Can digital technologies trace the way artists have used raw materials over time and in different cultures? To answer this question, I take a look at cinnabar, a beautiful, historically important mineral that was the subject of a recent exhibition at The Met.

To weave together a history of cinnabar's use in objects at The Met, I sequenced selected objects both geographically and chronologically using two types of cloud-based presentation software with zoom capabilities, Prezi and ChronoZoom. I also looked at other digital technologies to see if they can help us reconstruct color based on revealed pigments and provide viewers with an enhanced immersive experience of color.

A Brief History of Cinnabar

What is cinnabar? The word most likely comes from the ancient Greek κιννάβαρι kinnabari, later romanized to cinnabaris. In Persian, it is known as شنگرف shangarf; in the Arabic world it appears as زنجفرة zinjifrah. Cinnabar, the most common ore of oxidized mercury found in nature, occurs in granular crusts or veins associated with volcanic activity and hot springs. The ruddy hue of this natural mineral pigment embodies the hot and fiery conditions in which it forms.

From left to right: Cinnabar crystal; volcanic eruption; powdered vermilion. Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Cinnabar has been mined and used as a precious resource by many cultures around the globe since at least the 10th millennium B.C. Cinnabar is also known as "vermilion." The two terms are used interchangeably, by both ancient authors and modern scholars, because chemically the two substances are the same (HgS; mercuric sulfide). But "cinnabar" refers to the mineral, while "vermilion" is the pigment. Until the discovery of cadmium red in the early 20th century, vermilion was the most widely used red pigment around the globe, and the most vibrant red.

Anthropologists have long been interested in the role of cinnabar in rituals and other symbolic activities. Research shows it has been used at various times and places to denote blood, victory, success, the duality of life and death, and immortality. For example, the pigment was used during triumphal processions by Romans. It was also applied to skulls and bones as part of burial rituals in neolithic cultures in Anatolia, China, Galilee, Spain, and Syria, and in many cultures of the ancient Americas. Some believe the color was prized because of its vibrant permanence, which is so unlike the blood it visually resembles.

Early Greek Cycladic Sculptures and Other Early Cultures

Cinnabar was known to the ancient Greeks. The Greek botanist Theophrastus described its sources and methods of extraction in the fourth century B.C., but there are also significantly earlier Greek objects with traces of cinnabar at The Met. The surfaces of 14 elegant marble anthropomorphic sculptures and other objects from the Early Greek Cycladic collection were examined by conservators to determine whether or not they were decorated with paint.

