The Artist: Stefano da Verona, sometimes mistakenly identified as Stefano da Zevio in the earlier literature, was among the outstanding painters in Lombardy and the Veneto in the early fifteenth century and a prime exponent of what is often termed the International Gothic Style, which is to say, art in the courts of Europe in the years around 1400. Vasari (who erroneously believed him to have been trained in Florence) praised Stefano’s work effusively, commenting in particular on "a kind of quickness of hand (

prontezza) that one sees in the figures and particularly in the heads, which are carried out with much grace." He also records Donatello’s admiration when he went from Padua to Verona (

restò maravigliato). Unfortunately, little of Stefano’s work that Vasari admired in Verona and Mantua survives; except for a group of outstanding drawings (see

1996.364a, b), there are only remnants of frescoes and two panel paintings certainly by him, the most famous of which is an

Adoration of the Magi (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) that is signed and dated 1435(?). All of which makes the discovery and attribution of The Met’s

Crucifixion in 2017 of singular importance, as it must date from early in his career and thus sheds important light on his artistic formation.

Fortunately we possess a series of documents that can be associated with Stefano.[1] He was the son of the French painter/illuminator Jean d’Arbois (Giovanni d’Arbosio or Giovanni degli Erbosi in Italian; active by 1365–died 1399), who enjoyed a widespread reputation. Arbois worked in Paris between 1373 and 1375 for Philip the Bold (1342–1404), Duke of Burgundy, and around 1420 was praised by the humanist writer Umberto Dicembrio together with Michelino da Besozzo (active 1388–1450) and Gentile da Fabriano (active by 1408–died 1427) as one of the outstanding artists of his day. Jean d’Arbois worked both in Milan and Pavia for Duke Giangaleazzo Visconti (1351–1402). It may have been when he was in Paris on behalf of the Duke of Burgundy that Stefano was born; subsequently he accompanied Philip the Bold to Bruges. Soon thereafter Jean d’Arbois returned to Lombardy (he was replaced in Philip’s court by Jean de Beaumetz). There, he was active in both Milan and Pavia,[2] conceivably working with Michelino da Besozzo (see

43.98.7). Although we possess no certain works by him,[3] he has been credited with introducing "that soft style, rich in delicate shadings and half tones, trepidatious and sentimental."[4] An idea of the quality and character of his art may be gleaned from the surviving work of his successor at the Duke of Burgundy’s court, Jean de Beaumetz (ca. 1335–1396), who in 1389 began work on a series of paintings of the Crucifixion for the Carthusian monastery of Champmol at Dijon; two of these panels have been identified (Cleveland Museum of Art and Musée du Louvre, Paris). Of great significance would be his possible identification with the person responsible for the remarkable illustrations to the chivalric tale "Guiron le Courtois" (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Ms. Nouv. Acq. fr. 5243).[5]

It was thus in Lombardy—in Pavia and Milan—that Stefano is likely to have received his training. Under Giangaleazzo, whose first wife was the daughter of the French king Jean le Bon (1319–1364) and whose daughter Valentina married Louis d’Orleans (1372–1407), Milan became one of the principal courts of Europe, with a strong francophilic bent.[6] The project to build a new cathedral in Milan, initiated in 1386, attracted artists from throughout Europe. In 1399 the French painter and illuminator Jacques Coene (active from the late 1380s–died 1411) was summoned from Paris to create a drawing of the cathedral. His presence is yet another factor to be borne in mind in understanding the rich Franco-Flemish artistic culture Stefano could draw upon.[7] It is to this international environment as well as, presumably, to his father that Stefano owes the unique and sophisticated blend of Franco-Burgundian and Italian traditions evident in the

Crucifixion.

Constructing Stefano’s Biography from Archival Sources: We know nothing about the personal life of Stefano beyond his marriage in 1399 to Tarsia d’Antoniazzo of Verona and the fact that in 1425 his household included two daughters. (He also had a son who was born in Treviso but about whom we then hear nothing.) Even his movements and activities are not easy to follow with any precision. In the documents published and discussed by Karet,[8] confusion is posed by the question of whether each time we find mention of a Stefano pittore, Stefano di Francia, Stefano di Giovanni, or even the fully named Stefano di Giovanni di Francia pittore we necessarily are dealing with the same artist or—remarkable though it might seem—whether there was another painter working in the Veneto with the same patronymic and origin. L'Occaso[9] has attempted to untangle confusion in some Veronese documents that, as he has shown, must refer not to Stefano di Giovanni but to a younger artist, Stefano di Antonio da Verona. What follows is a brief overview.

