No Dogs Allowed: How William Wegman Broke the Rules of Conceptual Art

William Wegman (American, born 1943).New & Used Car Salesman (still), 1973. Single-channel digital video, transferred from Sony AV 3600 1/2-inch video tape, black-and-white, sound, 1 min., 32 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Wegman and Christine Burgin, 2017 (2017.210.87). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

The mid-century East Coast variety of Conceptual art was all about rules—dictums defined the idea, like lines in a drawing. Artists like Sol LeWitt established procedures through which a work of art could be reproduced by anyone with the instructions to make it. Others, like Adrian Piper, posited rules to a viewer who, by following along, participated in an artistic act. This notion that an idea could be defined as a work of art was seen as radically democratic and anti-authorial. It was hailed as a "dematerialization of the art object" by critics like Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, and a challenge to the prevailing mythology of the artist's hand. But for all this air of iconoclasm, it took a real jokester to truly turn these paradigms around, to show how opaque and forbidding orders could actually reinforce stoic notions about art.

Or so might argue Doug Eklund, curator of Before/On/After: William Wegman and California Conceptualism, on view through July 15, 2018. William Wegman and his California compatriots—artists such as John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, Vija Celmins, Douglas Huebler, and David Salle—are represented in this small survey of Conceptualism as it manifested on the left coast, where it took on a decidedly whimsical air. Visitors to the exhibition in gallery 851 will notice the space's new layout—the middle third of the gallery has been reinstalled as a small theater, in which Wegman's video works from the 1970s play, a selection of the 174 videos gifted to the Museum by the artist last year.

As Eklund and I spoke in the galleries, we raised our voices over the sounds of frequent laughter and the barking of Man Ray, Wegman's Weimaraner named after the famed Surrealist, and a frequent collaborator in the artist's work.

William Wegman (American, born 1943). Born with No Mouth (still), 1972–73. Single-channel digital video, transferred from Sony AV 3600 1/2-inch video tape, black-and-white, sound, 1 min., 2 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Wegman and Christine Burgin, 2017 (2017.210.64). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Will Fenstermaker: Can I start by saying that this exhibition is hilarious?

Doug Eklund: To hear people laughing in this gallery is very heartening. To have that spirit in the Museum in these anxious times. Even though, you know, there's a layer beneath the comedy that's kind of dark. But good comedy is often laced with issues of failure and sadness, loss and abandonment.

Will Fenstermaker: The video that was playing when I walked in was Born with No Mouth, where William Wegman is earnestly explaining that his grandfather's mouth was transplanted onto his own face. It's funny, but you know. . . .

Doug Eklund: [laughs] It has a real bite at the center of it.

Will Fenstermaker: Okay, so let's talk about what's going on in here. Before/On/After includes a number of works gifted by William Wegman, but it's not really a show about Wegman. There are lots of other artists in here.

Doug Eklund: We toyed with the idea of just presenting William Wegman at The Met. I've always been a fan, and early Wegman photo pieces have been a gap in our collection. They're part of my twenty-year acquisition plan of building the collection in areas where contemporary art can be represented through photography—artists like Lucas Blalock and Ann Hamilton.

But what happened was that I laid out our Wegmans and I pulled works by artists who were working in California at the same moment, in the early seventies. That was my original idea—to juxtapose the Wegmans with other works, Ed Ruscha and that kind of thing. I showed it to Bill and Christine Burgin, his wife, and they said, "This is great, but. . . ."

Installation view of Before/On/After: William Wegman and California Conceptualism

Bill and Christine were very happy that we were interested in his early work, particularly his videos, and so they donated work to fill out the show and flesh out our holdings of his early work. We received a gift of eight or nine works on paper from Bill and Christine, gifts to make The Met's collection of Wegman more rounded. They also helped me pick other works by other artists.

Will Fenstermaker: I didn't know that they helped select some works in the show. There's that joke that when artists donate their canonical works, they'll tuck in some of their more esoteric projects and sneak them into a collection that way. But this is clearly not that. It's all early work, which you were seeking out. Like, there are no Polaroids of Fay Ray or skits from Sesame Street here.

Doug Eklund: This show is about Wegman becoming William Wegman. We're really interested in honing in on this big, singular leap at the beginning of his career. Not all the works are by his friends. They're people who were working at the same time, but then Robert Cumming is a really interesting artist who nobody knows about. There are some connections and certain things I didn't realize until Bill told me about them—like that Vija Celmins was incredibly close with Wegman at that moment.