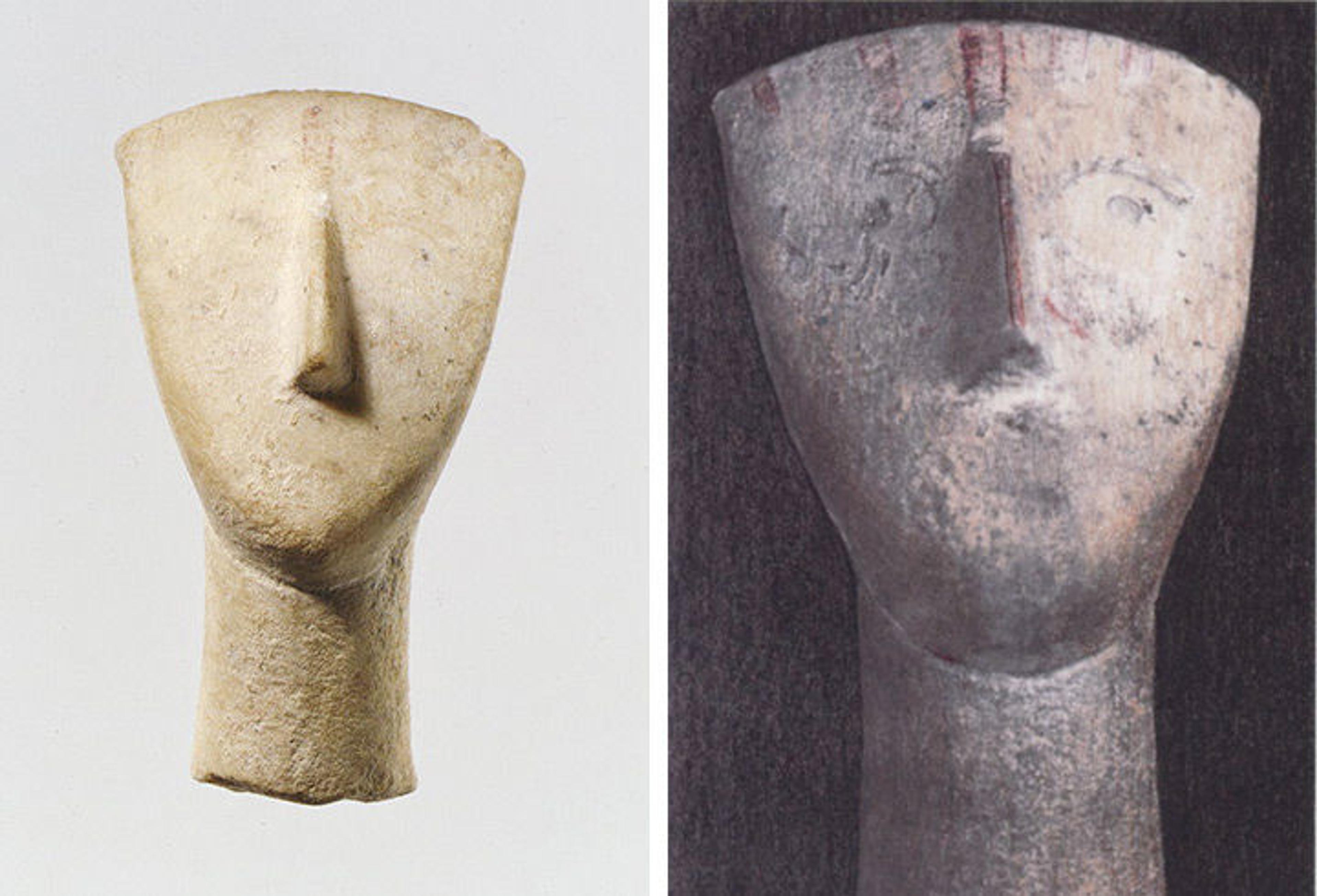

Left: Head and neck from a marble figure, 2700–2500 B.C. Greek, Early Cycladic. Marble, 2 5/8 x 1 1/2 in. (6.6 cm x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Darby Nock Bequest, in honor of Gisela M. A. Richter, 1969 (69.11.5). Right: Reconstruction of color done on photocopy of black-and-white photograph. In Elizabeth Hendrix, "Painted Ladies of the Bronze Age," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 55.3 (1997–98): 7.

Examination under ultraviolet light revealed red pigment on eight of the figures. One of them was found to have six vertical red stripes across the forehead, as well as red paint in other areas, such as along the length of the nose, on the cheeks near the nose, and in an incision on the neck. A sample of this red pigment was analyzed by energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) and found to contain mercury and sulfur as the only major elements; in other words, it is cinnabar.

This Cycladic head is one of the oldest objects in The Met collection known to possess traces of cinnabar. But as the conservator Elizabeth Hendrix has noted, no source of cinnabar has ever been found in the Cyclades. Instead, the closest known sources are in the Almadén region of Spain, in the Balkans near Belgrade, and on the western coast of Turkey. Observing that the Cycladic artist did not use the bright red oxide that was locally available, she wonders if the rarity of cinnabar enhanced the value of the pigment, making it more suitable for decorating the sculpture.[1]

Left: Comb, 13th–11th century B.C. Chinese, Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–1046 B.C.). Jade (nephrite) with traces of cinnabar, 3 x 2 3/8 in. (7.6 x 6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernest Erickson Foundation, 1985 (1985.214.94). Right: Seated figure, 12th–9th century B.C. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Olmec. Ceramic, pigment, 13 3/8 x 12 1/2 x 5 3/4 in. (34 x 31.8 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1134)

Other objects at The Met featuring cinnabar and dating to the first and second millennia B.C. come from cultures as geographically diverse as the Shang dynasty in China and the Olmecs in Mexico (above).

