Audio Guide

Manet/Degas

Hear how each artist responded to changing aesthetic and political mores, capturing new visions of modern life in nineteenth-century Paris.

1. An Enigmatic Relationship

Hear about the origins of Manet and Degas’s relationship

NARRATOR:

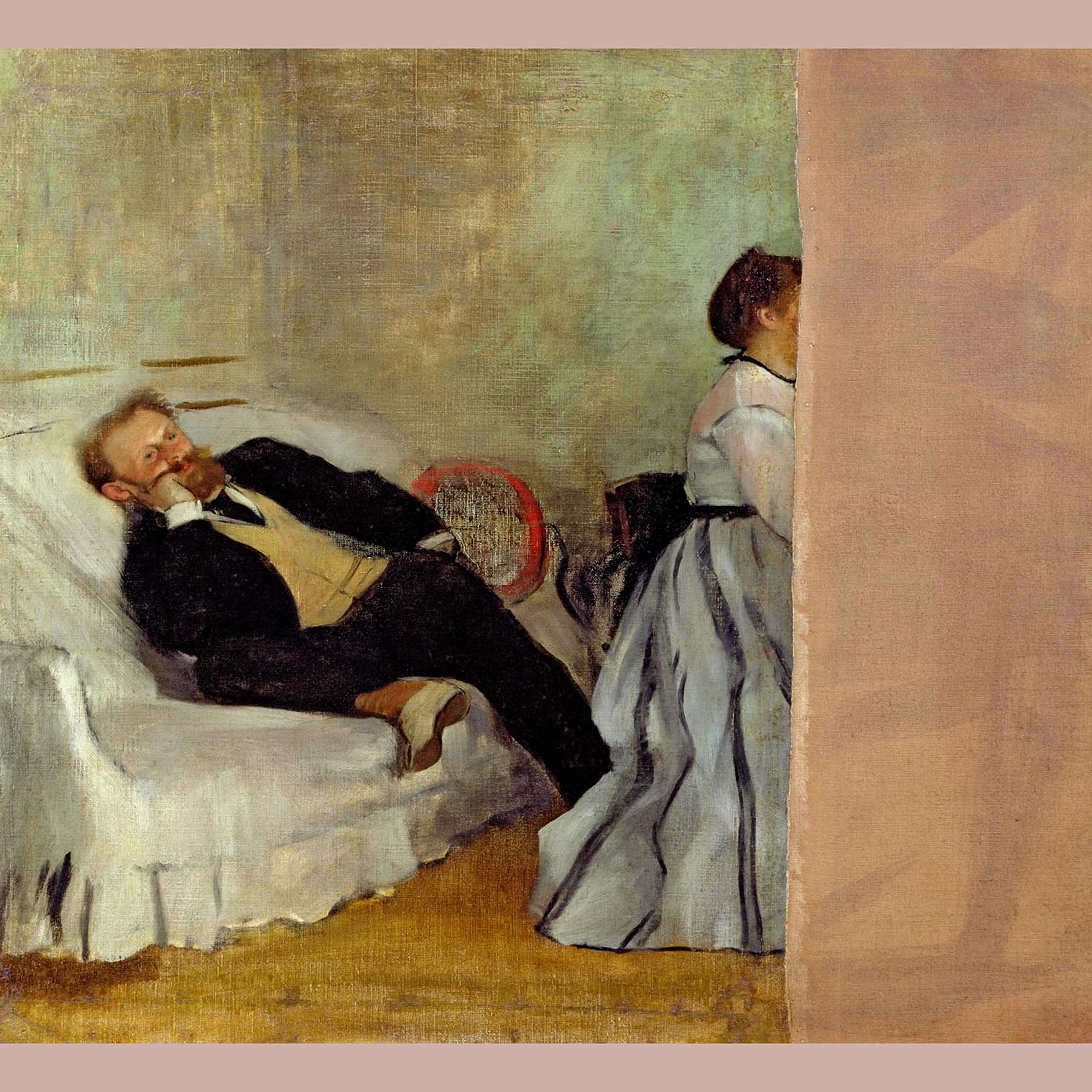

It was an evening like many others. Suzanne Manet played the piano while her husband Édouard reclined on the sofa, lost in reverie. But this particular evening would be immortalized by their friend Edgar Degas, who, with his talent for total recall, would go home and paint the scene as a gift for the young couple.

