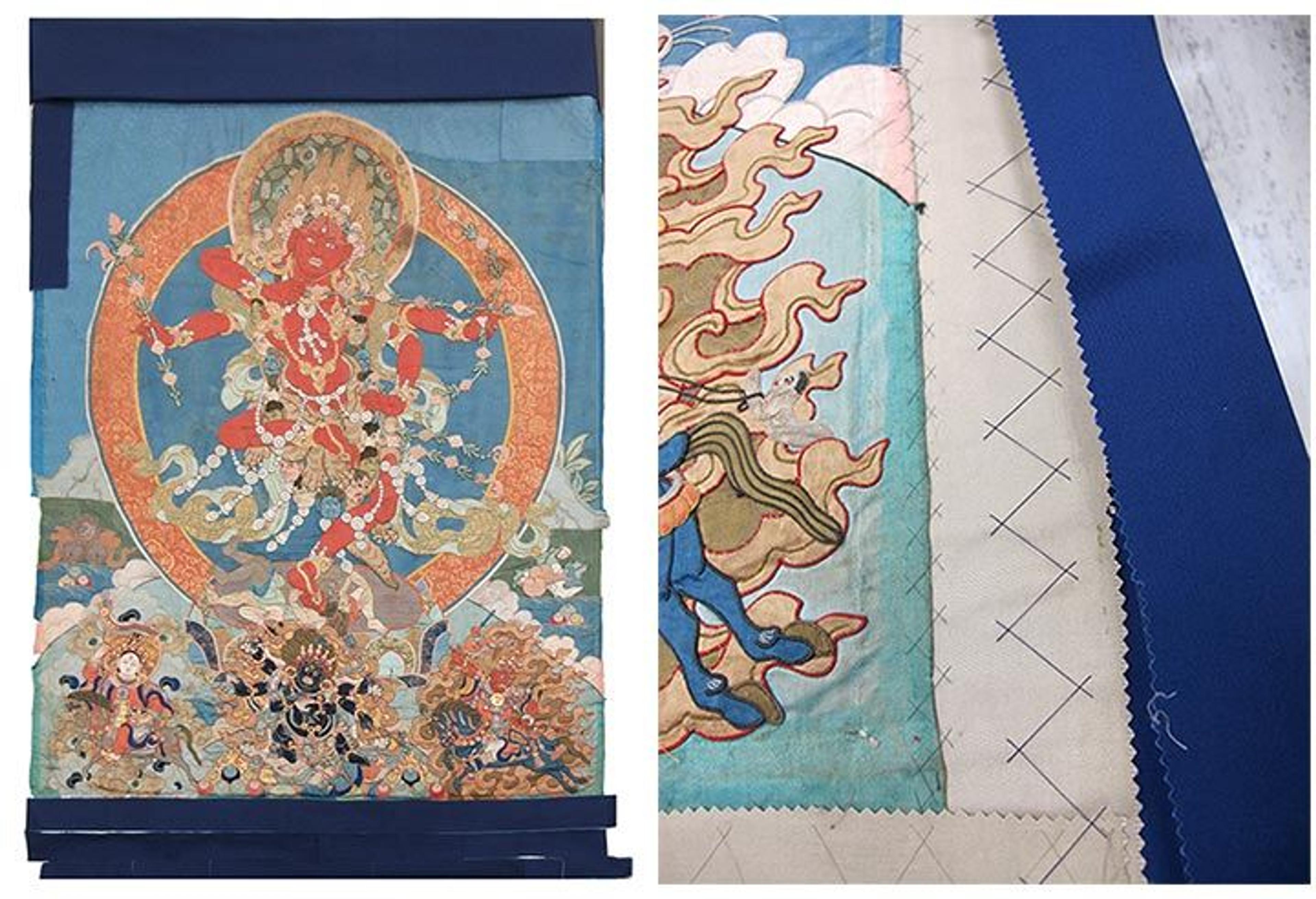

The Goddess Kurukulla, 19th century. Tibet. Appliquéd satin, brocade, and damask, embroidered silk, and painted details, 56 x 47 in. (142.2 x 119.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Zimmerman Family Collection, 2014 (2014.720.1). Left: recto (front side); Right: verso (back side)

The Goddess Kurukulla, a beautifully constructed appliquéd thangka in The Met collection, is a fine example of the work of the skilled Tibetan artists who create this highly regarded type of thangka. Appliquéd and embroidered thangkas may be less well known in the West than the painted ones, but they are considered more precious and are highly valued in Tibetan culture. Although earlier examples of appliquéd thangkas are extant in museum collections, this is a wonderful example that dates to the 19th century.

