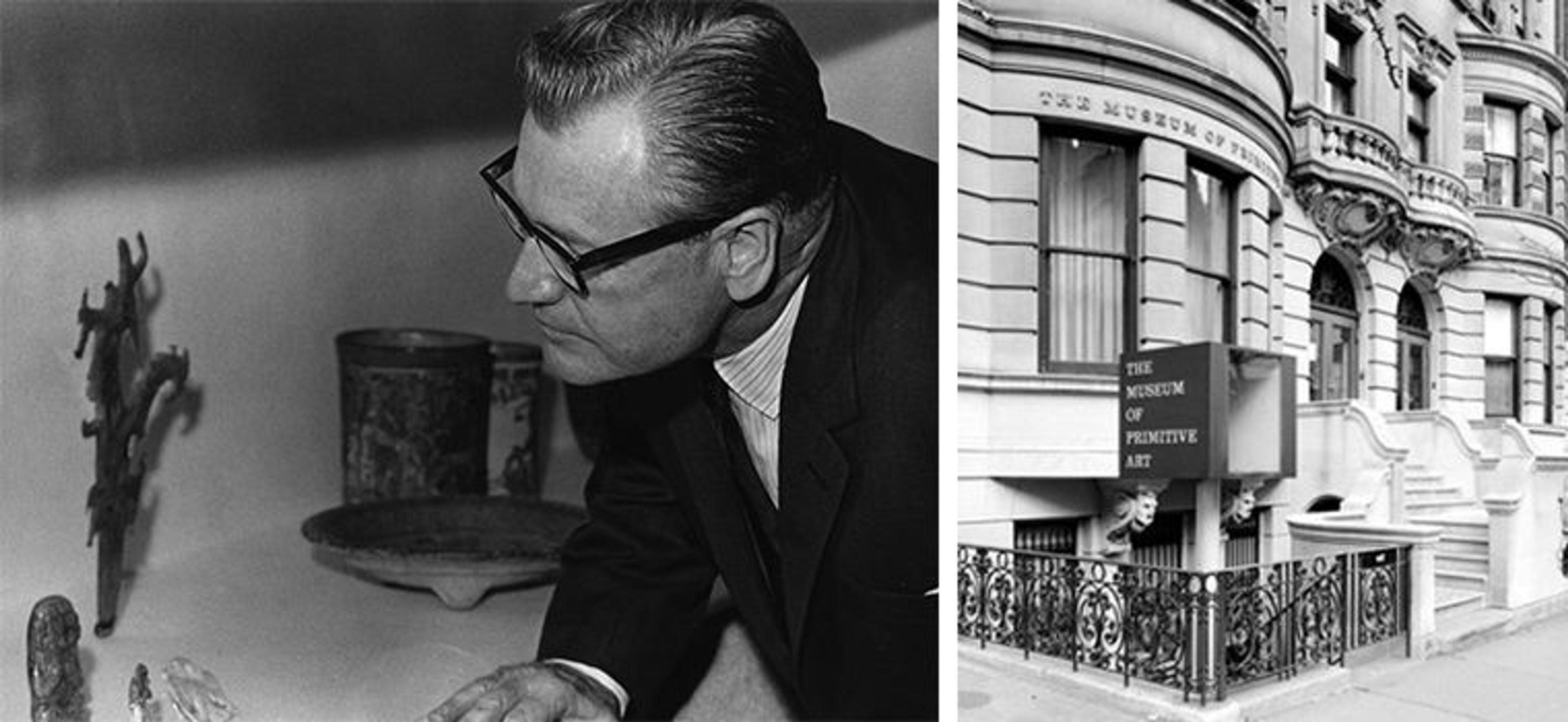

Left: Nelson Rockefeller. Photograph by Michael Fredericks. Right: View of the façade of the Museum of Primitive Art, 15 West 54th Street, New York City. The Museum of Primitive Art Records, The Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (AR.1999.17.98). (Both images from The Nelson A. Rockefeller Vision.)

