The Artist: Jan Sanders van Hemessen was one of the most important painters in Antwerp between Quinten Massys and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In the first half of the sixteenth century, Antwerp emerged as an international center for commerce and art-making, with a nascent open market for luxury goods and works of art. Van Hemessen pioneered novel subjects and compositions for the burgeoning Antwerp art market. His satirical stand-alone genre paintings portray bawdy scenes devoid of explicit religious content. He likewise developed hybrid religious works which, while ultimately portraying Gospel subjects, foreground profane motifs characteristic of genre scenes, thus requiring a careful viewer to discern the full devotional function.

Van Hemessen’s significant contribution to the development of new subjects and pictorial forms for the Antwerp art market is further distinguished by his consistent focus on large-scale, muscular bodies. His figures reflect a deep engagement with classicizing artistic models from both north and south of the Alps, ranging from Raphael to Jan Gossart. Following Quinten Massys (see

The Adoration of the Magi,

11.143), Van Hemessen frequently utilized a half-length portrait format to place viewers in direct contact with nearly life-sized figures—including figures with stereotyped physiognomies designed to exemplify beauty or ugliness, derived from Leonardo da Vinci. Van Hemessen likewise transformed quotations from fifteenth-century Netherlandish painters already revered as “old masters” by the early sixteenth century. His artistic approach particularly influenced Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer (see

Fish Market,

2015.146), who continued the development of genre and hybrid imagery for the Antwerp art market. Catharina van Hemessen, Van Hemessen’s daughter, was an accomplished painter in her own right, and may have participated in the workshop.

The many workshop versions and copies after Van Hemessen originals attest to the success and popularity of his designs. The high regard for his paintings into the seventeenth century is further suggested by their presence in major seventeenth-century royal collections: seven paintings were in the collection of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II; a

Calling of Saint Matthew of about 1540 was owned by Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria; and a major genre painting, the

Stone of Folly, was part of the collection of the Spanish Habsburgs.[1] Van Hemessen was mentioned by Lodovico Guicciardini (1567), Giorgio Vasari (1568), and Karel van Mander (1604).[2] It is interesting to note that in 1610 the Jesuit writer Carolus Scribani, in his praise of Van Hemessen as an illustrious Antwerp painter, claimed that the bagpiper in the 1536

Prodigal Son was actually a self-portrait.[3] This interpretation, while not necessarily accurate, attests to the early reception of Van Hemessen’s work as playfully self-aware.

