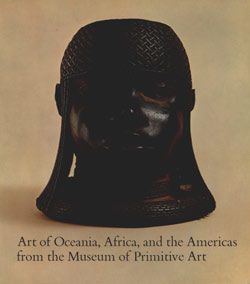

Howling canine

South central Veracruz artist(s)

Not on view

This animated canine, most likely a coyote, rears back its head, howling and baring its teeth. The artist positioned the legs and tail to create a stable tripod base supporting the hollow sculpture. The leash worn like a scarf around its neck, which resembles one found on a dog sculpture excavated at El Faisán in central Veracruz, suggests that this wild coyote may have had a human master (Medellin Zenil 1960:97, Fig. 58). At the site of nearby Nopiloa, a jaguar figurine was uncovered wearing a similar rope around its neck (Medellin Zenil 1987: Fig 87). One imagines that the possession of ferocious, captive animals would have added to perceptions of a ruler’s prowess.

The rough clay surface was left exposed, with only the pupils, upper lip, and rectangular body painted black, using bitumen (chapopote). As a shiny black accent for terracotta sculptures, like this one, bitumen highlights are found on zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figurines throughout central and southern Veracruz, commonly appearing as a ring surrounding the mouth or to darken the pupils of button-like eyes. Two howling canines accented with chapopote were excavated at the Classic Veracruz site of Buena Vista (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa #00163). They are each supported by their four legs, with necks craned at an angle. Less than half the scale of the Howling Canine seen here, they appear more like juveniles. Since the first millennium BCE, Mesoamerican peoples collected, processed, and used tar (bitumen, a sticky, viscous black liquid and a constituent of petroleum), a natural resource in the oil-rich Mexican Gulf Coast. Stored as balls or cakes, it has been found in archaeological sites from the lowlands of the Gulf Coast region to the Central Mexican highlands. The distribution of archaeological bitumen distant from its source indicates that the Olmecs and their Gulf Coast successors traded the substance within and beyond the region to be used as paint, glue, incense, waterproofing, body adornment, and fuel.

Coyotes are a formidable presence in Mesoamerica, and in Mesoamerican imagery. At the Classic period city of Teotihuacan in central Mexico they appear on murals in painted processions or as human warriors in coyote costume; believed to symbolize an elite warrior class (not unlike the Eagle and Jaguar Knights of the later Aztec period). In Veracruz, a terracotta sculpture from the site of Dicha Tuerta, portrays a warrior wearing a coyote headdress, providing evidence for similar warrior groups on the Gulf Coast (Gutiérrez Solana and Hamilton 1977: Fig. 71). Indeed, with his defiant posture and exposed fangs, this canine’s howl may be a war cry.

Cherra Wyllie, 2025

Further Reading

Gutierrez Solana, Nelly and Susan K. Hamilton, Las Esculturas en terracotta de El Zapotal, Veracruz, Universidad Nacional Autonama de Mexico 1977

Lipp, Frank J. 1991, The Mixe of Oaxaca: Religion, Ritual, and Healing. University of Texas Press, 1991

Medellín Zenil, Alfonso, Cerámicas del Totonacapan, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa. 1960

Medellín Zenil, Alfonso, Nopiloa: Exploraciones arqueológicas, Universidad Veracruana, Xalapa, 1987

Museo de Antropología de Xalapa (MAX), Digital Collection of Archaeological Heritage, Universidad Veracruzana de Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico https://sapp.uv.mx/catalogomax/en-US

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.