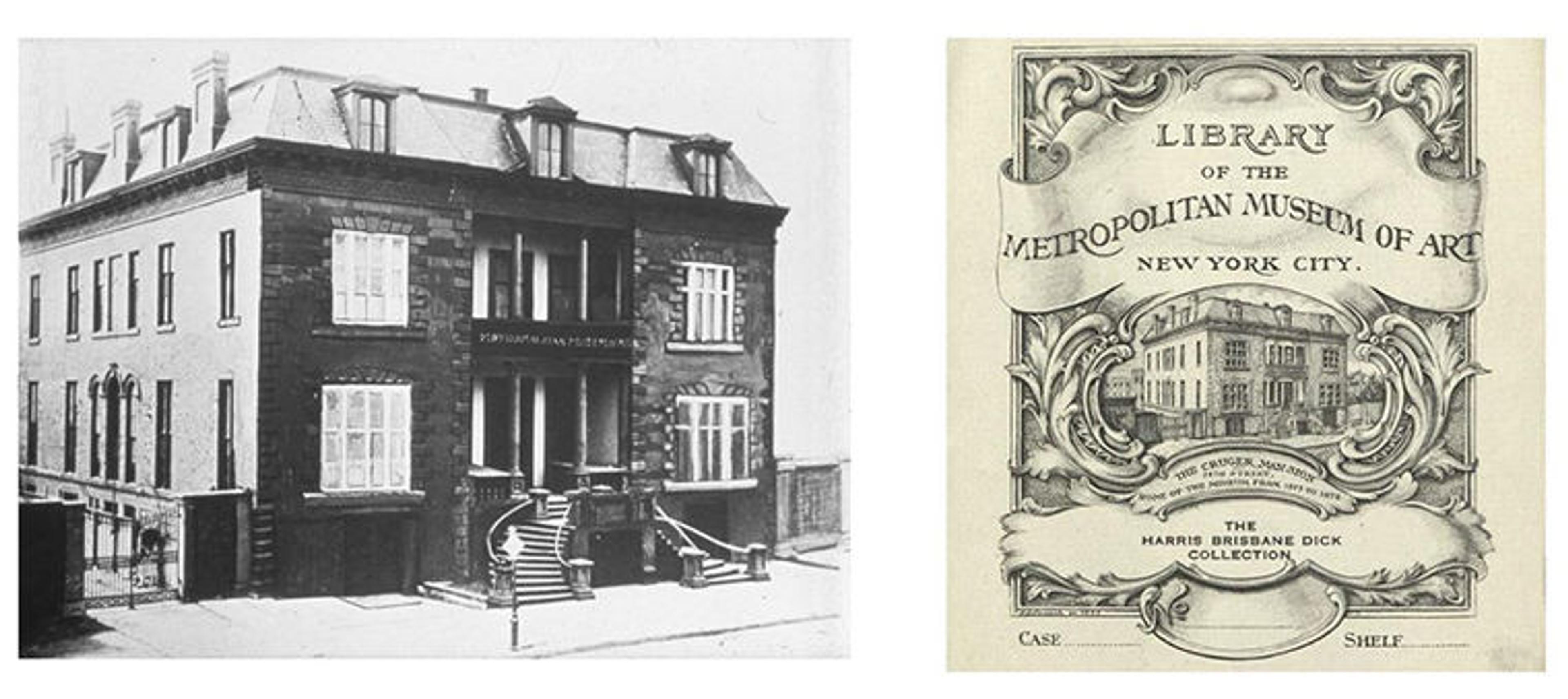

The Douglas Mansion, also known as the Cruger House and the Douglas-Cruger Mansion where The Metropolitan Museum of Art resided between 1873 and 1878. The Mansion is depicted at right in an early library bookplate engraved by Edwin Davis French in 1895.

This is the first of a number of articles on the history of The Met's great library. They are part of our contribution to The Met's 150th anniversary celebration. What follows is the first in the series. It provides the background and a brief history of the first forty years of the library.