I recently attended a thangka conservation workshop taught by Tibetan specialist and conservator Ann Shaftel, where I learned that thangkas, which provide a tangible focus for worship and ritual, have historically been revered as portable religious icons. Traditionally, the images are stored rolled and are unrolled on a regular basis to hang vertically. Over time this can damage the fabric, paint, and other media used, making thangkas a challenge to conserve.

While most thangkas are poster size, others can be as tall as a nine- to ten-story building. These large examples, which are used for public viewings, are typically the appliquéd type, because they must be rolled, folded, and carried up mountains by teams of religious priests and practitioners. The highly esteemed tradition of creating appliquéd thangkas is a skill of such great value that the Dalai Lamas have a master tailor designated for this task.

Materials and Techniques

To learn more about the Kurukulla thangka, conservators in the Department of Textile Conservation examined its condition, materials, and construction with a high-powered microscope.

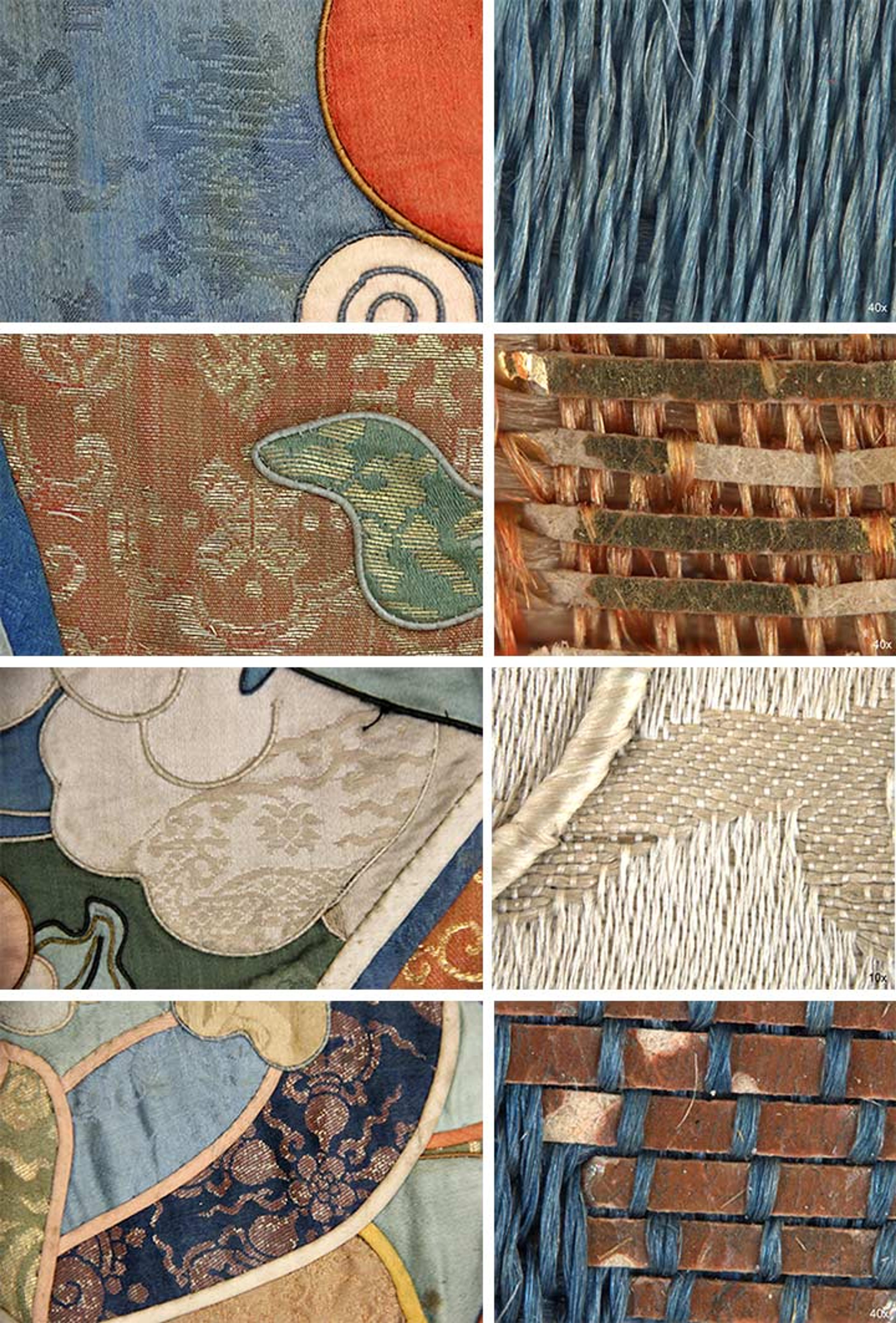

Left: Examples of textile fragments in various weave structures. Right: Special high-magnification photographs, or micrographs, using extended focus Z-stacking, 10x–40x

We discovered that the thangka is composed of a variety of textiles possibly spanning almost the entire Ching dynasty (1644–1912). There are many examples of classic textile designs and weave structures, dyed with both natural and synthetic dyes, laid side-by-side. Numerous patterned-silk fabrics comprising satin weaves, damask weaves, and brocades in compound weaves, with supplementary wefts of gold and silver metal thread as well as polychrome silk thread, have been artistically positioned to depict an action-packed and colorful scene.

