Now on View: Works by Vittore Carpaccio, Master Draftsman of Renaissance Italy

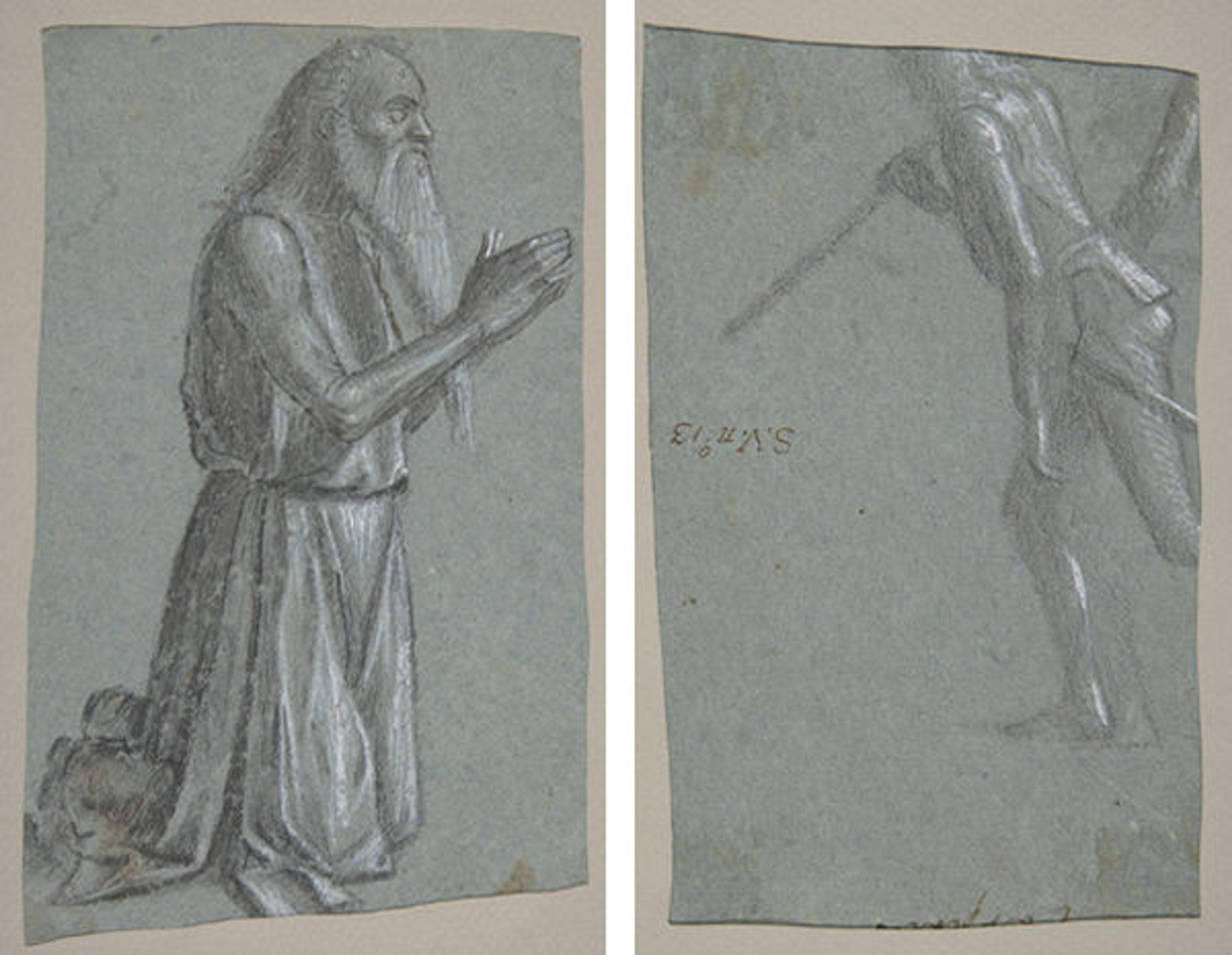

Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1460/66?–1525/26). Study for a Kneeling St. Jerome (recto); Study of Soldier with a Spear (verso), ca. 1493. Brush with black ink and gray wash, over traces of black chalk or charcoal, highlighted with white gouache on blue paper (recto); black chalk, highlighted with white gouache, with some brush and gray wash (verso); 6 3/4 x 4 1/8 in. (17.2 x 10.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Fletcher and Rogers Funds, 1998 (1998.14a, b)

«Well known for the outstanding storytelling of his cycles of paintings, the Renaissance artist Vittore Carpaccio (1460/66?–1525/26) was also a prolific draftsman. Four of the artist's drawings are part of the Met's collection and currently on view in the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery.»