Left: Necklace with pendants, ca. 5th–4th century B.C. Iberian peninsula, Iron Age. Gold, enamel, cinnabar,12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1995 (1995.403.1). Right: Earring, ca. 6th–4th century B.C. Iran, Achaemenid. Gold, turquoise inlay, 1/8 x 1/8 x 2 3/8 in. (.3 x .35 x 6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Norbert Schimmel Trust, 1989 (1989.281.33)

Cinnabar is also known to have been used in jewelry from Iron Age Iberian cultures, and in the Achaemenid Persian Empire it was used as a gemstone bedding to enhance the reddish hue of translucent carnelian stone inlay (above).

The Romans

Like the Greeks, the Romans also used cinnabar. The natural philosopher Pliny the Elder noted that the Romans regarded cinnabar as having great importance and sacred associations. The cinnabar ore used during this period was obtained from Almadén, Spain, the largest mercury mine in the world.

As a pigment, cinnabar possesses many desirable qualities, including a deep hue, good covering characteristics, and compatibility with a number of media, including drying oils, watercolor, egg tempera, and true fresco. Vermilion was first made by heating, crushing, and washing the mined mineral to obtain a relatively pure and usable pigment.

Wall painting from Room H of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 B.C. Roman, Late Republic. Fresco, 73 1/2 x 73 1/2 in. (186.7 x 186.7cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.5)

Natural vermilion was the most expensive pigment used by the Romans for wall paintings, as in this painting from the Villa Boscoreale, on display in gallery 164.

In late antiquity, alchemists interested in turning base metal into gold were also interested in substances like liquid mercury and cinnabar, because of their unusual physical properties. A process for producing a synthetic form of the pigment vermilion was recorded by a Greek alchemist, Zosima of Panopolis, living in Upper Egypt by at least the fourth century A.D., and by a Persian alchemist, Jabir ibn Hayyan, around the eighth century A.D.

Synthetic vermilion was made by either a dry or a wet method. The dry method—possibly invented first in China as early as the fourth century B.C.—consisted of heating mercury and sulfur in a sealed container. In the East, cinnabar was added as a colorant to the sap known as urushiol to form lacquer work.

Tracing Cinnabar and Vermilion at The Met

What digital tools can help us find cinnabar?

By searching in The Met's online collection and the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, one can identify many art objects known to incorporate cinnabar or natural or synthetic vermilion. But there are other instances that are either not yet confirmed by scientific testing or not accessible by computerized search results. For example, the online collection has hundreds of objects associated with the phrase "red lacquer," a material that we know was commonly made with cinnabar.

Upper left: Storage case (Karabitsu), 1422. Japanese, Muromachi period (1392–1573). Red over black lacquer on wood with gilt bronze fittings (Negoro ware), H. 13 in., W. 15 3/4 in., L. 22 1/8 in. (33 x 40 x 56.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.2.9a, b). Upper right: Dish with peonies, 14th century. Chinese, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Carved red lacquer, H. 1/4 in., Diam. 6 3/4 (.6 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.70). Lower: Bursa reliquary, 10th century. North Italian. Bone, copper-gilt, wood, 7 3/4 x 7 1/2 x 3 1/4 in. (19.7 x 18.6 x 8.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1953 (53.19.2)

A simple search for "cinnabar" will not retrieve these objects, because the computer won't know to link red lacquer and cinnabar unless both terms have already been included in the object's description and metadata. The same is undoubtedly true for many other objects at The Met, unless the pigment is specifically described, like the vermilion identified on the Bursa reliquary.