The ambitions of the Museum's founders were passionate, unrestrained, and inspired by civic pride and an emerging national identity. William Cullen Bryant persuasively made the case in his address at the inaugural meeting of New York worthies at the Union League Club in 1869, which laid the foundation of the plan. Bryant spoke on the "subject of founding in this city a Museum of Art, a repository of the productions of artists of every class, which shall be in some measure worthy of this great metropolis and of the wide empire in which New York is the commercial center." Another speaker, Professor George Fiske Comfort of Princeton University proclaimed, "In the year 1776 this nation declared her political independence of Europe. The provincial relation was then severed as regards politics; may we not now begin institutions that by the year 1876 shall sever the provincial relation of America to Europe in respect to Art?" This aspiration drew cheers from the assembled crowd of more than three hundred prominent artists, editors, architects, lawyers, merchants, and clergyman.

In 1870, the New York State Legislature granted an act of incorporation for the institution we now refer to as The Met. The new Museum's charter expressed its mission "to be located in the City of New York, for the purpose of encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts, and the application of arts to manufacture and practical life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and, to that end, of furnishing popular instruction." While the dreams and ambitions of the founders of the Museum were seemingly without limit, the first initiatives to create a museum and library were inevitably modest. The library can trace its history to the Douglas Mansion, the site on 228 West 14th Street that served as The Met's second temporary residence. Books, pamphlets, and publications from other museums began to accumulate—the early gatherings of a library that now exceeds one million volumes.

The Met's nomadic existence concluded in 1880 with the opening of its first building in Central Park, designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould. That same year, the Museum made a brilliant hire that was to ensure the successful and accelerated development of the library.

The Met's first building in Central Park facing northwest, showing the south (Central Park) and east (later Fifth Avenue) facades.

