This Weekend in Met History: April 2

General Eisenhower receiving an honorary Fellow for Life award from Roland Redmond, vice president of the Board of Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum, April 2, 1946

The Metropolitan will be a more priceless treasure of the America of centuries hence even than it is today. It is our privilege to pass on to the coming centuries treasures of past ages and to add to these the artistic creations of our own. But now, today, hundreds of returned soldiers will profit by your help in creative effort, and thousands more will gain inspiration from your exhibits. They who have dwelt with death will be among the most ardent worshipers of life and beauty and of the peace in which these can thrive.

—General Dwight D. Eisenhower in an address at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2, 1946

«Sixty-five years ago this weekend, on April 2, 1946, The Metropolitan Museum of Art held a special ceremony inaugurating its seventy-fifth anniversary. One of the highlights of the day was a presentation honoring General Dwight D. Eisenhower in recognition of his oversight of the repatriation of artworks stolen by the Nazis during World War II.» Eisenhower would later serve the Museum as Trustee (1948–1953) and Honorary Trustee (1953–1969). At the ceremony, Francis Henry Taylor (1903–1957), director of the Metropolitan Museum from 1940 to 1954, stated that the award of honorary Fellow for Life to the Museum was "in a sense, more than a gesture by the entire academic world to the man, who, more responsible than any other, has made it possible for the world of great civilization in the past to continue for future generations," (New York Times, April 3, 1946). In honor of the Museum's seventy-fifth year, or Diamond Jubilee, the ceremony also launched a fund drive to raise $7.5 million for new construction.