Unlike most of his Venetian contemporaries, Carpaccio adopted drawing as one of his primary forms of expression when creating a work of art. As can be seen in the selection of works on display, Carpaccio used the medium of drawing for a variety of purposes: to sketch and develop ideas for compositions, to study the human figure from the living model, to design costumes, to prepare the final compositions in the full scale of a cartoon, and to record successful figures and designs for reuse by the workshop. Furthermore, Carpaccio was among the first to adopt blue paper as a preferred support for his drawings.

Chronologically, the first sheet of drawings in the Museum's collection appears to have been preparatory studies for one of Carpaccio's earliest commissions—the monumental altarpiece in the Cathedral of Zadar in current-day Croatia (at the time a province of the Republic of Venice), a project the artist undertook around 1493. The study of an old man kneeling to the right was likely meant for the figure of Saint Jerome. The artist also used the other side of the sheet for a study of a boy seen from the rear, holding a stick, which was probably conceived for the figure of a soldier with a spear that was not included in the final composition. The sheet was most likely kept in the artist's workshop for reuse in future commissions, and later became part of the so-called Sagredo-Borghese album assembled in Venice during the eighteenth century, but has since been unbound and dispersed.

Attributed to Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1460/66?–1525/26). Study for Saint Martin and the Beggar, 1493. Pen and gray ink, brush and gray wash, over faint traces of black chalk; 7 x 4 1/2 in. (17.8 x 11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Charles and Jessie Price Gift, 2002 (2002.93)

In the preparatory drawing for Saint Martin and the Beggar (a scene also featured on the Zadar altarpiece), Carpaccio needs little more than the trace of an outline in pen and ink to depict the young saint on horseback, cutting a piece from his cloak to clothe the beggar standing by his side. The Saint Jerome and Saint Martin works are both executed on blue paper, a support which emphasized the chromatic quality of the compositions and was greatly popularized by Carpaccio.

