Whether outfitted in historical armor, lecturing on zoology at Columbia University, curating the collection of ichthyology at the American Museum of Natural History, or serving as the founding curator of the Department of Arms and Armor at The Met, Bashford Dean (1867–1928) was an undeniably tireless and remarkable figure. A prolific scholar, he authored numerous academic texts, on topics ranging from armored fish to armored Japanese warriors. Dean was an avid collector with a lifelong interest in medieval arms and armor, and he amassed one of the world's largest privately owned collections. His incomparable knowledge earned him an advisory position to the U.S. Army, where he consulted on body armor during World War I, serving in the rank of Major in charge of the Helmet and Body Armor Unit, Ordinance Department. Bashford Dean's collections of Japanese arms and armor helped form the initial core of the Department of Arms and Armor at The Met—one collection acquired via sale in 1904, a second via donation in 1914, following the creation of the department in 1912.

Arms and Armor curators and conservators are responsible for the research, preservation, and exhibition of these objects in The Met collection, as well as caring for a great quantity of material from Bashford Dean's personal and professional archives, which are also housed at the Museum. These archival holdings provide intimate access to the historical, cultural, and social contexts in which an artist or a collector lived, and in Dean's case, his personal belongings and notes breathe more life into the artworks in the collection.

One of the many great assets of The Met is the dedication of the professional staff to understanding the history and materiality of the collection objects, and the expertise of the Museum's conservators, scientists, and curators spans the breadth of artistic media. A pair of recent preservation projects to stabilize holdings from the Bashford Dean collection presents a perfect example of the professional collaborators who keep The Met's extraordinarily diverse collections preserved, exhibited, and accessible.

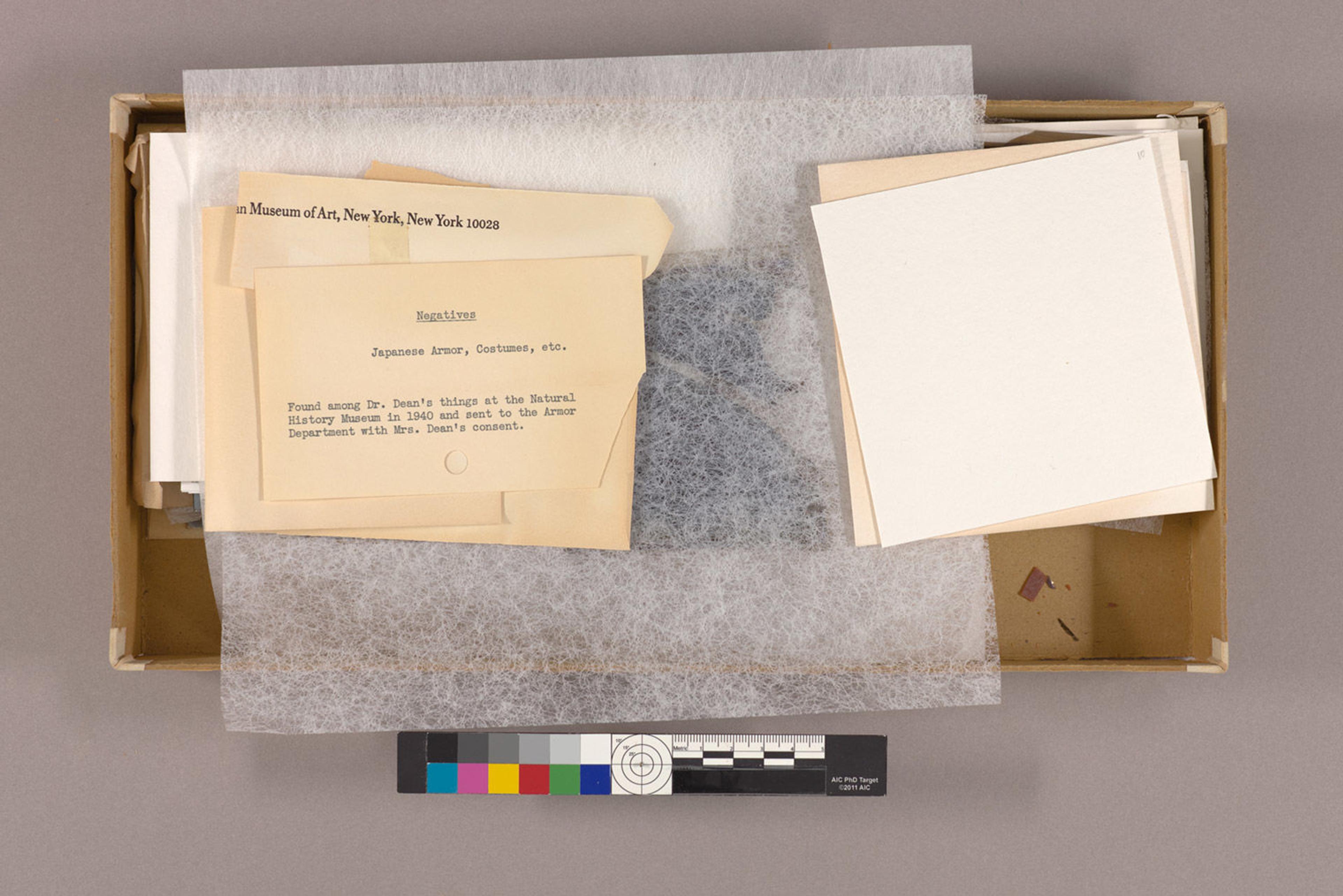

Glass plate negatives and nitrate negatives from Bashord Dean's archive, before rehousing. Photo by the author