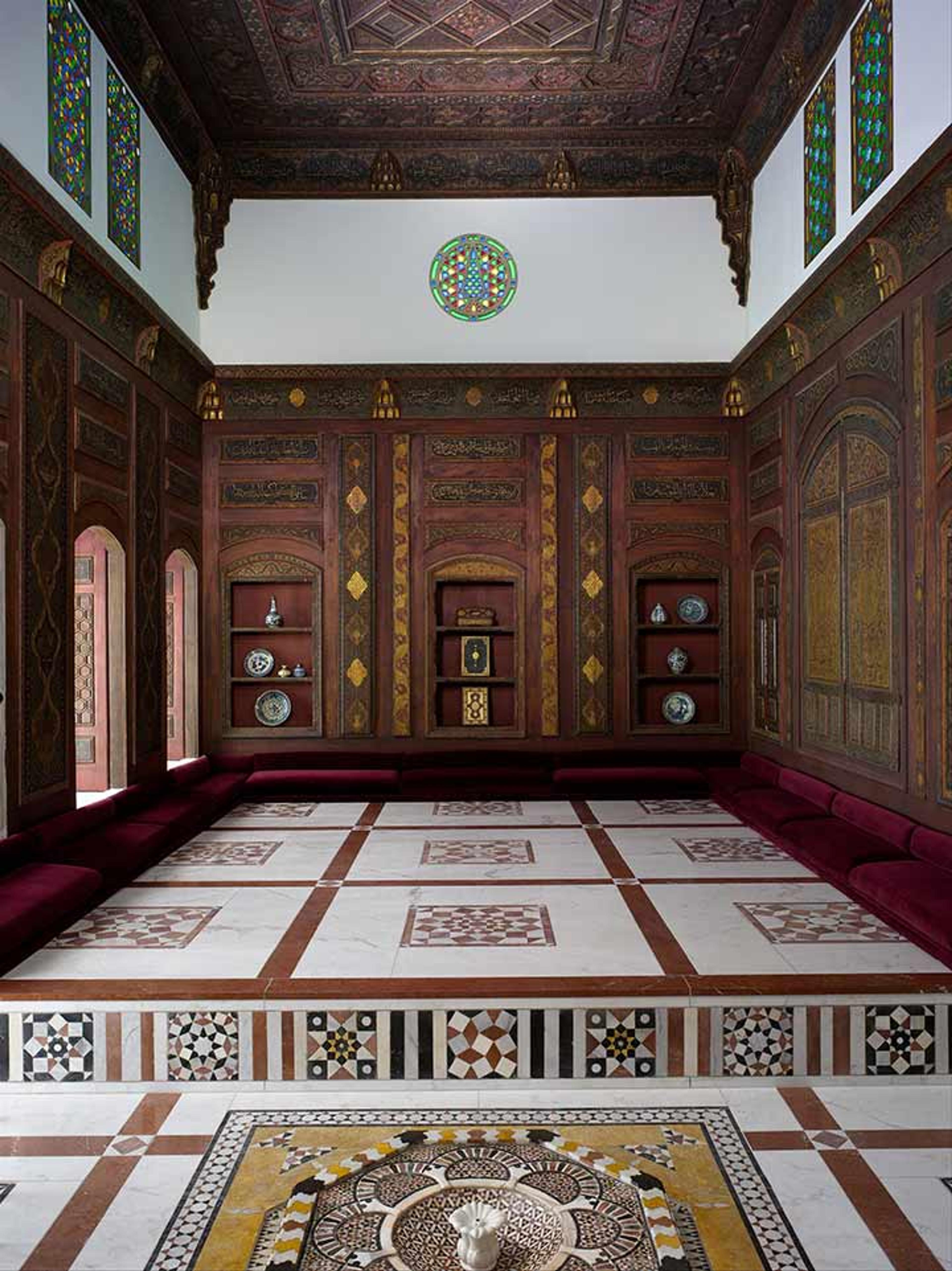

As a result, my computer search had to be supplemented by traditional research. In this process, I learned that vermilion was one of several red pigments identified by means of Raman spectroscopy, among other tests, on the painted surfaces of the Damascus Room, an early 18th-century reception room that belonged to an affluent family living in Syria, installed in gallery 461.

