Installation view of Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past in the Koç Family Gallery 460

As modern-day Turkey marks its hundredth year, Koç Family Galleries 459 and 460 devoted to the arts of the Ottoman world, highlight seven modern and contemporary works that engage with the Islamic and Ottoman cultural legacy. These works reflect the creative approaches to the Ottoman past pursued by three generations of artists from Turkey and elsewhere. Some take pride in their links to historical traditions; others reject that legacy but remain subconsciously rooted in Ottoman culture. Modern preoccupations include the arts of calligraphy and ornament, along with the traditions of manuscript painting, textile weaving, and ceramics production. By repurposing these hallmarks of Ottoman art, some artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries confront gender, taboos, and other aspects in modern Turkey.

This intervention puts the modern and contemporary works into conversation with their Ottoman forebears to ask the following questions: What defines modern Turkish art? How does it differ from “craft,” especially in light of Turkey’s rich ceramic and textile traditions? Each of the featured artists has developed a distinct artistic identity by employing, renewing, or diverging from the styles, modes, and creative traditions of the Ottoman past—while also incorporating the methods and principles of twentieth and twenty-first century Turkish, European, and American art. The dialogues between these modern and historical works bridge gaps of time and space to join a greater, global dialogue of modernity.

The installation Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past was on view from October 23, 2023 through December 2, 2024. It was organized by Deniz Beyazit, Curator in the Department of Islamic Art. The digital content was designed by James Dill, Associate for Administration in the Department of Islamic Art.

The installation was made possible by The Turkish Centennial Fund.

Engaging with Calligraphy

Left: Ribbon Mania by Burhan Doğançay, American, born Turkey, Istanbul (1929–2013). Made in Turkey, dated 1982. Acrylic on canvas; Height 60 in. (152.4 cm), Width 60 in. (152.4 cm), Depth 1 1/8 in. (2.9 cm). Gift of Benjamin Kaufmann, 2011 (2011.583); Right: Tughra (Insignia) of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66). From Turkey, Istanbul, ca. 1555–60. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; Mat: Height 25 in. (63.5 cm), Width 30 in. (76.2 cm). Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.149.1)

Rooted in Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and other mid-twentieth century movements from Europe and the United States, Doğançay’s work also engaged with the Ottoman past, particularly through calligraphy, an art form that was formative to his artistic output of the 1970s. The artist acknowledged the calligraphic allusions in his work, which were at first subconscious and later deliberate.

Ribbon Mania is one piece in Doğançay’s Ribbons series, inspired by the graffiti-and poster-covered walls of populous cities. While the markings on this canvas suggest posters peeling from a wall, they also recall the Ottoman tughra, a sultan’s royal calligraphic emblem, such as the luxurious example in The Met’s collection of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566). Parallel forms produce lines reminiscent of the tughra’s three vertical shafts, and large curves evoke its oval loops. Like a modern calligrapher, Doğançay created his own script with letters composed of light, shadow, color, and shape. The “ribbons” become trompe-l’oeil creations—slashed and torn paper seems to break through a wall and cast shadows in an interplay of geometric and calligraphic forms.