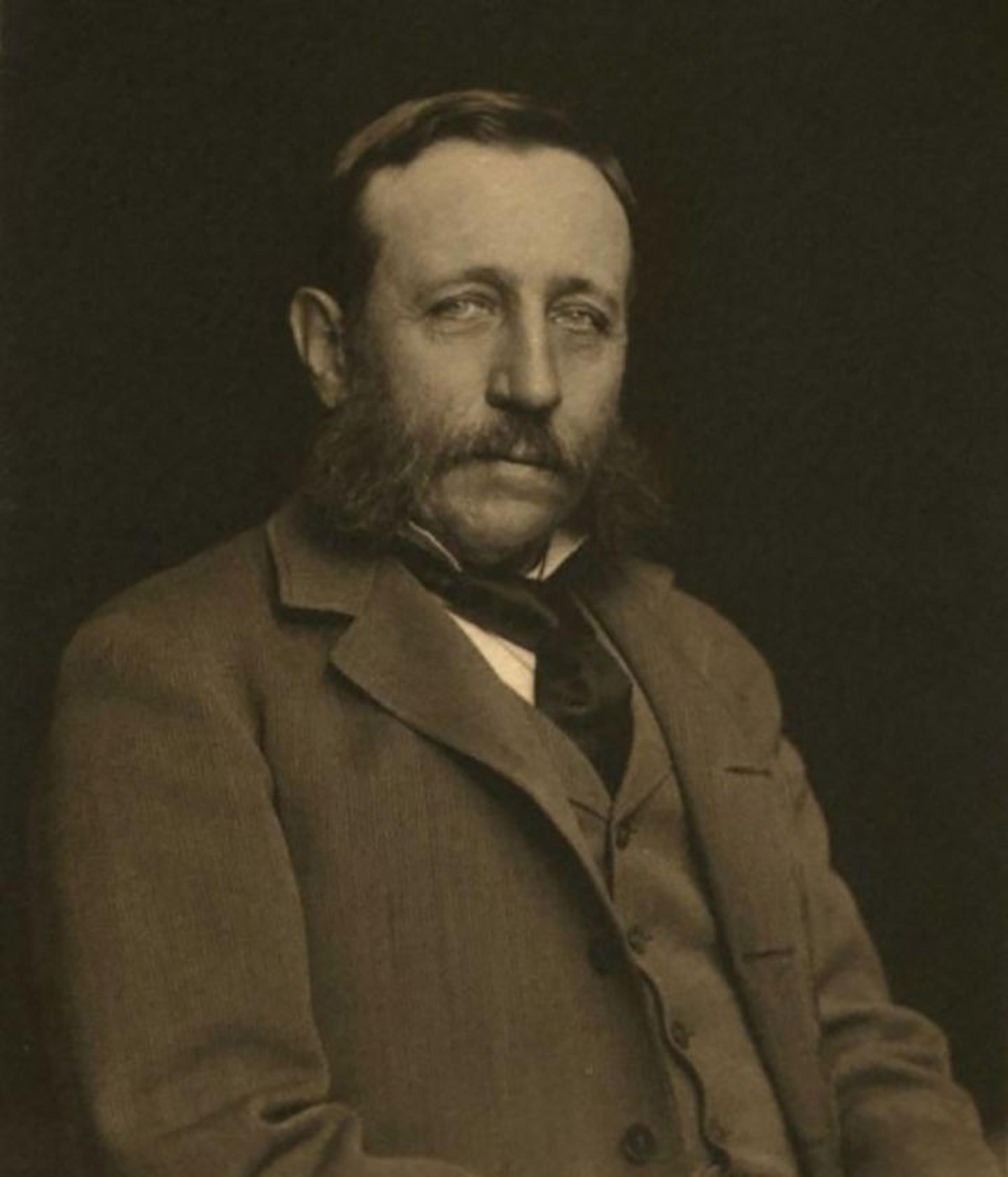

More than a decade before The Met employed a curator for painting, sculpture, and casts, William Loring Andrews was appointed Librarian. Andrews was one of the most distinguished bibliophiles and book collectors of his period. Andrews was also a founder of The Met, a member of the Executive Committee, and an active Trustee during what would be his thirty-nine-year service as Librarian. His title was modified to Honorary Librarian in the 1890 report, not intended as an honorific, but rather reflecting the fact that he received no compensation for his work. In 1884, Andrews also helped found the Grolier Club, the country's preeminent society of bibliophiles.

William Loring Andrews (1837-1920). Photo courtesy of The Grolier Club of New York

In her 1913 history of The Met, which is especially valuable for its chronicling of the first decades of the Museum, Winifred Howe commented on some of the early challenges that the library faced. She observed, "Comparatively few people realized the imperative need of an art library for the well-rounded development of a museum of Art," an observation as true and relevant today as it was one hundred years ago. It is Watson Library's good fortune that Andrews understood the imperative need, and that he had the guiding and compelling vision of building a library that mirrored the scale and scope of the Museum. Andrews was a successful advocate and champion of the library, and he is the key figure in building the strong foundation that helped to ensure the current library's development and sustainability.

In his contribution to the Annual Report of 1881, Andrews demonstrates his persuasive advocacy, "An Art Library for the use of visitors is an essential part of the working plan of the Museum… The increase of the exhibitions and the necessity of books of reference for the use of the Director and his assistants in preparing catalogs, has led to a more systematic attempt to gather a library. This is now a pressing demand." The report establishes precedents that still guide our work: a plea to trustees for their support, an appeal to members who "will probably find in the libraries very many such works, which will be acceptable and valuable for the use of the Museum." Regarding book acquisition funds he observed, "Expenditures of this nature are among the constant necessities of such an institution." Five hundred dollars was appropriated for the first year's support of the library and purchases were added to the increasing number of gifts. This was Andrews's leitmotif of all subsequent reports, and in this regard, once again, nothing has changed since the earliest days.

Andrews described the first library in the 1880 building in a way that evokes the setting of a story by Edgar Allen Poe:

This handful of books and pamphlets was deposited in a small, dark, damp room in the basement of the first building erected by the city for the Museum in Central Park. Not many feet below the floor of this room little streams of water percolated through the crevices of rocks upon which the foundations of the building rested, and naturally, fever and ague lurked about its walls. It was not a healthy environment for either books or human beings, but the best the Museum could at the time supply.

In 1888, the library moved to a more hospitable room on the second floor of the recently built south wing. It could accommodate 10,000 volumes and about a dozen readers. As the pace of collection building picked up, the Board Room was used to accommodate new spatial needs. There was a pressing need for a proper library to accommodate the growing collection, steadily growing staff, and increased number of outside readers.

Our next post will describe the next phase of The Met's aspiration to establish an exceptional library.

With thanks to Holly Phillips and Sophia Alexandrov for their invaluable assistance