Medieval Art and The Cloisters

The Museum's collection of medieval and Byzantine art is among the most comprehensive in the world. Displayed in both The Met Fifth Avenue and in the Museum's branch in northern Manhattan, The Met Cloisters, the collection encompasses the art of the Mediterranean and Europe from the fall of Rome in the fourth century to the beginning of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. It also includes pre-medieval European works of art created during the Bronze Age and early Iron Age.

Although the fledgling Metropolitan Museum acquired its first medieval object in 1873, the core of the collection in the Main Building was not formed until nearly fifty years later, in 1917, when the son of the financier and collector J. Pierpont Morgan donated some two thousand medieval objects that had belonged to his father. The collection has continued to grow through purchases, gifts, and bequests. More than 250 medieval objects came to the Museum from the banker and prodigious collector George Blumenthal in 1941. Others who have contributed substantially to the collection include Michael Friedsam, George and Frederic Pratt, and Irwin Untermyer.

Much of the sculpture at The Cloisters was acquired by George Grey Barnard, a prominent American sculptor and avid collector of medieval art. While working in rural France before World War I, Barnard supplemented his income by locating and selling medieval sculpture and architectural fragments that had made their way into the hands of local landowners over several centuries of political and religious upheaval. Barnard also served as a middleman between major Paris dealers and American clients. However, he kept many pieces for himself and, upon returning to the United States, opened to the public a churchlike brick structure on Fort Washington Avenue filled with his collection—the first installation of medieval art of its kind in America.

In 1925 the American philanthropist and collector John D. Rockefeller Jr. provided funds that made it possible for the Museum to acquire Barnard's collection and also financed the conversion of nearly sixty-seven acres of land into a public park to house the new building. Rockefeller donated seven hundred acres to establish additional parkland along the New Jersey Palisades, ensuring that the view from across the Hudson River from The Cloisters remain unsullied. The Cloisters building, designed by Charles Collens, the architect of New York City's Riverside Church, in a simplified medieval style, was formally dedicated on May 10, 1938.

In recent years, galleries in both locations have undergone dramatic renovations. In the Main Building these include new galleries for Byzantine Art and for Medieval Art up to 1300, funded by Mary and Michael Jaharis. Most recent at The Cloisters is the renovation of the Late Gothic Hall, completed in 2009, which included the conservation of windows from the Dominican monastery in Sens and the return to public view of a monumental tapestry from Burgos Cathedral.