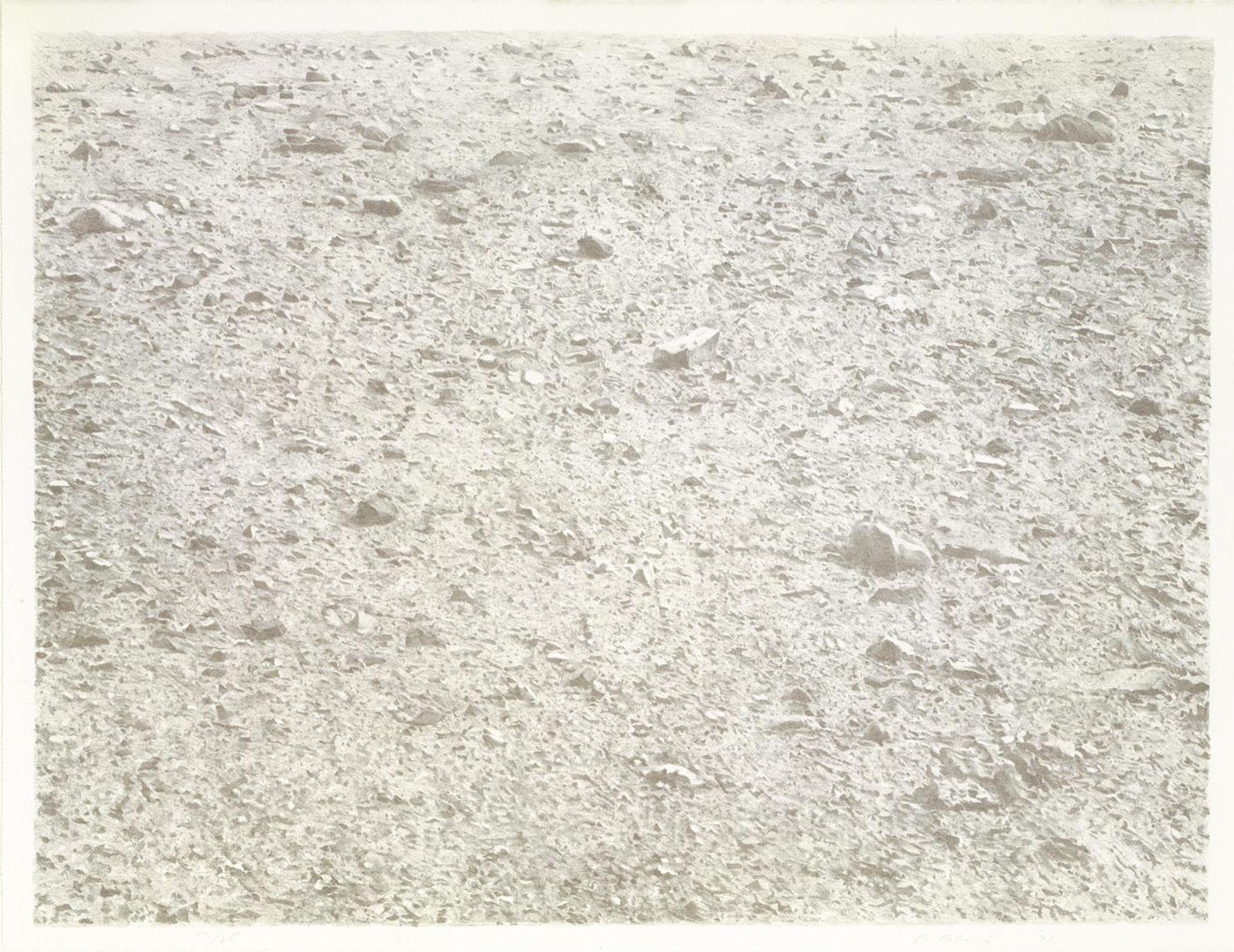

Will Fenstermaker: Her print is another surprising work to see here. I didn't know that they knew each other, and it kind of stands apart as quieter than a lot of the other works.

Vija Celmins (American, born Riga, Latvia, 1938). Untitled (Desert), 1971. Printed by Ed Hamilton (American, born 1941). Published by Cirrus Editions. Lithograph, 22 3/8 x 29 in. (56.8 x 73.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, John B. Turner Fund, 1972 (1972.501.5). © 2010 Vija Celmins

Doug Eklund: Oh yeah, absolutely. But when you look at her print next to Inverted Plywood, the connection makes sense. They share that idea that a Conceptual work of art is always displaced; Wegman's sort of referring offstage to these ideas of orientation, up and down, and Celmins is very much about that too.

Will Fenstermaker: About displacement?

Doug Eklund: Yeah, and also the disorientation of what's up and down, which is present in the desert ground and places like that. So we were able to put together relationships that I don't think most people even knew.

One thing I've noticed over the years, thinking about changes in viewing patterns or changes in audience, is that twenty years ago there was more than just a general interest in Conceptual art. People knew more about difficult Conceptual art. And now things have just turned 180 degrees so that people are really interested in color pictures of recognizable things that they can relate to their Instagram feed.

Will Fenstermaker: Images that have immediacy.

Doug Eklund: Right. These videos are from a different age, when art was meant to be difficult and challenging and not look like art or assert itself in that self-referential way. It's all tied up with this anti-artistic, anti-market use of photography and video. These videos weren't limited editions to be sold for $100,000—they were stored in libraries. You could take them out on tape. It's very weird to be doing a show like this at this moment.

Will Fenstermaker: So what was going on in the seventies on the West Coast? I understand this was when the art scene there really came into its own, started defining itself along its own terms.

Doug Eklund: You know, it was really this group of artists. These are the founding fathers of West Coast Conceptualism. Even moving to Los Angles instead of New York, as Bruce Nauman and Wegman did around 1970, was uncommon. They both studied at Wisconsin-Madison—Nauman '60 to '64, and Wegman taught there in the late sixties—and they both wound up in LA and were in the same basketball games and all of that.

The art that was being developed in LA had an innate relationship to New York, almost as if these artists were trying to deal with the view that New Yorkers had of LA—this idea of LA as a total backwater populated with dumb blondes and all of that condescending dismissiveness. That kind of self-aware dumbness is inherent in the work of these artists.