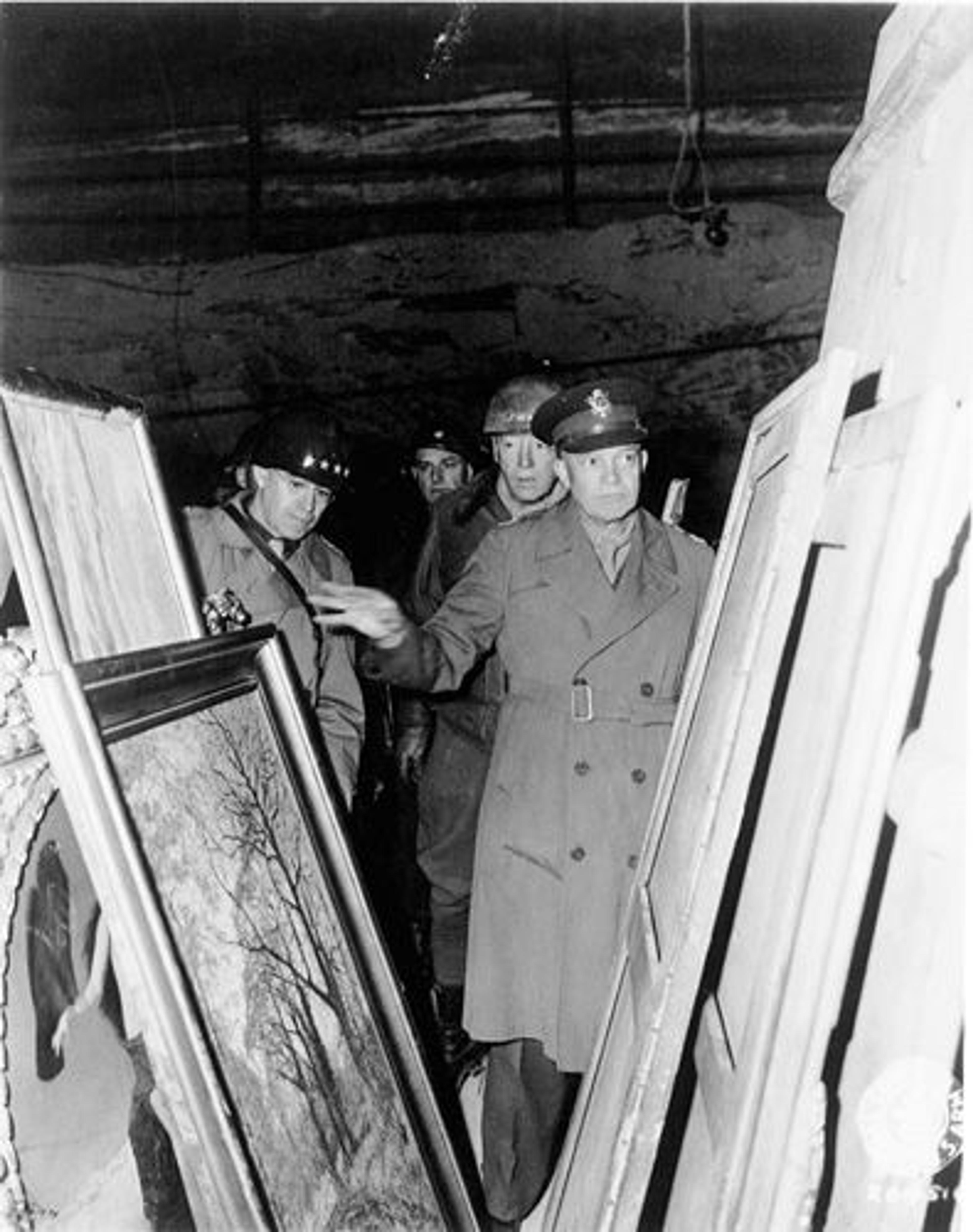

Left: April 12, 1945: General Eisenhower, supreme Allied commander, inspects art treasures looted by the Nazis and stored away in the Merkers salt mine. Behind Eisenhower are General Omar N. Bradley (left), commanding general of the Twelfth Army Group, and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr. (right), commanding general, Third U.S. Army. National Archives and Records Administration, RG 111-SC-204516

Immediately following the war, hundreds of important objects were saved and repatriated by a group of military personnel and civilians known as the "Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section." Although it was nicknamed the Monuments Men, the group included women, notably Edith Standen (1905–1998), a member of the Women's Army Corps who later joined the staff of the Metropolitan. Standen became one of the world's leading tapestry experts, retiring in 1970 and remaining a consultant to the Museum until 1988. Other Museum staff who served in the group were James J. Rorimer (1905–1966), director of the Museum from 1955 to 1966, Theodore Rousseau Jr. (1912–1973), who held several positions at the Museum from 1946 to 1973—including chief curator and vice director—and Theodore Heinrich (1910–1981), who was associate curator of paintings from 1953 to 1955. (Met Director Francis Henry Taylor served on the Roberts Commission, also known as the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, which worked together with the Monuments Men to save and repatriate works of art.)

Spectators filled the Museum's Great Hall and surrounding balconies for the ceremony on April 2, 1946.

The ceremony honoring Eisenhower was attended by hundreds—including Francis Cardinal Spellman—and was broadcast via loudspeaker throughout the Museum. The proceedings were recorded on fragile 78-rpm glass-based 12" lacquer discs that sat silent for decades in the Watson Library and the Museum Archives until last year, when the Museum received a grant from the Monuments Men Foundation to preserve, digitally remaster, and publish these unique audio recordings online. They are now accessible as part of the Museum libraries' digital collections.

