The Artist: For a biography of Murillo, see the Catalogue Entry for

Virgin and Child (

43.13).

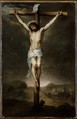

The Painting: Against a dark sky and dramatically setting sun, Christ’s twisted muscles are pulled between the bars of the cross, his skin aglow in moonlight. The atmospheric landscape follows the Gospels (notably Mark 15:33 and Matthew 27:35) which relay that as Christ’s earthly body fell limp on the cross, “darkness came over all the earth.” Lightly sketched in domes and towers in the distance evoke the skyline of Jerusalem.

Murillo’s evocative lighting derived from scripture as well as artistic precedents that treated the Crucifixion against dramatic evening skies, notably compositions by Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641; see, for example, fig. 1 above) and Murillo’s fellow Sevillian, Alonso Cano (1601–1667; fig. 2). Murillo’s characteristic technique of softly blending his paint was perfectly suited to such brooding effects. In his positioning of Christ’s body, Murillo has abandoned the advice of Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644) in

Arte de la pintura (1649) that the most orthodox depiction of Christ crucified was with four nails, his feet placed side-by-side as Pacheco’s student and son-in-law, Diego Velázquez, had depicted the scene early in his career (1632; Museo del Prado).[1] As the precedents by van Dyck and Cano suggest, however, many artists found the use of three nails to be a more elegant solution that allowed for a contortion of the body into a kind of suspended contrapposto.

The purpose of The Met’s painting, executed relatively quickly and at a small scale, has been the subject of much debate. Clearly, it is closely related to Murillo’s large-scale

Christ on the Cross (fig. 3), generally dated about 1675 and originating in the Spanish royal collections. In The Met’s version, details of the inscription above Christ’s head and the scull synonymous with Golgotha or Calvary (which, respectively, come from Aramaic and Latin for “scull”) are absent, presumably due to limitations of size, but the lighting and overall conception is nearly identical. The key question revolves around whether The Met’s painting was a preliminary sketch anticipating the Prado’s larger work, or a reduction intended as an independent painting for private devotion. In Jonathon Brown’s pioneering study of Murillo’s oil sketches, he classified this painting as “a study for a painting in the Prado,” while Peter Cherry’s recent reexamination of Murillo’s oil sketches classifies it as an autograph reduction or, at least, an independent work.[2]

Cherry’s reasoning for classifying the painting as an independent painting, rather than preliminary sketch, stems from an in-depth analysis of early terminology for Murillo’s oil sketches and comparison of finish in the artist’s small-scale works, ranging from the quite rough, broad paint application of what he considered undoubtedly sketches (for example, the Wallace Collection’s

Virgin and Child in Glory, ca.1665–70; fig. 4) versus higher degrees of finish, such as that found in The Met’s painting. This greater resolution, Cherry suggests, might play on the aesthetics of the oil sketch that appealed to amateurs, but they were not, as previously assumed, stages in producing large-scale commissions. He admits to the difficulties of assigning any clear taxonomy to Murillo’s small-scale paintings, noting that the artist’s after-death inventory makes no mention at all of preparatory works (presumably they were simply part of the “todo el estudio de pintura” valued at 600 reales) and inconsistences of terminology are found throughout the inventory of his son and heir, Gaspar Esteban. Cherry notes that the period term for what we would call oil sketches was

barrones, which indicated a rough draft in color, usually destined for working up at a larger scale.[3] The early seventeenth-century painter and art theorist Vincente Carducho (ca. 1576–1638) described such color oil sketches as a stage of artistic development that came after the composition had been worked out on in graphite or ink on paper, noting that painters “make colored blots [

borroncillos] that are the whole concept” (

Tambien se hacen borroncillos de colores, que es todo el concepto); in his

El museo pictórico y la escala óptica (1724), Antonio Palomino (1655–1726) listed borroncillos among the items that one might show to a trusted friend when seeking advice on the development of an artistic idea.[4]

When compared with works such as the Wallace Collection’s

Virgin and Child in Glory, The Met’s painting, indeed, evidences a much higher finish—its level of resolution is arguably as close to the Meadows Museum’s oil on copper

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin, Mary Magdalene and Saint John of about 1670 as it is to the works Cherry discusses. Whether or not it came before or after the Prado’s far larger version, however, the question of its authorship seems settled. The level of painterly finesse and expression via Christ’s contorted musculature are wholly in keeping with Murillo’s own brush rather than that of a copyist or assistant in his workshop. Marcus Burke has noted, in fact, that the expressive distortions of the arms and legs that are very successful and expressive on a small scale lose their effectiveness in the Prado version. He posits that workshop assistance might have been used for the larger work, noting that The Met’s painting shows a particular mastery of light and form in the twisted torso and the space between Christ’s legs.[5]

This painting is possibly the same that Edward Davies reported in 1819 as “un crucifixo en pequeño” and formerly in the collection Sebastián Martínez y Pérez (1747–1800).[6] As indicated by Goya’s portrait of Martínez holding a print (The Met,

06.289), he was an important collector of paintings, books and works on paper.

David Pullins 2020

[1] Brown 1978, p. 71; Stratton-Pruitt 2002, p. 128.

[2] Brown 1976, p. 189; Cherry 2019, p. 221.

[3] Vicente Carducho,

Diálogos de la Pintura: su defensa, origen, esencia, definición, modos y diferencias (1633; republished by Turner, Madrid, ed. by Francisco Calvo Serraller, 1979), p. 385; Cherry 2019, pp. 223, 225.

[4] Palomio 1724, II, p. 375; Cherry 2019, pp. 221–22.

[5] Burke 1979, p. 68.

[6] Davies ed. 1819, pp. xciv; Stratton-Pruitt 2002, p. 171.