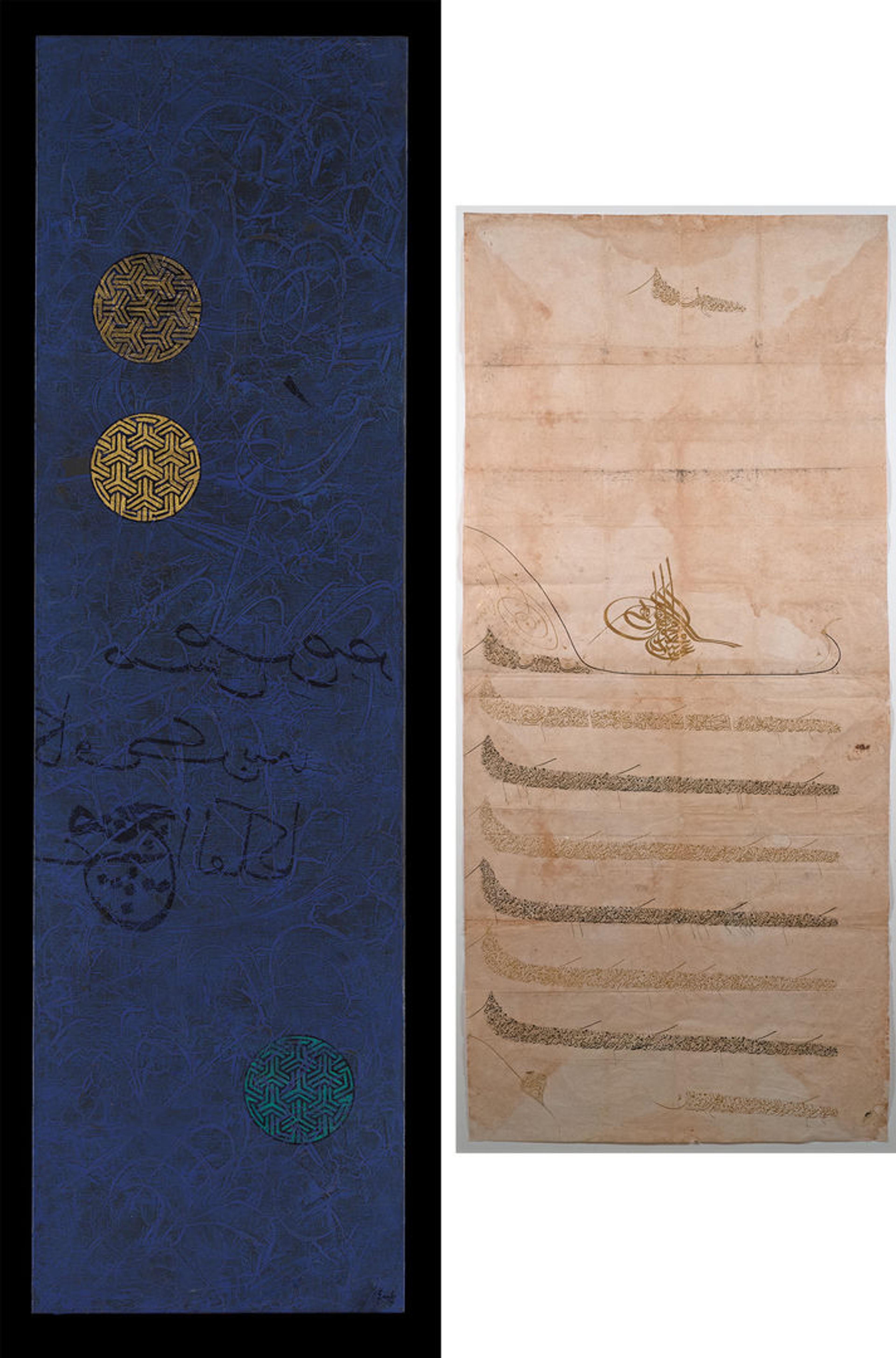

Left: Ferman by Erol Akyavaş (Turkish, 1932–1999). Turkey, 1992. Acrylic on canvas; Height 68 7/8 in. (174.9 cm), Width 19 3/4 in. (50.2 cm). Gift of Mrs. Ilona Akyavaş, 2017 (2017.236); Right: Firman (Official Decree) of Sultan Abdülmecid I (r. 1823–1861). From Turkey, Istanbul, dated January 1848. Ink, and gold on paper; backed onto cloth; With Frame: Height 66 in. (167.64 cm), Width 33 in. (83.82 cm). Private Collection of Seran and Ravi Trehan, New York. (Please note that this object is not part of the installation)

Erol Akyavaş is known for a style that merges the abstraction found in modern European and American art with East Asian and Middle Eastern motifs. Although calligraphy was considered traditional and “backward” in the early decades of the Turkish Republic, Akyavaş began to experiment with transforming Arabic letters in the late 1950s. The large painting “The Glory of the Kings” from around 1959 (MoMA, 130.1961) attests from this early period in the artist’s career. The shape and name of The Met’s work references a firman, an Ottoman royal decree issued on a long paper scroll with the ruling sultan’s royal signature (tughra). Like a firman, this painting is covered with inscriptions—however, Akyavaş’s letters are abstract, pseudo-calligraphic forms, arbitrarily arranged and, at times, upside-down or reversed. Lines, curves, and calligraphy applied to the dark blue-purple background play with light and depth, and three circular motifs evoke seals on documents or might relate to Akyavaş’ interest in maze motifs. The layered composition, illegible letters, and modern minimalist abstraction draw the viewer into the blue color and into a meditative homage to the Ottoman firman.