The next stop on our 150th anniversary tour of the libraries of The Met is The Robert Goldwater Library. Tucked away in a mezzanine level of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, the library is nonetheless one of the Museum's largest departmental libraries, supporting the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. The library documents the indigenous visual arts from these regions, from their beginnings to the present. The library's holdings appear in Watsonline, The Met libraries' online catalogue, and may be requested for use in Watson Library.

Thanks to the depth, breadth, and size of the collection (nearly forty thousand items), its subject specialties, and ever-growing scholarly interest, the library's collection is extensively used by researchers elsewhere in the Museum and by the public.

History

As departmental libraries go, Goldwater Library is a recent invention, not only at The Met but in its prior incarnation. It began its life as the library of the Museum of Primitive Art (MPA). The MPA was located on West Fifty-fourth Street, in one of two townhouses owned by Nelson Rockefeller. It faced the sculpture garden of another Rockefeller family-inspired art institution, the Museum of Modern Art, across the street. The MPA grew out of Nelson Rockefeller's long personal collecting history of both 'primitive' and modern art and his desire to share his passion for the art.

In its charter, the MPA set out "[t]o establish and maintain a museum in the City of New York devoted to the artistic achievements of the indigenous civilizations of the Americas, Africa, and Oceania …." In the Preface to the MPA's first publication, founder and Trustee President Nelson Rockefeller elaborated on the museum's purpose:

Our aim will always be to select objects of outstanding beauty whose rare quality is the equal of works shown in other museums of art throughout the world, and to exhibit them so that everyone can enjoy them in the fullest measure.

This emphasis on the artistic qualities of the museum's collection was not accidental. Whatever advances made during the first half of the twentieth century to incorporate 'primitive' art into the larger art historical canon, by the museum's founding in 1954 a case for its inclusion still needed to be made. From its earliest exhibition in 1957 to its last in 1975, the museum's exhibits called attention to its own acquisitions and important private collections. (All of the museum's publications are available in Watson's Digital Collections here, and you can read this In Circulation post to learn more about how they were digitized.)

