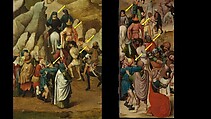

The Painting: One of the most dramatic episodes of the Passion of Christ relates how Jesus struggled beneath the heavy burden of the cross as he made his way along the route to Golgotha, the “place of the skull” and the site of his eventual crucifixion. The New Testament Gospels of Matthew (27:31–33), Mark (15:26–32), and Luke (23:26–32) describe the event, Luke providing the most detailed account. All three mention that a bystander from the vicinity, Simon of Cyrene, was engaged to assist Christ with the heavy burden of the cross (Matthew 27:32, Mark 15:21–22, Luke 23:26). Simon is the man dressed in green with red leggings seen lifting the cross at its center. The biblical narratives were augmented by other textual sources that embellished the story, elaborating on the protagonists present and the emotional tenor of the event. Among these are the Pseudo-Bonaventure’s

Meditations on the Life of Christ (Meditationes Vitae Christi) of around 1300 and the

Life of Christ (Vita Christi) completed in 1374 by Ludolf of Saxony.[1] The former mentions a key episode shown in the foreground of The Met’s painting when Christ paused upon his arduous route and a woman named Veronica (derived from the Latin

Vera Icon, meaning True Image) wiped the blood and sweat from his face, thus creating a miraculous image of Christ’s countenance on her cloth. Both Pseudo-Bonaventure and Ludolf of Saxony relate in dramatic detail how distraught the Virgin Mary, John the Evangelist and three other Marys were when they encountered Christ stumbling beneath the cross.[2] They can be seen pausing half-way up the steep path at the center of the painting, weeping uncontrollably. The Met’s painting departs from most depictions of the theme by showing the two thieves to be crucified with Christ not walking together but separated as they are coerced by the guards along the path at the left. The upper left corner of the painting shows preparations for the crucifixions of the three men, as the crosses are raised and secured in the ground.

Among those wending their way to Golgotha are Jewish men, identified by their pointed hats and red and yellow attire. New Testament texts (Matthew 27:16, Mark 15:7, Luke 23:19, John 18:40) identify the Jews as responsible for condemning Christ to the cross. When asked by Pontius Pilate whether the prisoner Barabbas or Christ should be pardoned, they chose Barabbas. Notable as well is the group emerging from the city gate at the right that includes a cuirassed centurion on horseback in a gold pointed hat and carrying a gold reliquary on a staff; a man dressed in a red fur-lined gown and fur-trimmed hat, attended by two pageboys; and various other well-appointed citizens following on horseback behind them.

The costumes of several of the figures are decorated with partially readable texts on the borders of their garments. Pierre Sosson first attempted a transcription of the phrases on the costume of the man in red whose back is turned to us at the far left, reading: EL BEEF GHELOVTE E. P. OMAGAME SALIAT EEN SC. DAET SAT DI BLOET M... (Urbach 1991, fig. 1). The words

omagame (procession) and

bloet (blood)—clearly visible along the right edge of the right sleeve, and at the shoulder of the left sleeve—suggested to Urbach (1991) and Ainsworth (1998) the cult of the Holy Blood in Bruges, and the yearly procession held since 1281 in which the city’s most important relic, that of Christ’s blood, is featured. Popular legend claimed that the vial of blood was brought to Bruges after the Second Crusade of CE 1147–49, by Thierry, Count of Flanders, who returned from Jerusalem with the relic presented to him by his brother-in-law Baldwin III of Jerusalem, as a reward for his bravery. The Confraternity of the Holy Blood was founded in 1405 and comprised a group of twenty-six elite male members of society, expanded in 1471 to thirty-one (Trowbridge 2009). The cuirassed centurion on the white horse at the lower right brandishes a staff surmounted by a gilded container topped with a pelican pricking its breast to feed its young—symbolic of Christ who suffered and died for humankind. Might this have been one of the processional reliquaries created to house the Holy Blood? Mark Trowbridge’s extensive research concerning the Confraternity of the Holy Blood has discovered archival documents confirming that the group owned “a staff with a pelican” and referring to “ons roedragher”—a staff bearer, who was a clerk of the confraternity. This man carried the staff during masses and probably for the Holy Blood procession (Trowbridge 2009, p. 5). According to Don La Rocca (Curator Emeritus of The Met’s Arms and Armor Department), the man’s armor is not based on existing models, but rather is intended to evoke something from foreign lands of an earlier time (La Rocca 2022). The inscription on the armor can be partially transcribed: [II] V I D [or n] A G A S P [r or I’] D E II [or N] C [or E] L (Trowbridge 2009, p. 5; fig. 2). However, it cannot be easily deciphered as either Latin or Flemish, and any hope of identifying the name “Gasp[a]r Den Cel” with Confraternity members of the late fifteenth-century has not met with success. However, there is also another figure present who suggests a connection with the confraternity. This is the armored horseman farther back near the city gate, who carries a crossbow and wears a red hat and a reddish-brown cloak with an embroidered insignia that appears to include birds’ wings or leafy branches (fig. 3). As noted by Trowbridge (2009, p. 6), such a garment recalls the tabard worn by the provost of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, as it is illustrated in the group’s

