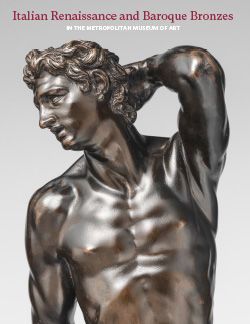

Jupiter (?)

Style of Girolamo Campagna Italian

Not on view

The mature, bearded man with full hair holds his head proudly erect and gazes toward an invisible point in the far distance. He is nude, but his loins are covered with a small piece of cloth held in place by a shoulder strap. His left hand is placed elegantly on his left breast, while the outstretched right arm points downward in an imperious gesture. There is no attribute that could help to identify the figure, which was called Neptune by John Goldsmith Phillips.[1] The quality of the cast is mediocre and the execution rough, with no discernible afterwork. Particularly disturbing are the cut-off toes of the proper left foot. The statuette was probably made as a crowning figure for an andiron, a domestic artifact that did not call for a very sophisticated appearance. Nevertheless, the bronze was considered by Phillips to be “probably by Campagna,” an attribution for which he gave no reasons.

The figure is known in two other versions, one in the Detroit Institute of Arts and one formerly in the Abbott Guggenheim collection. In regard to the latter, Laura Camins believed that it is based on a large sculpture of Istrian stone created by Agostino Rubini in 1588, which was placed among many others on the roof balustrade of the Libreria Marciana in Venice.[2] According to the documents, Rubini’s statue represents Saturn, an identification one would hardly guess since the entirely nude figure lacks any attributes.[3] The similarity of the bronze statuette and the stone sculpture can only be discerned when one pictures Rubini’s Saturn mirror-inverted, but even then the positioning of the arms and head are quite different. The bronze depends thus only very loosely—if at all—on the large model, and neither the claim of Rubini’s involvement in its production nor the identification of its subject as Saturn is compelling.

The statuette in Detroit is the finest of the three bronzes, and its details, particularly the hands, face, and hair, are carefully rendered. The male is accompanied by an eagle behind his left leg, identifying him as Jupiter. His impressive head and commanding gesture are perfectly suited for representing the father of the gods and chief deity of the Roman state religion, and it may be that The Met’s bronze was also meant to depict Jupiter. In regard to the Detroit statuette, Alan Darr basically followed Camins’s claim that the model was created by Agostino Rubini, a thesis that, as argued above, remains inconclusive.[4]

Since the so-called Saturn in the Abbott Guggenheim collection is signed with the letters “IC,” it has been suggested that it was cast by Giuseppe Campagna, brother of Girolamo, a proposal that lacks proof and has rightly been challenged.[5] Although Wladimir Timofiewitsch has demonstrated that Campagna was very probably not involved in the production of small bronzes,[6] Darr nonetheless attributed the Jupiter in Detroit to the workshop of this master. To support the attribution, he referred to another model of Jupiter holding a thunderbolt in the right hand, known in many versions (compare cat. 86), which was given by some scholars to Campagna. However, although this Jupiter with a Thunderbolt has a head, loincloth, and shoulder strap that are similar to those of the Detroit Jupiter, it is otherwise of a totally different composition and style. The comparison demonstrates only that the Detroit statuette is artistically a much more impressive invention than the Jupiter with a Thunderbolt. And indeed, Charles Avery has convincingly attributed the version of the latter in La Spezia to the workshop of Joseph de Levis, who was more a talented founder than a great sculptor.[7]

While the execution of our statuette is poor, its composition is striking. The elegant pose and expressive head are perhaps more reminiscent of Alessandro Vittoria than of Girolamo Campagna, whose work is seldom so powerful. That the creative spirit of such artists can be found even in the common output of local commercial foundries explains the attraction of Venetian bronzes, of which the present work is a perfect example.

-CKG

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. The statuette was also described as Vulcan in The Met’s documentation.

2. Camins 1988, pp. 54–56, cat. 16; see also Schwartz 2008, p. 111, no. 53; Christie’s, New York, January 27, 2015, lot 45, which was not sold and thus went back to Dr. John Abbott. I am grateful to William Russell for this information.

3. Agostino Rubini and his brother Virgilio were paid for the Saturn and Diana statues on Christmas 1588; see Ivanoff 1964, p. 107, according to whom (p. 106) these two statues are today substituted by copies. However, Ivanoff later maintained (1967, p. 57) that the Saturn in place on the balustrade is still the original.

4. DIA, 60.41; see Darr et al. 2002, p. 254.

5. For a discussion of this identification, see cat. 75.

6. Timofiewitsch 1972, pp. 23–24 n. 83.

7. Charles Avery in Ratti and Acordon 1998, p. 174, no. 106.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.