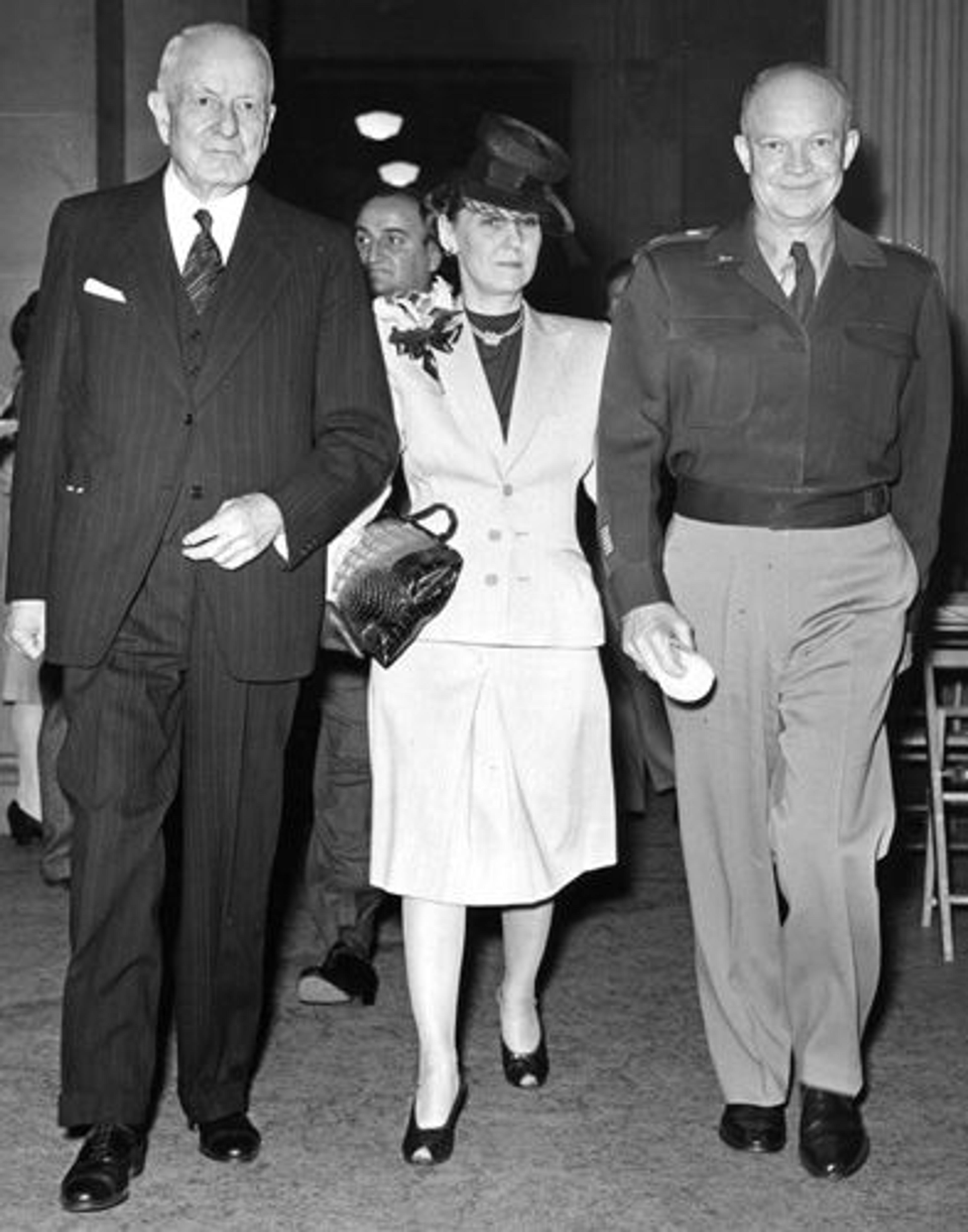

Right: Thomas J. Watson, Mrs. Eisenhower, and General Eisenhower arriving at the Museum on April 2, 1946

Listen to Eisenhower's speech.

Audio recording of General Eisenhower's address on April 2, 1946. See below for a transcript. Additional photographs of the event and recordings and transcripts of the speeches are available in the digital collections.

In addition to honoring General Eisenhower and the work of the Monuments Men, the ceremony also marked the beginning of the Museum's campaign to raise $7.5 million for the renovation and reconstruction of existing buildings and the construction of several new wings, in celebration of the Museum's seventy-fifth anniversary. Thomas J. Watson, chairman of the seventy-fifth anniversary committee, stated: "In three generations the Museum has become one of the world's greatest treasure houses and educational institutions. However, its rapid growth has resulted in overcrowding of collections." He went on to say that the goal of the fund-raising was "to transform one of the finest cultural institutions in our land so that everyone, from every walk of life, in this generation and the generations to come, may learn through art more of the history of our civilization which our guest of honor has striven so ably to preserve."