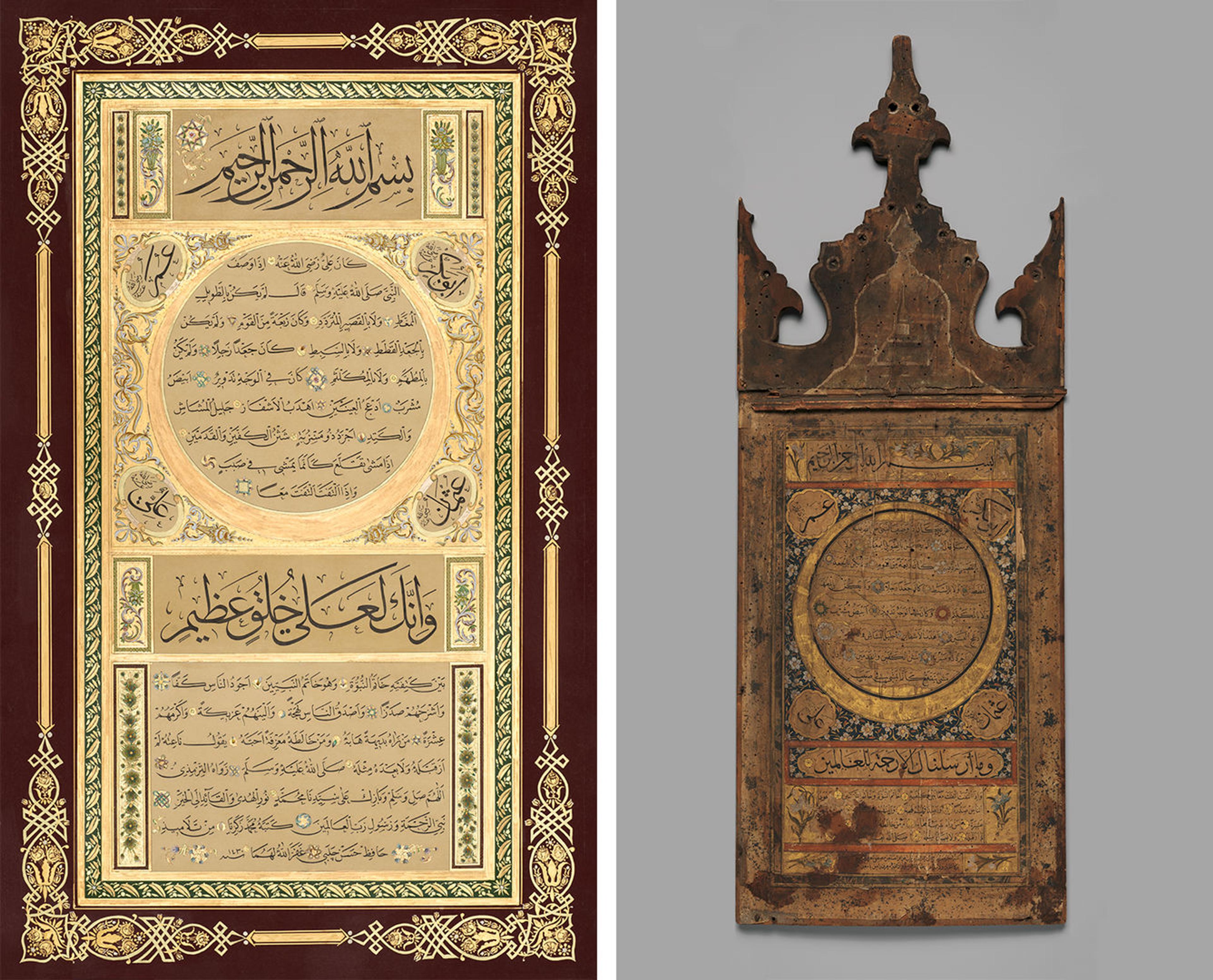

Left: Red Hilye by Mohamed Zakariya (American, born 1942). United States, 2010. Ink, hot tempera, and gold alloy on ahar paper; Height 29 in. (73.7 cm), Width 18 in. (45.7 cm). Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art, 2020 (2022.497); Right: Hilye (Votive Tablet). Attributed to Turkey, Istanbul, Ottoman period (1299–1923), 18th century. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; wood; Height 27 7/8 in. (70.8 cm), Width 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm). The Grinnell Collection, Bequest of William Milne Grinnell, 1920 (20.120.274)

A hilye is a written description of the prophet Muhammad and is associated with protective virtues. The anthropomorphized layout used in the above examples emerged in the seventeenth century Istanbul and was established by court calligrapher Hafiz Osman (1642–1698). A central “belly” (göbek) bearing Muhammad’s description is encircled by a golden crescent. The roundels in the corners name the four “Rightly Guided Caliphs” (Rashidun). The upper panel is the “head station” (baş makam) with the basmala invocation; the lower panel contains a verse from the Qur’an. The “skirt” (etek) at the bottom houses the artist’s signature. To maximize protection, the Ottoman hilye on the right depicts the holy city Medina at top.