When a box containing a group of thirteen 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 in. (12.1 x 16.5 cm) glass plate negatives and approximately sixty 3 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (8.9 x 9.5 cm) nitrate negatives was rediscovered by the Department of Arms and Armor, it was taken to the Department of Photographs and then referred on to Photograph Conservation for preservation and rehousing. The Department of Photograph Conservation works with curatorial departments throughout the Museum to exhibit outstanding photograph-based objects, provide essential preservation and conservation care for historic and documentary collections, and conduct research into the technical history of photographic images dating from the early history of the medium to the present day.

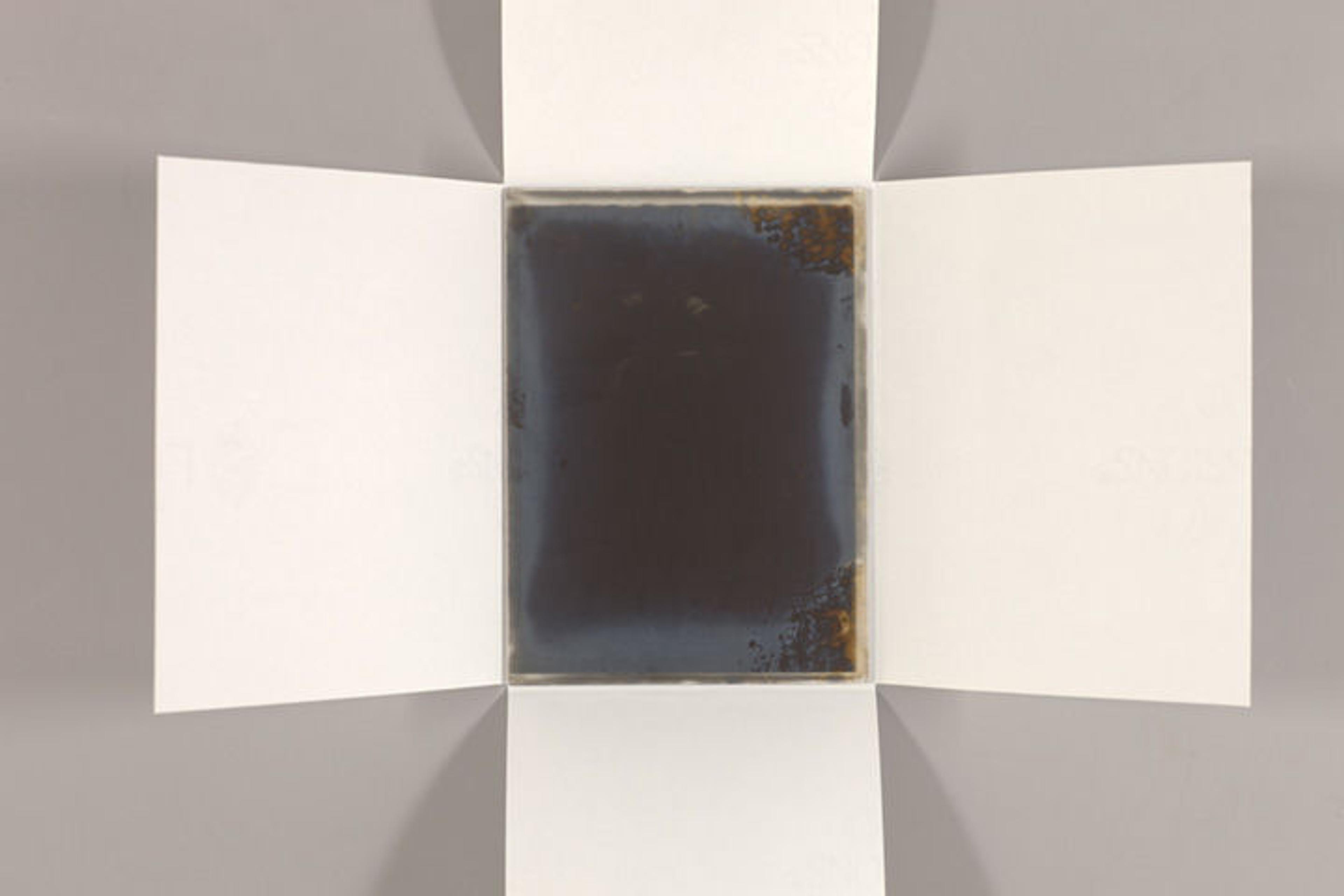

Glass plate negative in paper enclosure. Photo by the author

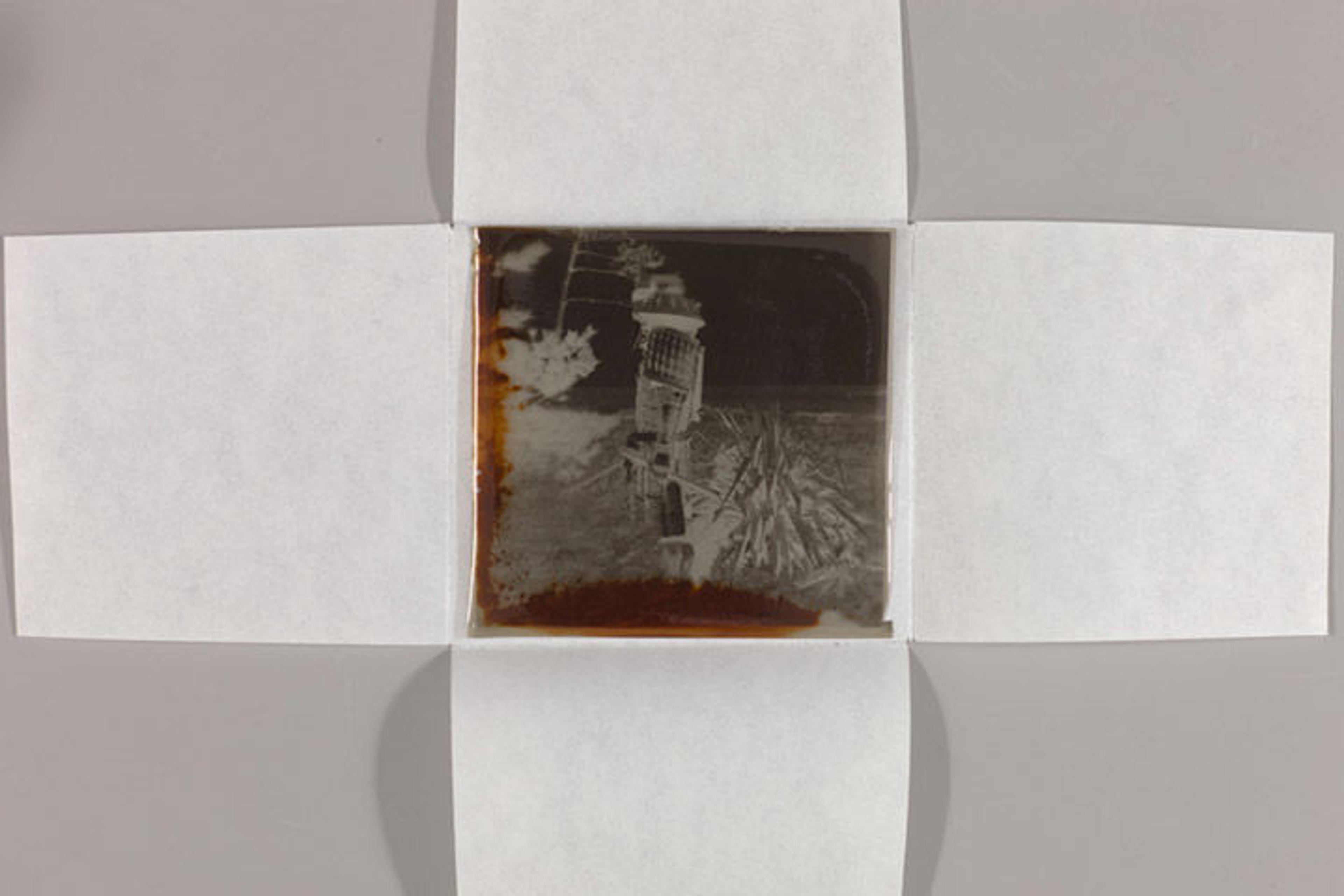

Glass plate negatives after rehousing. Photo by the author

When Dean's archival negatives, in their original cardboard box, arrived at the conservation lab—the glass plates interleaved with deteriorating paper and the nitrate negatives in a stack—the plates were all intact, neither cracked nor broken. They did, however, require imaging and rehousing to ensure their future access and preservation. This process was fairly straightforward. I imaged each negative through transmitted light, producing a secondary visual resource as well as the opportunity to digitize a more readable positive image. I then placed each original negative in an acid-free, pH-neutral paper enclosure to keep the photographic emulsions safe from contact with the adjacent negatives, and housed them all vertically in a document box.

The author, Associate Conservator Georgia Southworth, examines glass-plate and nitrate negatives following their separation. Photo courtesy the author

