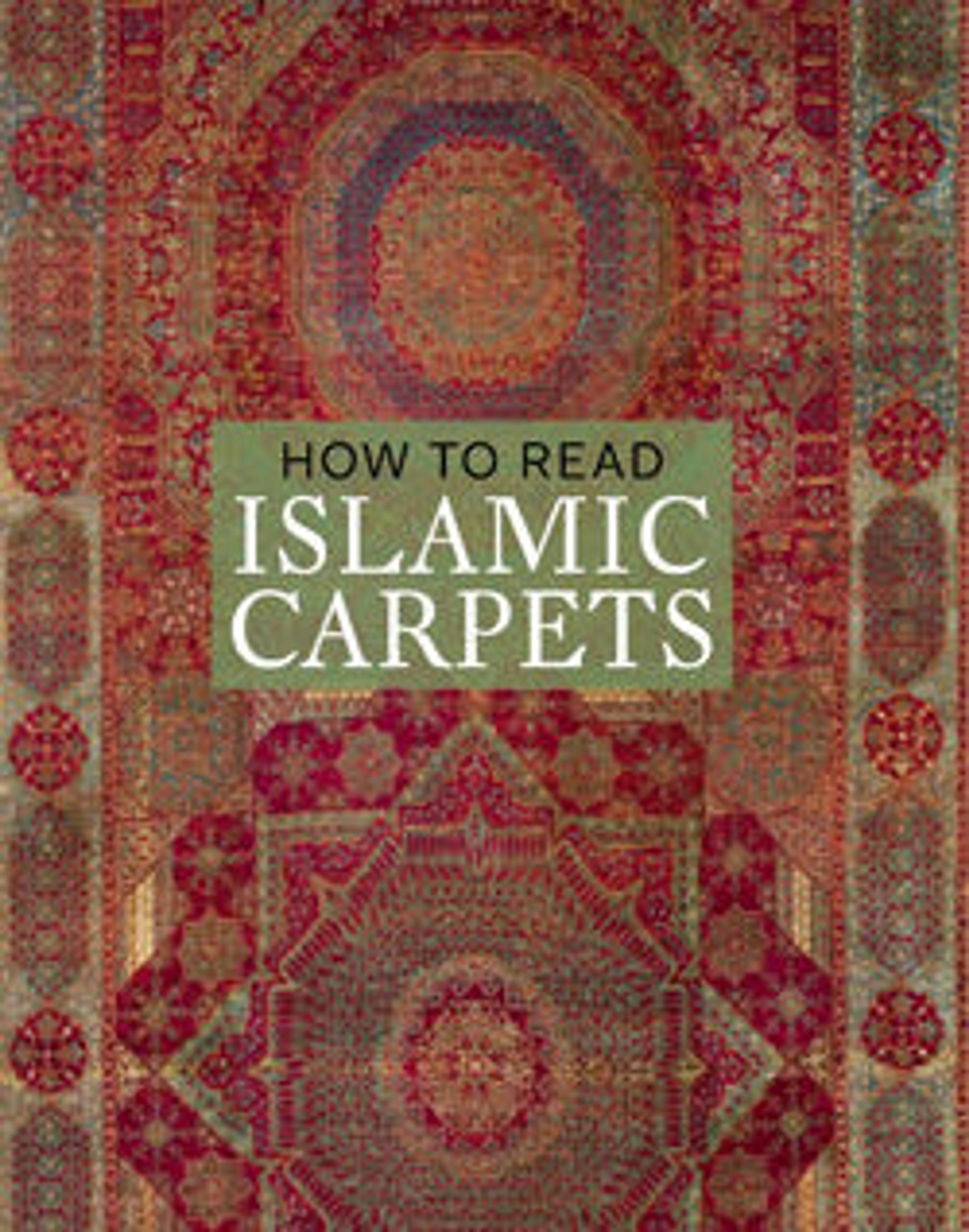

Carpet with Irises, Tulips, and Other Flowering Plants

Flowering plants, especially favored by Mughal artists, frequently appear in carpets. Here, the drawing of the flowers and the shading of the leaves are rendered with great care and as naturalistically as possible. Yet nature is disregarded when two unrelated flowers grow from the same stem.

Artwork Details

- Title: Carpet with Irises, Tulips, and Other Flowering Plants

- Date: ca. 1650

- Geography: Made in India or present-day Pakistan, Kashmir or Lahore

- Medium: Cotton (warp and weft); wool (pile); asymmetrically knotted pile

- Dimensions: L. 170 in. (431.8 cm)

W. 81 3/4 in. (207.6 cm) - Classification: Textiles-Rugs

- Credit Line: Purchase, Florance Waterbury Bequest and Rogers Fund, 1970

- Object Number: 1970.321

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.