And also, failure as an aesthetic strategy. You'll see that idea of failure in the videos and in John Baldessari's work, which I wrote about in an essay for the Baldessari retrospective in 2010.[1]

Basically, this show presents a view of Conceptual art as it developed on the West Coast in response to the East Coast, where it was this very mandarin, severe form of image-text combination. LA artists zeroed right in on the soft spots in New York's version of Conceptual art, particularly in that much more could be done with language, and better.

Will Fenstermaker: Who were some of the artists they were looking at in New York?

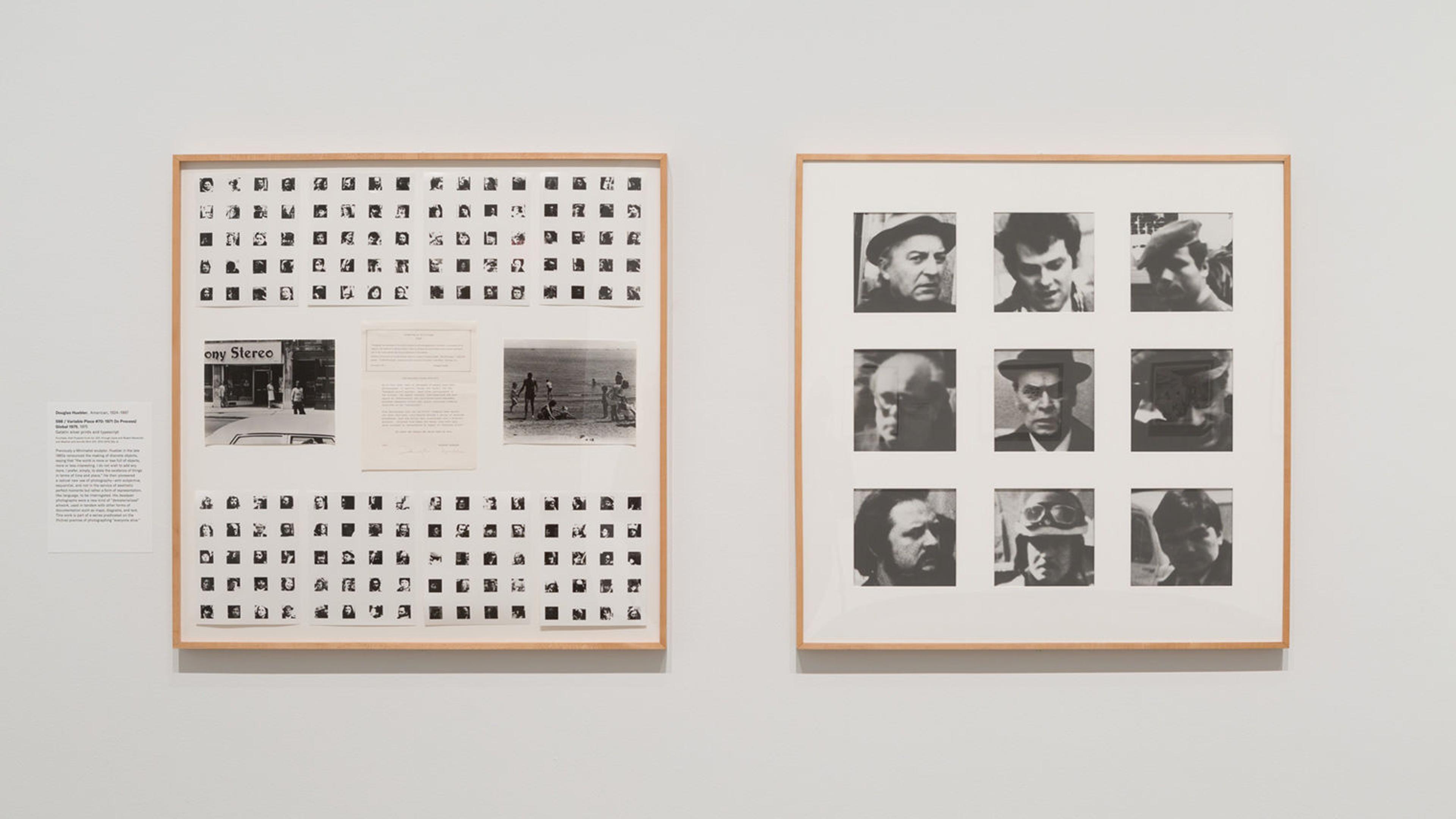

Doug Eklund: Oh, it's unfair of me to say, but Joseph Kosuth is sort of the template—a fine artist, but his rigor and philosophical showiness made him sort of a representative of a serious art. I should say that Douglas Huebler, who's in this show, was also part of that New York group, but I'm looking at him as the teacher who followed Baldessari at CalArts. He was just as influential as Baldessari on the next generation of people, like Mike Kelley and so forth. Even early on he was doing things in a much more complicated way than, say, Hans Haacke—whom I also love for different reasons.

David Salle (American, born 1952). Untitled, 1973. Four gelatin silver prints with affixed color advertisements, each 24 x 20 in. (61 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jennifer Saul Gift; Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel; and The Robert A. and Renée E. Belfer Family Foundation Gift, 2008 (2008.345a–d)

Huebler's work here is so complex and head scratching. You can look at David Salle for a clue to figuring it out. Salle was very insistent that because of the combination of the drink labels and the black-and-white photographs, we have to take the artist's word that that specific drink is in that cup. He's playing with the ways that we put meaning together and with the underlying suppositions of art.

Will Fenstermaker: And creating a kind of meaning that may or may not be true, but that exists for real in your head.