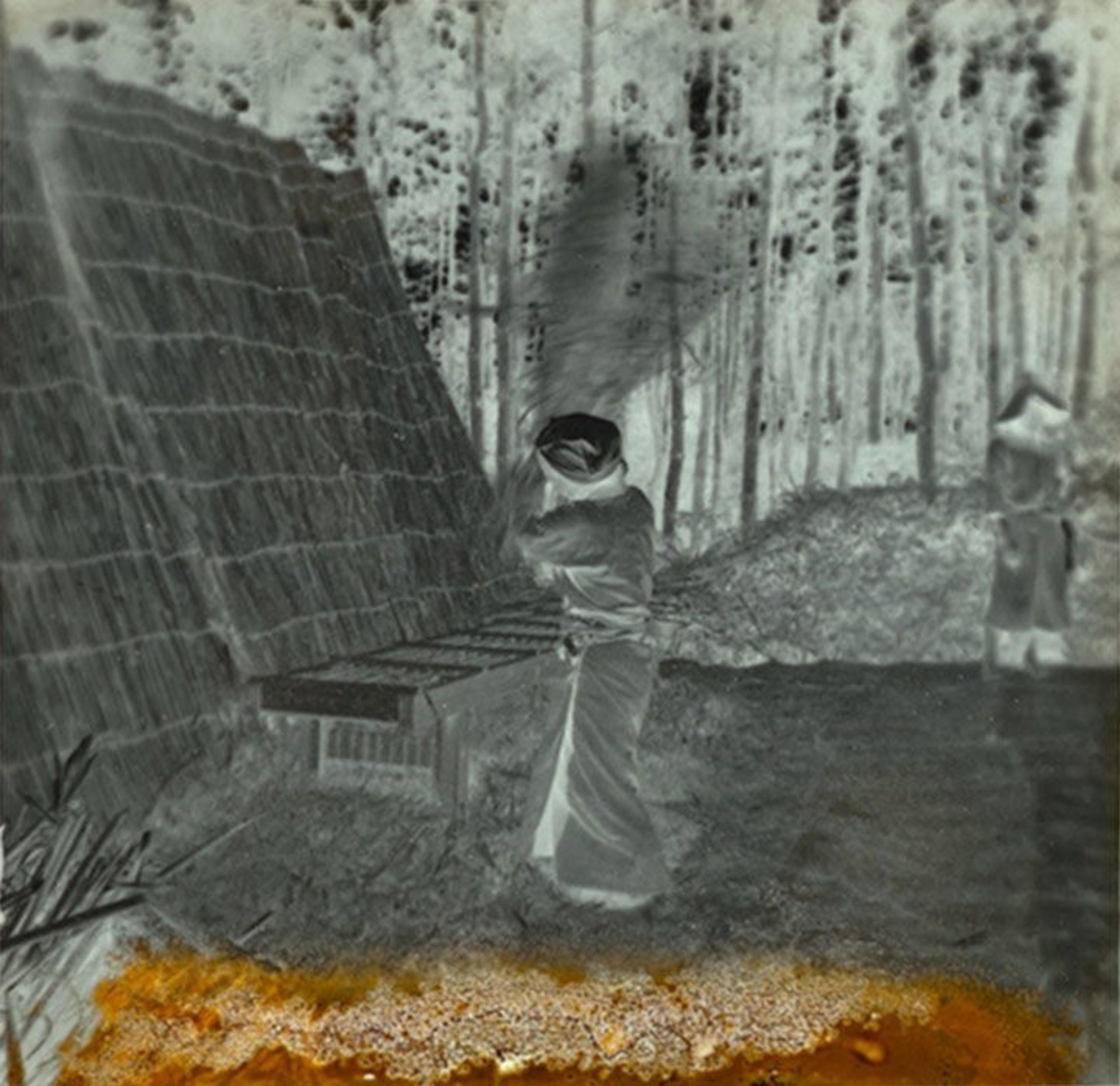

The stack of nitrate negatives, though, presented a challenging conservation dilemma. Flexible and transparent, cellulose nitrate served as a film base for photographic negatives and moving-picture film from about 1890 through 1950, when it was replaced by cellulose acetate, which is similar but physically and chemically more stable. Nitrate negatives deteriorate in distinct stages; as such, they are an ever-present concern for librarians, collections managers, and conservators.[1] A quick internet search turns up countless descriptions of the long-term instability of the material. The more advanced stages of deterioration are aptly described by Kodak:

Cellulose nitrate decomposition is the villain. It shrinks, even to the point of becoming unusable. Furthermore, as the film breaks down, it gives off nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and other gases that yellow the film base, yellow and soften gelatin, and oxidize the silver image. Later, the base cockles, becoming very brittle and then sticky. Finally, it disintegrates completely. This inevitable deterioration is usually gradual, but elevated temperatures and humidity speed it greatly.

Small volumes of these films, though, when housed in proper enclosures and stored in low-temperature settings, remain low risk. Cold storage greatly improves the long-term preservation of many photographic processes, both positive and negative, and is considered critical for nitrate negatives.[2]