Damascus Room, A.H. 1119/A.D. 1707. Syria, Damascus. Wood (poplar) with gesso relief, gold and tin leaf, glazes and paint; wood (cypress, poplar, and mulberry), mother-of-pearl, marble and other stones, stucco with glass, plaster ceramic tiles, iron, brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Hagop Kevorkian Fund, 1970 (1970.170)

Many of the red areas on the walls were painted using a thin layer of vermilion in an egg-tempera medium over a bright orange-red lead underlayer. Orange areas of selected elements were found to have vermilion and orpiment, a rare, orange-to-lemon-yellow arsenic sulfide mineral pigment.[2]

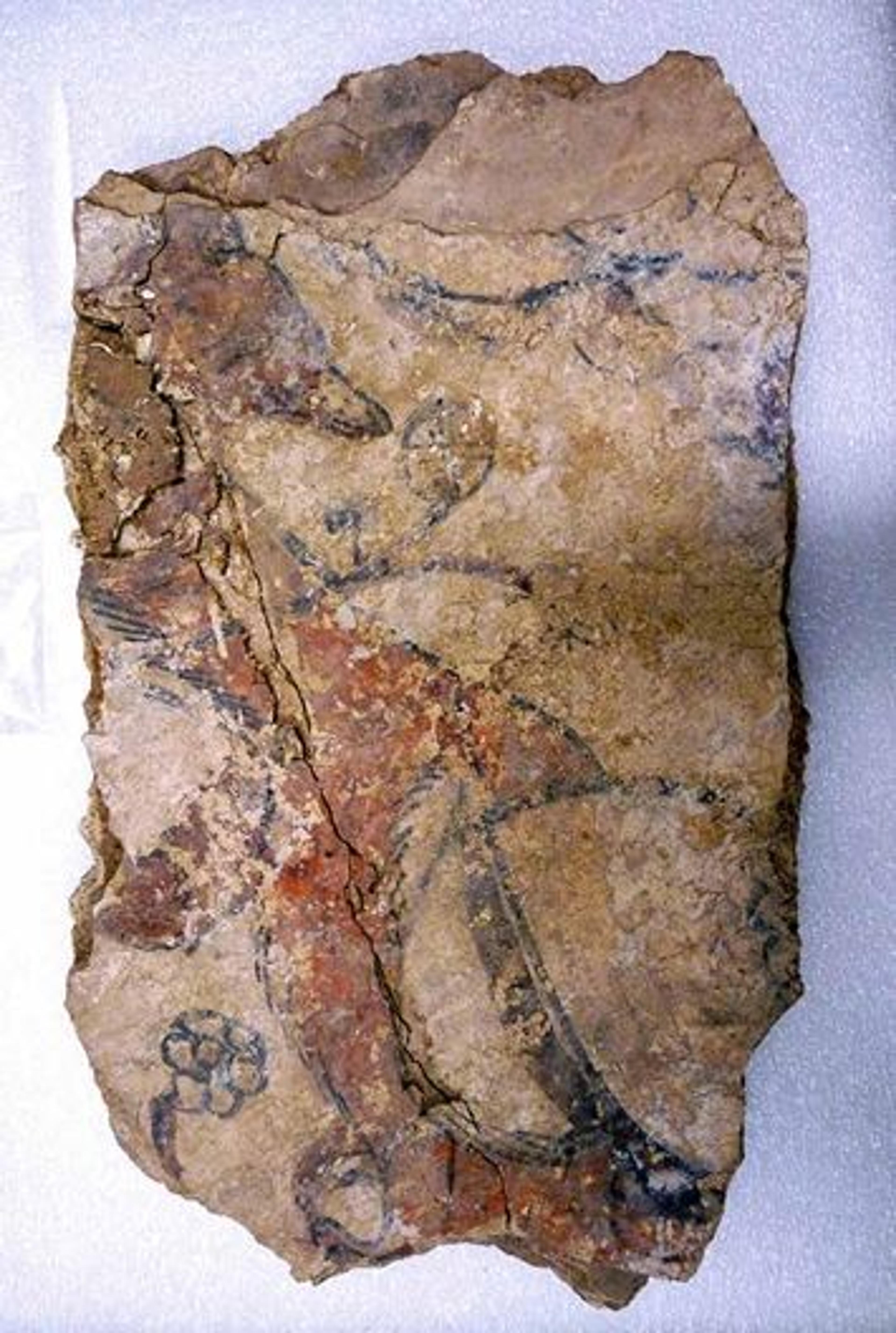

Left: Fragment of a wall painting with a fox or a dog (and painted layers), 12th century. Excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Lime plaster; painted. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1948 (48.101.302)