Doug Eklund: Right, it's a grand fiction. So with Huebler, this project is his attempt to depict everyone alive.

Will Fenstermaker: Obviously, he failed.

Doug Eklund: It's inherently an unfinishable project. It was never serious as an end, but it's very serious as a way to frame questions. On the left, he's showing you the kinds of images he uses to make these grids like the one on the right. His sorting device is a maxim that defines the subject as at least one of the nine depicted. It's so open-ended. It could be all nine of them, it could be one. . . .

Douglas Huebler (American, 1924–1997). 598 / Variable Piece #70 : 1971 (In Process) Global 1975, 1975. Gelatin silver prints and typescript, 37 x 74 in. (94 x 188 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Stephen and Jennifer Rich Gift, 2012 (2012.32a, b). © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

So the work ends up really being about faces and the way that we fill them in just by their look. That's essentially what we do with photographs—we project into these things. Like, to me, these people all look like war criminals. Huebler's taking apart how quickly we make assumptions based on surfaces and photographs and that kind of thing. And that idea of belief was hugely important on artists like Mike Kelley.

As to why that happened on the West Coast as opposed to the East Coast, I don't know. On the East Coast, it was just this very dry, informational style, whereas the LA artists dealt with narrative in a way that was incredibly complex. Their image-text combinations bring in the world and have emotional resonances that are just not always present in New York Conceptualism.

This idea of belief systems also moves into the show I'm working on now.

Will Fenstermaker: And what's that?

Doug Eklund: Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at The Met Breuer this September. How you feel about conspiracy theories is such a tag of your ideological stance. When I show it to people, sometimes they say, "Well, this isn't what I think of as conspiracy."

Will Fenstermaker: Let me tell you about the real conspiracy.

Doug Eklund: Yeah. My co-curator on the show, Ian Alteveer, is writing this essay on CalArts for the catalogue in which he talks about California as the land of subcultures. In 1970, there were something like three thousand cults in Los Angeles. If you think of counterculture as being this dismantling of hierarchies and conventions, then what these artists did was say, "Not so fast, counterculture! There's no tabula rasa; there are always conventions."

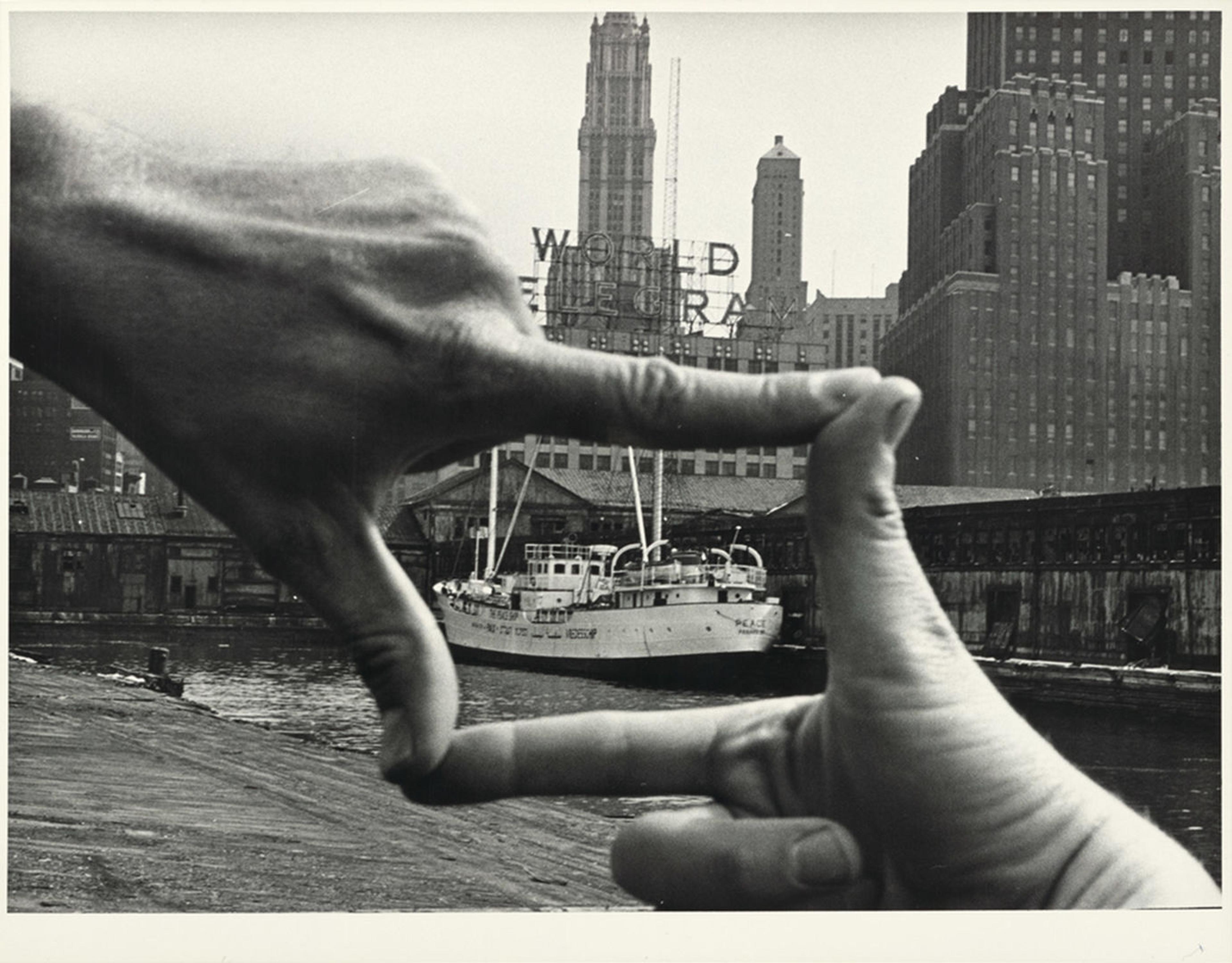

Baldessari is all about that. In Hands Framing New York Harbor, he's stepping in between you and the picture to say that we're always making pictures.