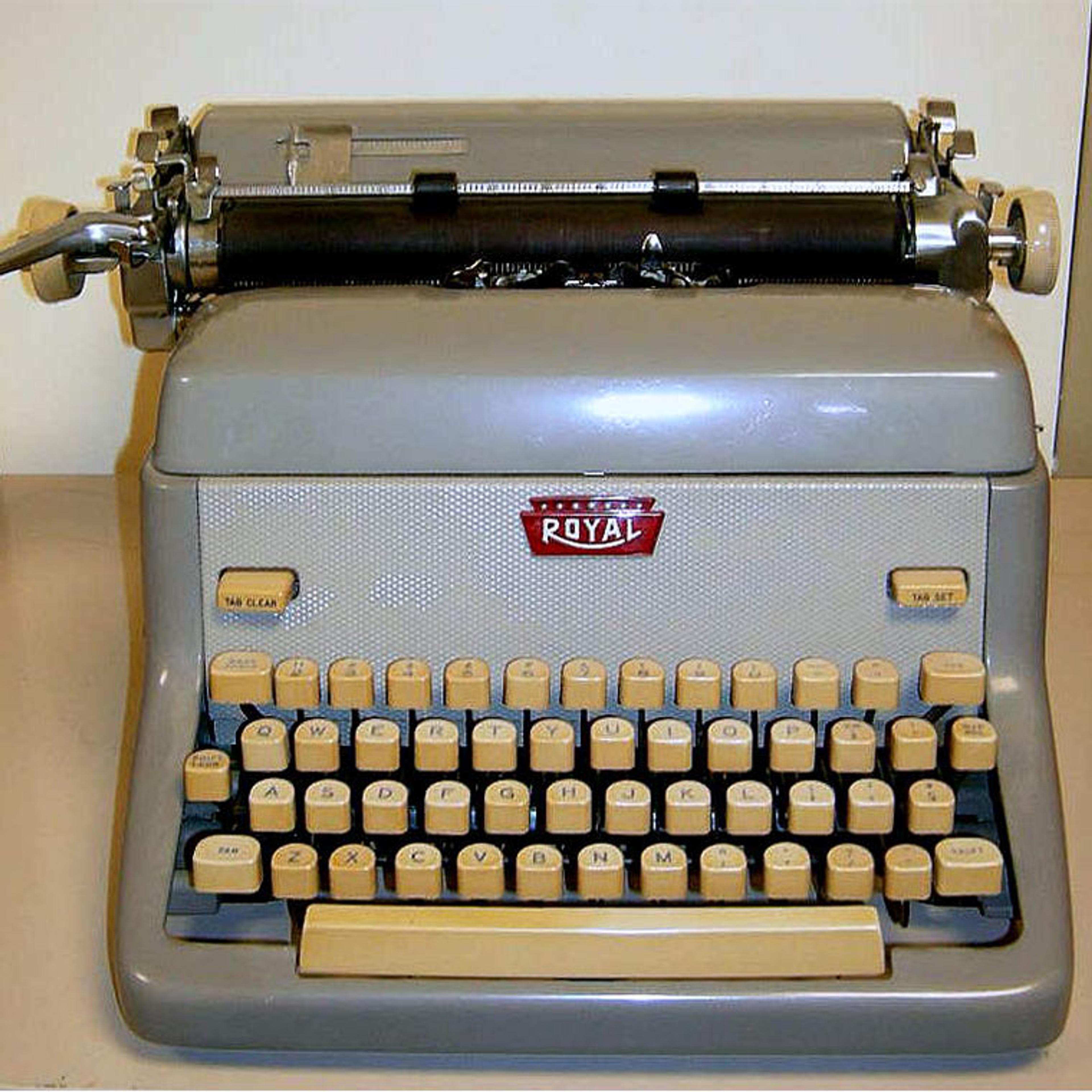

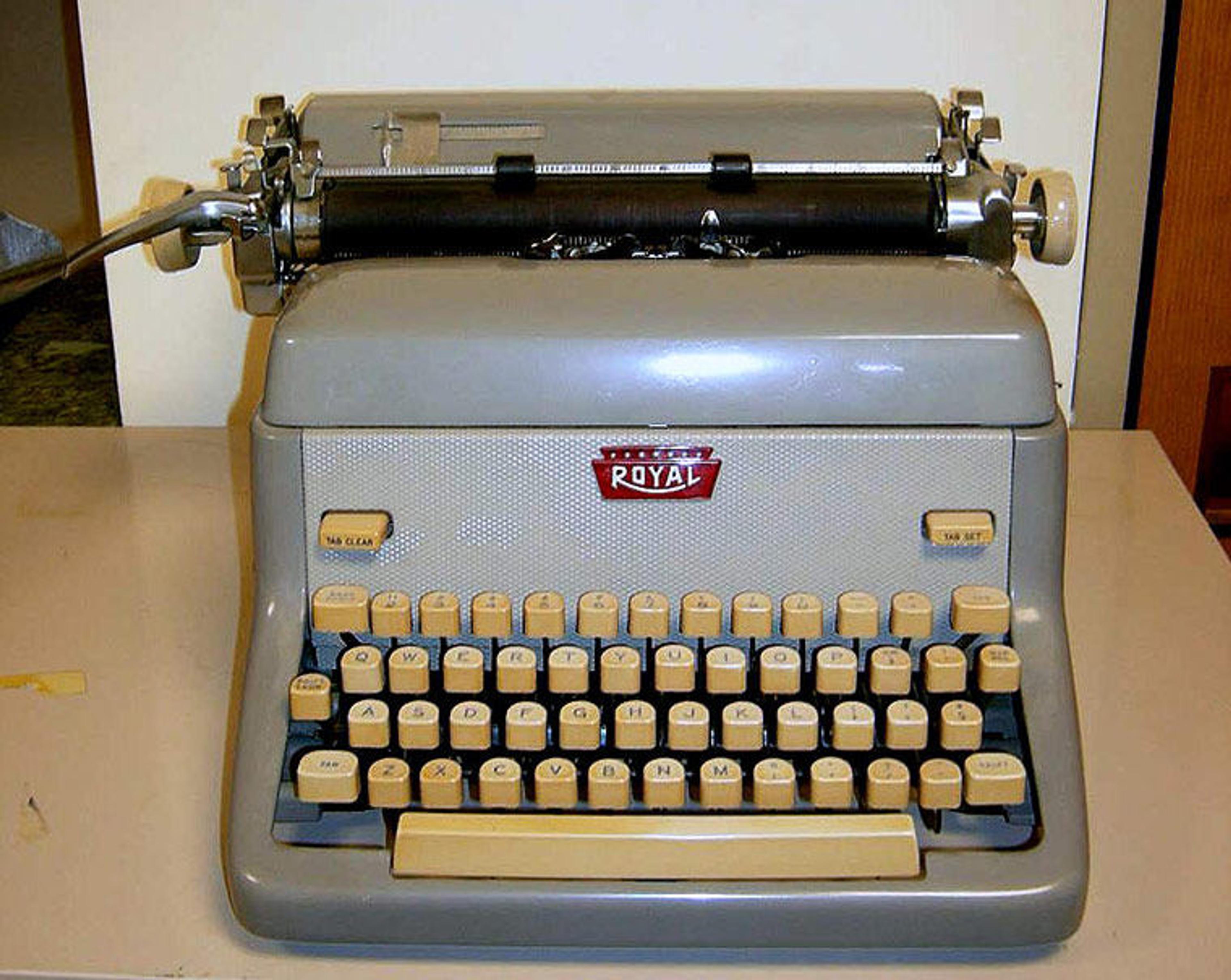

Allan Chapman's typewriter. Photo by author

The Museum of Primitive Art Library was created in 1957. According to Allan Chapman, the founding librarian and my professional mentor, the library began with fifty books and a lamp. "The typewriter would come later," he would always add when relating the library's origin myth. Judging from the bookplates I've discovered in some copies, some of the library's early collection 'migrated' across Fifty-fourth Street, from the Museum of Modern Art Library. Given the close institutional and personal ties between the two museums, this re-appropriation can probably be overlooked.

