The Artist: For a biography of Adriaen Isenbrant, see the Catalogue Entry for

Man Weighing Gold (

32.100.36).

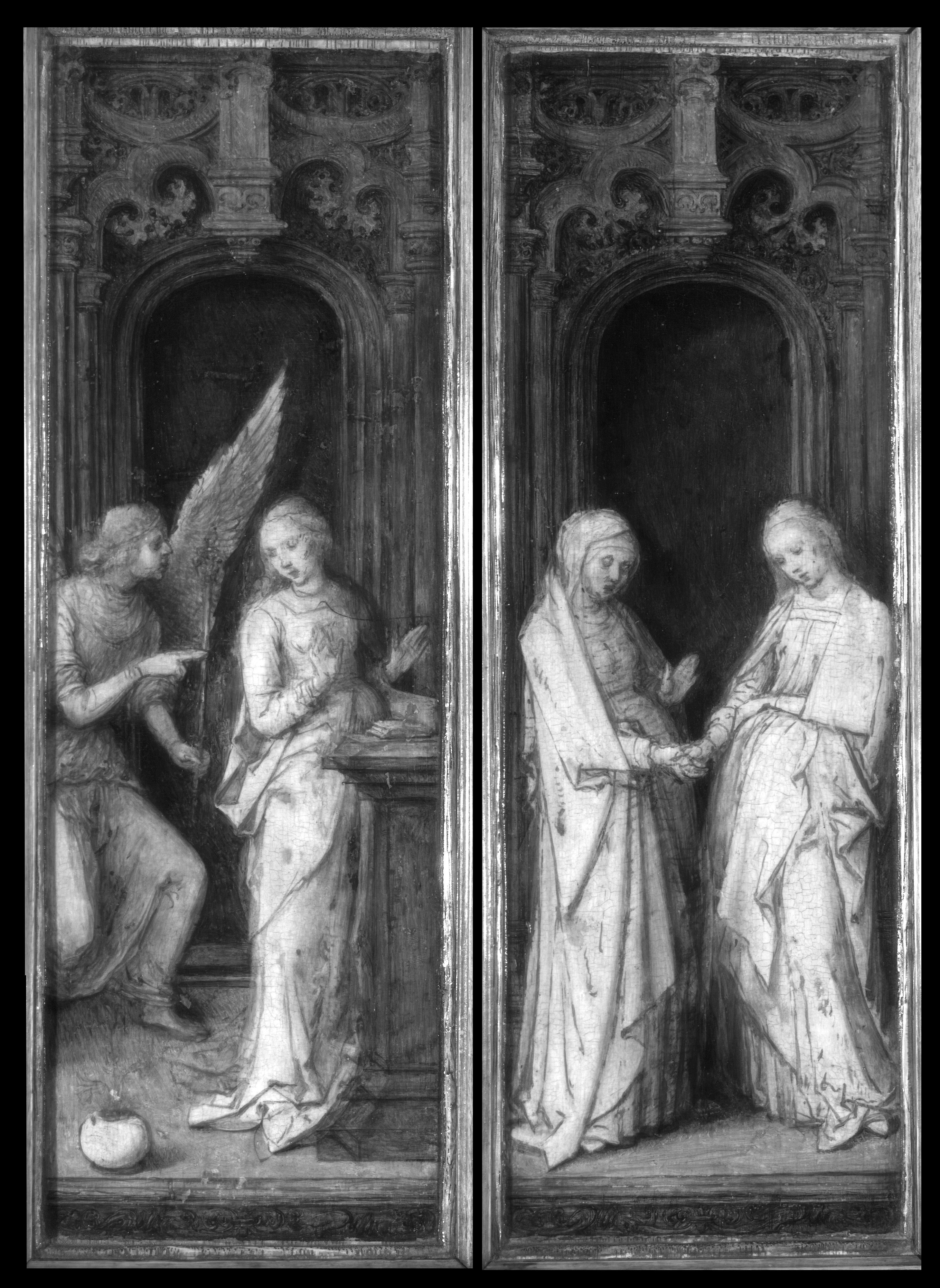

The Subject of the Painting: This triptych shows scenes from the Life of the Virgin, a very popular subject with a rich artistic tradition. All the scenes in the triptych are borrowed from compositions of different artists. The grisaille Annunciation on the left exterior wing, next to the Visitation on the right, was directly inspired by the same subject in the

Life of the Virgin woodcut series by Albrecht Dürer, published in 1511 (The Met,

18.65.16). For the interior, the artist sought inspiration from Gerard David. The central panel with the Nativity was most likely based on the composition of David’s

Nativity with Donors and Saint Jerome and Leonard (

49.7.20a–c). The left wing depicting the Adoration of the Magi calls to mind David’s

Adoration of the Magi of about 1490 (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels). The Flight into Egypt on the right wing was inspired by Dürer’s

Life of the Virgin series, using the

Flight into Egypt print (

57.531.9) as an example for the painting. This was an especially beloved theme and one that Isenbrant repeated in one of the medallions on the left wing of

Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows (Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels). He also repeated the triptych’s Nativity scene various times in other works that can be found in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh in Antwerp, the Kunstmuseum Basel, and National Gallery of Art, Washington (see Hand 1986, pp. 118–22, and fig. 1 above). The painting in Washington shows greater maturity in style, but shares a specific detail with The Met’s triptych, namely the basket on which the naked Christ Child (

corpus verum) is lying. This substitute altar alludes to the sacrament of the Eucharist (see Sintobin 1998, p. 372). Another similarity to the Washington panel is the Italianate architecture, decorated with then-new, fashionable motifs, such as gilded capitals with acanthus leaves and grotesques on top of the marble columns, seen at the left and central panels of the triptych. These architectural elements, together with the elaborate grisaille canopies on the outer wings, were influenced by the style of the Antwerp Mannerists, and give the more traditional compositions a modern sensibility. The interior of the triptych shows a continuous landscape reminiscent of Gerard David and Joachim Patinir, with its wide, sweeping view, filled with small details. Also sometimes occurring in the sixteenth century are wings that are taller than the central panel (see Sintobin 1998, p. 373).

The Function of the Painting: The small and portable triptych is an excellent example of art intended for private devotion. By portraying the tribulations that the Virgin and her infant son endured, the artist intended to evoke the viewer’s empathy. This was common practice in the Modern Devotion, a religious movement that began in the fourteenth century and lasted until the Protestant Reformation. It encouraged individual meditation on and contemplation of the suffering of Christ and the Virgin (for more information on the Modern Devotion, see

"Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.). Because of its small size, the triptych could easily have been transported by its owner on his or her travels. Perhaps it belonged to an individual of the wealthier middle class who used this triptych for daily devotions in private chambers. Or, in the words of Sir Martin Conway, "Such a little altarpiece was perfectly adapted for the oratory of some young and pious but also well-to-do lady of its day" (see Conway 1921, p. 303).

The Attribution and Date: Attribution is problematic in Isenbrant’s oeuvre, as Jean Wilson (1995) has pointed out. Among the five hundred works in his oeuvre, not a single one can be ascribed to Isenbrant with certainty. Stylistically, the triptych is more on the traditional side. Isenbrant depends heavily on the style of Gerard David, and although Isenbrant’s landscapes are similarly detailed, his frontal figures have a softer and almost hazy quality to them (see Technical Notes). Another distinguishing feature of this triptych is the overall warmer color palette, especially in the reds and browns, which Isenbrant tended to favor. This may have been why a number of Isenbrant’s works, including The Met's triptych, were first attributed to Jan Mostaert and his followers, as "red is the ruling color in the pseudo-Mostaert group" (see Friedländer 1899, p. 15).

It is useful to compare the triptych with other works, such as the Washington panel (fig. 1) or

The Flight into Egypt, sold at Sotheby’s, New York, May 22, 2018, no. 19 (see Sotheby's 2018). Both of these works show the same stylistic characteristics mentioned earlier concerning the triptych. Infrared reflectography provides additional material for comparison (figs. 2, 3; for a detailed description of the triptych’s underdrawing, see Technical Notes). Since the published IRR of the Washington panel only shows the bottom half of the painting (see Hand 1986, p. 120), any comparison must be limited to the figures and draperies. It should be noted that in both paintings the underdrawing is difficult to distinguish, since it often seems to have been followed with painted black contours. In places where the underdrawing has not been followed in paint, and therefore is visible (for the triptych’s underdrawing, see Technical Notes), the two examples appear comparable, especially in their handling: bolder strokes in the draperies, as opposed to the faint, more carefully drawn lines in the faces. The underdrawing of the landscape on the interior of the triptych, however, consists of loose sketchy strokes in a dry medium that give only a general impression of where the mountains, trees, and houses should be painted. This is similar to the Sotheby’s

Flight into Egypt, with the slight discrepancy that this underdrawing shows more hatching in the foreground of the landscape, indicating the shaded areas, than in The Met's triptych (see Sotheby's 2018, p. 46).

Compared to the Sotheby’s

Flight into Egypt and the Washington panel, The Met’s triptych seems to have originated earlier. Véronique Sintobin dates the painting after 1521, the year Albrecht Dürer visited the Netherlands and gifted an entire set of his woodcut prints to Margaret of Austria, although the prints probably already circulated in Bruges before that date (see Sintobin 1998, p. 372). Given the reliance on Gerard David’s (ca. 1455–1523) compositions and style, which lasted Isenbrant’s entire career but was especially prevalent in the first two decades, Sintobin’s suggestion of a date around 1521 seems most reasonable. Unfortunately, concerning the question of authorship, the best that can be done for now is to compare the various paintings attributed to Isesnbrant. Until a document or signature surfaces that can link a work securely to Isenbrant, the attribution of the

The Life of the Virgin must remain open. However, this endearing triptych exhibits many of the qualities, stylistically and otherwise, often associated with Isenbrant and his workshop.

Joyce Klein Koerkamp 2019