In 1394 a Stefano di Francia, an associate of a glassmaker-painter Giovanni—Zanino in Venetian dialect—di Francia (Zaninus francigena, magister vitrii specullarum sive finestrarum; a later document identifies him as a painter) and another artist, Alberto d’Alamagna, was working in Mantua for Filippo della Molza, the Gonzaga’s ambassador at the court of Giangaleazzo Visconti. Exchange of artists between the Gonzaga and Visconti courts is well documented and della Molza seems here to emerge as the probable agent of Stefano’s move from the Visconti court to that of the Gonzagas. However, it is not certain that this is, in fact, our Stefano, who would have been all of nineteen years old; L'Occaso has clarified the relationship with Giovanni di Francia and the association among the three artists involved in the documents—which had to do with a dispute over payments. These are the only documents linking Stefano to Mantua, where, however, there are remnants of a cycle of frescoes in the church of San Francesco that are cited by Vasari and are clearly by our artist, though from a much later date. The dispute regarding payment for the work for della Molza continued through 1397, by which time Stefano di Giovanni di Francia is recorded as living in Padua. Stefano’s father died in Pavia in 1399 and in that year Stefano—cited clearly as a painter and the son of the deceased Giovanni d’Arbosio—had moved to Treviso, north of Venice, where he collected the dowry for his marriage to Tarsia. He continued to reside in Treviso through 1404. Then, in 1406, we once again find a Stefano di Giovanni di Francia living in Padua and receiving a marriage dowry from the widow of a weapons dealer. Since the wife Stefano married in Treviso in 1399–Tarsia d’Antoniazzo of Verona—was still alive in 1425, when the artist and his family were living in Verona, the documents referring to his activity in Padua present a quandary for which there is no satisfactory solution: indeed, it has been argued that the Paduan documents—like the earlier ones relating to Mantua—may concern another painter.[10] Here it is enough to note that the Stefano di Giovanni di Francia in the Paduan documents became a prominent figure, acquiring citizenship, living in the city until at least 1414, and assuming a lead position (

gastaldo) in the painters’ guild. One of the Paduan documents was notarized by a well-known humanist, pointing to elite contacts. Then, from 1425 to 1434, we find the fifty-year-old artist (his age is given in the document)—this time unquestionably ours—settled in Verona, whence the name by which Vasari knew him. Indeed, most of the works mentioned by Vasari were in Verona and it was his extended activity there that accounts for the name by which he is commonly known. The paper with some of his finest drawings was made in Verona ca. 1418, reinforcing the importance of this moment, which coincides with the creation of a key work of the early Renaissance in northern Italy: the funerary monument of Niccolò Brenzoni in the church of San Fermo, with its sculpture of the Resurrection by the Florentine Nanni di Bartolo, two angels by a northern sculptor, and the whole surrounded and surmounted by an innovative fresco decoration by Pisanello. The matter of when Stefano’s work in Verona began and when he created his own mural of Saint Augustine Enthroned together with the Annunciation, in the church of Sant’Eufemia, is of interest in determining its relationship with Pisanello’s work on the Brenzoni monument (fragments of Stefano’s mural survive; its appearance is documented in a watercolor dating from 1864). The Brenzoni monument is only one piece of evidence suggesting a continuing dialogue between the two artists and explains the confusion that persists in attributing to one or the other artist works such as a

Madonna and Child in Palazzo Venezia, Rome.[11]

In 1434 Stefano is documented in Trent living in Bragher Castle: as this and another document suggest, in Trent he associated with leading families. He was still (or again) in Trent in June 1438. That October, in Verona, provision was made for the completion of an altarpiece begun by "Stefano da Verona" for the Chapel of Saint Nicholas in the church of Sant’Anastasia (but is this certainly our Stefano or rather another artist, Stefano di Antonio da Verona?).