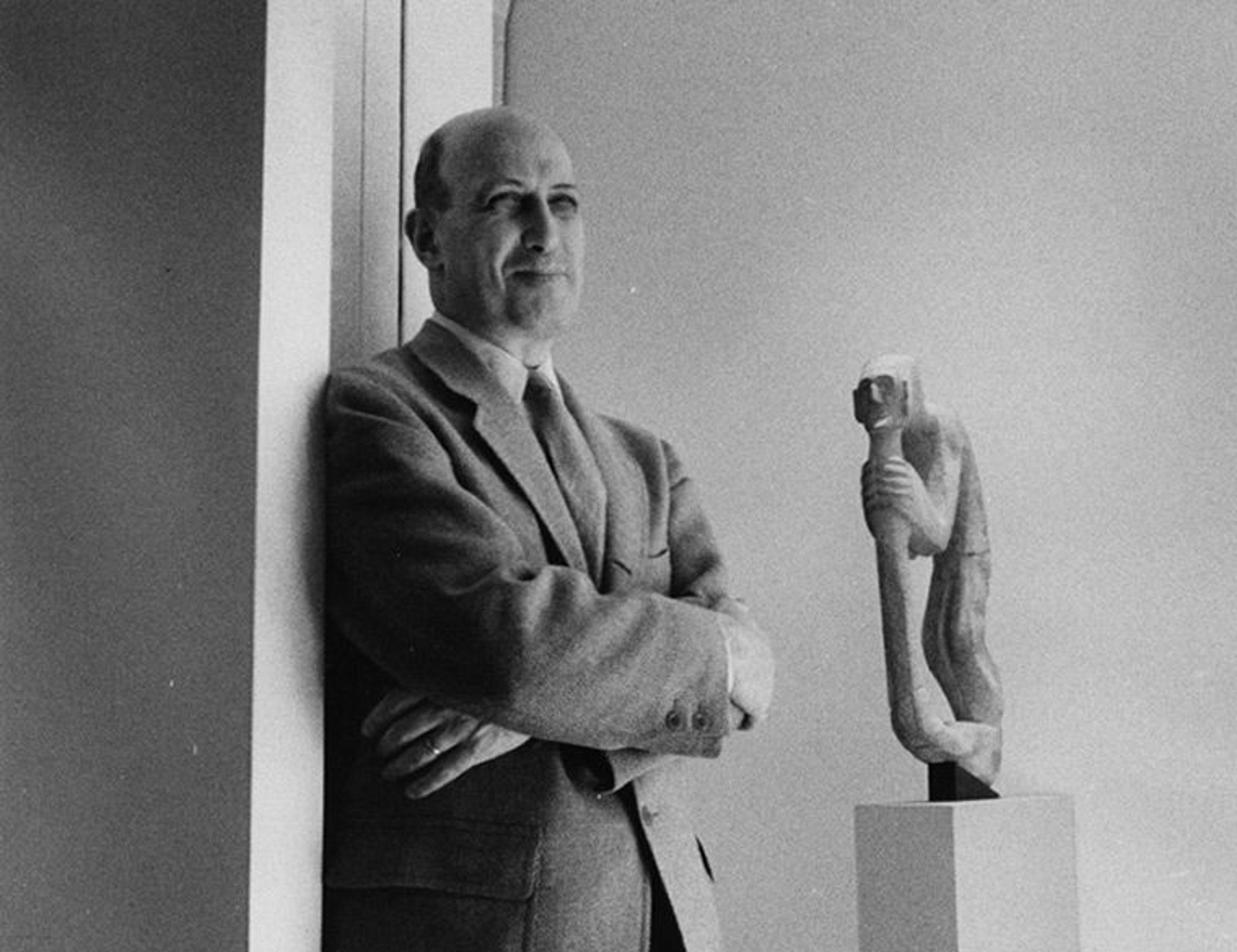

Robert Goldwater (1908-1972). (From The Nelson A. Rockefeller Vision.)

When the MPA closed in December 1974, its library, staff, and thirty-five hundred works were transferred to the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at The Met—The Museum of Primitive Art became the Department of Primitive Art; and the library, the Department of Primitive Art Library. Even then, the pejorative term 'primitive art,' which never accurately described the scope of the collection, had fallen out of favor. Recognizing this, Allan Chapman suggested renaming the library in honor of Robert Goldwater (1907–1973)—pioneering art historian, distinguished professor at New York University, and, as the first director of the Museum of Primitive Art, a much-revered former colleague. (Goldwater's other claim to fame is as the husband of artist Louise Bourgeois.) Thus renamed, the library reopened to researchers in 1982 at the same time as the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing opened to the public.

Interior of Robert Goldwater Library, ca. 2000. Can you spot the author?

Allan Chapman would retire in 1988 after twenty-nine years with the library. That year I took over directing the library. With the reorganization and consolidation of the Museum's departmental libraries in 2009, The Goldwater Library became acephalous (one of those words learned on-the-job) and I moved 'downstairs' to Watson Library to oversee its acquisitions. The staffing change has not prevented the library from continuing to add significant contemporary and retrospective titles to the collection, while enjoying all the mutual benefits of institutional collaboration.

The Collection

Untitled illustration from Antiquities of Mexico: Comprising Fac-similes of Ancient Mexican Paintings and Hieroglyphics (London : Printed by James Moyse... : Published by Robert Havell... and Colnaghi, Son, and Co. ..., 1831-1848.) (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

When Chapman first began to build the library collection, relatively few books were published which treated 'primitive art' as art. The library includes a vast number of non-art titles—on subjects such as discovery and exploration, archaeology, anthropology, ethnology, sociology, philosophy, economics, and law. Back when I still shelved books, sometimes it seemed the library had as many titles on headhunting as on totem poles. The reason for this emphasis is unsurprising: the study of 'non-Western' art has always focused on understanding the art as much within its social context as for its aesthetic qualities. Researchers, collectors, and admirers alike seek answers to questions such as: Why was this object created? Does it carry out a specific ceremonial, social, or political function?

