Contrary to what their name entails, "permanent" displays in museums are rarely static. In the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, works are regularly swapped in and out of the African galleries in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing due to loans to other institutions, conservation research performed by the Museum's expert staff, or the inclusion of new acquisitions into an existing installation. These movements often provide curators with opportunities to look afresh at works in their collection, whether it be entire sections or individual objects.

Left: Commemorative post: male (Ngya), late 19th century. South Sudan. Bongo peoples. Wood, H. 75 1/2 in. (191.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Louis V. Bell and Harris Brisbane Dick Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1973 (1973.264)

The recent de-installation of an important Madagascar work on loan for several months to the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris provided the ideal occasion to give prominence to another work in the collection: a monumental Bongo anthropomorphic post from present-day South Sudan. A tall, pole-like, and simplified human form representing a standing male figure with flexed knees, the work is the commemorative representation of a high-ranking hunter and warrior created toward the end of the nineteenth century. The gentle modeling of the body and the sensitive treatment of the face and head give the piece a simple yet natural aesthetic. The arms once held close to the body are now lost, but holes on the right side indicate that that arm had been reattached at one time. Originally accented with beads that are now missing, the figure's eyes are now defined by hollow cavities.

The new placement of this carved post in gallery 352 finally allows this work to be seen in the round and in its full length. In a previous display, its mount concealed part of the lower section that would originally have been planted in the ground to keep the post upright. The work is now positioned on an open platform.

The Bongo commemorative post in its new location in an entrance to gallery 352

As the final touch to the display, I wanted to update the label and decided to check the work's original acquisition file from 1973. There, a handwritten note on a loose piece of paper revealed unexpected information regarding the context of this work's acquisition in South Sudan that lead me to consider anew its original use.

The earliest literature on this genre of commemorative post comes from ethnographic accounts written in the 1860s, 1920s, and 1960s. In these texts, the posts, known as Ngya, are described as having one primary function: to honor an important individual after death by marking his grave. During his lifetime, a Bongo man could gain honor and prestige by successfully hunting large animals such as buffalos, elephants, lions, and leopards, or by achieving victory in combat. These funerary sculptures would have been added to the sepulture by relatives about a year after the man's death, on the occasion of a feast organized to celebrate the deceased's achievements.

These anthropomorphic posts are not intended to be naturalistic representations of the deceased, but they feature personal adornments such as bracelets and scarification patterns that can be seen as clear markers of identity. The central figure representing the honored individual was not the only sculpture adorning the grave site; it was often accompanied by representations of the man's wife, children, and sometimes even his victims. Completing the installation were abstract posts featuring series of stacked notches, which indicate the number of successful hunts achieved by the deceased. This ensemble of wooden monuments and the scale of the feast confirm the title and rank attained by the deceased during his lifetime, and ensure that he maintains that place of distinction in the afterlife.