Stefano’s activity thus stretched from Mantua and Verona north to Treviso and Trent and possibly also to Padua. Although the 1394 document relating to della Molza is important as providing a link between the Visconti and Gonzaga courts, it is also worth noting that when Giangaleazzo Visconti died unexpectedly in 1402, the ensuing political unrest led to an exodus of artists to other north Italian cities and courts—and to Venice, where, for example, we find Michelino da Besozzo in 1410. (Michelino’s work in the Veneto seems to have been extensive, as he frescoed lunettes above the Thiene family tombs in the church of Santa Corona in Vicenza.) Michelino—an artist who enjoyed immense fame—certainly provided Stefano with an important model of aristocratic stylishness and decorative brilliance in his work. There has, indeed, been occasional confusion between the work of the two artists. A case in point is an outstanding panel of the Madonna and Child with angels in an enclosed garden (Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona) that was long ascribed to Stefano—perhaps primarily because of the presence of peacocks, which Vasari says Stefano employed as his signature—but which must, in fact, be by Michelino. As The Met’s

Crucifixion makes clear, from the outset Michelino was only one of several sources Stefano drew upon. He was also much influenced by Burgundian sculpture, French goldsmith work, and Franco-Flemish miniature painting, all of which he would have seen at the Visconti court in Milan.[12] It is in this context that the presence in Milan in 1399 of the multitalented but still mysterious Franco-Flemish painter-illuminater Jacques Coene is of possible importance. As already noted, he was summoned from Paris to give advice on the cathedral and by 1404 had returned to France to work for Philip the Bold. Once hypothetically identified with the great French artist who illuminated a book of hours for the Maréchal de Boucicaut (now in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris) he has, more recently, been identified with a previously anonymous artist responsible for illuminating a missal now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (MS. Fr. 242).[13] His presence strongly suggests that apparent analogies in Stefano’s work with aspects of French miniature painting extended beyond the training of his father and have a real basis in the international culture of the Visconti court.

Stefano’s late work, as exemplified by the enchanting

Adoration of the Magi, with its landscape and carefully observed animals, shows a further evolution due to the example of Pisanello (1395–1455), who also worked in Mantua and Verona. In other words, his style evolved considerably, though it never lost its inherently International Gothic tendency toward hyper elegance and never embraced the naturalism that was to be the basis of Renaissance art. The outstanding traits of his essentially abstracting style are brilliantly evident in his drawings, with their strikingly bold pen work and actively posed figures. They evidently left a strong impression on contemporaries and were collected by that quirky humanist Felice Feliciano (1433–1479), the friend of Marco Zoppo and Mantegna. Some have been confused with Pisanello: here too issues of attribution and dating have beleaguered scholars.[14]