As dated, misguided, and even crude as these early written works may seem to us today, viewed through a correcting prism they are often the sole contemporary record of traditional artistic practice. It all goes to understanding the context of the objects to all observers, not only to its creator and the community for which it was created, but to everyone who looks on that work.

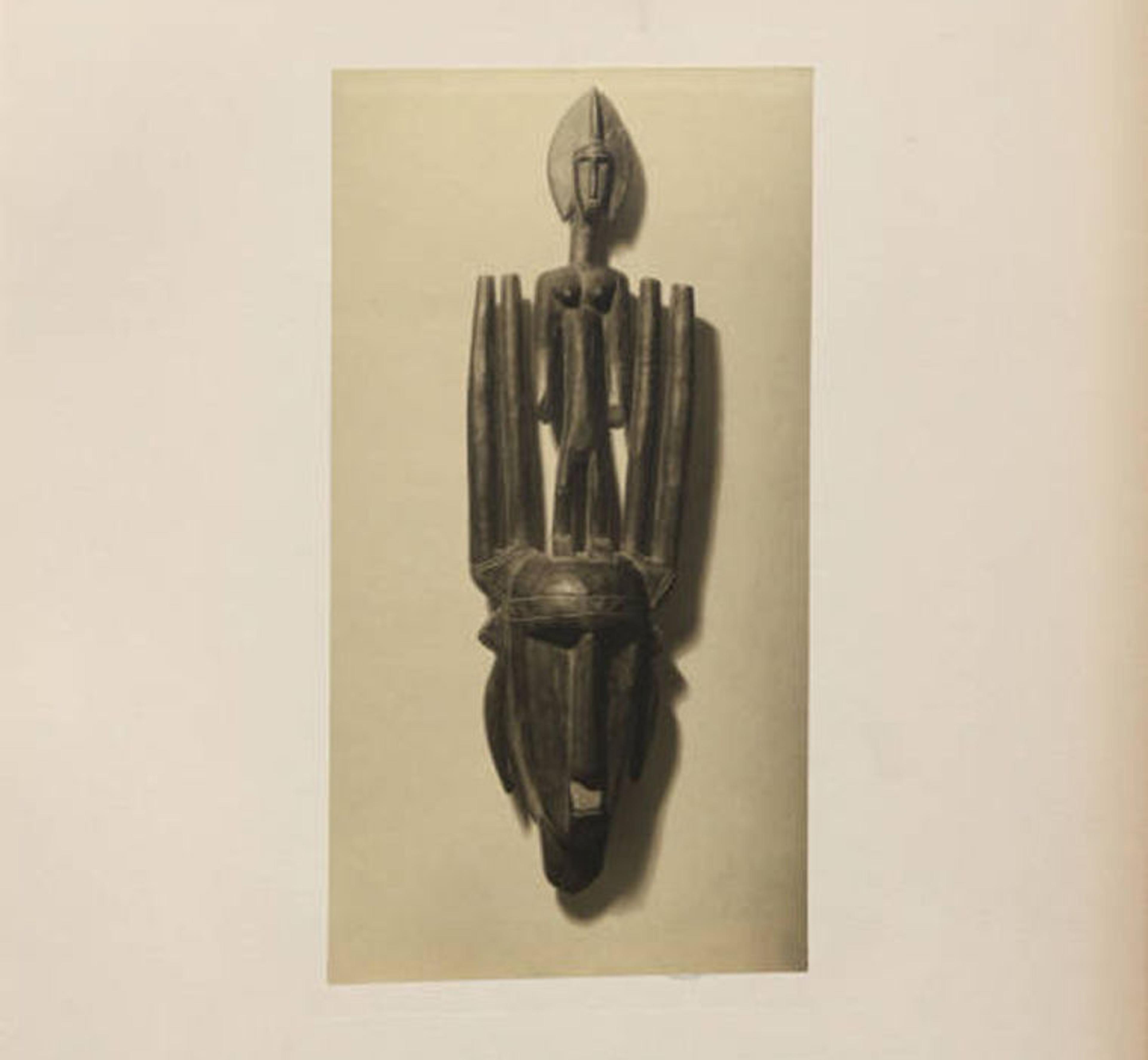

Untitled plate from African Negro Sculpture (New York?: [s.n.], 1918)

Slowly at first, books began to appear in the early twentieth century that speak without qualification to these works as art in their own right. One seminal example is Charles Sheeler's African Negro Sculpture, a limited-edition portfolio of original photographs that marries Sheeler's modernist aesthetic and traditional African art.