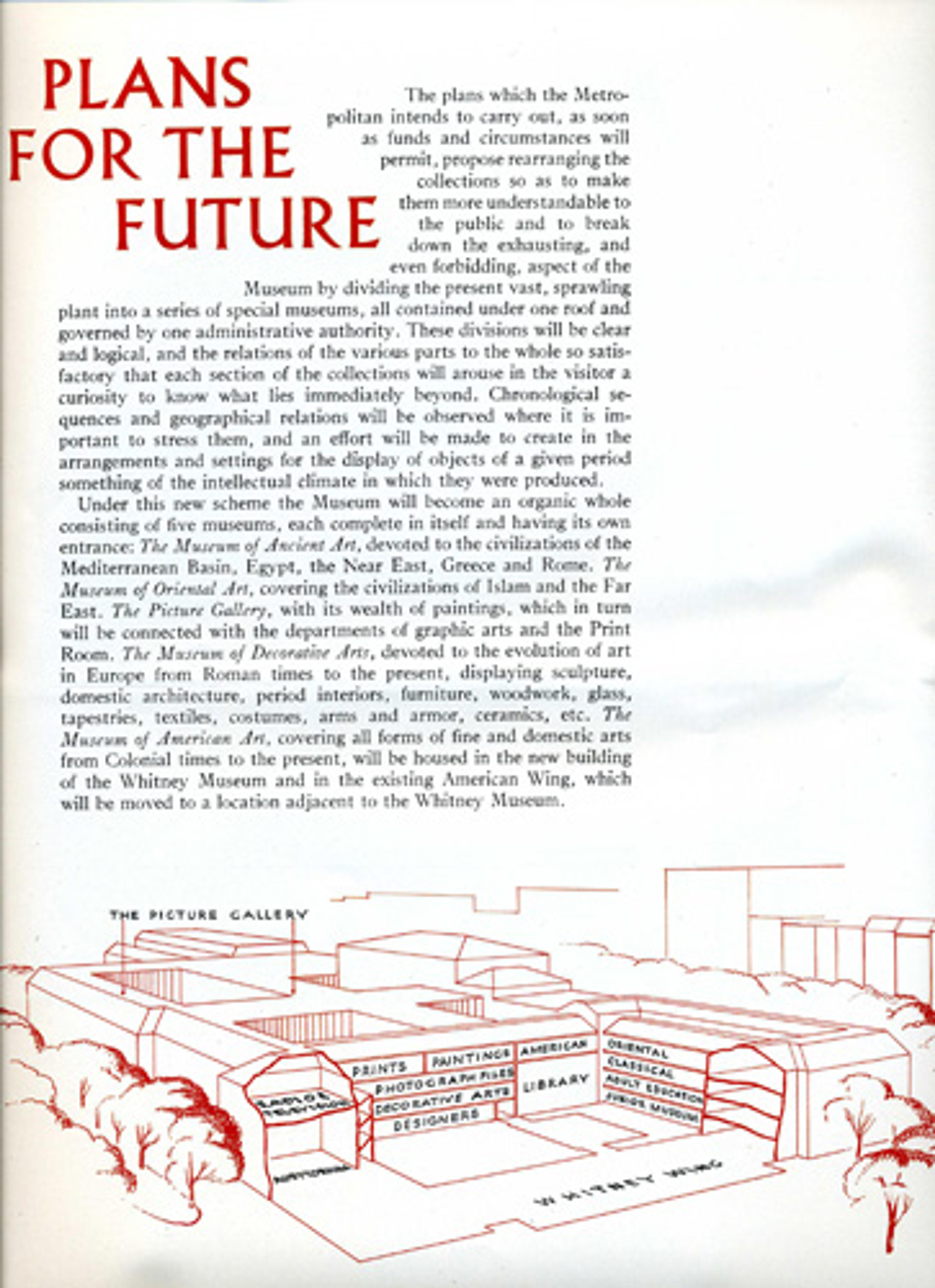

Watson then outlined an ambitious plan to transform the institution into five separate museums under one roof. Each would be a stand-alone museum with its own entrance. In a 1946 brochure the Museum elaborated its intentions for the projected new wings, which included a possible collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Left: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Educational Services brochure about the construction plans, 1946

