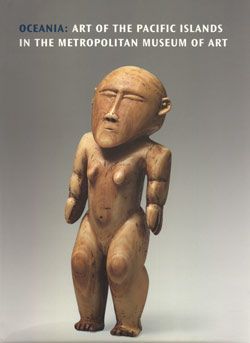

Sacred Figure (Luli dera)

Not on view

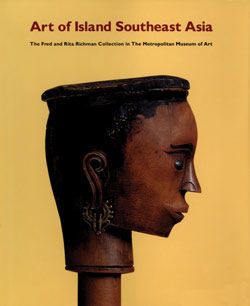

Ancestor figures from Maluku Tenggara (Moluccas Islands) aid in storytelling about ancestors and enable people to communicate with their deceased relatives. While most carvings follow the same conventions – the position of the arms and legs, elongated nose, large piercing eyes – they nevertheless represent a specific individual. Due to the position of the legs, this example from Leti is a male ancestor; male figures are shown with their legs bent and elbows resting on the knees, while female ancestors are typically shown with their legs crossed. The large size of the figure and the depiction of ear ornaments indicate the ancestor here was of high rank when he was alive. The protrusion emerging from the top of the head would customarily be wrapped in a red or white cloth, another indication of status. These carvings would have been commissioned by family members about five days after their relative passed away, and then kept in a secluded area of the house until they were needed. The carvings were brought out and used as a focal point to enable storytelling. Descendants would give the statue offerings of food and wine before consulting the ancestor embodied within to discuss matters of import or were asked to give support and advice before embarking on a significant endeavor. They would also act as mnemonics – similar to a photograph – to spark a memory so that an individual could tell a story about that ancestor, keeping their memory alive.

Speaking the name of the ancestor who is represented by this figure is potentially dangerous, for it is the act of naming that calls the spiritual entity into the carving and brings them into the present. In Southwest Maluku, the act of storytelling is what brings reality into being – a reality that must be harnessed and controlled by whoever named it. Symbols, metaphors, thematic devices, and proverbs are used throughout many artforms in the Malukus, including woven textiles and creation narratives. Each symbol (rou) is given its own name (ktunu) and with that name comes an entire story that takes shape as a narrated reality in the present. The naming of this sculpture functions in the same way and it, too, would have been allocated a name. However, these carvings were largely destroyed or sold when much of Southwest Maluku converted to Christianity, and their names have not been spoken or passed down (rendering them inert and safe to view). Many sources refer to these sculptures as iene (or yene in Indonesian), which is a Letinese word that prohibits an action. In this case, it implies the name of this statue cannot be given. Letinese professor and linguist Aone van Engelenhoven suggests the name iene was possibly misunderstood by early collectors to be the name of this genre of carvings – a name that has been perpetuated in museum records. The term luli dera may be more applicable, for it refers more broadly to a male sacred entity, therefore avoiding any direct reference to the statue and the person it embodies.

Referencesvan Engelenhoven, Aone. Recorded conversation with the MET Digital and Curatorial teams. 21 November 2022.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.