Parure Boeck (housed in the Archief van de Broederschap van het Heilig Bloed, Bruges). In addition, payments for the red hood worn by the provost are found in the account books. Apparently, a new red hood was worn each year, and the design of the tabard also changed from provost to provost. Therefore, what is represented in the painting is more likely a reference to various designs than to a specific one of a given time.

The Attribution and Date: Early in the literature concerning this painting, its attribution was linked to North-Netherlandish artists such as Aelbert van Ouwater and Gerard David, while the latter was still in Haarlem, before he resettled in Bruges in 1484 (Grisebach 1912; Zimmermann 1917; von Baldass 1920–21; Garas 1954). Others noted the connection with works by Jan van Eyck and considered The Met panel as a free copy after an Eyckian original—

Christ Carrying the Cross—known only as a replica in the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest (Winkler 1916; Hoogewerff 1936; Schone 1937; Weale and Salinger 1947; Meiss 1956; Larsen 1960; Carter 1962; Faggin 1968; Urbach 2015) or related to the Turin-Milan Hours (Baldass 1952; Panofsky 1953). Diane Scillia (1975), on the other hand, proposed an artist in the workshop of the Utrecht Master Evert Zoudenbalch ca. 1475.[3] She noted the synthesis of painting styles of Eyckian origin, especially the composition, with figure types, narrative details, and garish colors typical of the miniaturists of Utrecht. As Maurits Smeyers and Bert Cardon (1991) pointed out, however, there was a fluid artistic exchange between Utrecht and Bruges in the fifteenth century and there are numerous examples of Eyckian and Bruges-origin motifs in Utrecht compositions.[4] Considering another influence, Stephan Kemperdick (1997) compared The Met painting to the Master of Flémalle’s

Betrothal of the Virgin (Museo del Prado, Madrid) for its exoticized heads, Latin [sic] inscriptions, abrupt perspectival leaps, and particularly for the Saint Veronica figure in the foreground with the wreath-like headdress and long hair braid.

What is inescapable is the connection of The Met’s painting to the composition by Hubert or Jan van Eyck, the

Christ Carrying the Cross of about 1422–25, reflected in the early sixteenth-century copy in Budapest (Winkler 1916; Pigler 1968, p. 214; Rotterdam 2012–13; Urbach 2015; fig. 4). The Budapest copy is a horizontal format, while New York painting is a vertically-oriented composition. The latter took into account other Eyckian compositions that show a procession wending its way in U-shaped fashion from one side of the painting to the other. The

Way to Calvary by Hand K or the

Arrest of Christ by Hand G, both from the destroyed section of the Turin-Milan Hours, from around the 1440s or 1450s and 1420s or 1440s respectively, are such examples (figs. 5, 6). The composition as well as the rhythm and flow of the procession in the

Way to Calvary is especially comparable to The Met’s painting when the orientation of the former is reversed. The

Arrest of Christ provides a model for the wispy clouds, the Flemish town, including the Jerusalem temple, in the far distance, and the high horizon line of The Met’s painting.

