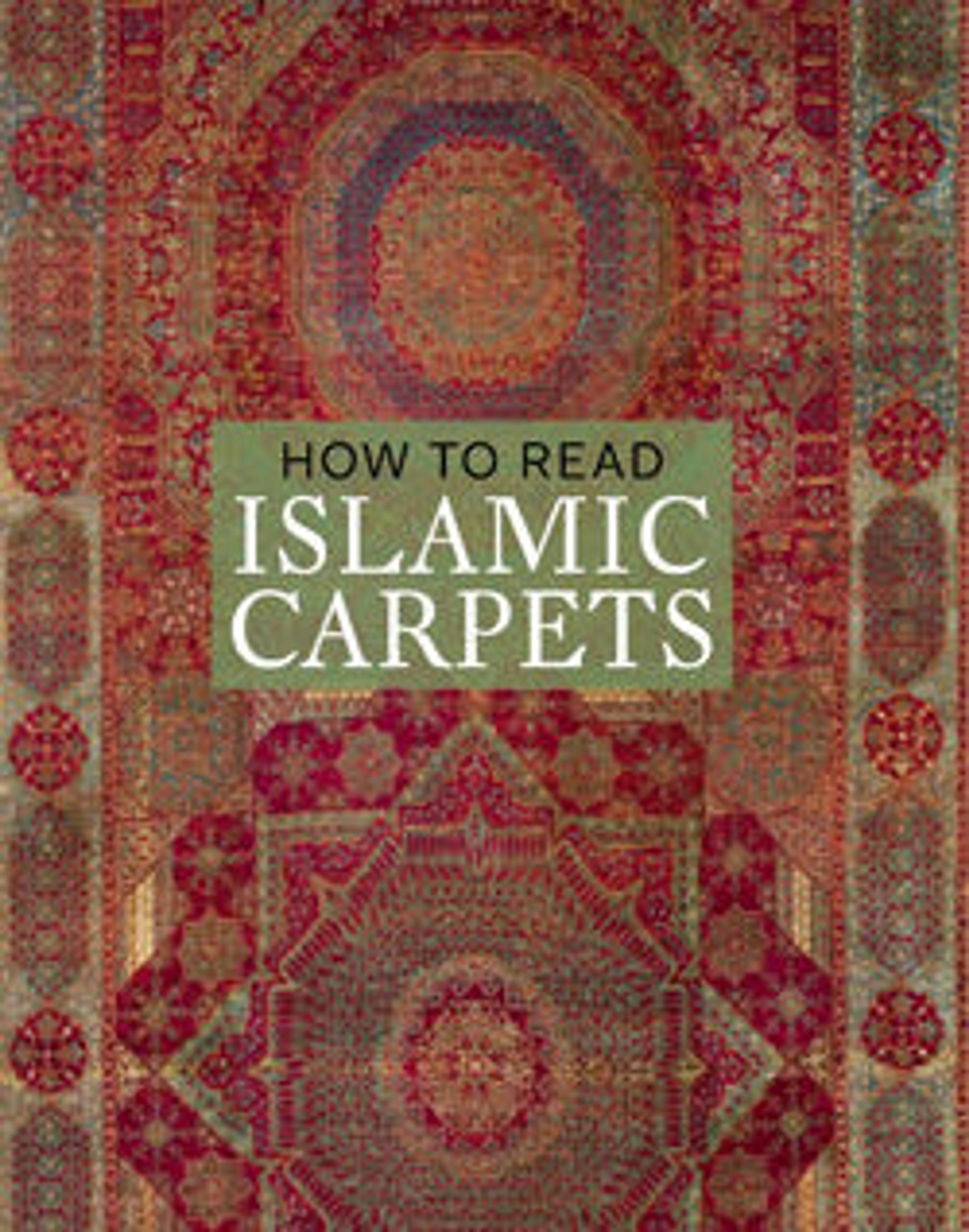

Carpet with Triple-Arch Design

This carefully drawn, subtly colored carpet is among the finest of all Ottoman weavings. One of the earliest carpets to include a triple-arched gateway, its design probably originated in the Ottoman imperial workshop. The hanging lamp in the center arch recalls verses from the Qur'an that liken God to the light of a lamp, placed within a niche. The combination of this carpet’s imagery, high quality, and relatively small size suggest that it was used as a prayer rug by a member of the Ottoman courtly elite.

Related link:

Link to Discover Carpet Art Website

Related link:

Link to Discover Carpet Art Website

Artwork Details

- Title: Carpet with Triple-Arch Design

- Date: ca. 1575–90

- Geography: Attributed to Turkey, probably Istanbul

- Medium: Silk (warp and weft), wool (pile), cotton (pile); asymmetrically knotted pile

- Dimensions: Rug: L. 68 in. (172.7 cm)

W. 50 in. (127 cm)

Mount: L. 71 in. (180.3 cm)

W. 53 3/4 in. (136.5 cm)

D. 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm)

Wt. 120 lbs. (54.4 kg) - Classification: Textiles-Rugs

- Credit Line: The James F. Ballard Collection, Gift of James F. Ballard, 1922

- Object Number: 22.100.51

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.