John Baldessari (American, born 1931), Harry Shunk (German, 1924–2006), and János (Jean) Kender (Hungarian, 1937–2009). Hands Framing New York Harbor, 1971. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 7 1/16 in. (25.4 x 18.0 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1992 (1992.5111). Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

Will Fenstermaker: Thinking of this immediacy, though: One of the things that, at least to me, has always distinguished Wegman is the lucidity of his work. I mean, Ruscha, Baldessari, they're also sometimes funny; they can have similar senses of humor. But their humor is often dependent on the viewer having some specialized knowledge about the art they're referencing.

Doug Eklund: An inside joke.

Will Fenstermaker: Yeah. But with Wegman, it's not an inside joke. Or rarely is.

Doug Eklund: Well, actually, it's always both. That's the thing. In Wegman's work, he's also making those references, but they're an extra layer. I think what you're picking up on are the different levels to Wegman's work. If you watch the videos and you're aware of post-minimalism and all that, you can say, "Ah, that's a Lynda Benglis joke." That's always part of it; but on top of that, you're right, is an immediate layer where you don't have to have that knowledge to "get it."

Wegman is so good at creating this totally elemental, simple, clear image that nevertheless messes with your mind. Like, Light Off / Light On is a work that tempts you to start looking for the differences between the two photos. But it also jumps to another level where it refers to the most minimal action / nonaction you can take, which is that simple switch flip. There are a lot of paired images here that play with that sameness and difference, or that play with the idea of staging photographs for the camera, staging an event. Obviously, that reverses that whole Cartier-Bresson notion of the perfect moment, where you're looking for the unique thing.