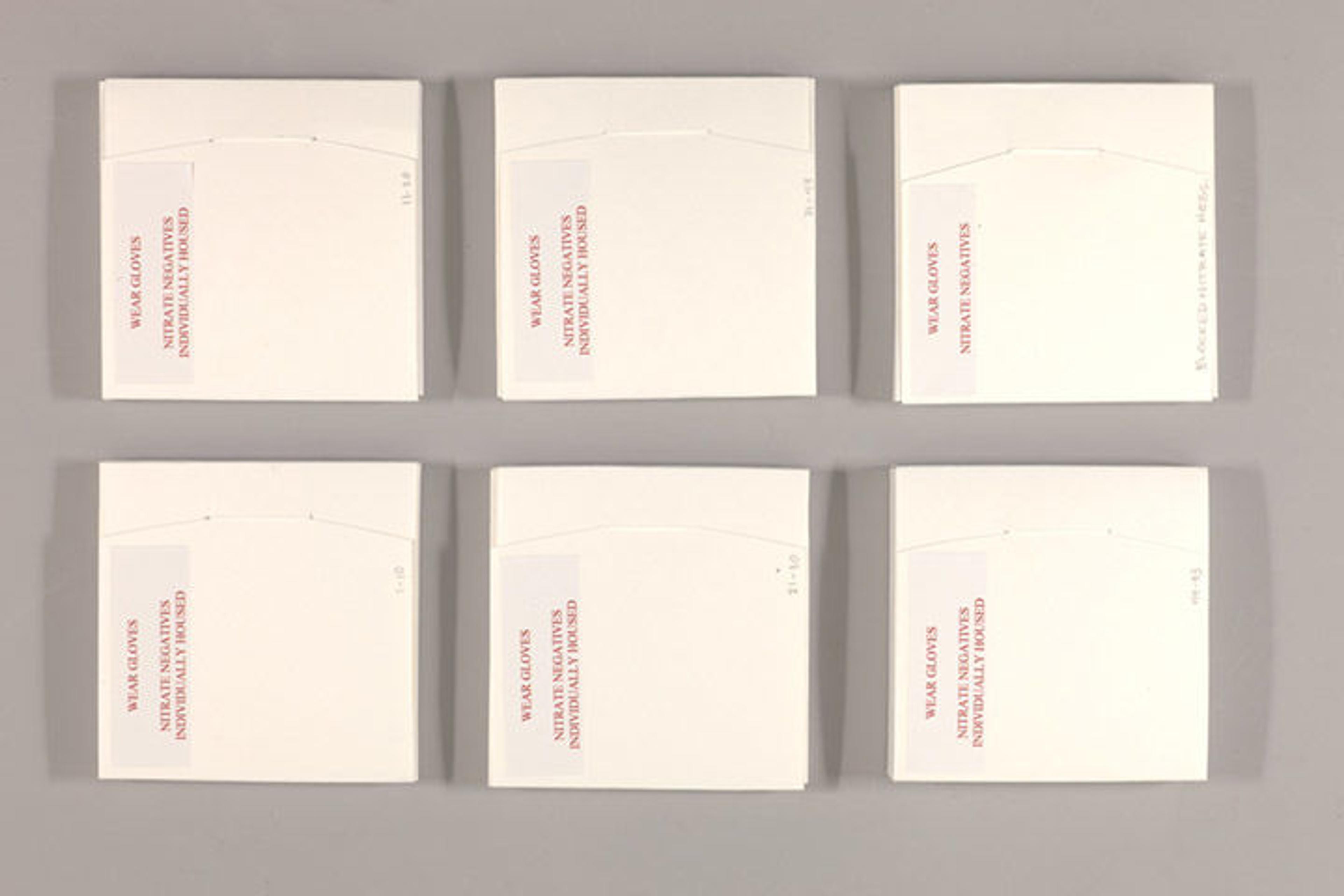

Nitrate negative in paper enclosure. Photo by the author

Nitrate negatives after rehousing. Photo by the author

Bashford Dean's nitrate negatives had been stored in direct contact with one another, and exhibited evidence of early deterioration: they presented a slight noxious odor, they had become embrittled, and were beginning to stick together, a preservation condition called "blocking." To gain access to as much of each negative as possible, I worked with Nora Kennedy—Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge in the Department of Photograph Conservation—to separate the stack of blocked negatives, millimeter by millimeter, using tools made from Teflon and Mylar.

Once separated to the extent possible, each nitrate negative—whether complete or partial—was imaged on a non-heat-emitting light box, as elevated temperature can exacerbate damage. As with the glass-plate negatives, each original nitrate negative was placed in its own acid-free, pH-neutral paper enclosure and then further housed as a group for storage. The digital image files are archived in Arms and Armor's departmental records and the Museum's backup servers, while the original negatives now safely reside in a cold-storage vault at the Museum.