The Red Hilye by the contemporary master of calligraphy, Mohamed Zakariya, employs the standard layout developed in the Ottoman Empire during the seventeenth century (see the wood-mounted hilye right). Zakariya’s study of the classical tradition of calligraphy is evident from his immaculate design, style, and inscribed content. The outermost border combines decorative motifs from different periods of the Ottoman artistic tradition, ultimately presenting the hilye from a fresh perspective.

History, Gender, Society

Left: Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) by Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian, born Turkey, 1958). United States, New York, 2007. Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper; twenty-five folios in an embossed box; Box: Height 13 1/2 in. (34.3 cm.), Width 5 1/2 in. (14 cm.), Depth 2 3/4 in. (7 cm.). Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z); Right: Detail of Textile Fragment with Tulips and Pomegranates. Turkey, probably Istanbul, Ottoman period (1299–1923), mid-16th century. Silk, metal wrapped thread; lampas (kemha); Textile: Height 24 in (61 cm), Width 26 1/2 in (67.3 cm). Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1952 (52.20.22)

Peter Hristoff’s complex works present a play of different visual and conceptual layers. This work (left) is a series of twenty-five mixed-media montages that rest in a black silk box. Each sheet’s backmost layer consists of pages taken from an Ottoman etiquette book (görgü kuralları) and adhered to pink Chinese rice paper. This material combination evokes Turkey and China’s long history of cultural exchange via the Silk Road.

The next layer is inspired by Ottoman bahnames, erotic manuals that were variously popular and taboo since they first appeared in the sixteenth century. Hristoff depicts human body forms and genitalia in his characteristic style, alongside roses, tulips, and palmettes—motifs drawn from the Ottoman decorative repertoire and often seen on silk textiles.

Left: Carpet with Double-Ended Triple Niche. Made in probably west-central Turkey, 18th century. Wool (warp, weft and pile); symmetrically knotted pile; Height 75 in. (190.5 cm), Width 54 in. (137.2 cm). The James F. Ballard Collection, Gift of James F. Ballard, 1922 (22.100.65); Center: Sharp Things by Gülay Semercioğlu (Turkish, born 1968). Turkey, Istanbul, 2013. Steel wire and screws on wood; Height 63 3/4 in. (162 cm), Width 44 1/16 in. (112 cm), Depth 2 1/8 in. (5.4 cm). Gift of Öner Kocabeyoğlu, 2014 (2014.132); Right: "Bellini" Carpet. Made in probably Western Turkey, 17th century. Wool (warp, weft and pile); symmetrically knotted pile; Height 69 in. (175.3 cm), Width 53 in. (134.6 cm). The James F. Ballard Collection, Gift of James F. Ballard, 1922 (22.100.89)

This work by contemporary artist Gülay Semercioğlu, although meant to be an abstract creation, resembles a pair of sharp items facing one another. The multiple layers of densely woven metal wires create an interplay of light and color that changes depending on the position of the viewer. Characteristic of Semercioğlu’s signature style, patterns and textures mimic a painter’s brushstrokes to balance color, space, shape, and surface, with a result that evokes a finely executed abstract color field painting. The work embodies the artist’s preoccupation with gender issues through material references to the labor divisions of Turkish society. The stiff, harsh anodized wire is a product of the male-dominated metal industry. The wires’ interlacing alludes to the longstanding, traditionally feminine weaving crafts of Turkey. Sharp Things can be compared to smaller kilims and rugs woven by unknown women in rural and nomadic Turkey, such as Ottoman prayer rugs made of pile.