The plan would cost more than $10 million. The City of New York was to contribute funds for reconstruction and modernization, the Whitney Museum was to pay for the wing it would occupy, and an additional $7.5 million was to be raised by the Metropolitan. In the end, the Whitney collaboration fell through and many design elements of the original proposal had to be scaled back, but Diamond Jubilee campaign funds were committed to a successful gallery refurbishment and expansion program that commenced in 1950.

Barbara File is archivist in the Museum Archives.

Related Publications

Edsel, Robert M., and Bret Witter. The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York: Center Street, 2009.

Edsel, Robert M. Rescuing Da Vinci: Hitler and the Nazis Stole Europe's Great Art: America and Her Allies Recovered It. Forewords by Lynn H. Nicholas and Edmund P. Pillsbury. Dallas: Laurel Pub., 2006.

Feliciano, Hector. The Lost Museum: The Nazi Conspiracy to Steal the World's Greatest Works of Art. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Rorimer, James J., and Gilbert Rabin. Survival: The Salvage and Protection of Art in War. New York: Abelard Press, 1950.

Smyth, Craig Hugh. Repatriation of Art from the Collecting Point in Munich after World War II: Background and Beginnings with Reference especially to the Netherlands. Maarssen: Gary Schwartz; Montclair, NJ: Distributed in North America by Abner Schram, 1988.

"The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1940–1950: A Report to the Trustees on the Buildings and the Growth of the Collections," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 8, No. 10, Jun., 1950, pp. 281–324.

Transcript of Dwight D. Eisenhower's Address at the Metropolitan Museum on April 2, 1946

Mr. Chairman, Your Eminence, fellow Americans, before proceeding I should like to take a few seconds to attempt to express something of the very humble but very deep pride that Mrs. Eisenhower and I take in the cordial welcome that we have received here today. I think no man can achieve a higher place in this world than to feel that those with whom he comes in contact are glad to see him. Mrs. Eisenhower and I certainly have that feeling today and we are very proud and very grateful.

We have recently emerged from a bitter conflict that long engulfed the larger nations of the globe. The heroism and sacrifice of men on the fighting lines and the moral and physical energies of those at home were all devoted to the single purpose of military victory. Preoccupation in a desperate struggle for existence left time for little else. Now we enter upon an era of widened opportunity for physical and spiritual development, united in a determination to establish and maintain a peace in which the creative and expressive instincts of our people may flourish. The welcome release from the fears and anxieties of war will, as always, be reflected in a resurgence of attention to cultural values.

It may seem strange that a soldier, representative of the science of destruction, should appear before a body dedicated to the preservation of man's creative ideals as expressed in art, and should be urging support of the Metropolitan Museum. Even though we acknowledge that the soldier's true function is to prevent rather than to wage war, yet his necessary association with lethal weapons would seem to imply the existence of an unbridgeable gulf between his philosophy and that of the artist. Perhaps this is so; certainly I lay no claim to artistic temperament. But I do know that for democracy, at least, there always stand beyond the materialism and destructiveness of war the ideals for which it is fought. Thus the awful test of war is primarily a testing of the spirit, and so it is possible for the fighting man to experience in war a definite spiritual growth.