What happened next has confounded historians for the last 150 years.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Degas later recounts getting to the apartment and seeing the right part of the painting quite violently slashed in a clear cut that cropped the face of Mrs. Manet off.

NARRATOR:

What precipitated this abrupt shift in Manet and Degas’s relationship? Perhaps we can find a clue in their first meeting, less than a decade before, in the galleries of the Louvre.

Manet was thirty-two, Degas thirty. Both, rebellious sons of bourgeois families. And they were among the first generations of artists to avail themselves of a comparatively recent invention—the museum. For artists who had previously studied black-and-white reproductions, the experience of seeing the actual works was a revelation. Here’s Stephan Wolohojian, John Pope-Hennessy Curator of European Paintings, and Ashley Dunn, Associate Curator of Drawings and Prints. They’re co-curators of the exhibition Manet/Degas.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

They could see history in color. The Louvre became a training ground that could in many ways even substitute for the traditional classroom experiences of the Academy.

ASHLEY DUNN:

Degas was standing in the Louvre in front of a painting attributed at the time to Velázquez of the Infanta Margarita Teresa. So, he’s holding a copper plate that would have been covered in a waxy kind of ground and using a needle to draw into that wax, thereby revealing the metal underneath. It was unusual to make an etching outside of the studio. And Manet made a remark along the lines of, “How bold of you to etch directly in front of the motif without any kind of preparatory drawing!”

NARRATOR:

That very etching is featured later in the exhibition alongside one by Manet, after the same painting. We don’t know exactly when Manet made his etching. And whether it was before or after Degas made his colors how we might imagine their exchange.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Manet had already made some pretty major steps on the artistic front when this meeting occurred. Degas was slower to come into being as an artist. So, it’s an interesting moment to imagine a senior artistic figure looking over the shoulder of this more junior one, even though they were contemporaries and in contemporaneous ways exploring the world around them.

NARRATOR:

Manet and Degas would continue to push each other to take the risks that would define their careers. But they left little evidence of their relationship in their papers. For example, though Degas speaks of Manet in his many letters to others, none of his letters is addressed to Manet. And for his part, Manet left just a few letters to Degas.

ASHLEY DUNN:

One of the visual testaments of their relationship, though, is this wonderful series of drawn portraits that Degas made of Manet. He made around ten drawings of him. That is in stark contrast to the fact that we have no clear representations of Degas by Manet. There’s the possibility that he appears in the corner of a racing picture from behind, but we cannot be certain.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

I’m glad you mentioned that, because there may not be letters, but there is a paper trail, literally, and a very moving and rather extraordinary series of drawings that capture Manet in different moments, in different frames of mind, truly evocative of the kind of familiarity that just doesn’t come with casual observation.

NARRATOR:

Like Degas’s painting of Manet lost in reverie—the painting that Manet so violently slashed. Scholars and others have speculated that Manet was dissatisfied with the way that Degas painted the profile of Suzanne and that he may have painted his own portrait of her as a corrective.

ASHLEY DUNN:

In an early red chalk drawing of Suzanne the profile is repeated very insistently. It gives you the sense that there was maybe a degree of obsession about getting that profile right.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Outraged that his friend would have defaced—literally—his painting that way, Degas apparently grabbed it and took it back.

How many of us have had a moment in a friendship or in any relationship where you just sit back, and you say this is it? This is the great moment, just the way that evening must have been, and how often those moments are fractured or broken and are completely irreparable. They can’t be mended together, or if they can, they’re always mended and never whole.

NARRATOR:

Keep listening as we explore Manet and Degas’s enigmatic relationship, through an unprecedented exploration of the artists’ work, exhibited side by side.

This audio feature is sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies, produced in collaboration with Acoustiguide.

- 1. An Enigmatic Relationship

- 2. Shocking Subjects and Modern Paris

- 3. The Social World of Manet and Degas

- 4. Degas in New Orleans

- 5. Degas's Collection of Manet