Reinventing Ceramics

Left: Pregnant Haliç II by Elif Uras (Turkish, born 1972). Turkey, Iznik, 2015. Stonepaste; underglaze painted; Height 24 in. (61 cm), Width 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm), Depth 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). Gift of Öner Kocabeyoğlu, 2016 (2016.76); Right: Ewer with 'Tughra-Illuminator' Style Decoration. Made in Turkey, Iznik, 1525–40. Stonepaste; painted in blue under transparent glaze; Pitcher: Height 8 13/16 in. (22.4 cm), Width 7 7/16 in. (18.9 cm), Max. diameter 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1966 (66.4.3a, b)

Elif Uras’s work pays tribute to Turkish women and to Anatolia’s material and cultural past. Since 2007, Uras has engaged the artistic traditions of the town of Iznik, celebrated for its ceramic production during the Ottoman Empire. Today, tasks that were historically performed by men are managed by women artisans and entrepreneurs. Uras’s voluptuous vessels center the female figure, sometimes evoking the pregnant belly, in an homage to the modern women of Iznik. Pregnant Haliç II takes its name, spiraling floral decoration, and blue-and-white color palette from a group of sixteenth century Iznik ceramics discovered in the Haliç (Golden Horn) neighborhood of Istanbul.

Left: Broken II by Burçak Bingöl (Turkish, born 1976). Turkey, Istanbul, 2013. Stoneware, transfer-printed and glazed; glue, wood; Height 28 5/8 in. (72.7 cm), Width 28 3/4 in. (73 cm), Depth 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm). Gift of Monika McLennan, 2016 (2016.304); Right: Tile Panel. Made in Turkey, Iznik, second half 16th century. Stonepaste; polychrome painted under a transparent glaze; Height 38 3/16 in. (97 cm), Width 38 1/2 in (97.8 cm), Depth 1 7/16 in. (3.7 cm). Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.2084)

Broken II is part of a series in which the Turkish artist Burçak Bingöl questions Turkish society and heritage by repurposing its cultural narratives and deconstructing its everyday items. Here, irregularly broken ceramic pieces have been reassembled perpendicularly in a three-dimensional square panel. This work connects modern artistic practices to the traditional colorful ceramics produced throughout the centuries in the Islamic world. The rose decorations on the tile were transferred from an industrial pattern, but they recall the handmade motifs of Ottoman art, where the flower had both decorative and symbolic uses. The artist was inspired by fragments of ceramic tiles she perceived on Ottoman monuments in Istanbul and elsewhere in Turkey, a reflection of the historic layers of buildings and of societies. The title may allude to what is “broken” in modern Turkish society, yet the work also reveals the beauty that can be found in what is shattered. Broken II is Bingöl’s response to the French modernist Marcel Duchamp’s concept of “readymade” art—art made by recasting already-existing objects.

View select objects in Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past

Installation views of Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past in the Koç Family Gallery 459

Also On View

Untitled (Whirling Dervishes) by Aliye Berger (Turkish, 1903–1974). Turkey, Istanbul, ca. 1960. Etching on paper; Height 12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm), Width 15 1/4 in. (38.7 cm). Gift of Hristoff Family Archives, 2017 (2017.146)

Aliye Berger was one of modern Turkey’s earliest woman artists and most original printmakers. In her distinct expressionist style, she depicted daily life in Turkey through street scenes, landscapes, and city views, as well as more traditional subjects. This print features dervishes, members of a Sufi order known for their ecstatic rituals, among these the practice of “whirling” dance while in prayer. Berger, like many printmakers, worked over and sometimes hand-colored her prints after their production. Because this etching has not been reworked, it is unclear whether it is finished.

Berger’s print was shown in The Patti Cadby Birch Gallery 450, in commemoration of the 750th anniversary of the death of the mystic poet Jalal al-Din Rumi—whose teachings formed the basis of the Mevlevi order of dervishes—and of the centennial of modern-day Turkey.

“Two Nightingales in a Rose Bush,” Double-Sided Illustrated Leaf from an Ottoman Album by 'Abdullah Bukhari (active ca. 1725–50s). Turkey, probably Istanbul, Ottoman period (1299–1923), ca. 1725–45. Opaque watercolor with black ink, shell, and gold leaf on paper, with a marbled paper margin; Folio: Height 16 5/16 in. (41.4 cm), Width 11 in. (27.9 cm). Purchase, Ravi and Seran Trehan Gift, in celebration of Turkey’s Centennial, 2023 (2023.217)

Turkish Centennial Initiative in the Department of Islamic Art

In addition to the special installation Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past, The Turkish Centennial Gala was held on October 25, 2023. Proceeds of over $2 million from the event went to the Museum's Turkish Centennial Fund. The fund was established in 2019 to underwrite Turkish art initiatives within the Museum’s Department of Islamic Art, including acquisitions, exhibitions, research, and a lecture series (see presentations by distinguished scholars such as Nurhan Atasoy, Walter Denny, and Nebahat Avcioğlu). Exclusive items of home decor and clothing are sold in The Met Store, for more information see here and here.