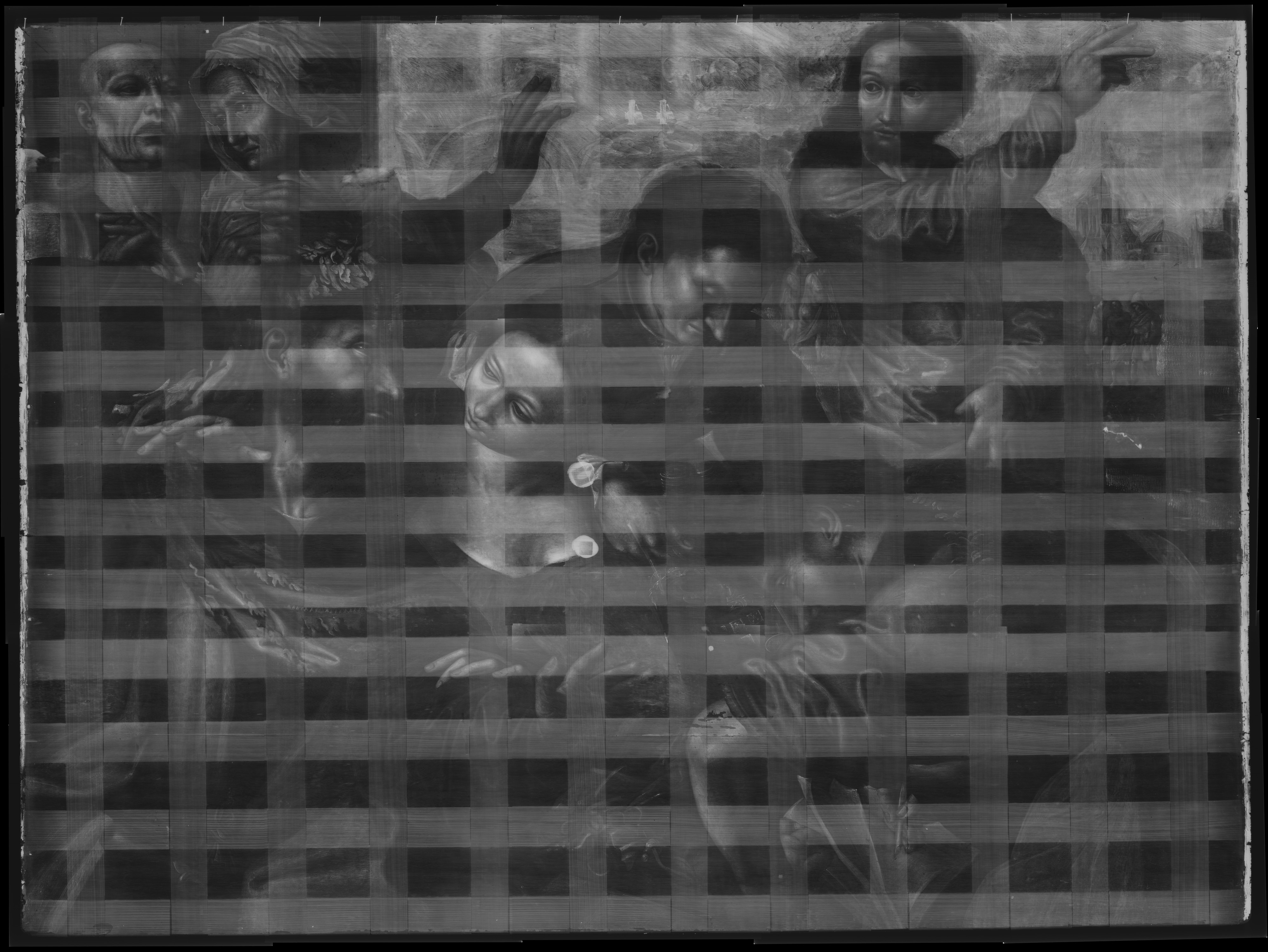

The Subject of the Painting and its Function: The

Calling of Saint Matthew of about 1548 by Van Hemessen (original in Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; see fig. 1 above) reimagines the pithy Gospel account of Matthew’s conversion, told in Matthew 9:9, as a busy and disorienting scene. At upper right, Christ calls Matthew to leave his life as a tax collector and become a disciple. Yet Matthew, at lower left, hesitates. A beautiful young woman encircles Matthew and seeks to restrain him, and his fellow tax collectors ignore Christ. They remain bent over their work at a table filled with the tools of the tax office, from shiny stacks of coins to a full money purse. The painting showcases Van Hemessen’s characteristically inventive recombining of a range of artistic models, notably the flamboyant headgear of Matthew. This headgear references and exaggerates Burgundian courtly costume from a hundred years earlier, as seen in paintings by fifteenth-century Netherlandish masters such as Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

The subject of the Calling of Saint Matthew did not exist in Netherlandish painting before Van Hemessen and his peers undertook it. Genre subjects of money changers and tax collectors preceded portrayals of the Gospel story.[4] Quinten Massys’s

Money Changer and His Wife from 1514 (Musé du Louvre, Paris; fig. 2) provides a clear model for the subsequent Calling images developed in the 1530s by Van Hemessen, Marinus van Reymerswaele, and Quinten’s son Jan Massys, including in the choice of outmoded dress for the main figures. An early painting of the subject by Van Hemessen, signed and dated 1536, was likely originally intended as a stand-alone genre scene of a tax collector’s office (Alte Pinakothek, Munich; fig. 3). The figure of Christ and the cartellino with an inscription identifying the Gospel story are both later additions.[5] A

Calling of Sainy Matthew of about 1540 by Van Hemessen (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; fig. 4) is more awkward than the version of about 1548, particularly when it comes to the foreshortening of the twisting torso of the young woman. However, Van Hemessen clearly developed the later painting out of his earlier design. The Vienna

Calling of about 1548 is the most sophisticated version of the subject, and is one of the most complex and exquisite works in the artist’s oeuvre.

This type of hybrid religious image emerged in a period when Antwerp remained an officially Catholic city, yet also when the circulation of Reformation ideas through sermons and printed materials was still unevenly censored by the ruling Habsburgs. Drawing a connection to the biblical humanism of Erasmus, Grace Vlam saw paintings of the Calling of Saint Matthew by Van Hemessen and his peers as “a call to the Reformation.” Burr Wallen saw Van Hemessen’s

Calling of about 1548 as a Catholic image—a product of the Counter-Reformation.[6] However, any reading of the artist’s body of work along lines of Catholic orthodoxy or of covert Protestant sympathies misses the more nuanced ways artists were engaging with Reformation ideas, especially the Protestant critique of traditional, iconic religious images. New hybrid religious images by Van Hemessen and his peers embed the essential details of the biblical narratives within intentionally complex and even misleading compositional structures, simulating the experience for original viewers of having to discern the sacred message within a distracting and corrupted profane world. The key to understanding the

Calling of about 1548 is that entirely different attitudes toward the religious message are being portrayed by figures that are pressed together in a small space despite how starkly their attitudes diverge.

