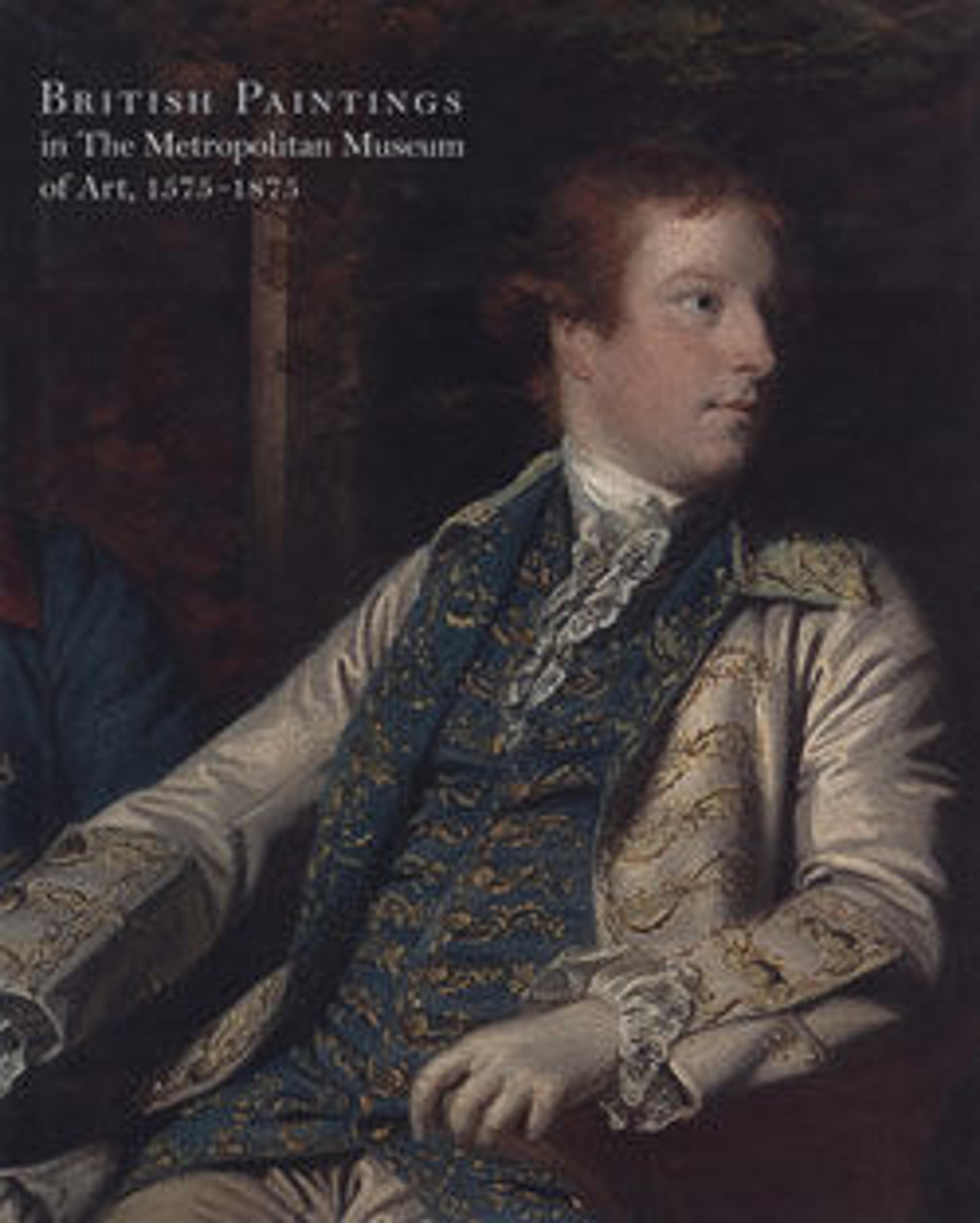

Portrait of a Woman

The wealth and elevated social status of this Elizabethan woman is suggested by her elaborate dress and jewels. Reflecting the influence of paintings by Nicholas Hilliard, this portrait and another of the same sitter at Parham Park in Sussex may be dated about 1600.

Artwork Details

- Title: Portrait of a Woman

- Artist: British Painter (ca. 1600)

- Date: ca. 1600

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 44 1/2 x 34 3/4 in. (113 x 88.3 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911

- Object Number: 11.149.1

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.