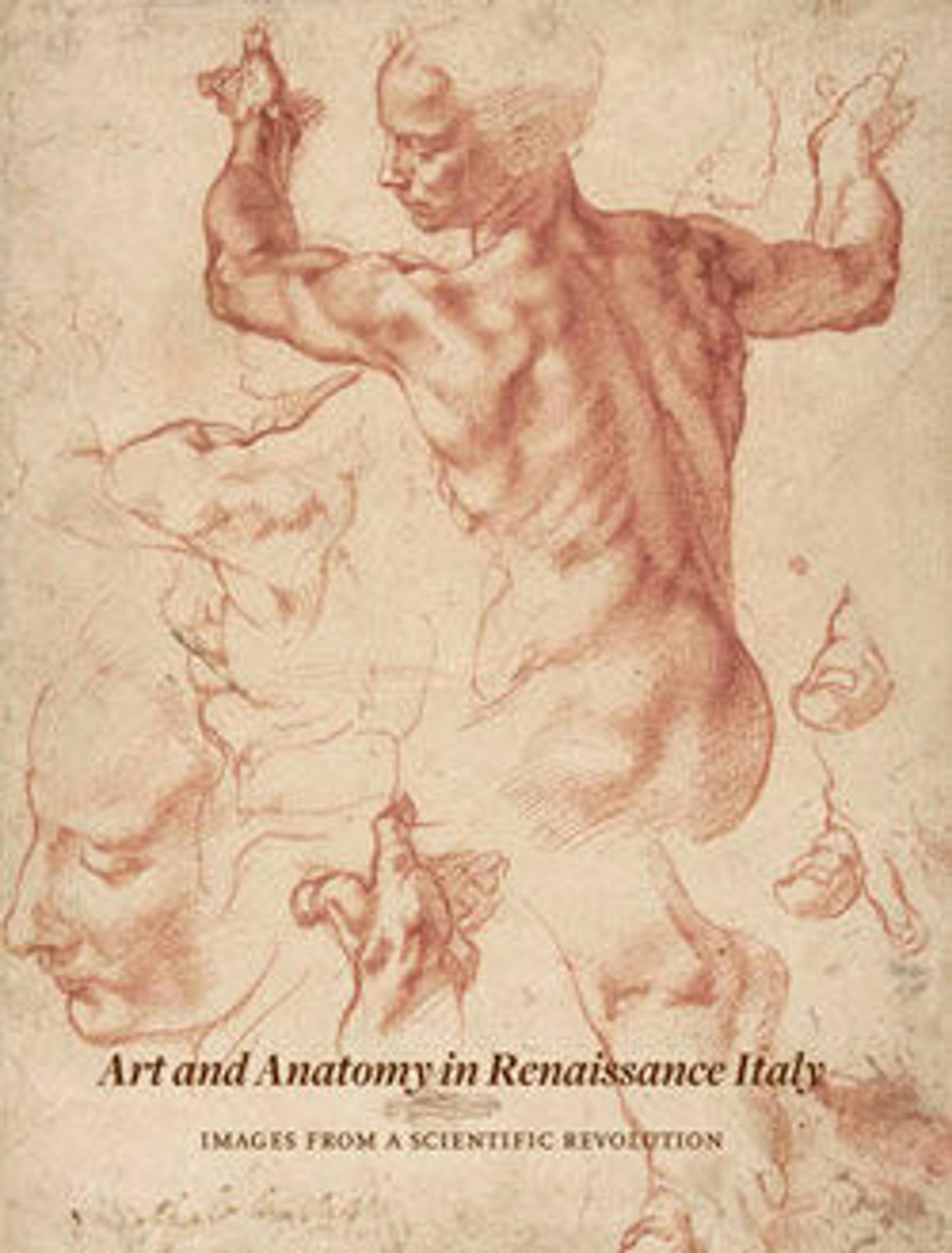

Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy: Images from a Scientific Revolution

In Italy in the sixteenth century an unprecedented and widespread interest in anatomy gave rise to a unique collaboration between science and art. Anatomists published illustrated educational treatises, and artists not only helped illustrate those volumes but also studied anatomy for their own inspiration and understanding. Their research was often the impetus for remarkable drawings and sculptures.

This issue of the Bulletin presents a succinct history of art and anatomy in Italy during the Renaissance. The author, Domenico Laurenza, is a science historian with a strong interest in art who spent 2006–7 and 2009 at the Metropolitan Museum as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow and is now affiliated with the Museo Galileo's Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza in Florence. At the Met, he was able to conduct his research with ideal resources: the Museum's collection is rare in that it contains not only scores of drawings by the greatest artist-anatomists of the Renaissance—most prominently Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael—but also anatomical manuscripts and books that are most often found in libraries rather than museums.

The opportunity to look at both kinds of documents simultaneously enabled Dr. Laurenza to understand the artists' anatomical drawings in the context of the history of science. For example, while he was studying a well-known anatomical drawing by Raphael he discovered that another, related drawing of Raphael's was almost certainly the direct source for a plate in an anatomical treatise by Berengario da Carpi, a milestone in the history of anatomy. And through its printed version in Berengario's treatise, that drawing had a bearing on one of the plates in Andreas Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica, the masterpiece of Renaissance scientific anatomy.

Berengario da Carpi was a doctor, but he was also a collector of works of art. He had a special preference for drawings, particularly Raphael's, and that penchant certainly played a role in his choice of illustrations. Similarly, the gifts of a number of other doctors who were also collectors have significantly enriched our holdings of both books and drawings.

The Metropolitan's exceptional collection inspired a 1984 study, Artists & Anatomists by A. Hyatt Mayor, Curator of Prints here from 1946 to 1966. The essay in this Bulletin complements that earlier work, as it presents many of the same drawings and documents from a scientific perspective. We are sure to benefit from Dr. Laurenza's fresh approach to this material. Indeed, it seems the very essence of an encyclopedic museum to embrace such a breadth of interpretations.

Met Art in Publication

Citation

Laurenza, Domenico. 2012. Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy: Images from a Scientific Revolution. New York : New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; distributed by Yale University Press.