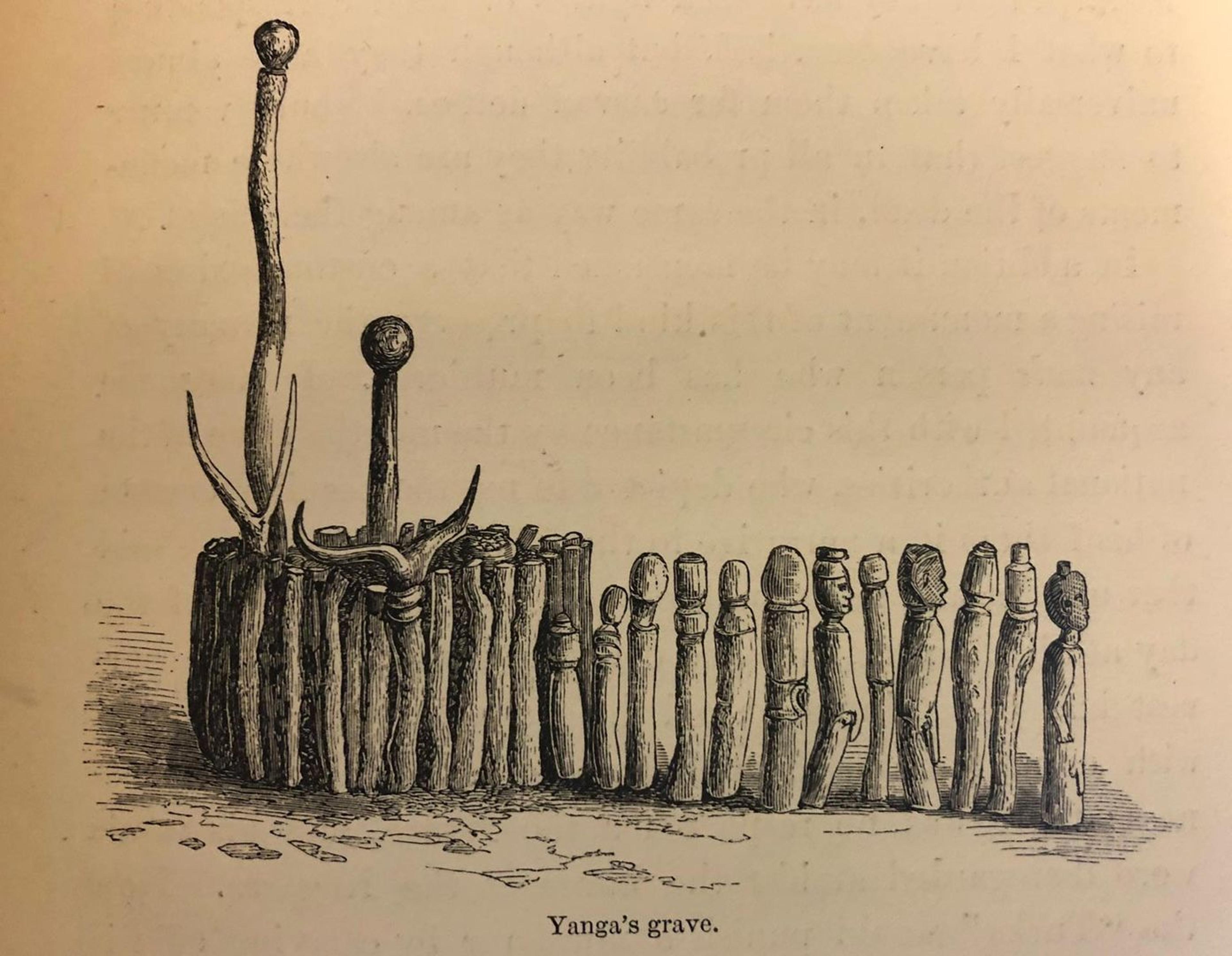

Drawing of the grave of the Bongo chief Yanga in 1869, in Georg Schweinfurth, The Heart of Africa. Three Years' Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa from 1868 to 1871 (New York, 1874), 285.

The earliest Western traveler in the Bongo region, the British consul John Petherick, had observed in 1855 "rough wooden posts, carved into semblances of human figures." In his account, published in 1861, he stated that the figures represented "the chief proceeding to a festival."[1] Not long afterwards, in 1869, the German botanist Georg Schweinfurth saw the grave of a Bongo chief named Yanga in the village of Mouhdi and learned from his informants that the figures "represented the chief followed in procession by his wife and children, apparently issuing from the tomb."[2]