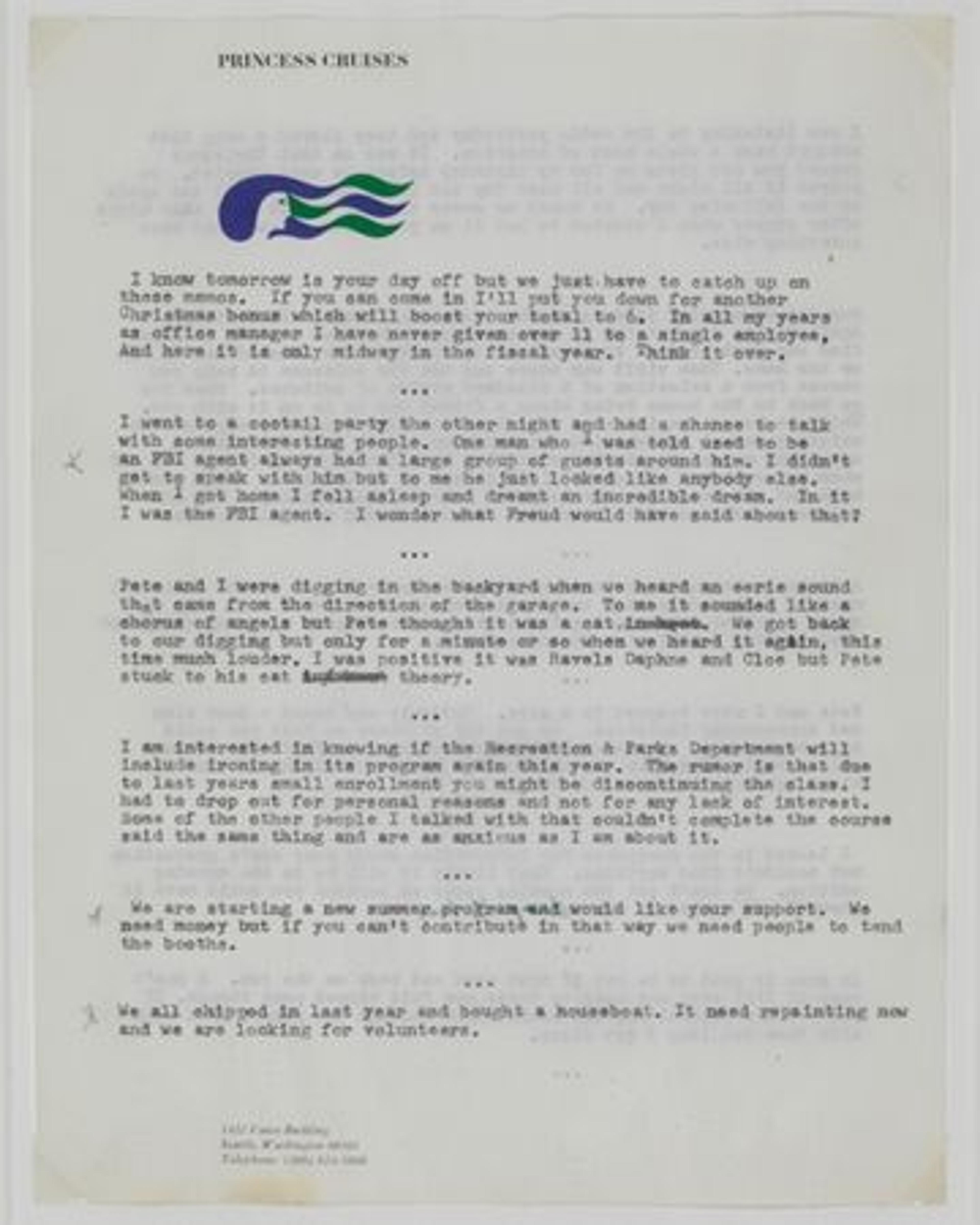

Left: William Wegman (American, born 1943). Untitled ("I know tomorrow is your day off . . ."), 1970–71. Typewritten text and graphite on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Wegman, 2017 (2017.430.7a, b). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Similarly, you know Lawrence Weiner and his fantastic books, which are filled with phrases that refer to an action that anyone can do. They're democratic and anti-authorial in the same way as Wegman's Typewriter Drawings. Even though they're text on stationary, Bill is insistent they're works of visual art, right down to the logos on the letterheads. On the one level, they're funny, like a comedian working out their routine. But if you read the actual text, it's about a failed communication: "I know tomorrow is your day off but we just have to catch up on these memos. . . ."

It's the poetry of everyday speech. I always think of Wegman as being in the same group as Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers. It's really about the weirdness of normalcy and the weirdness of conventions. I mean, it's the freewheeling 1970s and here's Wegman writing about looking for an ironing class . . .

Will Fenstermaker: At the Parks and Recreation department.

Doug Eklund: . . . which is just so far removed from Chris Burden crawling across broken glass or that kind of thing. That, to me, is the space that Wegman carved out for himself. That's his persona.

On June 3, I'm introducing a talk with Wegman and Allen Ruppersberg, and I'm going to show some fifties comedy routines, like Bob and Ray—which I don't know if you've ever seen but you should. They're a predecessor to Saturday Night Live. There's a clear line from these great comedians like Lenny Bruce, who were the counterculture of their day, with their use of nonsense and absurdity, into these artists here.

Humor—I mean, in New York, there's nothing worse than a sense of humor.

Will Fenstermaker: Well, we're all making Very Serious Art over here, Doug.

Doug Eklund: Yeah, yeah. And to the people in Los Angeles, it was just like, come on! Lighten up.

William Wegman (American, born 1943). Man Ray, Do You Want To . . . (still), 1972. Single-channel digital video, transferred from Sony AV 3600 1/2-inch video tape, black-and-white, sound, 1 min., 55 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Wegman and Christine Burgin, 2017 (2017.210.68). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Will Fenstermaker: Is that levity a product of the culture? Los Angeles is, or maybe was, so dominated by Hollywood and the entertainment industry. Angelenos are savvy consumers of media. Or maybe it's all that sun and nice weather?

Doug Eklund: Better pot! No, I kid. That's the view from the East Coast: LA is the most anti-art place imaginable. But these artists, who were bowing out of the New York careerism, were making art that reflected that situation of self-consciousness and self-awareness.