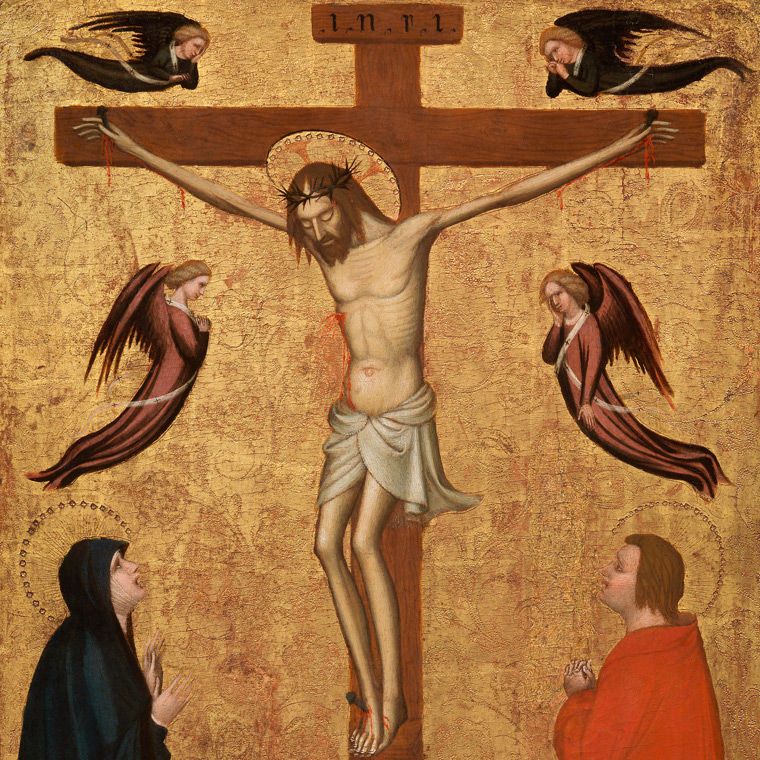

The Painting: The composition—neo-Giottesque in its austerity—is rigorously anchored by the geometry of the cross, with the elongated figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint John, the beloved apostle, positioned like statuettes on an enameled reliquary, their bodies viewed from the side, their faces shown in profile, and their gestures silhouetted against the gold background. Kneeling at the foot of the cross, her drapery pooling around her in sweeping folds, is Mary Magdalen, her gaze fervently directed upward at the crucified Christ while she simultaneously embraces the cross. Unusually, her red mantle is lined with ermine—one of several features suggesting an elite, courtly destination. The open mouths and malleable, delicately articulated hands (which recall the finest French goldsmith’s work) eloquently express grief. In contrast to these three figures, where the analogy with Franco-Burgundian sculpture is particularly pronounced, is the wraith-like Christ, his coarse-featured head hanging forward, his halo foreshortened (a feature also found in the work of Michelino da Besozzo). A further, contrasting feature is provided by the four angels, whose bodies trail off to form mirrored, symmetrical arcs. There is an analogy with the compositional procedures of Michelino—as, for example, in his 1403 illumination for the eulogy of Giangaleazzo Visconti (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris). This type of angel will be a constant in Stefano’s work and, together with the elongated bodies, the sharp-featured faces, the long-fingered hands and the small, high-arched feet of Saint John, clearly indicate Stefano’s authorship. The angels wear liturgical stoles decorated with minute crosses, crisscrossing their torsos and fluttering behind them. As explained in a detailed essay by Max Seidel,[15] these are the stoles of salvation and immortality. Finally, the gold background is exquisitely tooled with a repeating pattern of thornless roses, the emblem of the Virgin untouched by sin. Here, once again, there is an analogy of facture with goldsmith work and, specifically, reliquaries (see fig. 1 above). The panel is uncut, and the paint surface has its original raised gesso edge. There are no signs of hinges or of a means of attachment to a larger ensemble and the likelihood is that this is an independent work for a private chapel or domestic setting. To judge from its size—it is larger than might be expected for a work for private devotion—and the elegant execution, it must have been a prestigious commission.

Attribution and Date: Since the only signed and dated work by Stefano—the panel of the

Adoration of the Magi in Milan—is from his last years, and since none of the surviving fragments from fresco cycles can be related to documents, establishing a chronology and approximate date for works ascribed to Stefano remains largely conjectural. Nonetheless, the

Crucifixion, the attribution of which is supported by a detailed, morphological comparison with his drawings and two secure pictures (the

Adoration of the Magi in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, and the

Madonna and Child with Angels in Palazzo Colonna, Rome), can be dated on the basis of affinities with pictures and sculpture by other artists working in Milan in the years around 1400. The analogy with the illuminations of Michelino da Besozzo—particularly with his 1403 illumination for the eulogy of Giangaleazzo Visconti—has been mentioned. A further analogy is to be found in the sculpture of Jacopino de Tradate, particularly with his statues of mourners from the tomb of the Della Croce family (Museo della Basilica di San Ambrogio, Milan) and a scene of the Crucifixion from the carved Altarpiece of the Passion in Sant’Eustorgio, Milan.[16] Interestingly, in 1425, we find Jacopino in Mantua, underscoring the continued exchange between the two courts. Analogies with other works of sculpture carried out for the cathedral by a variety of international artists in the first decade of the fifteenth century, in which one finds a similar blend of rhythmic elaboration in the drapery and exquisiteness of detail in the figures, as well as an eloquently expressive austerity, point to a date for the

Crucifixion in the first decade of the fifteenth century.