Upper left: Design outlined by silk thread wrapped around a core of horsehair. Upper right: Micrograph using extended focus Z-stacking, 20x. Lower left: Hand painting on textile. Lower right: Embroidery technique, couching, 10x

The skillful artisans utilize embroidery techniques to shape and define the figures. In particular, they use polychrome silk thread, wrapped around a core of horsehair (top row) and "couched" onto the textile (bottom right), to outline the designs and create a dimensional effect. In addition, they draw hand-painted accents onto the fabric pieces (bottom left).

Conservation

After carefully examining the thangka and discussing it with the curator, we identified two main issues that needed to be resolved. Both issues stemmed from the way the thangka had been conserved and displayed before it came to The Met.

A large patch of patterned blue-silk damask had been inserted in the blue background fabric around the figure to replace an area of loss. We determined that the restoration patch was discoloring and stiffening due to the heat-set adhesive sheet that lined it, and we wanted to find a better solution. We also observed that adhesive-backed fabric had been used to restore the lining and borders of the frame, and we wanted to prevent the potential damage of discoloration and transfer of adhesive from this fabric as well.

The restoration patch with the manufacturer's mark in the selvedge

When we removed the adhesive-backed lining and border fabric, the edges of the blue-damask restoration patch were revealed. We found a manufacturer's mark in the selvedge ("Sin Chon H.K.") that showed that this was not a historic textile original to the thangka, but a textile from a Hong Kong manufacturer.

A new and adhesive-free textile fabric was now needed to replace the patch. However, since the original blue background fabric was stained and discolored from years of display, we realized that the best solution would be to custom-dye the new fabric to blend with the original color.