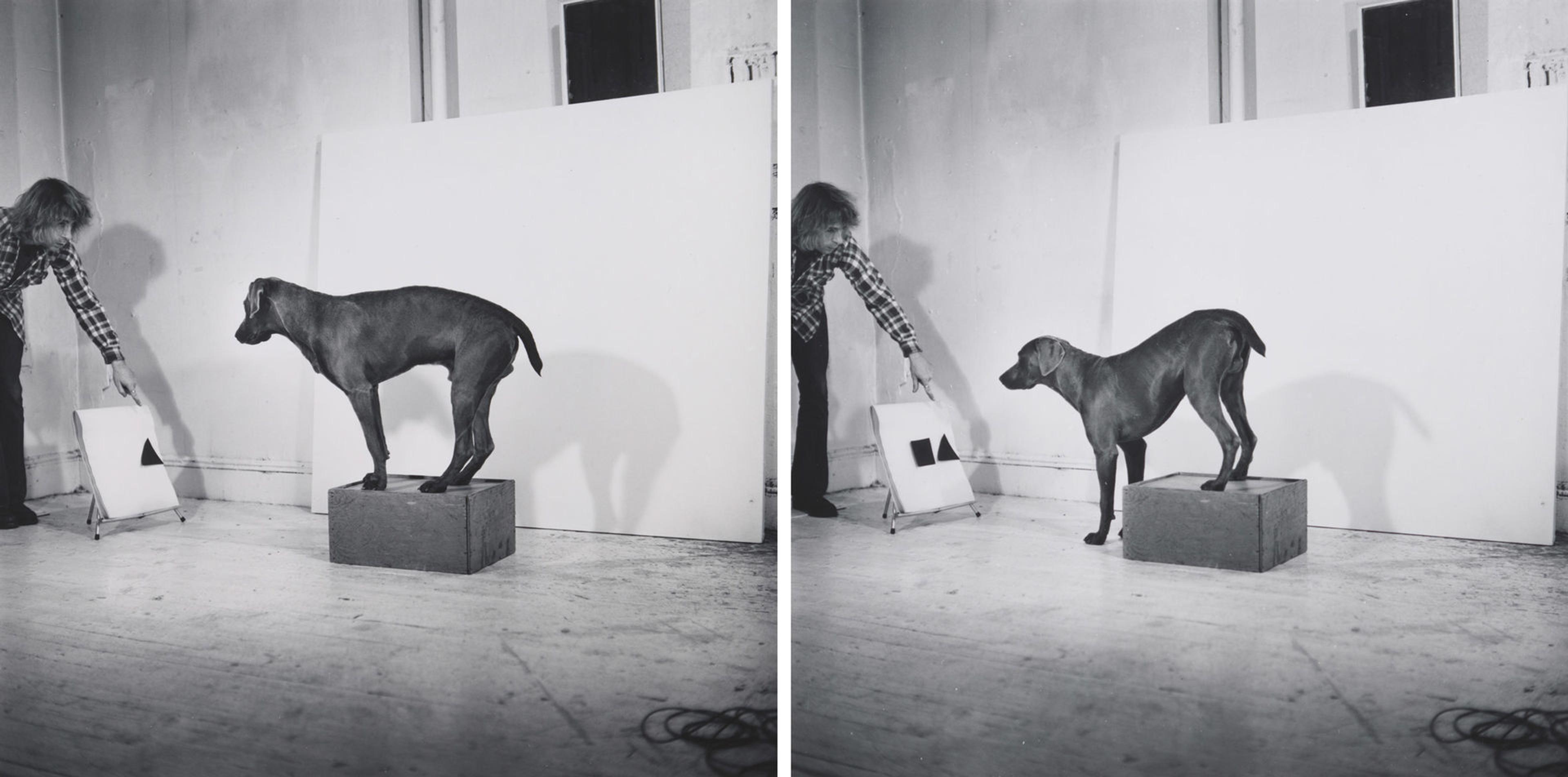

Will Fenstermaker: Would it be fair to say that Wegman's dog in some way stands for the perception the East Coast had of the West Coast—as this naïf?

Doug Eklund: Sure, although I don't know if it was worked out that way. You could say using a dog in your work is the lowest form of comedic pandering, but it's also a completely brilliant way of establishing a communication with the viewer, by centering the idea around this canine engagement and the dog's total cluelessness regarding what's going on.

Will Fenstermaker: But he's also completely genuine, too. Because it's his dog! And Wegman loves his dogs.

William Wegman (American, born 1943). The Kiss (still), 1972. Single-channel digital video, transferred from Sony AV 3600 1/2-inch video tape, black-and-white, sound, 1 min., 27 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of William Wegman and Christine Burgin, 2017 (2017.210.55). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Doug Eklund: Absolutely. There's a video in the sequence called Treat Bottle where the dog is pushing a glass bottle filled with dog treats. It's all about real frustration, real things you can relate to, but three quarters of the way through, the bottle breaks and he's pushing around the broken glass. I thought, "Oh my god, I'm gonna get protestors in here!" I have to explain to people, Man Ray was more loved and coddled than any human we probably know.

Will Fenstermaker: Right, no animals were harmed. . . . That's the other thing that's compelling about Wegman's humor. It's never cruel, which is something we New Yorkers are often guilty of being. His humor is never at somebody's expense. He has a subject, maybe, but never a target.

Doug Eklund: No, never cruel. The closest thing to a target might be the way the dog kind of stands in for the viewer. The seventies were a moment of reduction in Conceptual art, where the artist's body becomes the subject, object, and referent all in one. Substituting the dog is kind of poking at that. I mean, think of Sol LeWitt or someone like that. I get his work, I like it, I appreciate it, but if you asked me to work out the permutations, well, I have no f---ing idea! And so the dog is about the viewer following along, trying to keep up.

When you see the videos with the dog, there's just something about them. They have a special kind of coherence. It's like when Baldessari had his Post Studio class, where he taught that the medium is not the point of the artwork. The point for Wegman was to pursue an image that could be produced in the mind of a viewer, across media.

William Wegman (American, born 1943). Before/On/After: Permutations I (details), 1972. Gelatin silver prints, each 10 3/8 x 10 1/2 in. (26.4 x 26.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2016 (2016.598a–g). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Will Fenstermaker: Sure, and then so much of the meaning then kind of lives between the images, or somewhere else entirely. One thing that's so great about Before/On/After, the work from which the exhibition gets its title, is that when you see it on the website or the signs around the Museum, it doesn't really work because you're just seeing one image out of a series of seven.

Doug Eklund: No, you don't really get it.

Will Fenstermaker: It totally fails, and I love that. It's only once you see it serialized that it takes on meaning because you can make sense of the joke. You understand the iconography, how each little shape denotes an action that Man Ray is obediently performing—but which is probably staged to begin with. He makes the rules of his little game apparent in a way that an artist like Sol LeWitt does not, and I think that's really humanizing.