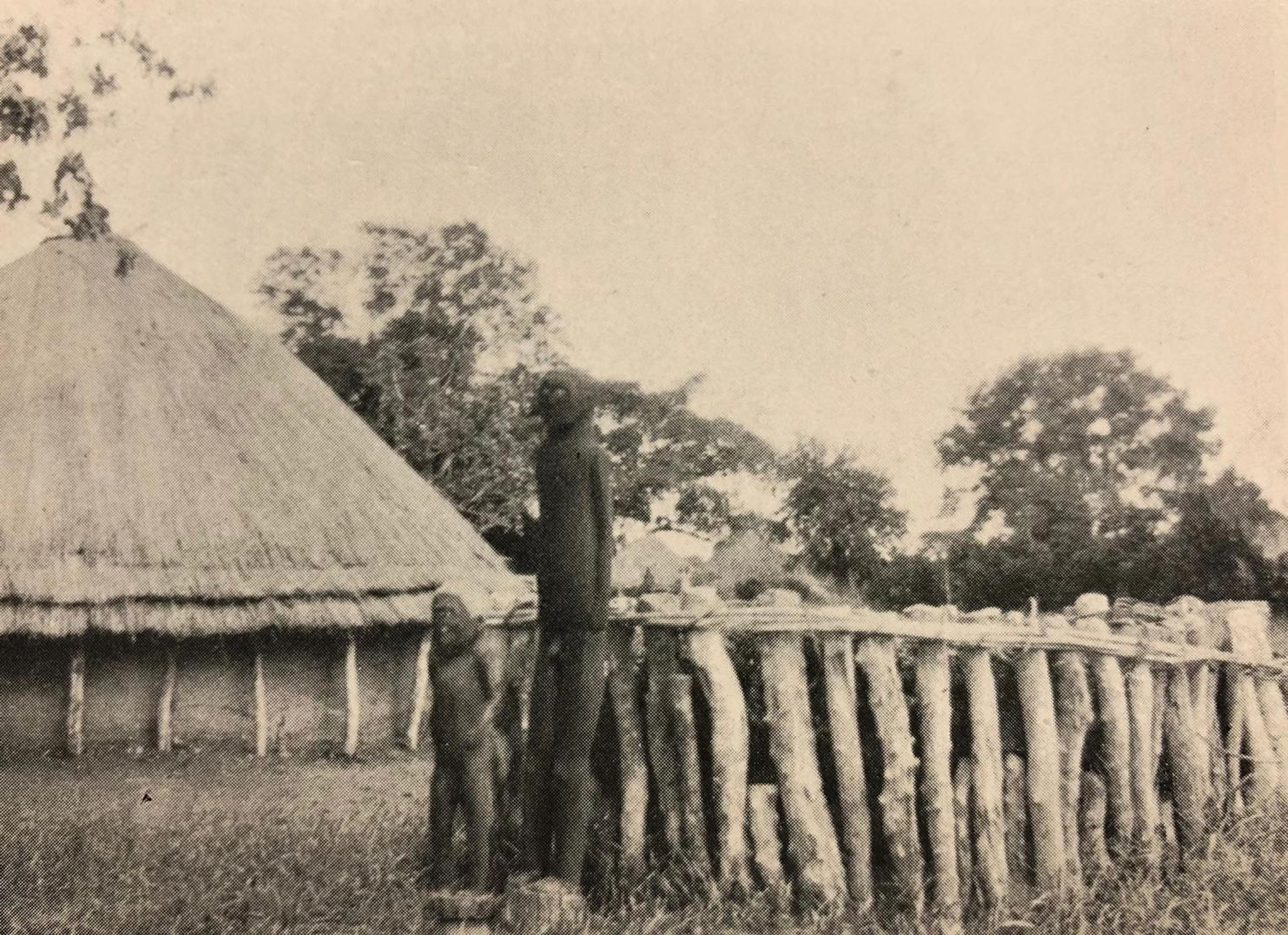

Photo of a Bongo or Mittu funerary monument, in which the sculptures represent a chief and his daughter, in C. G. and Brenda Z. Seligman, Pagan Tribes of the Nilotic Sudan (London, 1932), plate XLIX.

The first individual to publish a photograph of a Bongo funerary sculpture was the anthropologist Charles G. Seligman, in a 1917 article that featured an example in the collection of a museum in Khartoum in Sudan—a large figure described as the portrait of a deceased Bongo chief carved prior to 1886. Anthropologists Andreas and Waltraud Kronenberg carried out a detailed study of Bongo graves and monuments in 1958–59 and collected on this occasion an important group of Ngya sculptures for the Khartoum museum. Despite these repeated mentions and extensive research, South Sudan's funerary sculptures remained largely unknown in the West outside a small circle of specialists until 1972, the year of the cease-fire of a long civil war. This moment of relative peace opened the country's border to foreigners. That year, the Franco-Belgian dealer Christian Duponcheel (1941–2004) collected in and around the city of Tonj, in western South Sudan, a group of eleven anthropomorphic figures, many of which entered museum collections in Europe and the United States shortly thereafter. The work in The Met collection was part of this group.[3]

Now back to The Met's object file! It contains the standard acquisition paperwork, as well as exportation documents from Sudan and correspondence with the dealer Alan Brandt (1923–2002), who sold the work to The Met in 1973. The more unexpected part was a 1986 handwritten note by Kate Ezra, then the Museum's curator of African art, following a conversation she had with Christian Duponcheel, the dealer responsible for collecting the work, regarding the context of his acquisition and the information he gathered on that occasion.