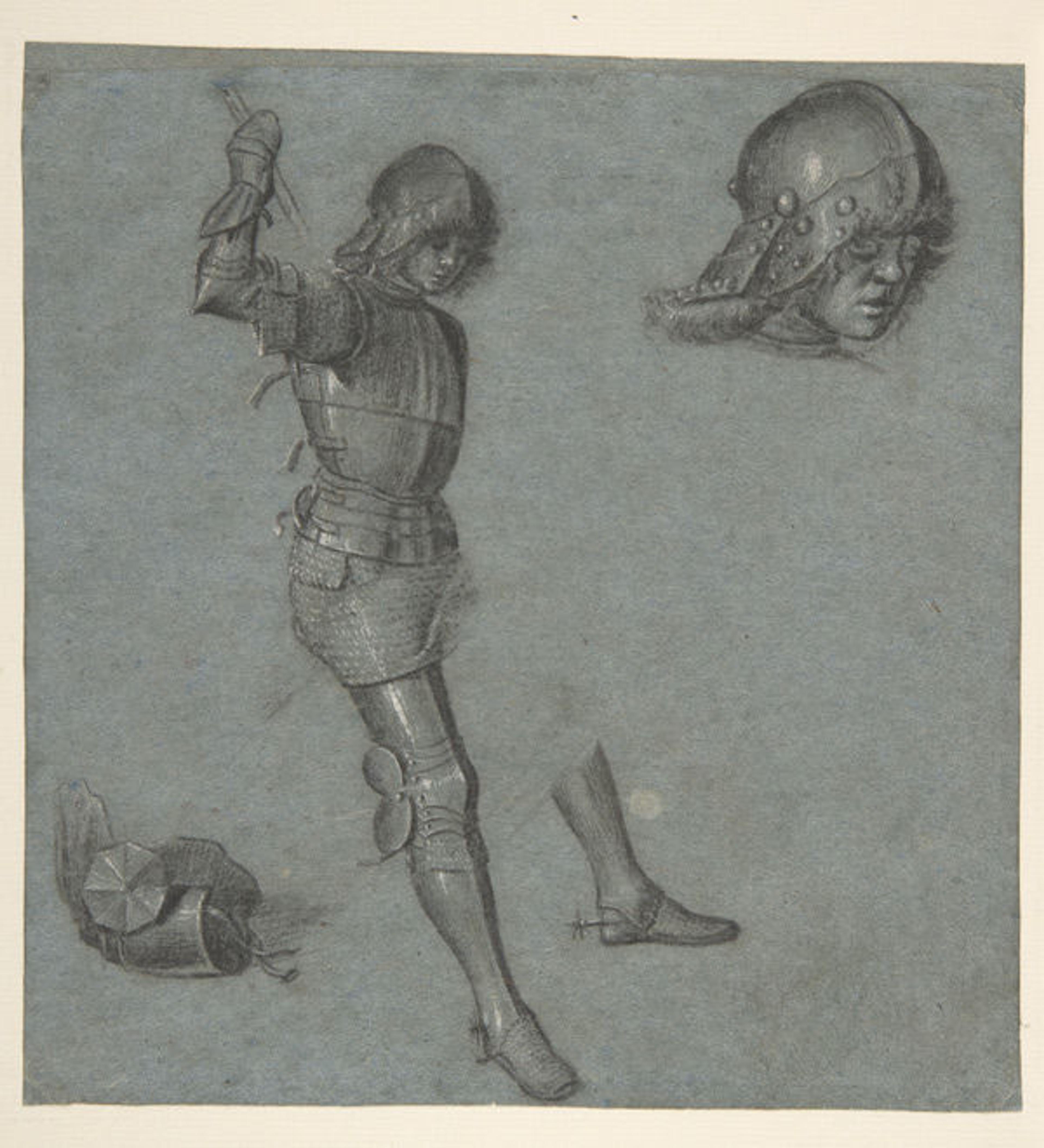

Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1460/66?–1525/26). Studies of a Seated Youth in Armor, ca. 1505. Point of brush with grey wash, highlighted with white gouache on blue paper; 7 1/2 x 7 1/16 in. (19.0 x 18.0 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1954 (54.119)

Most likely drawn from life, the celebrated drawing of a young model dressed in armor was intended as a preparatory study for the soldier Saint George fighting the dragon. The main figure is supplemented by another study of a helmet in the upper right and by a detail of the armor in the lower left. Carpaccio chose to draw these two elements on a larger scale to explore in greater detail the chiseled decoration of the armor. Carpaccio achieved a great sense of depth by using the chromatic contrast of the blue paper in combination with the highlights in white gouache and dark shadows, made by a few parallel lines. The purpose of the drawing is unknown, as the figure of the saint was represented differently in the well-known cycle dedicated to the life of Saint George, which Carpaccio painted in in Venice around 1502–08.

Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1460/66?–1525/26). Standing Female Figure (St. Anne; Cartoon for a Painting) (left) and detail of the pricked outline of the hands (right), ca. 1500–05. Pen and brown ink, brush and grey-brown wash, over charcoal underdrawing; outlines pricked for transfer, on two glued sheets of paper with overlapping joins; Sheet: 16 1/16 × 8 13/16 in. (40.8 × 22.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Partial and promised gift of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Tobey in honor of George R. Goldner, 2013 (2013.641)

The newly acquired Study for a Standing Female Figure is the only surviving example of a cartoon (full-scale drawing) made by a Renaissance Venetian artist. Carpaccio made the drawing as a study for the female figure seen at the far left of his painting with the Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan). It was originally installed in 1502–04 as part of a decorative cycle dedicated to life of the Virgin for the Venetian Scuola degli Albanesi. To transfer his design from the sheet onto the canvas, Carpaccio finely pricked the contours of the drawing with a needle before pouncing the holes with charcoal dust; as a result of this process (known as spolvero), a dotted outline of the design was transferred to the canvas and thus ready to be painted.

Attributed to Antonello da Messina (Antonello di Giovanni d'Antonio) (Italian, ca. 1430–1479). Group of Draped Figures, early 1460s. Tip of the brush (or fine pen?) and brown ink; 4 5/16 x 5 7/8 in. (11 x 14.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.265)

The geometrical and almost abstract qualities of the drapery in the Standing Female Figure, arranged by Carpaccio in a series of sharp and angular folds, are somewhat reminiscent of the example of Antonello da Messina. The artist was in Venice around 1475 and can be listed among Carpaccio's most important references. This becomes clear when we compare Carpaccio's study with Antonello's Group of Draped Women, a rare drawing from the early 1460s. Through the delicate shading, made with the point of a brush, Carpaccio infused a softer pictorial effect to his study.