Specific details of The Met’s painting appear to be assimilated from the Eyckian

Christ Carrying the Cross in Budapest. Most notable is the walled-in Flemish town with regularly placed towers between crenellated walls that extend from the city gate at the far right (fig. 7). Placed prominently within this town, and representing the holy city of Jerusalem, is an approximation of Herod’s third Temple of Solomon. It references the Dome of the Rock with the addition of flying Gothic buttresses. The group of men on horseback riding out through the city gate behind Christ is based on the Eyckian composition (fig. 8), as is the group of figures heading up the steep hill with the two thieves and the onlookers at the lower left (fig. 9). In each case, certain figures are copied almost exactly, even if select ones are moved in position. These various figural motifs are found not only in the Budapest copy of the van Eyck painting, but also in a surviving silverpoint drawing from the Circle of Van Eyck, namely the

Cavalcade of about 1450 (from

Christ Carrying the Cross, Herzog-Anton-Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, fig. 10).

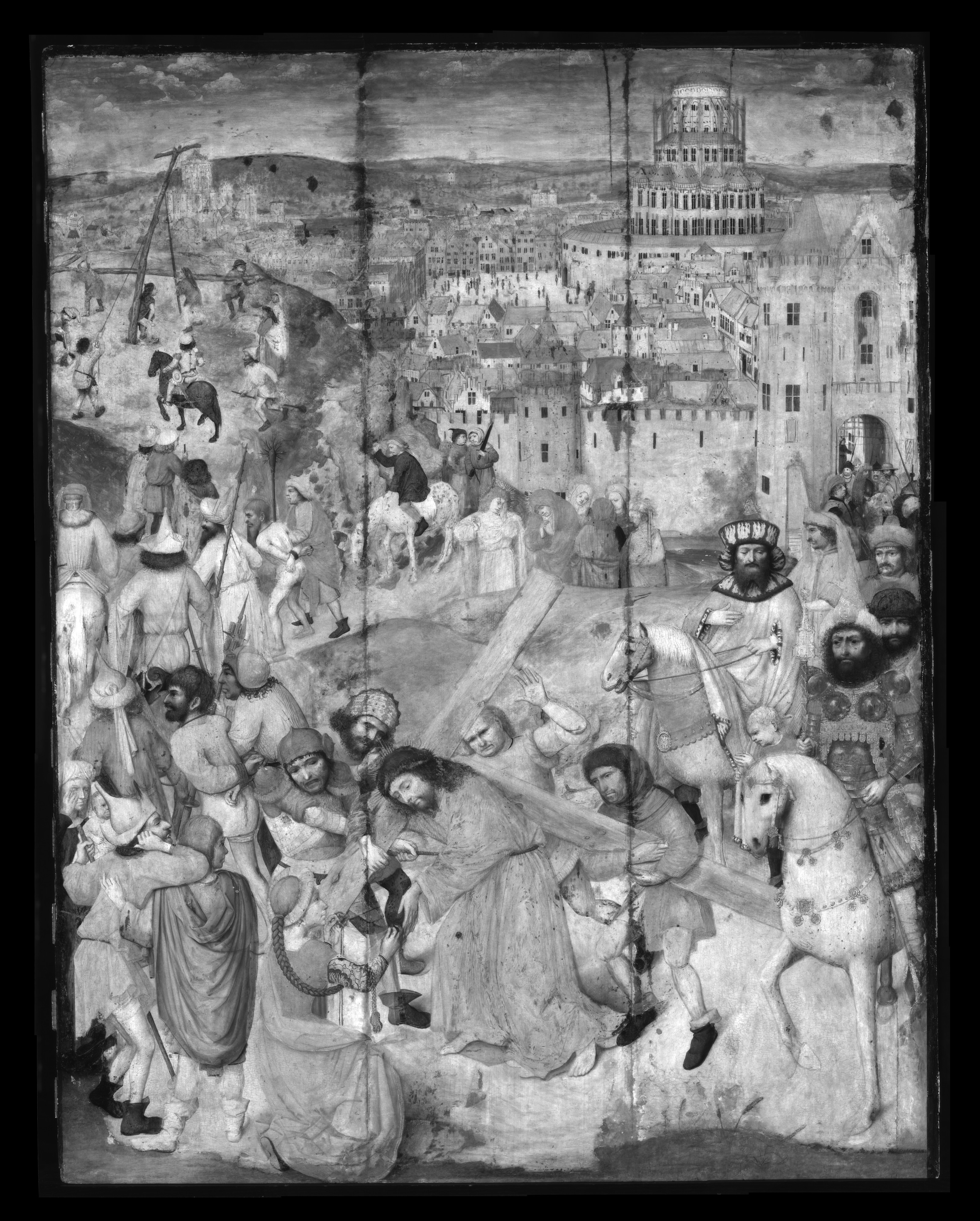

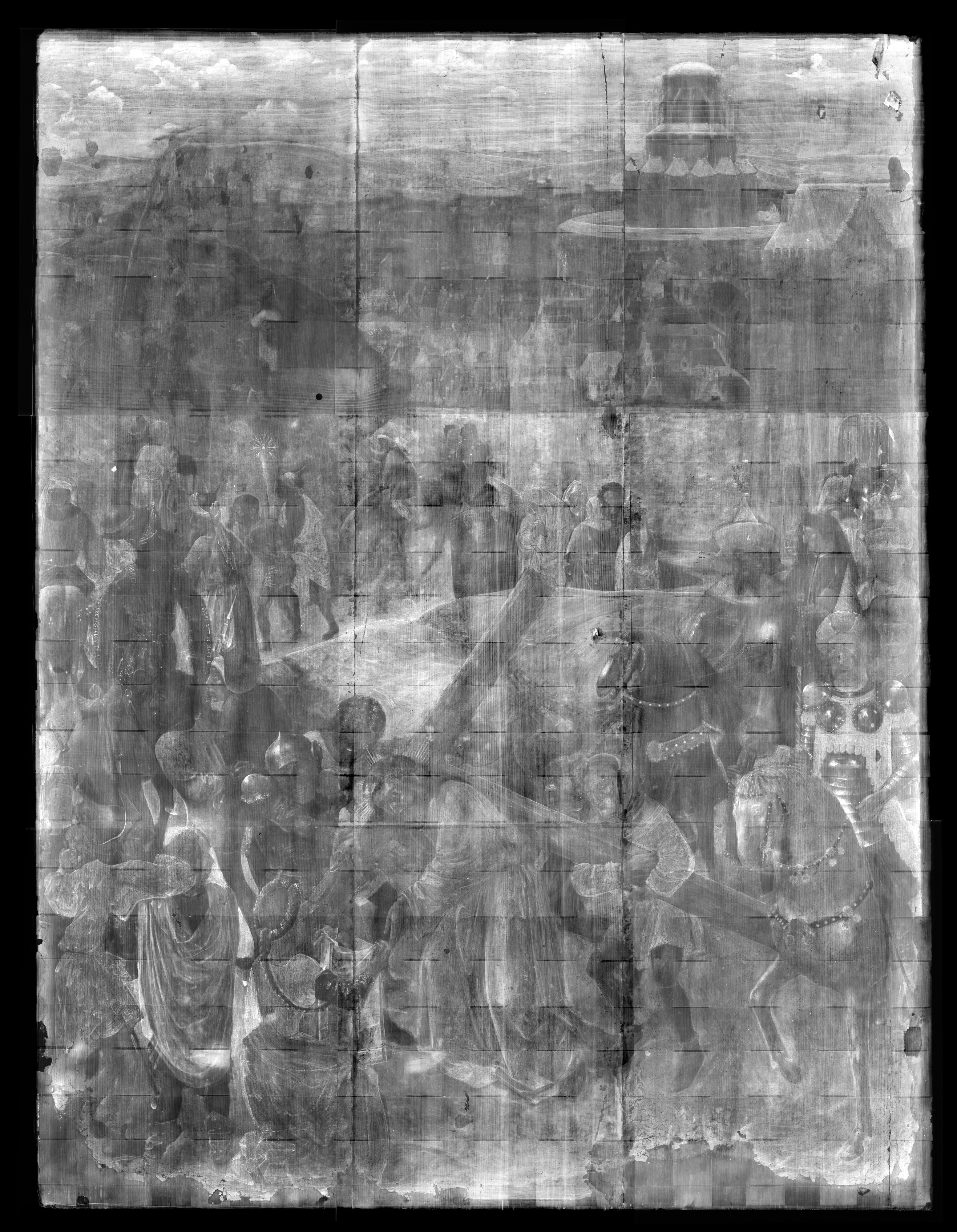

The artist of The Met’s painting was quite familiar with the Eyckian composition and seamlessly integrated various motifs into his own reworking of the theme. While a drawing on paper was likely the guiding model for the rather complex composition, The Met’s painting shows an extremely fully worked up preparatory sketch in a liquid medium on the ground of the panel that prepared not only the composition but a detailed rendering of the figures. The underdrawing features very fine parallel hatching and short curved strokes for the modeling of the draperies of the figures and an extremely detailed rendering of the architecture of the walled-in city (fig. 11). Such a meticulous preparatory sketch may have served as a