According to this note, the work in The Met collection was not found in a funerary setting like all the others, but had been set up since before 1914 in a market in the town of Tonj where commercial transactions between Bongo and Nuer populations took place. There, it was said to help keep trade relations harmonious. Duponcheel added that the sculpture was given the name of an unrecorded Nuer ancestor. While he had taken many photographs during his stay in Sudan, he unfortunately didn't take any of this particular work. Such a placement in a busy covered marketplace explain this Ngya's distinctive shiny, polished surface. A result of extensive rubbing or handling over a long period of time, such lustrous patina could only have persisted on a work protected from the elements. The Met's Ngya is very different from the weathered and rough textures found on other known examples.

As vague as it seems, Duponcheel's recollection, and his willingness to share it with one of my predecessors here at The Met, is key in demonstrating that such figurative sculptures could be used in more diverse functions outside of a direct funerary context. Already in the 1860s, Schweinfurth had noted that the figures could be used in instances that did not lead them to be erected on grave sites. The first example was of a female carved figure, which could be kept in the house by a grieving husband to echo her living presence; the second example pertained to uncovering a murderer in cases of foul death. In this context, the carved sculpture would be presented during trial and function as a mystical apparition of the deceased, a representation close enough to being like life to scare the murderer into revealing himself. Interestingly, both statements were denied in later inquiries by anthropologist Edward Evans Pritchard in the 1920s, suggesting that these traditions had either never existed or were no longer in use, or that the ethnographer's informants no longer wanted to share information about these practices.

The information collected by Duponcheel about The Met's Ngya suggests yet another use, neither private nor judicial, but one tied to commercial exchanges between different populations in places where they intermingled such as a market. It is astonishing to think of the peaceful presence of a benevolent ancestor watching over such transactions. We can only imagine today who this individual was and what he was remembered for to have gained such a special status.

The pacifying function of this Ngya takes a deeper meaning when considering that Bongo populations have greatly suffered since the nineteenth century. They were first almost totally decimated by Arab slave traders raiding the region for slaves and ivory; later, at the start of the twentieth century, western Sudan was largely depopulated at the start of the twentieth century, when the English took charge of the political administration of the region. New knowledge regarding the context of this work's acquisition in Tonj highlights the importance of such information in moving away from generic contextualization. While each work is quite unique and has its own history, such precise information recording the context of a work's acquisition is rare. Reclaiming these histories—oftentimes an impossible feat—is essential in order to be able to tell more nuanced narratives that come closer to revealing the work's true function and deeper meaning.

Notes

[1] John Petherick, Egypt, the Soudan and Central Africa: With Explorations from Khartoum On the White Nile, to the Regions of the Equator; Being Sketches from Sixteen Years' Travel (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1861), 402.

[2] Georg Schweinfurth, The Heart of Africa. Three Years' Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa, from 1868 to 1871 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874), 284.

[3] For two extensive recent texts on Bongo funerary posts, see: Krüger, "Bongo and Belanda"; and de Grunne, Bongo: Monumental Statuary from Southern Sudan.

Resources

Coote, Jeremy. "Grave Figure." In Africa: The Art of a Continent, 137–38. London and Munich: Royal Academy of Arts, 1995.

Coote, Jeremy. "Grave Figure 'Ngya.'" In Legacy of Collecting: African and Oceanic Art from the Barbier Mueller Museum in Geneva, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, edited by Viviane Baeke. Geneva : Musée Barbier-Mueller, 2009.

de Grunne, Bernard. Bongo: Monumental Statuary from Southern Sudan. Brussels: Bernard de Grunne, 2011.

Evans-Pritchard, Edward Evan. "The Bongo." Sudan Notes and Records 12, no. 1 (1929): 1–61.

Kronenberg, A. and W. "Wooden Carvings in the South Western Sudan." Kush: Journal of the Sudan Antiquities Service VIII (1960): 274–81.

Krüger, Klaus-Jochen. "Bongo and Belanda." Tribal Arts (Winter/Spring 1999/2000): 82–101.

Schweinfurth, Georg. The Heart of Africa. Three Years' Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa from 1868 to 1871, 1st American edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874.

Seligman, C. G. "A Bongo Funerary Figure." Man 17 (June 1917): 97–98.

Related Content

Read more Collection Spotlights on the Collection Insights blog.