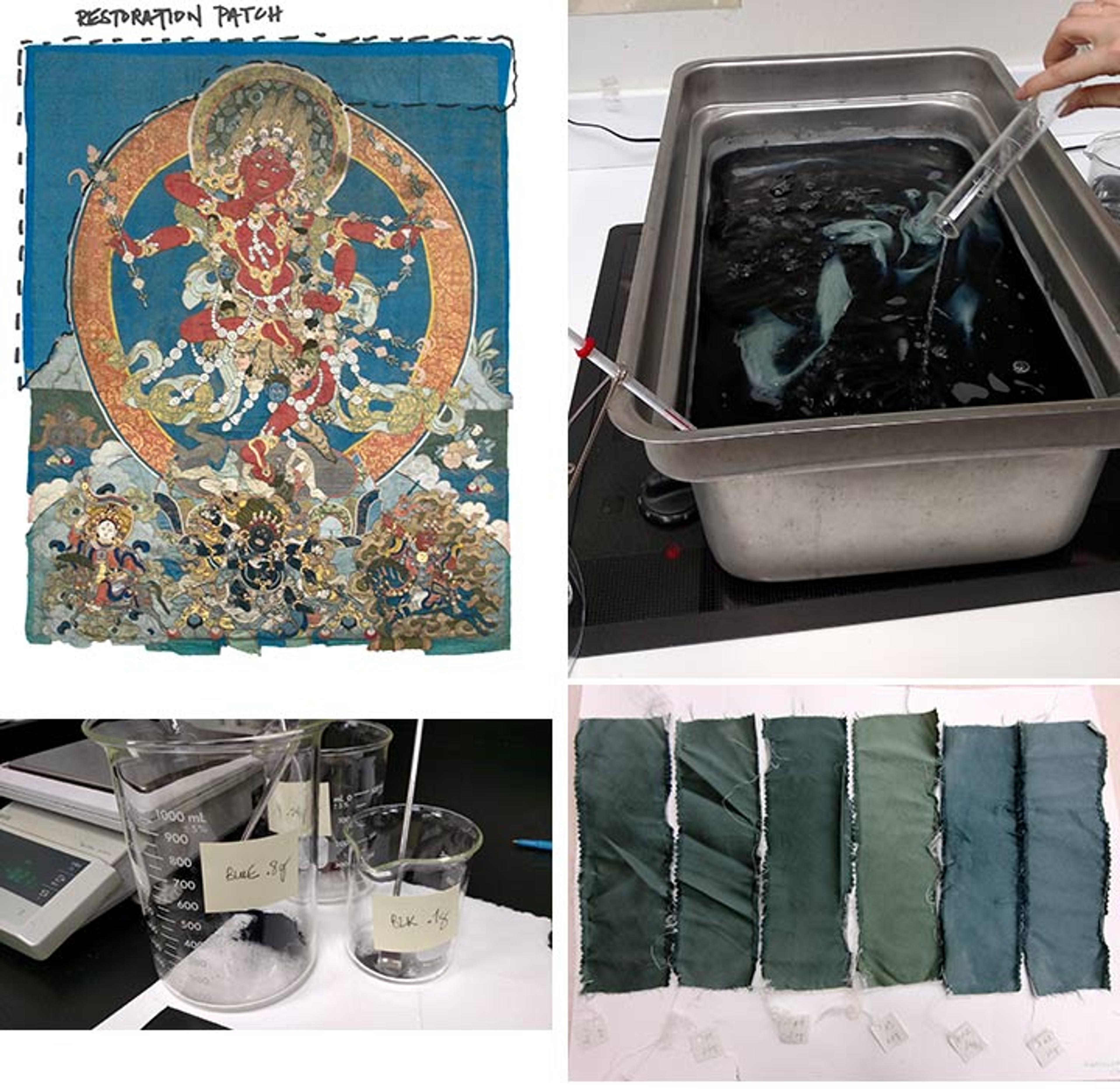

Upper left: The thangka showing the restoration patch that we removed. Upper right: Dye bath. Lower left: Measuring dye stuff. Lower right: Sample swatches of various tones to find the best match

The first step was to determine the weave structure, thread count, density, and best match for the overall color base of the original blue fabric. Creating a dye recipe was a huge challenge, since the replacement fabric spanned the entire top portion of the thangka and down one side, and unfortunately the stains and discoloration also varied from area to area. After a number of dye experiments, we succeeded in creating a mottled, bluish-yellow replacement fabric with brownish undertones that would be an inconspicuous and therefore successful overall match.

Left: Determining the proportions of the new blue borders. Right: Support fabric showing conservation stitching

We also removed the lining and border fabric, which was also a later addition or repair, because of the potential damage that might be caused by off-gassing of its adhesive backing. We then added new, dark-blue cotton fabric borders as a frame (above), in keeping with a more traditional display of the thangka.

The Goddess Kurukulla in the galleries

The numerous discoveries we made from our close examination and analysis of The Goddess Kurukulla revealed the great beauty of the materials that were used—from precious metal and silk threads to organic horsehair—as well as the artistic and skilled handiwork of the master tailor who created it. As conservators at The Met, we are fortunate to research, study, and conserve complex textiles like these, from their expert embroidery stitches to the overall construction that depicts the goddess. We are glad that we can share with museum audiences this up-close view.