Vermilion has also recently been identified on fragments of carved stucco, wall painting, and terracotta friezes, dating to the 12th century, from Nishapur in northeastern Iran.[3]

Scientific testing is necessary to identify pigments, but the results of such tests are not always available online. My own search was aided by the scientific test results of an ongoing conservation project at The Met that traces the use of cinnabar in South America.

Left: Kero, 17th century. Peru. Quechua. Wood (Escallonia), pigmented resin inlay, H. 8 5/8 in. (21.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Arthur M. Bullowa, 1993 (1994.35.26). Center: Kero, late 16th century. Peru. Quechua. Wood (Escallonia ?), pigmented resin inlay, H. 8 5/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Arthur M. Bullowa, 1993. (1994.35.14). Right: Kero, 16th century. Peru. Quechua. Wood, pigmented resin inlay, H. 7 3/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Arthur M. Bullowa, 1993 (1994.35.12)

In this project, beautiful drinking vessels called qeros (or keros), produced by both ancient cultures and colonial subjects such as the Quechua, are the subject of an inter-museum technical study that uses X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis to identify crystalline materials, including pigments such as cinnabar. The cinnabar found on these vessels may initially have been obtained at Huancavelica, Peru, the largest mercury mine in the Americas.

I learned that scientific analysis provides the only reliable method of accurately identifying the pigments applied to an object. The test findings can then be amplified and confirmed by scholarly research on similar objects. Additional scientific testing of objects in The Met collection could identify many more objects containing cinnabar, and reveal much about ancient trading patterns and cross-cultural influences over the millennia.

Using Technology to See Cinnabar

After my computer search and consultation with conservators to identify objects containing cinnabar, I used two online apps, Prezi and ChronoZoom, to create a timeline showing how cinnabar and vermilion were used in objects at The Met by almost two dozen cultures, on many continents, from at least the third millennium B.C. to at least the mid-19th century A.D. My analysis also examined possible sources of that cinnabar. If you explore technologies like these, which provide a means of accessing and analyzing related art objects in context, I think you will find them to be innovative, meaningful, and fun!

In exploring the story of cinnabar at The Met, I was also inspired by several conservation projects that have used various technologies to reveal and reconstruct objects containing cinnabar or vermilion. These projects ranged from the Cycladic Greek sculptures discussed above to a Cypriot sarcophagus and Roman frescoes. I began to think about how technology could be used to further enhance viewers' understanding and appreciation of cinnabar in the collection.

The Amathus Sarcophagus, 2nd quarter of the 5th century B.C. Cypriot, Archaic. Hard limestone, 62 x 93 1/8 x 38 1/2 in. (157.5 x 236.6 x 97.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76 (74.51.2453)

One of the jewels in The Met's Cypriot collection is the Amathus Sarcophagus. Most likely produced for a local king, the sarcophagus was brought to New York by General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who became The Met's first director in 1879. The sarcophagus is unique due to its monumentality and the relatively good preservation of its polychromy.

Conservators have analyzed minute pigment samples using a variety of investigative tools including polarized light microscopy (PLM), X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS). Mercuric sulfide has been positively identified in the red pigment—more cinnabar.

Watercolor reconstruction of the painted decoration on the Amathus sarcophagus, from Cyprus, ca. 475 B.C., with a key to the colors. In Elizabeth A. Hendrix, "Polychromy on the Amathus Sarcophagus, a 'Rare Gem of Art,'" Metropolitan Museum Journal 36 (2001), plate 1, p. 9.

