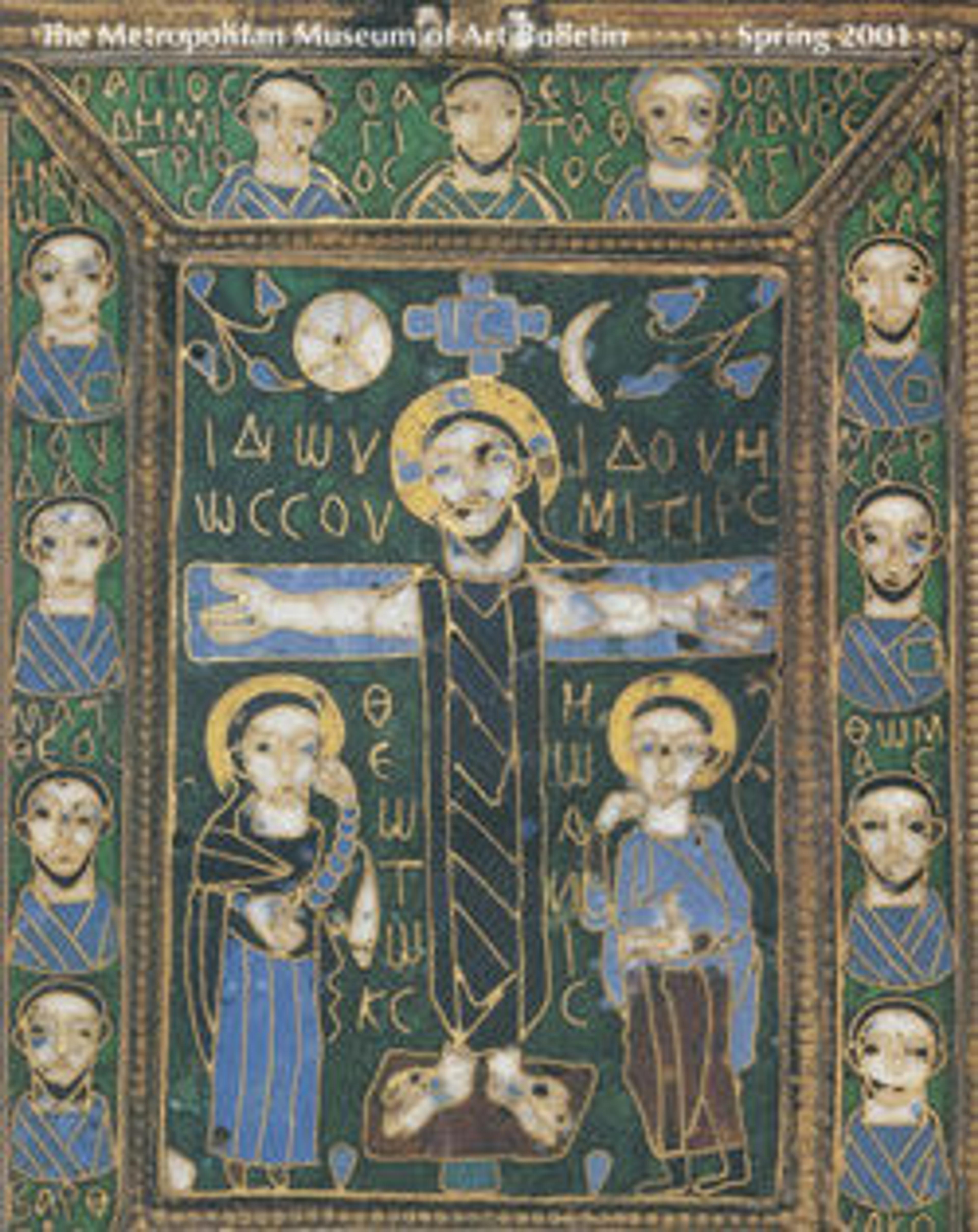

Hanging with Dionysian Figures

Leafy tendrils frame twelve (originally fifteen) busts of satyrs, maenads, and others who attended the wine god Dionysos during his thiasoi, or revels. His tutor, Silenus is the bald man at the lower right. Herakles appears as the bearded man at upper left. The two figures with horns in the second row may be Pan and one of his sons who, according to Nonnus of Panopolis, assisted Dionysos in his conquest of India. The women are amongst the maenads who attended him. These mythological figures are typical of the continuity of interest in classical learning and culture in the Byzantine world, including Egypt.

Artwork Details

- Title: Hanging with Dionysian Figures

- Date: 5th–7th century

- Geography: Said to be from Egypt, Antinopolis

- Medium: Linen, wool; tapestry-woven

- Dimensions: Textile: L. 25 1/2 in. (64.8 cm)

W. 58 in. (147.3 cm)

Mount: H. 41 1/4 in. (104.8 cm)

W. 62 3/4 in. (159.4 cm)

D. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm) - Classification: Textiles-Woven

- Credit Line: Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1931

- Object Number: 31.9.3

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.