But for simpler reasons than these I believe that many of our veterans have gained renewed interest in art and in the world of artists. In foreign lands American soldiers have made new contacts with portions of mankind's vast heritage of culture. Many have been awakened to the permanent value of beauty as expressed in architecture, sculpture, painting, and the folk arts. Prompted by curiosity, respect, and interest, thousands of America's fighting men have spent countless hours touring the art centers of Europe and the Orient.

Just after the termination of our Kasserine crisis in North Africa, somewhere toward the end of April 1943, in returning to advance headquarters one day, I drove past the ancient city of Timgad. It was by the nearest road—a miserable road—to the nearest soldiers of the United States, seventy-five miles. It was a rainy, drizzly, miserable, cold day. I had but a short time to stop there, but I found a lieutenant who had secured a weapons carrier for the day and had loaded it up with soldiers. First I was struck by the fact that in all North Africa, in the area around Constantine, these soldiers found a visit to the site of an ancient culture more interesting than anything else, in spite of the hardships of the trip. And then I was struck by the attitude of those soldiers walking over the old roads where chariots of twenty-five hundred years ago had rolled their way up to the forum. It was an attitude not of flippancy, almost of veneration. You could close your eyes and almost see those men with the togas of the senators on them, because they seemed to bring themselves so close to something that had happened that long ago.

These same soldiers have seen the destruction of priceless artistic treasures, but—and perhaps understandably—this fact has served only to increase their respect and veneration for civilizations of the past. They tried within—sometimes beyond—the limits of military prudence to protect and preserve these products of man's creative instinct. But war is essentially destruction. An army at war must incessantly hurl destructive force at the enemy, and in this process much of the world's heritage in art has been inevitably damaged and lost in the late global conflict.

I am grateful to the directors of the Metropolitan Museum for their generosity in having accorded me an honorary membership for my small part in protecting these monuments. The credit belongs to the officers and men of the combat echelons whose veneration for priceless treasures persisted even in the heat and fears of battle.

Another view of the fate of art in war was presented to our soldiers when, at long last, we penetrated to the heart of Nazism. There, in caves, in mines, and in isolated mountain hideouts, we found that Hitler and his gang, with unerring instinct for enriching themselves, had stored art treasures filched from their rightful owners throughout conquered Europe. Alongside bar and minted gold were found paintings, statues, tapestries, jewelry, and all else that the Nazis knew mankind would pay much to rescue and to preserve. Some of this has been restored. Some, not easy to identify, is still under the care of the captors.

Frequently the soldier was led to express in artistic fashion something of his own reactions to the phenomena of war. At least you are acquainted with the efforts of our friend Mr. Mauldin in this regard, who spared no pains to show what he thought of us brass hats.

Possibly none of the paintings and drawings that the American soldier brought back with him will ever find its way into the Metropolitan, but they are to him, in sum, vivid memories of filth and beauty, of hopes and fears, of suffering and mercy, of life and death. Moreover, they provide additional evidence that thousands of our returned soldiers will eagerly seize upon the opportunities offered by the Metropolitan and its sister institutions of art.

The freedom enjoyed by this country from the desolation that has swept over so many others during the past years gives to America greater opportunity than ever before to become the greatest of the world's repositories of art. The whole world will then have a right to look to us with grateful eyes, but we will fail unless we consciously appreciate the value of art in our lives and take practical steps to encourage the artist and to preserve his works. In no walk of life can man fail to find richer experience as he falls under the influence of beauty immortalized by inspired genius. Even for the roughest of soldiers there is more of ancient Egyptian history to be felt and understood in a lonely, graceful column rising against the sky in a naked field than there is in all the descriptive matter that was written on the subject.

The Metropolitan will be a more priceless treasure of the America of centuries hence even than it is today. It is our privilege to pass on to the coming centuries treasures of past ages and to add to these the artistic creations of our own. But now, today, hundreds of returned soldiers will profit by your help in creative effort, and thousands more will gain inspiration from your exhibits. They who have dwelt with death will be among the most ardent worshipers of life and beauty and of the peace in which these can thrive.

Barbara File

Barbara File is an archivist in the Museum Archives.