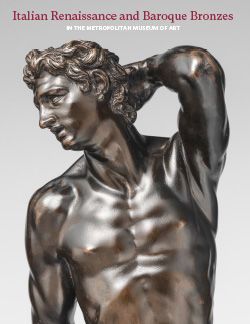

Cupid about to fire an arrow

Not on view

Cupid’s wings, quiver, and arrows are all missing, but the articulated baldric shows the modeler had a nice ornamental touch. The first important question to ask is, Why does the god of love wear a puritanical loincloth? That would seem to eliminate Renaissance or Neoclassical origins. The pose charmingly reiterates that of the Vatican’s ancient marble Laocoön. When in the collection of J. P. Morgan, the piece was catalogued as being a pair with another boy now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (fig. 199a).[1] He is winged with the same upper body and gently faceted garment but with the legs rearranged so as to be running, supported on his bent left leg. The sculptor was able to alter his model before casting to change the meaning altogether, from triumph in our bronze to more athletic activity in the Kansas City one. They had different marble bases, since removed, and were certainly not invented as pendants.

A clumsier version of The Met Cupid, with the same Laocoön conceit, was sold in 1977.[2] Its wings are mounted low on the back, and there is a rather meaningless gash across the left thigh, perhaps in imitation of the folds of a baby’s flesh.

Artist or workshop have thus far eluded scholars. Like its Kansas City counterpart, this Cupid bears marks of distinctive quality, such as the blank oval eyes and tousled curls, and their mix of classicism and naturalism has not yet been encountered elsewhere.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Bode 1910, vol. 2, p. 20, no. 176. The Nelson-Atkins bronze bears an unlikely attribution to Nicolò Roccatagliata.

2. Christie’s, Rome, May 5, 1977, lot 138 (as possibly early 16th century).

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.