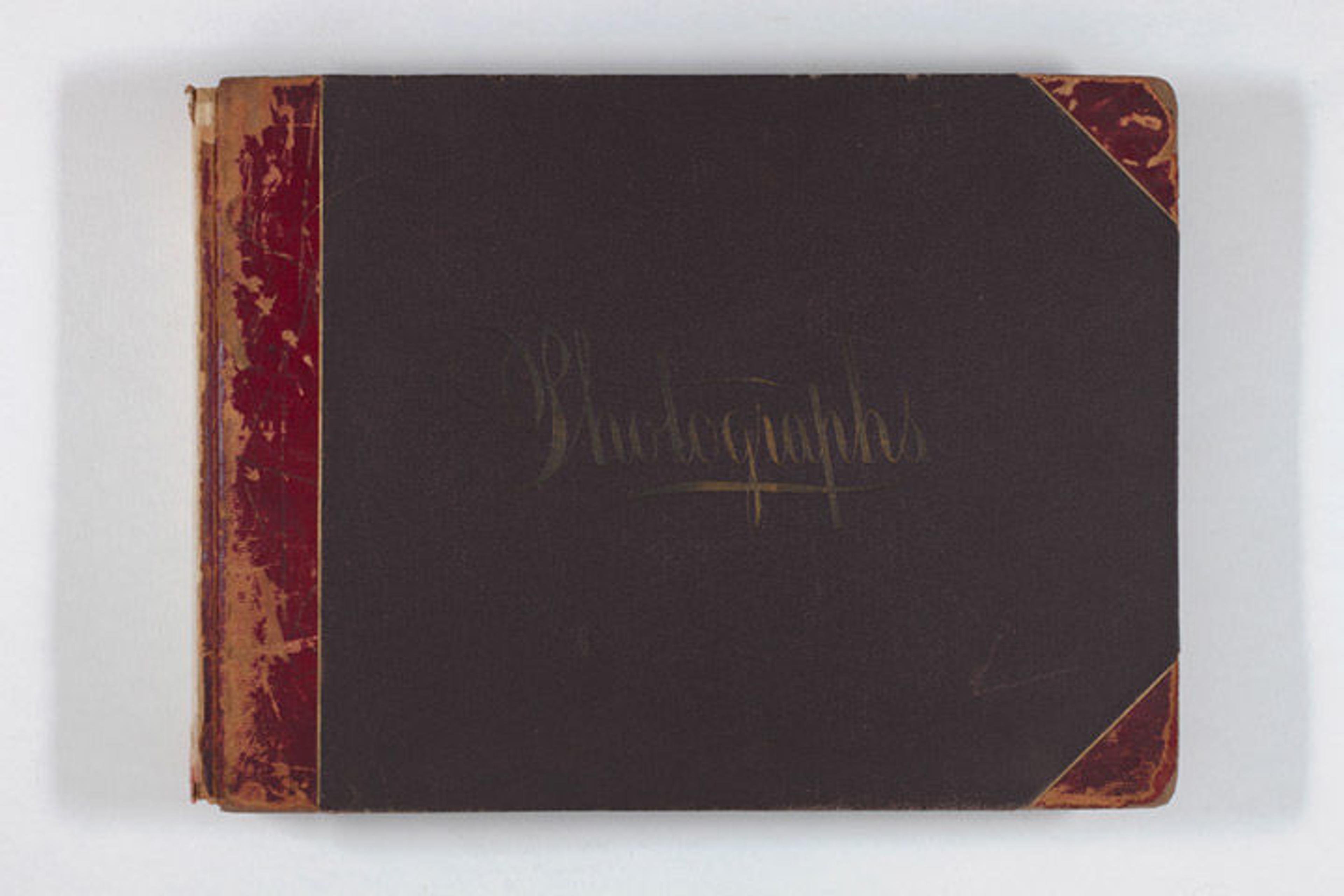

Thirteen photograph albums from Bashford Dean. Album. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Alberta Welch, transferred from the Library, 1949 (49.133.1). Photo by the author

Thirteen photograph albums from Bashford Dean. Album. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Alberta Welch, transferred from the Library, 1949 (49.133.7). Photo by the author