In her study of the decoration of the sarcophagus, conservator Elizabeth Hendrix notes that "almost every centimeter of stone was highly colored. . . . The background of each side was patterned in blue and red, and the bands of decoration above and below the figural scenes were also painted in contrasting shades."[4] She has reconstructed the elaborate polychromy in a series of watercolors, displayed in gallery 174, that show the original appearance of the sarcophagus and each of the pigments identified, including an abundance of cinnabar. The effect is one of a vivid, triumphant funeral procession.

These painstaking efforts by the Department of Objects Conservation have allowed visitors to appreciate this object's original appearance. More recent technology, such as an online presentation of a 3D scan with an integrated audio feature or the type of technology used in The Met Media Lab's Color the Temple project, might further enhance audience appreciation of the original polychromy of the object.

The Villa Boscoreale Cubiculum

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 B.C. Roman, Late Republic. Fresco. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.13a–g)

The Met has numerous wall frescoes from the Villa of Boscoreale north of Pompeii, which was excavated in 1899–1900. These frescoes are of exceptional quality and feature an extensive and elegant use of cinnabar, particularly those in the cubiculum (bedroom) that was formerly displayed in The Met's Great Hall for 40 years (now installed in gallery 165).

A major conservation project undertaken in 2007 by The Met, in collaboration with King's College, London, was accompanied by a computer construction that created a 3D virtual model of the entire villa.[5] This stationary virtual model allowed the public to imagine what it would be like to see the frescoes when moving through the rooms, but did not allow viewers to see the details of cinnabar's use in the frescoes up close with an immersive experience.

Today, this digital presentation might be enhanced by using 360-degree video that would allow a viewer to observe all of the room's details in an immersive experience, or perhaps even to move through the virtual model of the villa using a smartphone.

Back wall of the Damascus Room

Similarly, 360-degree technology or interactive virtual-reality technology (such as I experienced at the Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures exhibition at The Met Cloisters) could be used to enhance the presentation of the Damascus Room by supplementing the stationary touch screen, adjacent to the room, which reconstructs the original colors hidden under the varnish, including vermilion.<

Looking towards the Future

In the future, museums like The Met will be able to meld their collections with new digital technologies that make them even more accessible to visitors of all ages and cultures. Such technologies may allow us to trace the way materials such as cinnabar and vermilion were used by artists across time and geography. Technology may also help us to digitally reconstruct areas where the original colors have faded or are almost totally lost. Such tools will greatly enhance our understanding and appreciation of the Museum's extraordinary collection.

Jean-François de Lapérouse, a conservator in the Department of Objects Conservation at The Met, was the inspiration for this project on cinnabar and served as a consultant for the project.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth A. Hendrix, "Painted Ladies of the Bronze Age," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 55.3 (1997–98): 8.

[2] Mechthild Baumeister, et al., "A Splendid Welcome to the 'House of Praises, Glorious Deeds and Magnanimity,'" Studies in Conservation 55, suppl. 2 (2010), 129–30.

[3] Parviz Holakooei and Jean-Francois de Laperouse et al., "Early Islamic Pigments at Nishapur, North-Eastern Iran: Studies on the Painted Fragments Preserved at The Metropolitan Museum of Art," Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2016). doi: 10.1007/s12520-016-0347-7.

[4] Elizabeth A. Hendrix, "Polychromy on the Amathus Sarcophagus, a 'Rare Gem of Art,'" Metropolitan Museum Journal 36 (2001): 44.

[5] See Bettina Bergmann, Stefano De Caro, Joan R. Mertens, and Rudolf Meyer, Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010).

Additional Resources

Video presentation by the author, Ellen Spindler, at The Met Media Lab Expo 2015

Department of Asian Art. "Lacquerware of East Asia." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (October 2004).

Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Early Cycladic Art and Culture." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (October 2004).

Easthaugh, Nicholas et al., Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments. Oxford: Elsevier, 2013.

Gettens, R. J., R. L. Feller, and W. T. Chase. Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics. Vol. 2. A publication of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and Oxford University Press, 1993.

Martin-Gil, J. et al., "The first known use of vermilion." Experientia 51 (1995). doi::10:1007/BF01922425.