The discovery of this important work, acquired by the German painter Franz von Lenbach (1836–1904) in the 1880s but previously unknown to the literature, adds a unique painting for private devotion to the incredibly small corpus of paintings of one of the major artists of the International Gothic movement. Its reappearance will help scholars refine their understanding of the rich artistic exchanges between northern and southern Europe at the turn of the fifteenth century.

Keith Christiansen 2018

[1] Evelyn Karet, "Stefano da Verona: The Documents,"

Atti e memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura, Scienze e Lettere di Verona 43, ser. 6 (1991–92), pp, 375–466; and Stefano L’Occaso,

Fonti archivistiche per le arti a Mantova tra medioevo e rinascimento (1382–1459), Mantua, 2005, pp. 12–13, 149–53.

[2] Inès Villela-Petit, "Propositions pour Jean d'Arbois," in

La création artistique en France autour de 1400, ed. Elisabeth Taburet-Delahaye, Paris, 2006, pp. 315–44; Roberta Delmoro, "Jean d'Arbois e Stefano da Verona: proposte per una rilettura critica,"

ACME— Annali della Facoltà di lettere e filosofia del Università degli Studi di Milano 57 (May–August 2004), pp. 121–58.

[3] But see the suggestions of Villela-Petit 2006; Albert Châtelet in "Les commandes artistiques parisiennes des deux premiers ducs de Bourgogne de la maison de Valois," in

Paris: Capitale des Ducs de Bourgogne, eds. Werner Paravicini and Bertrand Schnerb, Ostfildern, 2007, pp. 169–71; and Delmoro 2004.

[4] Laura Cavazzini,

Il crepuscolo della scultura medievale in Lombardia, [Florence], 2004, p. 6.

[5] For this, see Delmoro 2004.

[6] For an overview, see Marco Rossi, "Milano 1400," in

Arte Lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza. exh. cat., Palazzo Reale. Milan, 2015, pp. 111–19; and Emanuela Daffra and Francesca Tasso, "Filippo Maria Visconti e il corso ininterrotto del gotico in Lombardia," in

Arte Lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza. exh. cat., Palazzo Reale. Milan, 2015, pp. 173–81.

[7] For one attempt to identify the work of Coene, see Albert Chatelet,

L'âge d'or du manuscrit à peintures en France au temps de Charles VI et les Heures du Maréchal Boucicaut, Dijon, 2000, pp. 105–10; and Albert Châtelet, "Le miniaturiste Jacques Coene,"

Bulletin de la Société nationale des antiquaires de France (2000), pp. 29–42.

[8] Karet 1991–92.

[9] L'Occaso 2005, pp. 149–52.

[10] See Esther Moench, "Stefano da Verona: la quête d’une double paternité,"

Zeitschrift fûr Kunstgeschichte 49, no. 2 (1986), pp. 220–28; and Ibid., in

La pittura nel Veneto: il Quattrocento, ed. Mauro Lucco, Milan, vol. 1, 1989, p. 183 n. 43, where she comments that "The bigamy would tend to divide the person in question [i.e., Stefano di Giovanni] into two, but issues about the status of individuals and their relationships in the Middle Ages are uncertain."

[11] See Moench 1989, pp. 155–62 and 166–69 for a balanced discussion of Stefano’s place in Verona and the relationship of his art to that of Michelino, on the one hand, and to Pisanello, on the other.

[12] For an overview of the remarkable sculptors employed on the cathedral in the years around 1400, see Cavazzini 2004.

[13] On this, see Châtelet 2000 ("Le miniaturiste Jacques Coene").

[14] The most thorough analysis is that of Evelyn Karet,

The Drawings of Stefano da Verona and his Circle and the Origins of Collecting in Italy: A Catalogue Raisonne, Philadelphia, 2002.

[15] Max Seidel, "Sanctissima Imperatrix," in

Giovanni Pisano a Genova. exh. cat., Genoa, 1987, pp. 125–43.

[16] For these, see Cavazzini 2004, pp. 88–90.