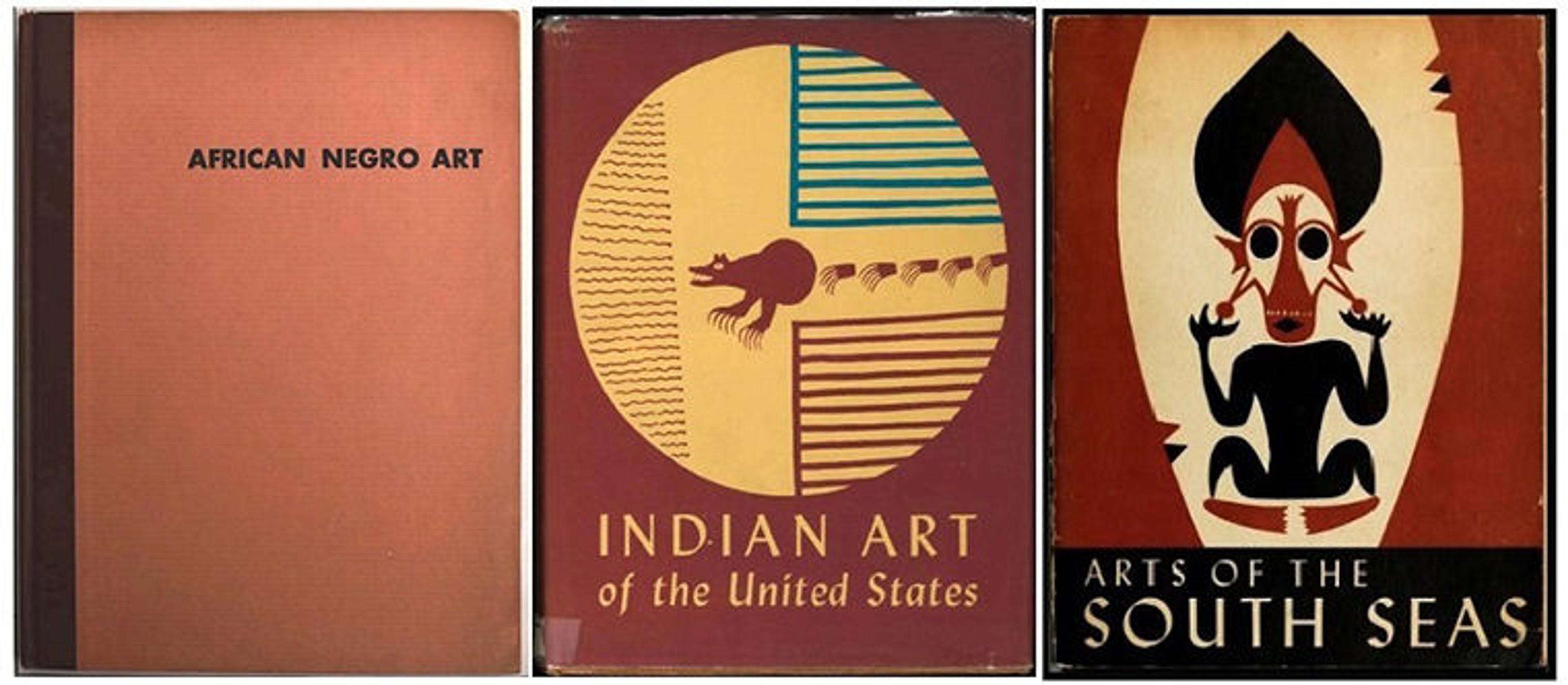

Three ground-breaking exhibitions: African Negro Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1935); Indian Art of the United States (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1941); and Arts of the South Seas (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946)

Three mid-century exhibits (and their accompanying catalogues, shown above) at the Museum of Modern Art brought attention to 'primitive' art to a much wider audience. In many ways they are the models, in style and concept, for those published later by the MPA. Indeed, for many years Indian Art's co-author René d'Harnoncourt closely advised Nelson Rockefeller on his personal collection. These and other early titles are now darlings of the book collecting market.