The Attribution: The

Calling of Saint Matthew in The Met closely follows the composition of about 1548 in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. The Met painting has close to the same dimensions as the original, and the composition of the foreground figures is carefully followed in arrangement, scale, and details (see Technical Notes). The only major derivation from the composition of the original is the absence of the classicizing architecture in the background. Curiously, this architecture was initially planned and even executed before being painted out, possibly at a later date. The eight extant period copies of the Vienna

Calling of about 1548 demonstrate the popularity of Van Hemessen’s design.[7] The Met's version is one of the three highest quality copies, along with a likely workshop version in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (fig. 5) and a possible workshop version in the National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest (fig. 6).

The Met's version, while less nuanced than the original painting, is nevertheless an ambitious copy that sheds light on the original reception of Van Hemessen’s work. The faces of the figures are painted in passages with thicker, impasto brushwork uncharacteristic of Van Hemessen, thus situating it outside of the workshop. The fact that it may be an early seventeenth-century copy, based on dendrochronological analysis, indicates the ongoing appeal and relevance of the design (see Technical Notes). The artist’s detailed attempt to emulate the sumptuous costume of Matthew, especially the elaborate dagging (serration) of his antiquated headdress, the bulging muscles in his neck, and his characteristically frizzy beard (now somewhat abraded) provide further evidence that the copyist had access to the original. In the seventeenth century, the original was most likely displayed as part of a diverse artistic collection—with genre and mythological subjects placed alongside traditional religious themes—intended to show off the wealthy owner’s erudition.[8] It also suggests that this painter understood how the visual interest and originality of Van Hemessen’s painting arises not only from the intricate intertwining of the figures in exaggerated poses, but also from the almost ornamental surfaces of fabrics, hair, and musculature.

Anna-Claire Stinebring 2019

[1] See Burr Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen: An Antwerp Painter Between Reform and Counter-Reform, Ann Arbor, 1983, vol. 3, nos. 20 and 49.

[2] Lodovico Guicciardini,

Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi, Antwerp, 1567; Giorgio Vasari,

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, from the second edition of

Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori (1568), trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, New York, 1979), vol. 3, p. 2061; Karel van Mander,

The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the first edition of

Het Schilder-boeck (1603–4), trans. and ed. Hessel Miedema, Doornspijk, 1994–99, vol. 1, fol. 205r; vol. 2: fol. 250–52. See Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen, p. 9.

[3] Julius Held, “Carolus Scribanius’s Observations on Art in Antwerp,”

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 59 (1996), p. 189. Also discussed in Bret Rothstein, “Beer and Loafing in Antwerp,”

Art History 35, no. 5 (2012), p. 900; Matthias Ubl, “Van hoerenhuis tot hoofse liefde: Jan Sanders van Hemessen, de Meester van de Vrouwelijke Halffiguren en Ambrosius Benson,” in

De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven: van Bosch tot Bruegel, ed. Peter van der Coelen et al., Rotterdam, 2015 p. 157.

[4] Larry Silver,

Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Rise of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market, Philadelphia, 2006, pp. 74–86; Grace A. H. Vlam, “The Calling of Saint Matthew in Sixteenth-Century Flemish Painting,”

The Art Bulletin 59, no. 4 (1977), p. 561.

[5] The cartellino reads “SE QVERE ME./MATTHAEI CAP:IX (Follow me/Matthew chapter 9).” Two early copies confirm that the original composition excluded the elements that clearly identify the Gospel narrative. See Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen, no. 16.

[6] Vlam, “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” p. 563; Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen, pp. 76–77. For a more nuanced discussion of the

Calling of about 1540, see Todd M. Richardson, “Early Modern Hands: Gesture in the Work of Jan van Hemessen,” in

Imago Exegetica: Visual Images as Exegetical Instruments, 1400–1700, eds. Walter S. Melion, James Clifton, and Michel Weemans, Leiden, 2014, pp. 294–319. Richardson does not analyze the later

Calling of about 1548.

[7] As recorded in The Met and KHM object files, building on Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen, no. 33, which lists five copies.

[8] A painting of about 1630–35 by Frans Francken II, the

Interior of Nicolaas Rockox’s House, portrays the collection of the powerful Antwerp Rockox family in one lavish room (Alte Pinakothek, Munich). Along with a contemporary painting by Peter Paul Rubens, an early sixteenth-century Netherlandish genre painting of a tax collector and his wife, and a Saint Jerome by Van Hemessen or his workshop (workshop version in the current collection of the Snijders & Rockoxhuis, Antwerp) are prominently displayed. See Zirka Filipczak,

Picturing Art in Antwerp 1550–1700, Princeton, 1987, pp. 58–72, esp. pp. 58–59. Both the Munich

Tax Collectors by Van Hemessen and the

Calling of Saint Matthew of about 1640 by Van Hemessen were part of grand royal collections in the seventeenth century: the collection of the Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria and the collection of the Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, respectively. See Wallen,

Jan van Hemessen, vol. 3, nos. 16 and 20.