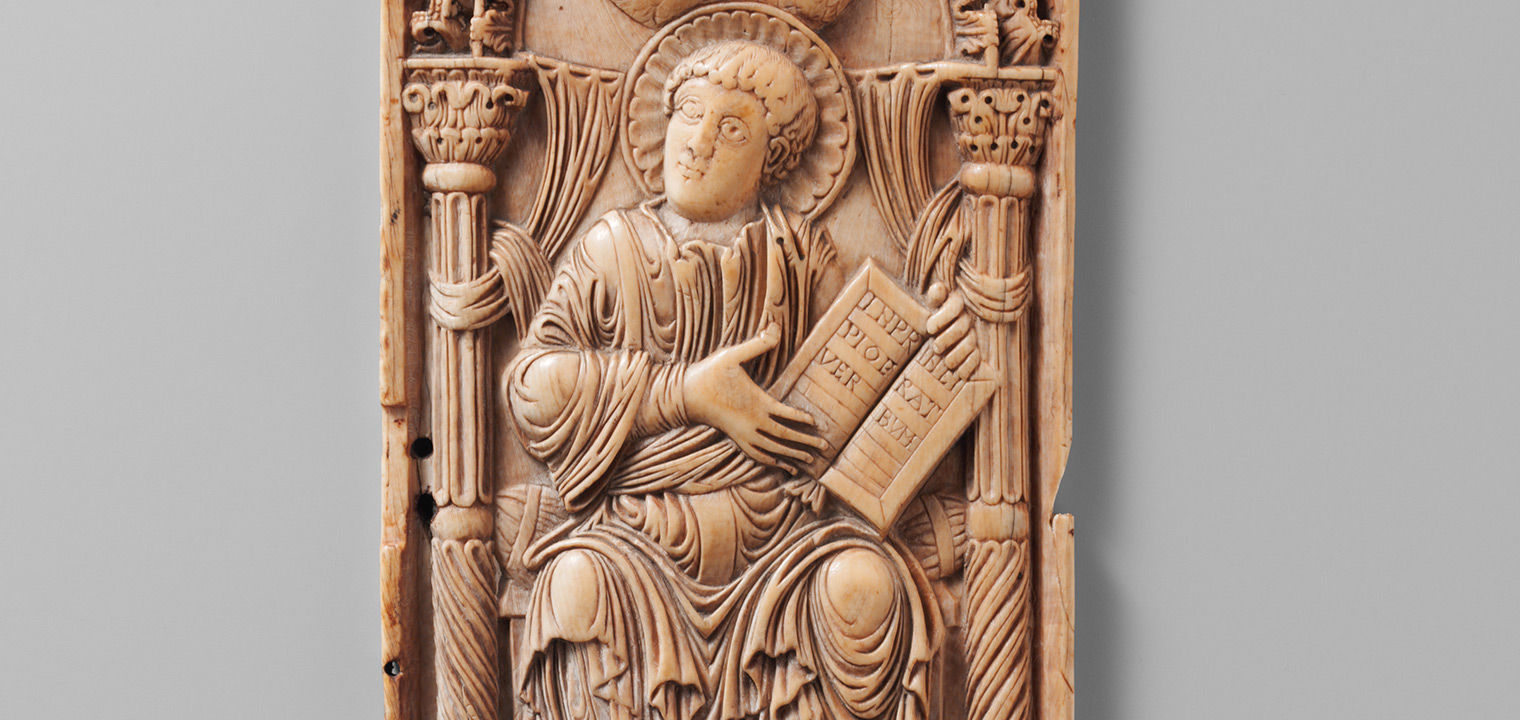

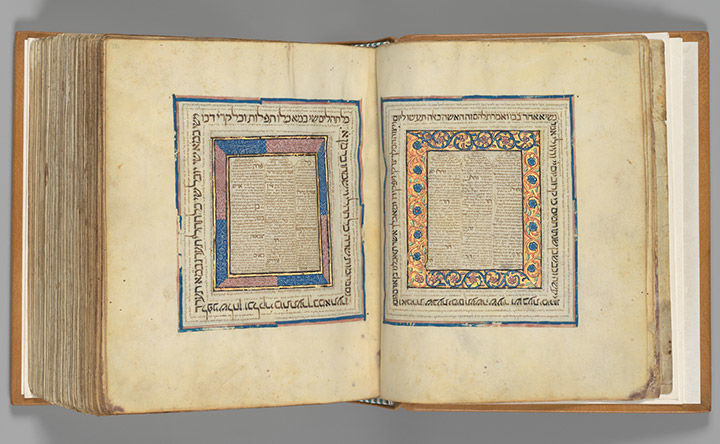

Both collections continue to acquire works of art. A Carolingian ivory, The Jaharis Lectionary, a Limoges plaque with angels, and a painted glass paten are among the masterworks added to the collection since 1999.

The Met Cloisters, the Museum's branch dedicated to the art and architecture of medieval Europe, is located on four acres overlooking the Hudson River in northern Manhattan's Fort Tryon Park. It is named for the portions of cloisters from present-day France—Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Trie-sur-Baïse, Froville, and elements once thought to have come from Bonnefont-en-Comminges—that were incorporated into a modern museum building.

Three of the cloisters (Cuxa, "Bonnefont," and Trie) feature gardens—planted according to horticultural information found in medieval treatises and poetry, garden documents, and herbals. The overall effect is not a copy of any specific medieval structure but rather a harmonious and evocative setting for approximately 2,000 works of art, a rich selection of objects and architectural elements from the medieval west largely dating from the twelfth through the fifteenth-century.

The Treasury contains small-scale works of exceptional splendor. On display is a richly carved English ivory cross of the twelfth century, as well as the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, a masterpiece in miniature by the illuminator Jean Pucelle, and a book of hours created for the great medieval book collector, Jean of France, Duke of Berry. A gallery devoted to late medieval private devotion presents the celebrated Merode Triptych by the Netherlandish master Robert Campin. The Late Gothic Hall exhibits many of the finest fifteenth- and sixteenth-century works in the collection, including sculptures by Tilman Riemenschneider and altarpieces from Spain. Particularly beloved is the gallery that features the seven tapestries showing The Hunt of the Unicorn. Throughout The Met Cloisters are exceptional examples of stained-glass windows, including those from the castle chapel at Ebreichsdorf, Austria, and the Carmelite church at Boppard-am-Rhein.

More than 1,400 objects on view in The Met Fifth Avenue allow visitors to trace the history of medieval and Byzantine Art, from their roots in Celtic and late Roman art to the sumptuous objects of late medieval courts and the ecclesiastical riches of Late Byzantium and its eastern neighbors. The collection boasts an abundance of works from Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine periods. The renowned Second Cyprus Treasure, with its plates representing the life of the biblical King David, is one of several silver and gold treasures on view. Byzantine Egypt is particularly well represented by an impressive collection of textiles as well as architectural fragments and tomb monuments from the Museum's early twentieth century excavations at Bawit and Saqqara. An extensive collection of early medieval art, which comprises the jewelry of Anglo-Saxons, Franks, and Visigoths, among other peoples, highlights the artistic achievements of western Europe at the same moment.

An evocation of a Byzantine church sanctuary, replete with icons and a lectionary from the church of Hagia Sophia, makes plain the Museum's rich collection of art from the Greek East from 800 to 1500. The same period in the Latin West saw the emergence of the Church as the most important patron of the arts, and several galleries testify to the splendid holdings of Western monasteries and churches. Relic containers, book covers, and a tabernacle are among the many noteworthy objects from the Museum's collection of enamels by Limoges goldsmiths. A set of works from eleventh and twelfth-century Spain includes ivory carvings and leaves from a Beatus manuscript. Masterworks of sculpture and stained glass from such key monuments as the royal abbey of Saint-Denis outside Paris, Notre-Dame in Paris, and the cathedral of Amiens evoke the great age of church building. Also on view is an array of ivories from the Gothic period, while luxury tableware and a rotating display of tapestries recall the world of late medieval aristocrats.

Collection Highlights

See highlights of medieval art and The Cloisters Collection.

The Gardens of The Met Cloisters

Designed as an integral feature of the Museum, the gardens have been a major attraction of The Cloisters since its opening in 1938, enhancing both the setting in which the Museum's collection of medieval art is displayed and the visitor's understanding of medieval life. Explore the gardens and plant lists

Designed as an integral feature of the Museum, the gardens have been a major attraction of The Cloisters since its opening in 1938, enhancing both the setting in which the Museum's collection of medieval art is displayed and the visitor's understanding of medieval life. Explore the gardens and plant lists

Related Content

Publications

Discover The Met's many publications on medieval art and The Cloisters.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Browse richly illustrated essays on medieval art and architecture.

Blog Articles

Fresh perspectives on medieval art from curators and others at the Museum.

Videos

Watch videos about medieval art and The Cloisters—interviews, lectures, exhibition previews, and more.

Stay Connected

Meet the Staff

Get to know the people who care for the art.

Meet the Fellows

Get to know the 2022–2023 Fellows for Medieval Art and The Cloisters.