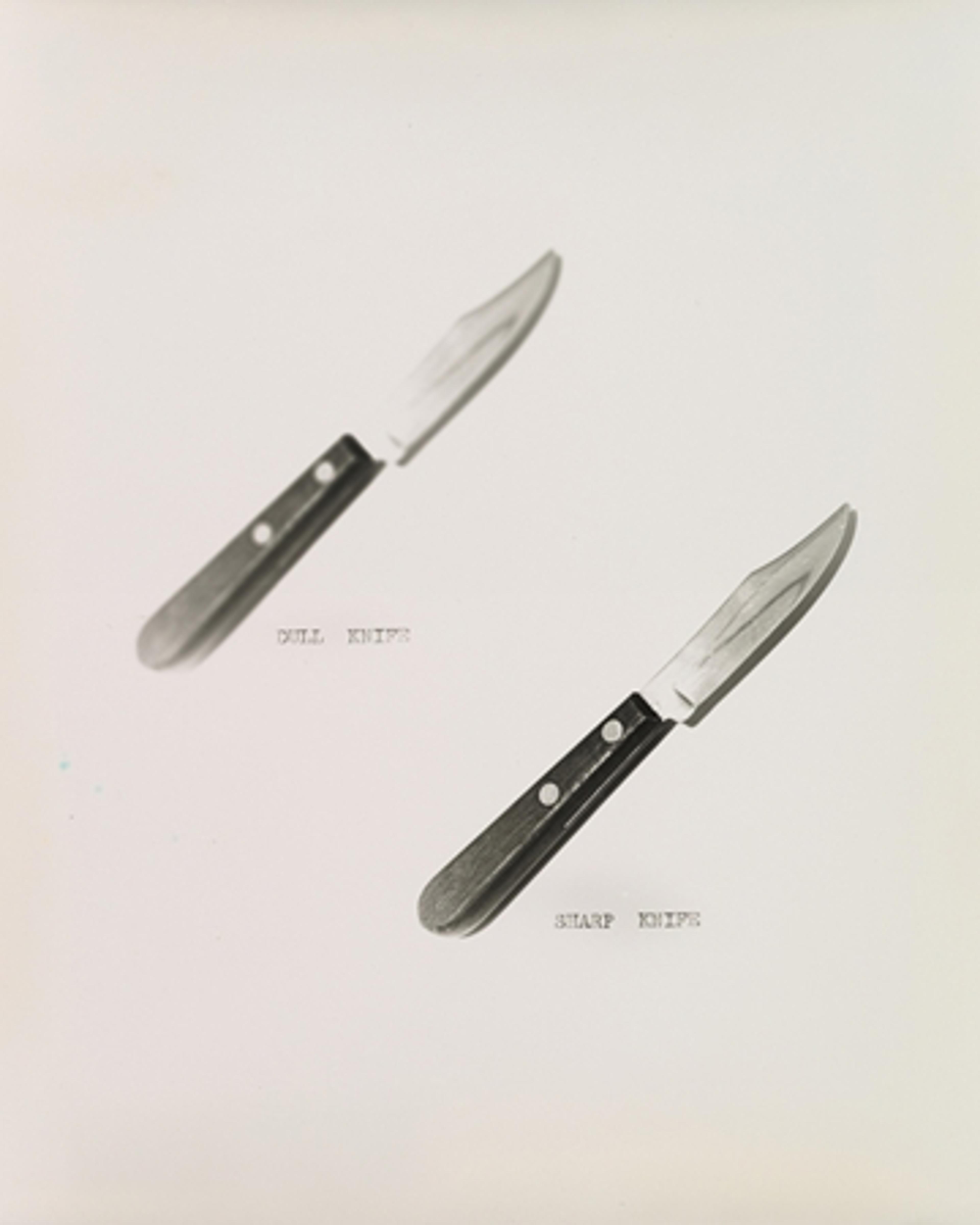

Doug Eklund: Exactly. The meaning is always in between. It's a beautiful single image, but it doesn't actually communicate anything about the work itself. That said, even though Wegman doesn't come from that strict photo world, he was very interested in photographic conventions, like this idea of a self-contained image. All of those conventions are in works like Dull Knife/Sharp Knife, but it's not this rarefied exercise.

Right: William Wegman (American, born 1943). Dull Knife/Sharp Knife, 1972. Gelatin silver print, 12 3/8 x 10 13/16 in. (31.5 x 27.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 2011 (2011.314). © William Wegman, Courtesy of the Artist

Will Fenstermaker: You mentioned Robert Cumming as one of the lesser-known artists in the exhibition. I'd never seen his work before his survey The Secret Life of Objects at the Eastman Museum last year. One of the reasons he's interesting here is that he comes from that classic photo world, but was also working with a lot of ideas that got picked up years later.

Doug Eklund: Yeah, he was a real idea generator who came from the traditional photo world, where things get much wonkier and nerdier and less interesting to me. When I found these pictures, I just fell in love. I'm also a movie nut, and these represent the last moment of so many things in terms of the history of film and the changing ways of making films.

Will Fenstermaker: He was working years before the Pictures Generation, for example, but was dealing with these same ideas about artifice and context that became vogue in the eighties.

Doug Eklund: Cumming's idea of staging, of constructing something for the camera, was really radical at the time. At this point in his career, Cumming was searching out readymade examples of the Rube Goldberg contraptions he used to build and photograph in his studio.

Will Fenstermaker: Totally. He had a real Fischli/Weiss thing going on for a while.

Doug Eklund: Curators have different things that get them excited. For me, the greatest part of the job is to be able to find things that no one else is looking at. It's always a little different, but it always comes from somewhere else. That's how art is, you know? It's all just fragments that people pick up and tie into different arrangements to make new work.

Notes

[1] Douglas Eklund, "'No Success Like Failure': Deskilling and Collaboration in the Work of John Baldessari," in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty (Los Angeles and New York: LACMA / Prestel, 2009), 79–86.

This interview has been edited for publication.

Related Content

Before/On/After: William Wegman and California Conceptualism is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 15, 2018.

Listen to William Wegman discuss Walker Evans's postcard collection in The Artist Project.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Conceptual Art and Photography" and "Art and Photography: The 1980s"

Read more Curator Conversations.

Will Fenstermaker

Will Fenstermaker is an editor and producer in the Digital Department at The Met.