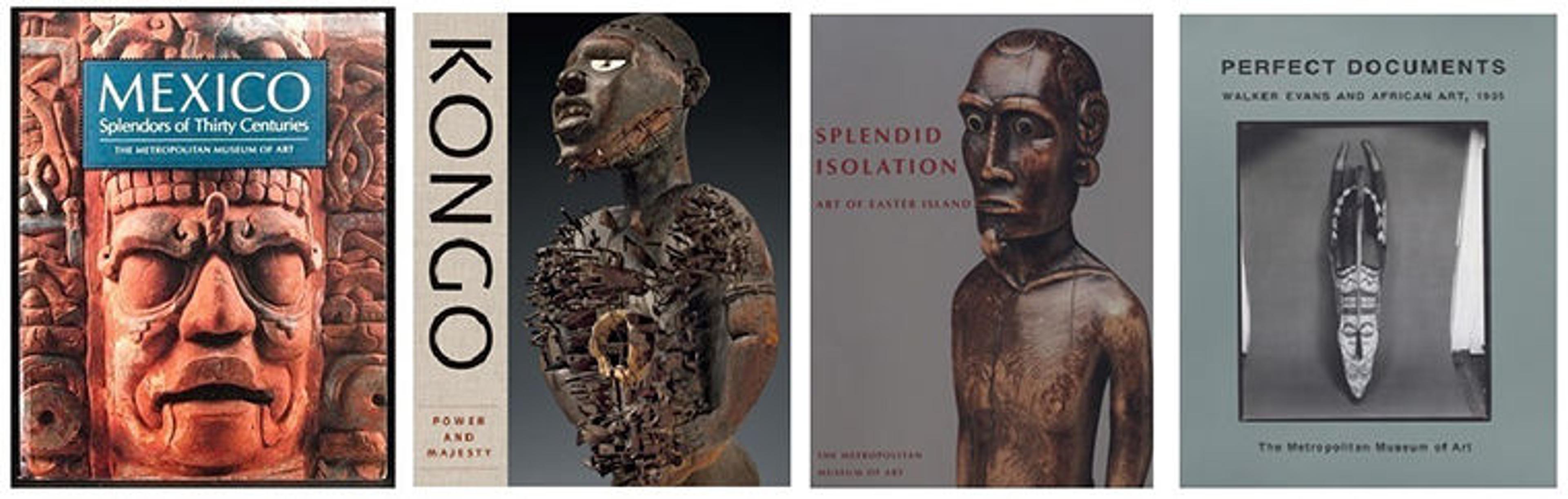

Four more recent publications: Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990); Alisa LaGamma, Kongo: Power and Majesty (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015); Eric Kjellgren, Splendid Isolation: Art of Easter Island (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001); Virginia-Lee Webb, Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art, 1935 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000).

Over my nearly forty years with The Goldwater Library, I've witnessed the fusion of the ethnological and the art historical schools of scholarship, which has had a significant impact on the character of publications. Books now place indigenous art in its much larger cultural and historical context, including internal and external influences; address issues of authorship, collecting and connoisseurship; and explore its relationship to modern and contemporary indigenous and diaspora art. Thanks to this scholarly abundance, today Goldwater Library concentrates its resources largely on collecting 'art' titles, however broadly defined.

Fittingly, the trajectory of the study of indigenous art—from self-sufficient and inward-looking outlier to full and equal participant in the international scholarly art community—echoes the story of The Goldwater Library's journey from the Museum of Primitive Art to The Met.