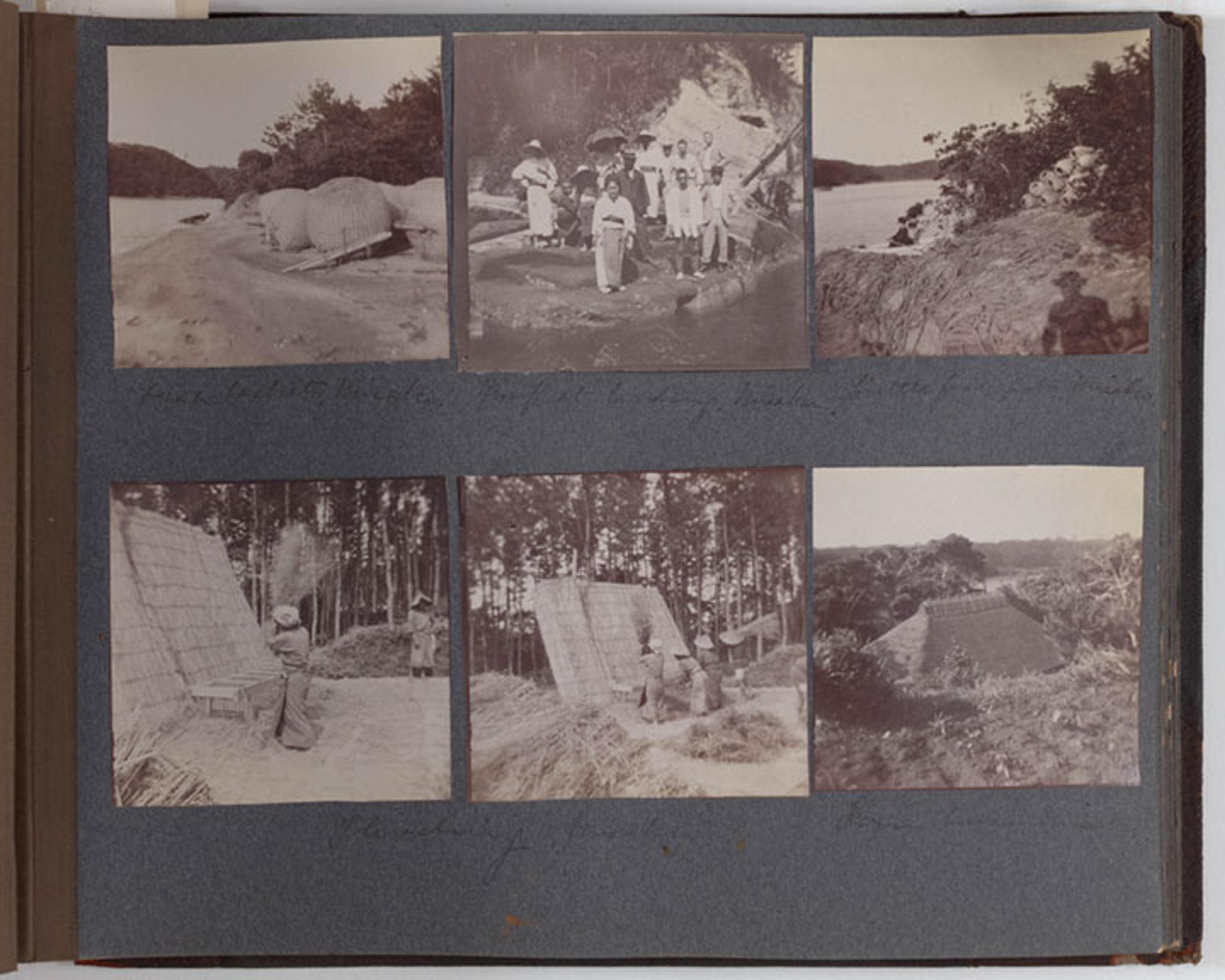

Meanwhile, in the course of researching the negatives, our preservation effort broadened when the Department of Photographs located a group of Bashford Dean's personal photograph albums in their curatorial holdings. These albums were soiled and bound in deteriorating half-leather, and as such were sequestered from the surrounding objects. Given to the Museum by Miss Alberta Welch,[3] the albums were "transferred from the Library in 1949," according to a handwritten notation in one of the volumes. Their condition made it clear that they had neither been accessed by Museum staff, nor had their contents been studied and understood. It was essential that we address their immediate preservation concerns to give curators and researchers access to the contents.

Prior to treatment, I recorded the overall condition of the albums in The Museum System (TMS), the Museum's collection-management software, and wrote proposals for future, more thorough conservation treatments. I removed the accumulated surface dirt from the volumes, working in a fume hood with a HEPA vacuum. Using various surface cleaning tools, from soft brushes to eraser crumbs, I focused on the bindings and the paper textblock supports, avoiding any contact with the photographic surfaces. To the deteriorating the leather, I applied a stabilizing solution of Hydroxypropylcellulose Klucel G in ethanol as a consolidant, and constructed a custom, chemically inert polyester wrapper and archival box for each album.

![Various artists. [Thirteen Photograph Albums from Bashford Dean]. Album. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Alberta Welch, transferred from the Library, 1949 (49.133.1–.13)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/4b1ca80aa174e76fb1a9c431b19a6e239b42a7fe-1401x1080.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

"Ural party of geologists at monument marking boundary between Europe + Asia," in thirteen photograph albums from Bashford Dean. Photo by the author

Although Bashford Dean's negatives and photograph albums remain delicate, these initial treatments have allowed scholars to access once again these historical images. Donald J. La Rocca, curator of Arms and Armor, recently viewed these images, which had been inaccessible since their arrival at The Met decades ago. With his extensive knowledge of the Museum's collection of arms and armor and its history, La Rocca recognized and provided context for various objects depicted in the photographs. When he learned the news that both the negatives and albums could safely be viewed, La Rocca replied, "We know we can identify many . . . negatives you have been working on, thanks to captions beneath the prints or their context in the albums." For example, while examining an image in one album, representing "Views of Russia [1896 or 1897] ," La Rocca noted that the photographs and captions, which describe a geological excursion to the Ural Mountains, must be the context for an object in The Met collection under the care of Arms and Armor: a medal for the Seventh Russian Mining Congress dated 1897.

