Seated dog

Not on view

Versión en español más abajo.

A significant number of ceramic pieces from ancient western Mexico come from mortuary contexts known as “shaft tombs.” The time, labor, tools, and materials required to create these underground spaces (excavation of shafts, tunnels, and chambers, as well as the deposit of bodies and offerings) suggest that this form of entombment was reserved for only the most elite.

Among the funerary offerings, pieces made with clay, often of exceptional quality, stand out. The Comala style is one of the most recognized within the funerary ceramic art of ancient western Mexico. The effigies, plants, and animals that were modeled in clay are hollow and retain an extraordinary polish on their surfaces, in which reddish tones predominate. With these formal parameters, the canines were expressed through rounded volumes and edges in considerable dimensions, which are very close to their real references´ anatomy and natural attitudes. The modeling of the head of this specimen combines incisions and sgraffito that denote the eyes, nostrils, and snout. With his ears up, he seems to be in an alert attitude, paying attention to his surroundings.

One of the most difficult questions is related to interpreting the use and meaning of the mortuary ceramic figures that clearly portray dogs. Various authors propose that these are representations of a nahual (guardian spirit or animal companion) of the deceased. These ceramic quadrupeds have also been linked to the late pre-Hispanic custom, of the Central Altiplano, of killing the dog of the deceased, which was believed to transport the soul of its master across the river of the underworld to the place of a final rest in the other side. Some specialists propose that they are representatives of deities or supernatural beings. Let us remember that the god Xólotl, in the form of a dog, accompanied Quetzalcóatl, his brother, to the underworld to recover the bones of the dead.

With long legs and a slender body, this sculpture may refer to the breed known as the “Mexican hairless dog” or xoloitzcuintle, which appears frequently in archaeological contexts. In contemporary Mexico, this animal has joined the catalog of icons of pride and national identity.

María Olvido Moreno Guzmán, 2024

Further Reading

Blanco Padilla, Alicia, Bernardo Rodríguez Galicia, and Raúl Valadez Azúa. Estudio de los cánidos arqueológicos del México Prehispánico. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2009.

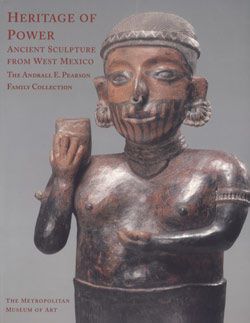

Butterwick, Kristi. Heritage of Power: Ancient Sculpture From West Mexico: The Andrall E. Pearson Family Collection. New York, New Haven, London: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Hernández Díaz, Verónica. “Muerte y vida en la cultura tumbas de tiro”, in Miradas renovadas al Occidente indígena de México, edited by Marie Areti Hers, p. 79. Mexico Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM, 2013.

Meighan, Clement W., and H.B. Nicholson. “The Ceramic Mortuary Offerings of Prehistoric West Mexico: An Archaeological Perspective.” In: Sculpture of Ancient West Mexico. Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima. A Catalogue of the Proctor Stafford Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Revised edition, by Michael Kan, Clement Meighan, and H. B. Nicholson, pp. 29-67. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989.

Pickering Robert B., Cheryl Smallwood-Roberts and Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art. West Mexico. Ritual and Identity. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, 2016.

Richard Townsend ed. Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1998.

Un número importante de las piezas cerámicas del antiguo Occidente de México procede de contextos mortuorios que se conocen como “tumbas de tiro”. El tiempo, la mano de obra, los implementos de trabajo y los materiales que se requirieron para conformar estos espacios subterráneos (excavación de tiros, túneles y cámaras, así como el depósito de los cuerpos y las ofrendas) sugiere que únicamente los miembros de clases sociales altas realizaban este tipo de prácticas. En los ajuares funerarios destacan las piezas elaboradas con barro, que con frecuencia presentan una calidad excepcional.

El estilo Comala es una de las manifestaciones plásticas más reconocidas dentro del arte cerámico funerario del antiguo Occidente de México. Las efigies, plantas y animales que se modelaron en barro, son huecas y conservan un pulimento extraordinario en sus superficies, en las que predominan las tonalidades rojizas. Con estos parámetros formales, los cánidos se plasmaron por medio de volúmenes y cantos redondeados en dimensiones considerables, que de buena manera se acercan a la anatomía y actitudes naturales de sus referentes reales. El modelado de la cabeza de este ejemplar combina incisiones y esgrafiados que denotan los ojos, las fosas nasales y el ocico; con las orejas paradas, pareciera que se encuentra en una actitud de alerta, poniendo atención a su entorno.

Una de las cuestiones más difíciles es la que se relaciona con la interpretación sobre el uso y significado de las figuras de cerámica mortuoria que retratan canes. Diversos autores proponen que se trata de representaciones de un nahual (espíritu guardián o compañero animal) del difunto. Estos cuadrúpedos de cerámica también se han vinculado con la tardía costumbre prehispánica, del Altiplano Central, de matar al perro del difunto, que se creía transportaría el alma de su amo a través del río del inframundo hasta el lugar de un descanso final en el otro lado. Algunos especialistas proponen que en realidad son representantes de deidades o de seres sobrenaturales; recordemos que el dios Xólotl, en forma de perro, acompañaba Quetzalcóatl, su hermano, al inframundo para recuperar los huesos de los muertos.

Con las patas largas y cuerpo esbelto, es posible que esta escultura refiera a la raza que se conoce como el “perro pelón mexicano” o xoloitzcuintle, que aparece con mayor frecuencia en contextos arqueológicos. En el México contemporáneo, este animal se ha sumado al catálogo de iconos del orgullo y la identidad nacional.

María Olvido Moreno Guzmán, 2024

Referencias

Blanco Padilla, Alicia, Bernardo Rodríguez Galicia, and Raúl Valadez Azúa. Estudio de los cánidos arqueológicos del México Prehispánico. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2009.

Butterwick, Kristi. Heritage of Power: Ancient Sculpture From West Mexico: The Andrall E. Pearson Family Collection. New York, New Haven, London: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Hernández Díaz, Verónica. “Muerte y vida en la cultura tumbas de tiro”, in Miradas renovadas al Occidente indígena de México, edited by Marie Areti Hers, p. 79. Mexico> Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM, 2013.

Meighan, Clement W., and H.B. Nicholson. “The Ceramic Mortuary Offerings of Prehistoric West Mexico: An Archaeological Perspective.” In: Sculpture of Ancient West Mexico. Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima. A Catalogue of the Proctor Stafford Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Revised edition, by Michael Kan, Clement Meighan, and H. B. Nicholson, pp. 29-67. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989.

Pickering Robert B., Cheryl Smallwood-Roberts and Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art. West Mexico. Ritual and Identity. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, 2016.

Richard Townsend ed. Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1998.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.