jae Carey

Jae Carey is a senior book conservation coordinator in the Thomas J. Watson Library.