vidimus produced for the approval of the patron before the painting could proceed. There are numerous adjustments from the underdrawing to the final painted stage, most of them minor in nature, except for an additional figure at the base of Golgotha which was painted out (see Technical Notes).

The condition of the painting makes quality judgments concerning the figures somewhat difficult. Nonetheless, it appears that more than one painter worked on this rather large panel. The detailed characterization of some of the male heads, which appear almost portraitlike within the group emanating from the city gate, and the beautiful rendering and tender expression of Christ’s physiognomy depart rather dramatically from the secondary figures, some of which are far more caricature-like and others even blandly depicted (see Technical Notes for further remarks on the differences in painting technique). It is likely that this painting was a workshop effort of more than one hand. This master may well have come from the North Netherlands, as Diane Scillia, proposed, and was certainly aware of Eyckian manuscript illumination. However, the detailed nature of the presentation that indicates specialized knowledge of Bruges and its Confraternity of the Holy Blood points to an artist working in that city around 1470.

Especially revealing in terms of where The Met’s painting was made is its specific connections with the activities of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, particularly with the almost yearly processions in honor of the relic and the

tableaux vivants that often accompanied the procession (Trowbridge 2009, pp. 6–9). As such, the painting commemorates for the unknown person or group who commissioned it the yearly processions celebrating Bruges’ most renowned relic of the Holy Blood. The panel is large (42 3/8 x 32 3/8 in., or 107.6 x 82.2 cm) and unlikely to have adorned the walls of a private house. Rather, its size and particular reference to the Confraternity of the Holy Blood and its annual processions suggest a placement perhaps in the meeting rooms of the confraternity or in a chapel associated with that group. That the panel was originally in a public or semi-public location in Bruges is supported by the fact that Gerard David’s

Christ Carrying the Cross of about 1510 (

1975.1.119A–B) appears to reference the central group of Christ, Simon of Cyrene, and two of the soldiers who beat Christ as he trudges forward under the weight of the cross. Based on the dendrochronology of the panel by Peter Klein, the painting could have been produced anytime from 1463 onwards (see Technical Notes).

Maryan Ainsworth 2022

[1]

Meditations on the Life of Christ, trans. By I. Ragusa and R. B. Green (Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology, XXXV), Princeton, J., 1961, pp. 330-32, ch. LXXVII; Ludolphus de Saxonia,

Vita Jesu Christi, d. by L. M. Rigollot, Paris and Brussels, [1865], pp. 646–50.

[2] Ragusa and Green 1961, pp. 331–32 (for the Pseudo-Bonaventure); for Ludolphus de Saxonia, see Rigollot 1878, IV, p. 88, par. 3.

[3] On the Master of Evert Zoudenbalch, see

The Golden Age of Dutch Manuscript Painting, exh. cat. Pierpont Morgan Library (March 1–May 6,1990), Braziller, New York, pp. 198–211, nos. 61–65.

[4] Maurits Smeyers and Bert Cardon, “Utrecht and Bruges—South and North ‘Boundless’ Relations in the 15th Century,” in Koert van der Horst and Johann-Christian Klamt, eds.,

Masters and Miniatures, Proceedings of the Congress on Medieval Manuscript Illumination in the Northern Netherlands (Utrecht, December 10–13, 1989), Doornspijk, 1991, pp. 96–99.