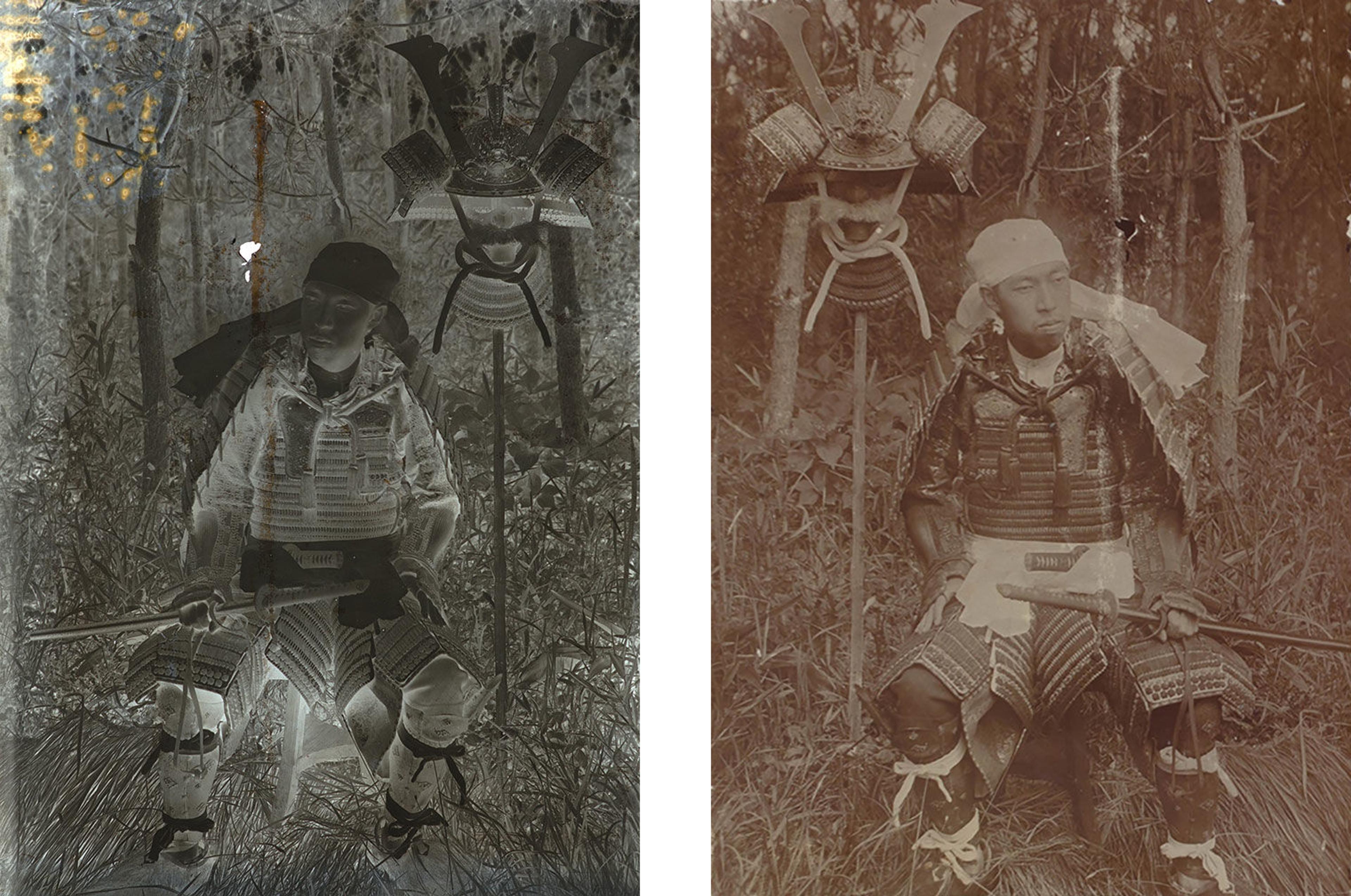

Glass-plate negative (left) and gelatin silver print (right) of a model in Japanese armor. The positive image (right) is found in thirteen photograph albums from Bashford Dean. Photos of negative and album page by the author

Research on these archival materials has shown that a number of the glass-plate negatives were used to produce gelatin silver photographs that are represented in the Museum's collection, as well as many of the images found in the pages of Dean's photograph albums. Renewed access to this cache of images provides information from which to seek answers to questions both old and new: Who are the people in the images? Are there other objects in the Museum's collection that are visually represented in Dean's photograph albums? Study of these negative and positive images prompts all manner of questions. For example, Katherine Whately, while a volunteer in the Department of Arms and Armor, conducted research into which specific cameras Dean might have taken along to document his travels, and has suggested he perhaps used a No. 2 Folding Pocket Kodak Camera or one from the Bull's-Eye Camera series. One can only speculate what further study of these images will do to enhance the curatorial understanding of Dr. Bashford Dean's remarkable life and career.

Nitrate negative (laterally reversed). Photo by the author

Gelatin silver prints in thirteen photograph albums from Bashford Dean. At lower left is the positive image of the previous nitrate negative. Photo by the author

A multifaceted rehousing effort invariably involves numerous people, and the treatment, documentation, rehousing, and storage of the Bashford Dean archival negatives and photograph albums proved no different. The author would like to thank the following members of The Met's dedicated staff for their assistance, who as team worked to determine a holistic and intra-departmental solution for the some of the fascinating objects owned by a very interdisciplinary Dr. Bashford Dean: Nora Kennedy; Nancy Reinhold; Meredith Reiss; Pierre Terjanian; Donald J. La Rocca; Ted Hunter; Katherine Whatley; Nancy Rutledge; Teri Aderman; and John Lindaman.

Notes

[1] For greater detail on these stages of deterioration, as well as a detailed discussion of all photographic negative processes and their characteristics, see: Maria Fernanda Valverde, Photographic Negatives: Nature and Evolution of Processes (Rochester, NY: Image Permanence Institute, 2005).

[2] More information about the storage guidelines for cellulose-nitrate-based film photographic processes can be found in Valverde's Photographic Negatives, at the Image Permanence Institute, and in a research bulletin published by Paul Messier, conservator of photographic materials at The Met.

[3] Miss Alberta Welch was related to Bashford Dean through his wife, Mary Alice Dean. Welch was sister to Mrs. Dean's (née Dyckman) brother-in-law, architect Alexander McMillan Welch. Mrs. Dean and her sister, Fannie Fredericka, were the two daughters of Isaac Michael Dyckman, the sixth-generation descendant of Jan Dyckman, who moved to America in 1666. Through the generations, the Dyckmans became a prominent family in New York City—magnates in real estate and business—and they established the family homestead in what is now the neighborhood of Inwood in upper Manhattan. Mary Alice married Bashford Dean, and Fannie Fredericka married Alexander Welch (brother to Alberta). The two Dyckman sisters lived and worked in close concert with one another, and in 1915 purchased back the Dyckman House at Broadway and 204th Street, which had been sold in 1868. Together with their husbands, the sisters restored the Dyckman House and donated it to New York City as an historic structure in 1916.

Related Content

Learn more about Dr. Bashford Dean on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History and on The Met's blogs.