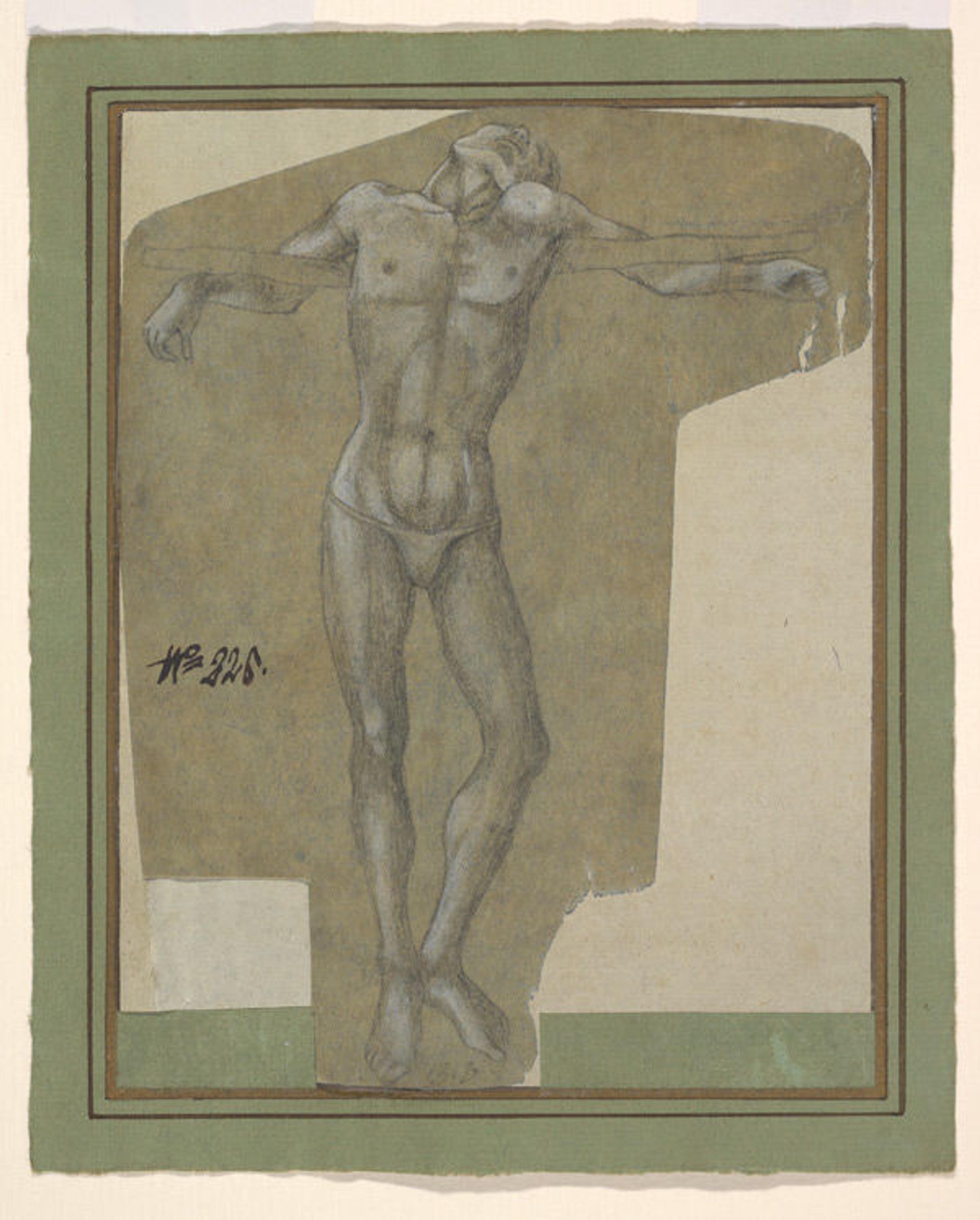

Anonymous (Italian, Ferrarese, 15th century). The Good Thief, ca. 1470–80. Metalpoint, charcoal, heightened with white gouache; Sheet: 7 1/16 x 5 1/2 in. (18 x 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Guy Wildenstein Gift, 2012 (2012.44)

Alongside Carpaccio's autograph drawings, the newly acquired study of The Good Thief is shown in the rotation. The sheet shows a preparatory study for a Crucifixion scene, drawn by an anonymous Venetian or Ferrarese draftsman of the late fifteenth century. Although not made by Carpaccio, its resemblance in style and technique with Carpaccio's draftsmanship, as well as its close relation to the powerful foreshortening of the figures found in Carpaccio's Ten Thousand Martyrs painted in 1515 (now at the Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice), warrant their pairing.

Furio Rinaldi

Furio Rinaldi is a research assistant in the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Carmen Bambach

Curator Carmen C. Bambach is a specialist in Italian Renaissance art. She is the author of Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300–1600 (Cambridge University Press, 1999) and Una eredità difficile: i disegni ed i manoscritti di Leonardo tra mito e documento (Florence, 2009), more than 70 scholarly articles, and 10 exhibition catalogues, including Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer (2017), The Drawings of Bronzino (2010), An Italian Journey (2010), Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman (2003), Correggio and Parmigianino (2000), and The Drawings of Filippino Lippi and His Circle (1997).