Vessel with water bird and hieroglyphic text

Not on view

The front of this vessel shows a graceful waterbird, likely a heron or long-necked cormorant, balancing on one leg in the center of a cartouche. The edges of the cartouche are formed by dotted scrolls and leafy vegetation that, for the ancient Maya, represented droplets of water and aquatic plants. A naturalistic scene materializes from these deeply carved elements, in which the heron wades through a body of water, using the talons of its lifted leg to grasp at the leafy vegetation unfurling into the cartouche from the left while it lowers its head toward the plant.

A hieroglyphic inscription providing information about the vessel’s function and use runs in a diagonal band along the back. The first half of the text reads yuk’ib ta tzih kakaw, “it is his cup for fresh (or pure) cacao.” The second half identifies the owner, who holds the Maya noble title of sajal, a term reserved for lower-level elites. The text’s diagonal orientation hints at the importance of interaction for understanding the vessel: the glyphs only become vertical when the drinker tilts the cup back to drink the fresh chocolate beverage inside, making the inscription more legible to companions of the person drinking. This also suggests that these vessels were meant to be used in social settings where multiple people could engage with them.

The dark chocolatey brown ceramic used to create this vessel indicates that it belongs to the Chocholá style. This group of ceramics comes from the northern Yucatán Peninsula, likely from the region surrounding the ancient site of Oxkintok, located southwest of modern-day Mérida. Vessels of this style were deeply carved rather than painted or incised; this carved nature lends them easily to comparison with other Maya art forms, such as carved stone monuments and wooden lintels. The inscriptions found on these ceramics note that they were used for savory chocolate drinks as well as atol, a corn-based drink still popular today in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and many other countries.

Catherine Nuckols, 2025

Further Reading

Grube, Nikolai. “The Primary Standard Sequence on Chocholá Style Ceramics.” In The Maya Vase Book, by Justin Kerr, Vol. 2. Kerr Associates, 1990.

Hull, Kerry. “An Epigraphic Analysis of Classic-Period Maya Foodstuffs.” In Pre-Columbian Foodways, edited by John Staller and Michael Carrasco, 235–56. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2010.

Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso, Ana García Barrios, and Raúl Morales Uh. “Hallazgo de Fragmentos Cerámicos de Estilo Chocholá Con Jeroglíficos En Oxkintok, Yucatán.” Estudios de Cultura Maya 52 (2018): 105–16.

Stuart, David. “Sourcebook for the 29th Maya Hieroglyphic Forum, March 11–16, 2005.” Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas at Austin, 2005.

Tate, Carolyn. “The Carved Ceramics Called Chocholá.” In Fifth Palenque Round Table, edited by Virginia Fields, 123-133. San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Institute, 1983.

Werness-Rude, Maline Diane, and Meghan Rubenstein. “Making It a Date: Positioning the Chocholá Style in Time and Space.” Recent Investigations in the Puuc Region of Yucatan, edited by Meghan Rubenstein, 127-46. Archaeopress, 2017.

References

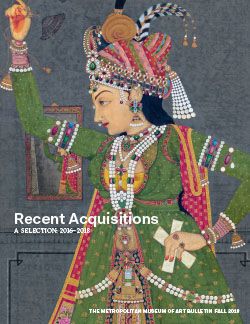

Recent Acquisitions: A Selection, 2016–2018. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018, p. 13.

Coe, Michael D. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: Grolier Club, 1973, p. 123.

Werness, Maline Diane. “Chocholá Ceramics and the Polities of Northwestern Yucatán.” University of Texas at Austin, 2010, Fig. 22.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.